Following the “Red Summer” of 1919, rampaging whites killed hundreds and perhaps thousands of African Americans in pogroms and race riots. One of the most frightening, murderous events occurred in the Mississippi Delta country in and around Elaine, Arkansas. Late on the night of September 30, one hundred years ago, at a church located at a country cross-roads called Hoop Spur, about 100 African Americans met to organize the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America, a union of land owners, tenants, and sharecroppers. Blacks far outnumbered whites in Phillips County, but whites had most of the guns. A carload of whites with guns approached the meeting and exchanged fire with black people guarding the church. One white man was killed and another wounded, possibly by stray bullets from their own side.

What happened next highlighted the racial holocausts sweeping the United States in the wake of World War I. Hundreds of white vigilantes from Arkansas and Mississippi, dozens of law enforcement officials, and most deadly of all, 500 U.S. soldiers mobilized from nearby Camp Pike by the Arkansas governor, led hellish assaults for the next four days. According to eye witnesses and proud accounts by those who did it, mobs went from house to house killing black occupants. Troops marched through forests where people went to hide and used machine guns to mow down every black person in sight. One modest estimate counts 100 to 237 dead, but other accounts suggest that hundreds more black people died. We will never know how many bodies clogged the rivers and were covered over in the woods.

Why did this happen? The causes and legacy of that event were national. In 1919, the United States was in the grip of a racist, anti-labor and anti-communist fervor. The Russian Revolution, the Seattle General Strike, and union unrest set off a massive propaganda campaign by the media and government against the left, unions, immigrants, Latinos and African Americans, Mass deportation of immigrants, shootings, and arrests followed. But racism lent a special viciousness and violence to the Red Summer, weaponizing white workers and white ethnics to attack black neighborhoods and black workers, some of them brought in by employers to break strikes. In 1919, employers played off workers against each other to kill a national strike of 350,000 Steel Workers, destroy interracial packinghouse worker organizing in Chicago, and undermine unions everywhere.

The high point of violence followed in Elaine, based on the South’s legacy of slavery and institutional violence against black people. A white landowning class in the Arkansas Delta had once made millions based on slave labor. Supported by whites from other social classes, they crushed black freedom after the Civil War through lynching, disfranchisement and segregation. In 1919, the price of cotton had shot sky high, and white landlords, merchants, and cotton factors stood to gain a windfall profit if they could keep the black workers who planted, tended, and harvested the cotton from getting a fair price for their crops. On the eve of cotton harvest, black unionists meeting at the Hoop Spur church demanded higher prices for their cotton from local white elites or pledged to go around them entirely by taking their cotton to market somewhere else. Pure greed set the landed gentry against them. White authorities claimed black unionists were organizing an “insurrection” and mass killing of white people, rather than getting an equitable price for their crops. Their unionization drove the planters wild.

In this awful time, black armed self-defense set a new level of resistance during and after the Red Summer. In Elaine as elsewhere, black soldiers returning from World War I had weapons and knew how to use them. “New Negro” racial uplift and organizing included the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Universal Negro Improvement Association led by Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, both of which had branches in Arkansas. The black press, particularly the Chicago Defender, connected their resistance movements and the war had set off the huge Great Migration of black workers to work in industry in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and elsewhere. African Americans struggled for a way out of Jim Crow poverty, sometimes joined unions, and fought fiercely against racist attacks.

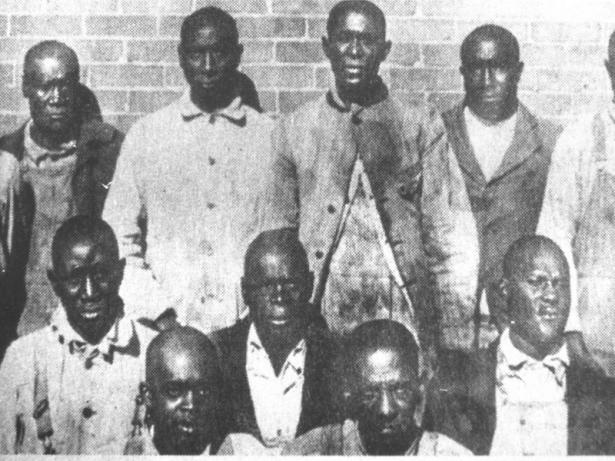

Yet the mass shooting in Elaine Massacre highlighted the ferocity and cruelty of racism and revealed the perversion of the criminal justice system. After the shooting ended, the justice system indicted no white murderers. Instead, authorities held nearly 300 African Americans in a jail in Helena designed to hold forty-eight and used torture and beatings to elicit “confessions.” Union leader Robert Hill escaped the state, but a Phillips County grand jury indicted 122 black people. In two separate trials, all-white juries took only minutes to convict twelve union members and sentence them to die in the electric chair. Following the orgy of violence in 1919 came the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan as a mass movement and its political takeover in parts of the lower Midwest and the South in the 1920s. Racial violence didn’t stop. In 1921, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, mobs of whites raped, murdered, looted, engaged in mass shootings, and bombed from the air to destroy the thriving black community of Greenwood. Again, dozens or hundreds died, and whites burned the business district and some 200 homes to the ground.

Elaine left a few kernels of hope and seeds of organizing for the future. Black writer and organizer Ida B. Wells-Barnett, black Arkansas attorney Scipio Jones, and the NAACP saved the Elaine Twelve from the electric chair. By 1925, they were all released from prison (and spirited quickly out of the state), and their case before the U.S. Supreme Court (Moore V. Dempsey, 1923) strengthened the court’s interpretation of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to correct state criminal trials that blatantly ignored the rights of defendants. The ghosts of Elaine unionists also reached out to the next generation when the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union organized in the Arkansas Delta again in the 1930s. Racial terrorism and cotton mechanization destroyed the STFU but civil rights organizers in the 1960s chose to remember that blacks and whites in Ku Klux Klan country for a time successfully organized this bi-racial union.

But unfortunately, there is no closure on racism. There should be federal and state investigations to clarify what happened in Elaine so that the next generation does not continue to believe the myths created by those who carried out the murders, and to consider ways to repair the economic damage. When the Elaine Legacy Center remembered the town’s martyrs by planting a tree last August, someone cut the tree down. In a town of 500 or so people, about forty percent of them African Americans, median household income hovers between $16,000 and $19,000, and some forty percent live in poverty. Racial terror (and later, farm mechanization) undercut the fortunes of generations of black farmers.

It remains extremely important that we remember, but also how we remember it. The great sociologist W.E.B. DuBois later explained that racial separation and violence drove a stake through the heart of nascent labor movement in the South, destroying the potential of union incomes for white as well as black workers. Elaine remains a fully American story that must be told. Elaine was a turning point, but it was only one of many.

We need to honor those who gave their lives. Their struggles leave a trace in history that can be picked up, learned from, and built upon. We also need to remember the past in order to do something about its legacies. That is our challenge today, as we fight anew against white supremacy and mass shooting terrorism. The evil of the “red summer” of 1919 still haunts the land. Evil’s still on the loose, and you’ve got to take a side.

Michael Honey’s most recent book is To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice. Among other books, he also wrote Sharecroppers’ Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition, with a Forward by Pete Seeger.

Spread the word