books The Historical Retrieval and Controversy of Walter Rodney’s Russian Revolution

The posthumous publication of Walter Rodney’s book on the historiography of the Russian Revolution is a remarkable accomplishment of historical retrieval, and it provides us with an opportunity to look more deeply into Rodney’s relationship to Marxism, Soviet Communism, and Maoism and post-colonial politics.

The editors have collected surviving texts from lectures given at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania in 1970-1971 that restore the voice of the Pan African historian best known as the author of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, who was martyred in the struggle for people’s power and an end to dictatorship in Forbes Burnham’s Guyana. This volume clarifies the legacies of Rodney (1942-1980), whose legend is based on a few books perennially in print that are imbued with the personality of a charismatic teacher.

This book deserves a wide readership precisely because it will stir intellectual and political controversy. Does Rodney articulate an African or Third World view that relates revolutionary theory and history to people in motion? Does he transcend the ideological fault lines of the Cold War? Does the author clarify the postcolonial legacy of the Bolsheviks? Is the historiography of the Russian Revolution, a world-shattering event, best read through the framework of the “long Russian Revolution”? However much the editors wish to present Rodney as a “nonsectarian,” this is obviously an ideological and highly polemical project. While this can make for an exciting read and can engender debate, it cannot satisfy everyone who engages such a partisan topic. And revolution is never a neutral or superficial subject.

Bourgeois and Marxist World Views

Though it is good to be aware of Cold War anti-communist prejudice regarding this history, there are by no means, as Rodney begins his discussion by stating, only “two world views” of the Russian Revolution, “the bourgeois” and “the Marxist.” There are many schools of socialist thought, not a few of which, while offering criticism, defend the accumulation of capital and justify hierarchy and domination as progressive on certain terms. Rodney appears to argue that every imperial every imperial government-sponsored scholar, or every scholar sympathetic to Western capitalism during the Cold War, was incapable of producing research that illuminated revolutionary events. While this may be a good first principle for critical thinking, and reminds us validly that scholars who claim an objectivity beyond politics are dubious, this proposition is not entirely true where the historian’s craft is concerned. Rodney does add nuance to and complicates these initial premises, but his comparative method is deficient where he divides the historiography largely between Western imperialists (and a few dissenters) and “Soviet” scholarship, by which he means those Russian thinkers who view this history through either the lens of state planning or that of one or another version of nationalism.

Rodney’s standard of a legitimate Western imperial-sponsored scholar is E.H. Carr. Carr was both a diplomat for the British empire and a prolific historian of Russia. He was skeptical of Marx’s legacy, but scholars argue whether Carr was informally a socialist. Largely sympathetic to the Bolsheviks in the name of pragmatic foreign relations, Carr disagreed with viewpoints that insisted the Soviet economy had failed. However, it is difficult to say how Rodney may have received Carr’s own posthumously published works.2

Carr, in his analyses of the Third International’s relations with insurgent movements abroad and the regimes that repressed them, challenged the Soviet Union’s official self-image. As I will subsequently illustrate, despite historians being on the other side of the Cold War from Russia, this did not preclude occasional genuine documenting of some inconvenient truths that should inform ethical engagement, especially where these claims mirrored the experience and conclusions of dissident and grassroots radicals.

Rodney’s presentation overwhelmingly assumes that Bolshevism is a coherent body of revolutionary thought and that the Bolshevik seizure of state power was the primary epic event of, and is synonymous with, the Russian Revolution. While the manuscript suggests an “African” or “Third World” viewpoint, little of Rodney’s survey clarifies what this means. In the conclusion of the manuscript, there is a suggestion that peoples of African and peripheral nations need to decide how they view these seminal historical events and that Russia may be a model of peripheral national development.

Rodney’s treatment of “Marx, Marxism, and the Russian Left” surveys debates about how Marx saw Russia as a peripheral peasant society, whether Marx showed the peasantry contempt, and whether he believed revolution was possible in Russia. Rodney ambivalently engages with Engels’ view that the formation of a Russian bourgeoisie was necessary before socialism was possible. He also engages with different intellectual currents in the national history of Russia, as represented by Nicolas Berdyaev’s scholarship, from opposition to the state to whether Westernization of Russia was progressive.

