The New York Times’ obituary of Larry Kramer (5/27/20) announces in its lead that Kramer “helped shift national health policy in the 1980s and ’90s,” but the rest of the obituary doesn’t explain this absolutely justified introduction.

FAIR

To read it, you would think Kramer was a moderately successful writer and an ill-tempered activist. Though both Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and the AIDS Coaltion To Unleash Power (ACT UP) are mentioned briefly, you would have no idea that they are two of the most important public health organizations of the 20th century, and the most important public health organizations for LGBTQ+ people in the last two decades of the century.

If you sift through the swipes at Kramer (“raucous, antagonistic,” “enjoyed provocation for its own sake”; an early edition called him “often abusive”), you find a striking acknowledgement of Kramer’s role in the development of HIV treatment and the reform of FDA processes: “essential” in the opinion of none other than Dr. Anthony Fauci. It’s striking, because Fauci was the target of so much of ACT UP and Kramer’s rage during the early AIDS crisis. “Even” officials (like Fauci) whom Kramer condemned at the time, says the Times, recognized that Kramer was sounding the alarm on a public-health emergency. Yet these attestations to his accomplishments feel like asides in the piece.

Nowhere in this obituary is there any comprehension of the horror of those years—the constant death, the fear, the tremendous courage, the anger. Identified initially as a “gay disease,” the onset of AIDS in the early ’80s further stigmatized queer people; gay men were shunned, evicted, disowned, fired and dying by the thousands. Infection and stigma spread to other marginalized communities, particularly communities of color. With no funding, no research, and not even government acknowledgement of the crisis, entire populations were essentially left to die in a modern plague. Trauma and terror shaped an entire generation of queer people, and those of us who survived feel the devastating losses to this day.

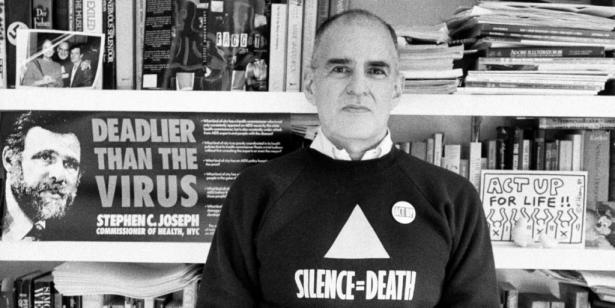

Into this nightmare, Larry Kramer threw his whole self with equal parts desperation and determination, fueled by righteous rage. Movements are never made by one person, but he played an outsized role in that generation’s fight for our lives. In the 1980s—the worst years of the AIDS crisis—Kramer was a founder of GMHC, which provided everything from crisis counseling to legal aid at a time when HIV+ people were treated like modern-day lepers; a founder of ACT UP, which changed both US healthcare and activism forever; and the author of The Normal Heart, a gut-wrenching play about the times that went on to win a Tony in 2011 for Best Revival of a Play.

FAIR

These achievements would be remarkable under any circumstances, but in the midst of a plague, they were truly extraordinary. ACT UP in particular played an enormous role in the course of the AIDS pandemic: It combined research, direct action, education and lobbying, and without it, untold thousands more would have died.

Yet GMHC gets four lines of mention in this obituary, and ACT UP five. By contrast, Kramer’s less successful literary ventures get a total of 57 lines. (The Normal Heart gets 13.) Moreover, ACT UP is summed up pejoratively: its

street actions demanding a speedup in AIDS drugs research and an end to discrimination against gay men and lesbians severely disrupted the operations of government offices, Wall Street and the Roman Catholic hierarchy.

The Times doesn’t mention that those disruptions were ultimately largely successful.

The most unfair—and the most revealing—line in the obituary, though, is the one about enjoying provocation for its own sake. In context:

Mr. Kramer enjoyed provocation for its own sake — he once introduced Mayor Edward I. Koch of New York to his pet wheaten terrier as the man who was “killing Daddy’s friends” — and this could sometimes overshadow his achievements as an author and social activist.

The encounter with Koch related here is anything but “provocation for its own sake.” It’s a speaking-truth-to-power moment in which Kramer confronted an official whose decisions did indeed have life-or-death consequences for New Yorkers at risk for AIDS, and who deserves shared blame for the city’s death toll because of those decisions.

The Times’ failure to recognize the Koch anecdote as a deliberate political act goes to the heart of the underlying problem with this obituary—and it’s the problem with much of the New York Times’ coverage of social movements. To acknowledge the role that Kramer and ACT UP played in US politics is to admit that direct action, civil disobedience and other disruptive strategies of power from below work. Which is to say, the Times has it exactly backwards: Kramer’s confrontational approach didn’t “overshadow his achievements,” they are what made his achievements possible.

This truth could hardly be more relevant right now. Jeff Bezos is making headlines as the world’s potential first trillionaire, while he cuts hazard pay for Amazon workers. Trump forces immigrant workers back to unsafe meatpacking plants, while speeding up the deportation of children. Governors are “reopening” despite expert warnings, while BIPOC communities suffer and die disproportionately. Tens of millions face housing and food crises, while corporations walk away with the relief funds meant for small businesses. And police are savaging anti–police violence protesters from coast to coast, while Trump cheers from the only place in America that has consistent testing and contact tracing.

If ever there was a time to act up, be confrontational, disrupt and demand an end to this dystopia, it is now. Larry Kramer was right: “If you write a calm letter and fax it to nobody, it sinks like a brick in the Hudson.” Let’s honor his legacy and raise hell.

[Dorothee Benz is a writer, organizer, and strategist who has spent decades on the frontlines of social justice struggles in the United States. Follow her on Twitter @DrBenz3. ]

Spread the word