A concise survey of the ideas of Marx, Bakunin and Nechaev, the Narodniks, Kautsky, Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and Luxemburg are subordinated to Rodney’s focus: his admiration for the building of a socialist state and his sympathy for the government that navigated a nation-state and national economic development through an imperialist world system.

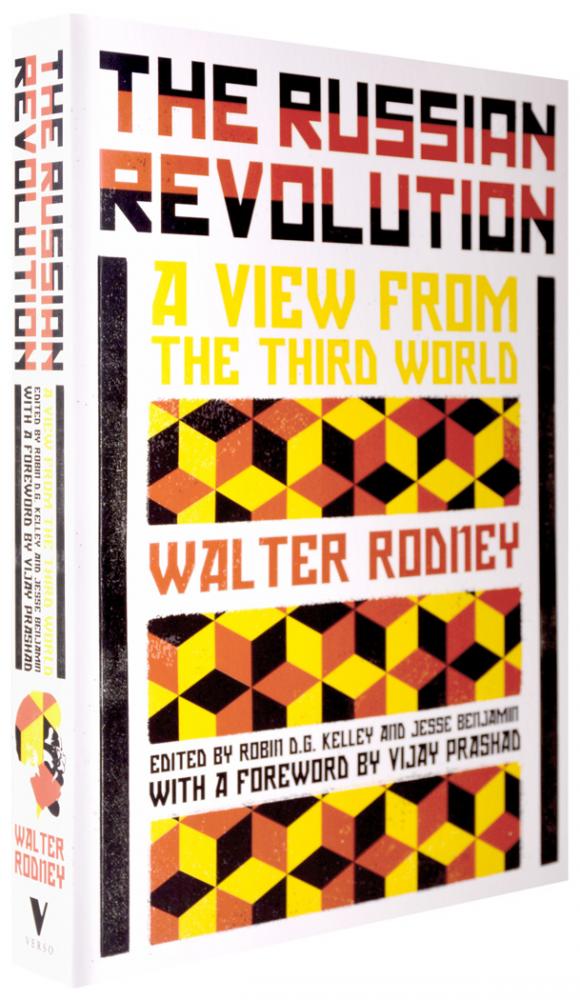

The Russian Revolution:A View from the Third World

By Walter Rodney

Edited by Jesse Benjamin and Robin D.G. Kelley;

Foreword by Vijay Prashad

Verso; 336 pages

July 10, 2018

Paperback.with free ebook: $18.86

ISBN: 9781786635303

Rodney, given the antipathy for the Trotskyist heritage he expresses elsewhere, is surprisingly delighted with Trotsky’s A History of the Russian Revolution. He affirms Trotsky as a historical actor, his articulation of the class struggle and the refined manner in which he wielded historical materialism as a tool. Strikingly, Rodney underscores the fact that Trotsky writes not about modes of production, a topic that sometimes weighs down Rodney’s own writings, but the social motion of ordinary people. This “Third World viewpoint” particularly makes note of Trotsky’s theory of combined and uneven development, how the proletariat and the peasantry struggle under specific historical conditions, and that a new society can nevertheless emerge from the burden of minimal industrialization or incomplete modernity.

Where Are the Soviets?

Rodney’s discussion of democracy, Bolshevism, and the early years of the Russian Revolution before Lenin’s death is hampered by his uncritical reception of dogma that defends the Bolsheviks’ retention of state power as the revolution itself. The idea that the Bolshevik state under Lenin was an extremely repressive force, or even a counter-revolutionary force, is neither unscientific nor Western propaganda. Whatever the motivations of Cold War-era historians R.V. Daniels and Leonard Schapiro, who underscored the rise of an autocracy before 1923 and the rejection or reversal of any commitment to direct democracy and workers’ self-management under the early Bolsheviks, this same perspective was held consistently in different variants by anarchist, left libertarian, left communist, and autonomous Marxist historians and by committed radicals. Rodney appears to know nothing about such perspectives other than they must be myths invented by imperialists. A severe omission in Rodney’s survey is the absence of the soviets “with a small s”—that is, the workers, peasants, and soldiers councils—which represented forms of popular self-mobilization and self-government. Nowhere are they discussed as independent political forms of freedom. Instead, predictable glosses are offered on the Constituent Assembly, the Bolsheviks’ rise to power, and the intrigues of the subsequent “civil war,” an account which doesn’t credibly distinguish external threats of empire from domestic counter-revolutionaries, real and imagined.

Civil war in the midst of a social revolution is a real thing—what does class struggle ultimately mean without one? It certainly doesn’t mean only free or low-cost health care, public housing, and public schools plus a new trend toward industry and infrastructure. As the Spanish Civil War made clear, there can be many left and right factions in conflict, both before and after some force takes and holds state power above society.

Rodney, it is worth underscoring, notes that most of the Bolsheviks, except Trotsky, were in exile during the actual insurgent events, though Trotsky participated in the Petrograd Soviet and thought in some indirect way that the soviet was the basis of the new state and that Lenin was less impressed with the nature of this institution of popular self-government.

Rodney suggests that our understanding of anti-imperialism is crucial, and that Lenin’s Imperialism is essential, for understanding the political economy of empire. Is it crucial for understanding how to oppose the empire of capital or how peripheral rulers can maneuver to accumulate national or state capital? These are not the same but are often confused. In his Imperialism essay, Lenin notably said that the financiers once had a progressive purpose (on certain terms it can be imagined that finance capital can be reformed and disciplined to do so again). Lenin’s Imperialism underscores the importance of industrialization without advocacy of workers’ control or rejection of wage labor. These matters tend to be forgotten when considering Lenin’s views on the aristocracy of labor and global division of capital. Rodney does not seem aware of the Lenin of the Zimmerwald Left, who said socialists should “turn imperialist war into civil war.” While Lenin famously said, “All power to the soviets” (inspiration for the Black Panthers’ “All Power to the People”), once he took and held state power, he said that believing that workers could govern themselves was like believing in fairy tales.

The alert reader can see, and the editors note, that Rodney in his reading of the Russian Revolution teaches that at a certain point independent labor action is a threat to “the long revolution,” or national economic development. Consequently, workers’ self-activity and protest can be validly termed sedition and can be met with violence. Critical thinkers should be placing that view in conversation with the experience of the insurgent activist Rodney, who met repression in Jamaica in 1968 and Guyana in 1980.

The Long Revolution

“The long revolution” is a framework that argues the Global South has gone through successive awakenings. According to this theory, peripheral and underdeveloped societies are trying to catch up to the imperial powers in economic equality and development. The Western bourgeoisie accumulated capital over hundreds of years to have their nation-states become centers of power. Aspiring ethical bourgeois elements of the Global South are trying to compete with the Western imperialists and are seen as the allies of the proletariat and peasantry. It is argued that the long road to socialism has hardly begun because class formation in the periphery has hardly begun. There is a belief that states want independence, nations want liberation, and peoples want revolution. But this conflates modernization and development with class struggle, and subordinates the latter to the former. It also argues that capital accumulators can be liberators.

The long revolution is a Stalinist and Maoist interpretation of the meaning of the Russian Revolution and has had its African advocates, such as A.M. Babu and Samir Amin. Amin, not long before his recent death, argued that contemporary Russia and China—where there is no longer any pretense of being a worker-centered or socialist society—are part of this long development. But Trotsky himself created a historical problem by his theory of the “degenerated workers’ state,” where the police state was a defender of “proletarian gains”—nationalized and public property.

Trotsky first used the term “degenerated workers’ state” to describe Soviet Russia in the mid-1930s. By it he meant a state that had nationalized property but where, under Stalin, the Communist Party bureaucracy had displaced the workers, who no longer held power directly. Trotsky believed that Stalin’s party had become a bureaucratic caste that defended state property but inhibited workers’ power, and that it might capitulate to capitalist tendencies from within and from without. Though both had a role in suppressing the soviets, Trotsky of course believed that the Bolsheviks holding state power, under Lenin’s, and earlier his, leadership, had meant that workers held power. For him, Bolshevik power and workers’ power were synonymous.

So then is Rodney correct that a certain type of capitalist development, in the Marxist-Leninist view, can contribute to the socialist transition?

The editors have located much of the logic of this Rodney manuscript in the framework of the long revolution. I believe they are correct; this is overwhelmingly how Rodney saw Russia in 1970-1971. Further, the meaning of a Third World viewpoint on Russia here is consistent with the loyal-opposition criticism of Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa socialist Tanzania that was present in university life there in the 1970s.

Much has been made of the golden age of the Dar es Salaam campus in this period, where Walter Rodney, John Saul, Dan Nabudere, Yoweri Museveni, Karim Hirji, Mahmood Mamdani, and Issa Shivji were all present and where Robert F. Williams, Stokely Carmichael, and C.L.R. James visited. The “Dar es Salaam school” analyses really had two souls: endless debates about modes of production and class formation that assumed materially social revolution from below was impossible and a growing awareness of what were in fact independent labor actions of workers and farmers against the Ujamaa socialist state.

Rodney’s Russia Revolution lectures were prepared for this intellectual environment. Perhaps dual power and insurgent situations were discussed more informally. By 1975, Rodney’s essay “Class Contradictions in Tanzania” revealed that there were in fact independent labor revolts against the state planners in that country. Issa Shivji’s Class Struggles in Tanzania (1976) records these. Yet in 1970-1971, according to this volume, Rodney sees the comparative discussion of Russia and Tanzania in terms of the way that peasants are being drawn into the money economy, and the manner in which motor boats and refrigeration are being introduced, as “a quiet revolution.”

Rodney’s chapter on how Russia transformed its empire reveals something present in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa: a lack of proper respect for African and peasant cosmologies. A recent, insightful essay by Guyana’s Kimani Nehusi, while sustaining Rodney as still a paramount scholar of Africa, notes this limitation.4 Rodney sustains uncritically a historian, Georges Jorre, who speaks of tribes who worship bears and trees in the Siberian forest and hunter-gatherers, pastoralists, and nomads who only know a thousand and one ways of starving to death. There is an implication of backwardness that needs to be overcome. Rodney, who had the capacity for an insightful ecological perspective before this was fashionable, did not reveal such here.

Rodney argues the study of nationalism in Russia is primarily a field of bourgeois scholarship and is hostile to the Bolsheviks. It is Rodney’s general view that Russian scholars try to emphasize national unity. Yet, he soon reveals nuance beyond this initial bifurcation.

National Liberation Struggles Within the Soviet Union

From the tsar’s time to Stalin’s rule, Rodney understands that there was a persistent Great Russian nationalism that was racist, that non-Russian peoples of the Soviet Union had a critique of Great Russia for its plunder and exploitation. After the Russian Revolution, Lenin did not fulfill his promise of self-determination. National liberation within the Soviet Union was defined in restricted terms. The Bolshevik state was nationalist, in fact, while projecting internationalism abroad. Just because Richard Pipes is a conservative Western historian doesn’t mean his early study of oppressed peoples’ search for autonomy is made up out of thin air. Rodney shows awareness that no matter the level of struggles between social classes among peasants, radical peasants were far more attracted to the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the party that was heir to the Narodnik tradition, than they were to the Bolsheviks. As Rodney suggests, anti-colonial nationalism in its search for autonomy can be bent to class struggle or to race-first capitalist perspectives, so one must be alert to opportunism on all sides.

Rodney’s discussion of the building of the socialist state in Russia is undeniably a discourse on the search for, accumulation of, and defense of national capital, with no suggestion that relations between capital and wage labor are inherently oppressive. Rodney’s is undoubtedly a certain type of Marxism—I say this without the need to defend the integrity of something holistic called “Marxism.” However, there is no human action in this discourse except what elite state planners are thinking.

Where Rodney surveys Soviet Russian authors, he never inquires about how the socialist project was transformed into a nationalist and capitalist one, nor does he ask when this happened. There is no sense that Russian authors might be writing history and discussing political economy on behalf of the state that suppresses workers’ self-emancipation. Rodney fails to recognize that just as one criticizes Western Cold War historians of Russia, so too must one be critical of Soviet historians or political economists (Rodney cites both) where they increasingly substitute details of the nation’s gross national product for the meaning of socialism.

While an ambiguous process of transformation is going on, Rodney does find it dubious that at any point in the long revolution has a socialist or communist society been established once and for all, not in 1917, 1937, or even by 1971. Yet Rodney sees state planning, as he indicates in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, as the political economy of Russia, Eastern Europe, China, and North Korea, leading to the conclusion that these are progressive societies. This is where the failure to take seriously socialism as a toilers’ democracy (direct majority rule) can lead.

Rodney viewed the Soviet Union as an affirmative-action empire. He was working with a definition of socialism and communism as the equal distribution of goods and perhaps diversity in the hierarchy of the public service. This is what he was observing and measuring in the long revolution, not the self-mobilization of working people.

The long-revolution framework assumes the popular will died or became irrelevant somewhere between 1917 and 1921 and that there were no valid expressions of the popular will outside the Bolsheviks once they seized state power. Rodney notes that Stalin abolished Lenin’s workers’ and peasants’ inspection without regard for the fact that Lenin’s state smashed all workers councils not loyal to the state and Lenin bragged that he brought civil war to the peasantry, calling many enemies of the people. Rodney also criticizes the Mensheviks, consistent with Lenin’s opinion, for advocating a long view of state capitalist development as the meaning of socialism, even though Rodney, like most Marxist-Leninists, proposes ultimately the same thing.

While condemning the Moscow trials and Stalin’s violent repression, Rodney was rightly concerned by scholarship that discredited the socialist experiment by emphasizing psychopathic personality theories comparing Stalin to Hitler and by writers who were less than rigorous in suggesting that communism and fascism might be similar projects. Communism, at its best, is premised on social equality and workers’ democracy; fascism is marked by racism, patriarchy, imperial ambition, and the reorganization of capital for national purpose. Still, they can be similar projects where they seek to discipline capital (not abolish it) and repress independent labor action.

Walter Rodney and C.L.R. James

The editors take note of the curious silence of Rodney’s Russia manuscript on the historical ideas and political economy of C.L.R. James’s writings on the Russian Revolution, Eastern Europe, and workers’ self-emancipation, though the editors maintain the historical legend that Rodney was among the few Caribbean students who stood up to and challenged James in their famous London study group of 1964-1965. The fact that this has not been the subject of a symposium makes us wonder what is known and what some fear will be discovered. These types of silences make a mockery out of the framework of the Black radical tradition. We should not be creating “Mount Rushmores” to decorate the university, but allowing representative thinkers to reveal radical debate and disagreement, facilitating deeper political thinking.

Both the editorial introduction and the foreword, when read carefully, suggest contradictory ideas about James and Rodney. The two share a Black radical tradition with ambiguous content. James informed (and did not inform) Rodney; James may have influenced and may have been profoundly dissatisfied with Rodney’s historiographical survey. While this is not a review of James’s ideas, these conflicting tendencies and silences compel a concise response.

Rodney did not identify with James’s views on direct democracy and workers’ self-management as articulated in historical case studies of Classical Athens, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and in James’s discussion of the soviets (popular councils) in Modern Politics. Rodney viewed Stalinist Russia and Eastern Europe as progressive for their modern political economies or aspirations to such—this meant supporting, as did Mao Zedong, the suppression of the Hungarian workers by Stalinist Russia. Uncritical affinity for Maoism was a major staple of the East African left in this era, and Rodney’s Russia manuscript is peppered with references to Mao that do not enhance its scholarly presentation or political insight.

Rodney believed state capitalism (or if you wish state socialism) broke up the former political economy of the colonizer. James thought FDR’s New Deal, Mussolini’s and Hitler’s fascism, Stalinist Russia, Fabian Britain, early Maoist China, and Tito’s Yugoslavia were all state capitalist. Though he recognized these as variations on the one-party state and welfare state (which are not the same), James felt they were similar in being militantly hostile to independent labor action and seeking economic development, with their welfare state of mind, at the expense of labor’s hides. He believed that supposed colonial independence cannot be guaranteed, and statesmen who posture that they have secured it, and brag about the capital they are accumulating and defending in the world system, only have power as administrators over their country’s toilers’ lives.

James’s World Revolution, which Rodney does not discuss, argues Stalinism is not merely what happens in Russia under Stalin. It is the practice of collaborating with the left bloc of capital by Communist parties all over the world. Rodney, having observed and perhaps been influenced by the intellectual legacies of the Moscow-oriented Cheddi Jagan in Guyana, a major leader of his native land’s movement for colonial freedom and a shaper of its intellectual history, should have taken this more seriously. Yet Rodney argues there are times, following Stalin and Mao, when it is valid for radicals to collaborate with the left bloc of national capital and this can be termed “a democratic front.”

Rodney (like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin) agreed that nationalized property was a gain for ordinary people that could be maintained by a police state. James came to believe, while preserving the memory of Lenin as a peculiar left libertarian thinker who repressed the soviets, that nationalized property was not a step to a future socialist society that would be distinguished by freedom unless toilers invaded, occupied, and controlled it. Nevertheless, the editors may have the right inclination, though the wrong historical assessment, when they suggest that James would have seen the Bolsheviks from a more radical democratic critical lens than Rodney.

If James passed on to Rodney anything that he included in this manuscript, it may have been the former’s appreciation for Trotsky as historian and historical actor in the Russian Revolution. James also agreed with Rodney that the crimes of Stalin, or of any authoritarian ruler in another global location, cannot permit the delegitimation of historical experiments that search for working-class self-government. Still, James investigated the similarity of diverse capitalist forms across the globe for their authoritarian ways. Rodney decided the United States was the greatest purveyor of violence in the world and peripheral capitalist nation-states or blocs of capital were socialist projects (even where labor was suppressed and democracy was not present) if their rulers were trying to delink from empire.

In Rodney’s chapter “On the Inevitability of Socialism,” where he explores this Marxist theory, he sees it as an argument about modes of production that must change for social change to happen. Take for example, the transition from feudalism to capitalism, then from capitalism to socialism. James saw what was inevitable quite differently. It was inevitable that working people would confront institutionalized oppression and obstacles they placed in their own path and that if they did not succeed in establishing the process of a self-directed socialist future they would be subjected to barbarism. This principle was true no matter how capital was organized at any one time.

James did think capital had an inevitable tendency to organize working people to build a successor society within the shell of the old. The emergence of a free or new society was not inevitable, though being subjected to oppression was perennial and looking for a new society in embryo was a plausible manner to analyze society. Rodney stopped looking for this in Russia after 1921, as did many sympathetic to Bolshevism and Leninism. This has implications for how aspiring radicals analyze all global spheres.

While Rodney, by 1970-1971, had more precise knowledge of precolonial African cultures than James, James too could speak of the African peasantry in the 1970s as very self-reliant but starving, and at a disadvantage for their insufficient access to capital. Both of them had to rethink the forced collectivization of peasant farmers in Africa (Tanzania), the Caribbean (in the Haitian Revolution), and Russia. Rodney seems aware that the enclosure of the commons in feudal Europe was abusive, but he thinks that under Stalinist Russia it was not so harsh.

Anti-imperialism and Peaceful Coexistence?

The Russian Revolution, despite all its issues and complexities, continues to be a world historical event because it is an archive of questions about how social revolutions emerge and set the terms of the future socialist society. It is not nonsectarian, but dogmatic, to suggest there is one “African” or “Third World” view of these events, nor does such a point of view represent a rupture with the Cold War mentality. The differences between Rodney and James make it clear there is no singular “Back radical” perspective or ethic, and such an assertion can be a cheap marketing ploy when intellectual and political history make it clear that socialism and anti-imperialism can be understood in various ways.

The Cold War wasn’t imposed solely by the United States. The Stalinist notion of “peaceful coexistence” with the United States during the Cold War, under the premise that they would compete successfully to see who could manage national growth better, obscured the fact that there was no long revolution. Where contemporaries talk about peace and anti-imperialism together, this is worthy of a few raised eyebrows.

At this historical moment, when it is becoming clear that most critiques of neoliberalism are pro-capitalist, one can see that public and nationalized property may return by some means once again into vogue. It is up to radical thinkers to clarify that such property forms are not necessarily “progressive” but can be used to sustain the profit system and to thwart labor’s self-emancipation. Despite the way in which empire creates unequal divisions of labor and capital, the issue is the same all over the world. We should be observing not redistribution of capital among elites or by hierarchical government, but the power for ordinary people to directly govern. Redistribution of wealth is one function of toilers governing; they can also carry out judicial affairs and foreign relations and preside over ecology, health, housing, education, and all cultural matters.

The heritage of the Russian Revolution compels us to ask, will we identify with a police state as the defender of the poor and powerless, or will we reframe revolution as a process of ordinary people arriving on their own authority, even where so-called progressives come to power above society?

A Third World point of view is not best understood as underscoring solely that the United States is the greatest purveyor of violence across the globe. It can mistakenly give an identity politics valuation to peripheral political economies and their elite planners. It can offer to misleaders of color who aspire to capital accumulation a false banner of fighting for social equality. It can erase the search for direct democracy and workers’ self-management by terming authoritarian nation-states “peoples,” as was common in the era of the Bandung and Tricontinental conferences and which stems from the heritage of Stalinist Russia. A Third World viewpoint can obscure a commitment to an underdevelopment discourse that argues ordinary people can’t govern without being exposed to the proper amounts of technology, industry, and modernization.

Despite the shadow of the historical context and ideological disposition that Walter Rodney was writing under in the early 1970s, his The Russian Revolution will be valuable to thinkers who have been observing that the critique of neoliberalism is not necessarily a rejection of capitalism and may itself represent a certain type of capitalist alternative, even though “socialist” chatter is heard. Discourses pushing toward a next system, or beyond capitalism as we know it, have something in common with the Cold War political economies of the past. They may diagnose what ruling classes are debating or aspire to but may not tell us where to look for the new society and how to bring it closer.

Rodney’s The Russian Revolution, in my view, is not the best book for an introduction to the events or the issues that surround them, though it tells us a lot about the Third World national liberation epoch and its blind spots in the 1970s. Still, Rodney’s historiography of the Russian Revolution can be fruitfully placed in conversation with C.L.R. James’s lectures on the historiography of the French and Haitian revolutions and Murray Bookchin’s Third Revolution, which includes historiographies of both the French and Russian revolutions. As evidence that clarifies how Rodney actually saw socialist history and theory, it will have staying power and will contribute to creative conflict in how historical revolutions are understood.

Notes

1. Walter Rodney, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World (Verso, 2018). Edited and introduced by R.D.G. Kelley and J. Benjamin. Foreword by V. Prashad.

2. E.H. Carr (1892-1982) died two years after Rodney was assassinated. His posthumous works included Twilight of the Comintern, 1930-1935 and The Comintern and the Spanish Civil War. These show through documented research the Soviet Union’s conscious promotion of alliances with bourgeois, nationalist, and capitalist forces against insurgent international socialists and anarchists. Between 1930 and 1939 the Soviet Union went from propagating the idea that liberals and social democrats were “social fascists” to reversing this view circa 1935, redefining radicalism and democracy toward collaboration with these same forces to repress genuine revolutionaries. This is where the contemporary idea of “progressive” surfaced. The former “social fascists,” for example Franklin Roosevelt, were now “progressive.” And progressives and Stalinists created a “democratic front,” later to be called a “popular front.” This led to a silencing of the racist and imperialist implications of World War II as embodied by both the Allies and Axis powers. Before the United States entered World War II in 1941, in between the democratic front and the popular front, there was the Hitler-Stalin pact (1939-1941) that further distorted how Moscow-oriented Communist Internationalism was received.

3. Authors include Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, G.P. Maximoff, Voline, Peter Arshinov, Victor Serge, Boris Souvarine, Karl Korsch, Paul Mattick, Herman Gorter, Anton Pannekoek, Maurice Brinton, Paul Avrich, Oskar Anweiler, and Murray Bookchin.

4. Kimani Nehusi, “Forty-seven Years After: Understanding and Updating Walter Rodney,” Africa Update (26.3, Summer 2019).

[Essayist Matthew Quest teaches World History and Africana Studies at University of Arkansas at Little Rock. See his essay on C.L.R. James and the Haitian Revolution in The Black Jacobins Reader.]

New Politics is an independent socialist journal that describes itself as " help(ing) provide informative, timely analysis unswerving in its commitment to struggles for peace, freedom, equality, and justice — what New Politics has called “socialism” for a half-century." For information on subscribing or donating to the magazine, go HERE.

Spread the word