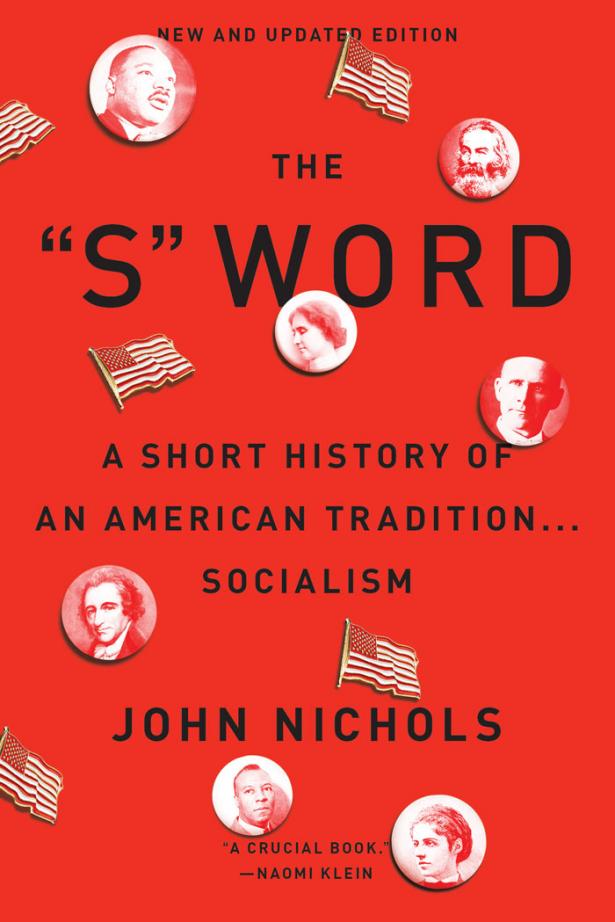

The “S” Word

A Short History of an American Tradition … Socialism

John Nichols

Verso Books

ISBN: 9781784783402

In The “S” Word: A Short History of an American Tradition...Socialism, John Nichols begins with the story of an aging Walt Whitman and his daily meetings with a young writer named Horace Logo Traubel. In Camden, New Jersey, the two had a series of conversations that would lead to a book itself, detailing the thoughts of one of America’s great poets. In addition to discussions about the craft and nature of poetry, they would often talk politics. In reference to a then recent essay titled “Walt Whitman as a Socialist Poet,” Walt said, “Of course, I find I am a good deal more of a socialist than I thought I was.” In Nichols’s newest work, he sets out to show to all Americans that in fact we all are. Released at a time when our strange political discourse has viciously reduced the “s-word” to a variety of wild misinterpretations and misappropriations, Nichols counters this by using the profound historical record to revise the revisionists, in order to save an essential part of our past and hopefully, Nichols feels, our future.

Indeed, Nichols seems to be exactly the man for this much-needed task. Long on the vanguard of a mostly weary American Left, he has spent his career as a journalist avoiding the ease of malaise that so many others on the margins have chosen. As a contributor to In These Times and the Progressive, as well as his wonderful blog for the Nation,his reporting and writing have been epitomized by a worthy combination of reason and passion, along with an optimism that never becomes naïve. This impressive style is on full display in this work, in which he successfully illustrates his indisputable yet often ignored point.

In order to perform the daunting rescue mission of resuscitating our idea of socialism in America, Nichols takes the reader on a journey from the nation’s founding through to the present day, stopping off along the way to illustrate how many of the same people so revered by those who disdain all things and all people socialist were themselves socialists, had clear socialist ideas, and conversed with socialists and even (gasp) communists. Starting with Thomas Paine, the Founder whose pamphlet Common Sense is often attributed as being the spark that ignited the American Revolution, was more than just a town crier bent on personal liberty (as Glenn Beck would like you to believe). Nichols tells the story of Beck’s attempt to “re-write” Common Sense, illustrating wonderfully the ignorance and selective memory held by those who find it necessary or pleasing to forget that Paine himself was a “proponent of taxation, especially progressive taxation for the purpose of redistributing wealth to the poor and the dispossessed. His ideas about guaranteed incomes, national health care and social-welfare schemes earned him recognition as the first great proponent of old-age pensions.” As Nichols points out, these critical details are nowhere to be seen in Beck’s revision of Paine.

And what about the Party of Lincoln? Well, it is here where Nichols argument is perhaps at its strongest. He details the writing of Karl Marx, often celebrating the early incarnation of the Republican Party, and indeed Lincoln himself, something that many of its current day members would loathe to learn. Many glowing articles of America’s new radical party penned by Marx appeared in the New York Tribune. When Lincoln won re-election, Marx wrote him a congratulatory letter. What did Lincoln do to wholly disassociate himself from this evil man? Well, he wrote a letter back of course, accepting Marx’s good wishes “with a sincere and anxious desire that he may be able to prove himself not unworthy of the confidence.” Indeed, most every president up until 1980 engaged socialists, and hired socialists, formed policies ranging from Medicare to anti-poverty legislation to Civil Rights using socialist thought as part of deliberations. Unfortunately for those who pretend otherwise, Lincoln was one such president.

Nichols demonstrates how Martin Luther King Jr., another man whose history Glenn Beck has recently attempted to revise, was strongly influenced by socialism and socialist leaders as he rose to prominence. Nichols’s description of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom as a socialist undertaking underscores this fact, and emphasizes how notions like guaranteed employment and social justice were key elements of the subtext in MLK’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech. Throughout the book, Nichols manages to tell the great story of socialism in America without having to play it up. His strength as a writer is found in the manner in which he treats the facts at hand, and the statements of the various historical players stand as a testament to his idea that socialism has not somehow worked to destroy America, but in fact is responsible for many of the great programs and people that have graced the American stage.

There is much to respect in Nichols’s effort, and there is no doubting that this sort of response was long overdue. However, despite all its qualities, it seems unlikely that the book will do much of anything other than provide those already sympathetic with this cause some anecdotes and evidence with which to argue. Despite the book’s title, Nichols provides scant attention to the history of the word itself, the incredible state of disrepair the language of the Left is in, and the worrying prospect that almost anyone who does not already agree with the underlying ideas of this work would likely reject it out of hand as, well, just another socialist plot to overthrow America. Just how deep the anti-socialist sentiment is sown into the modern American fabric is something not really addressed here by Nichols, even if it is true that we are more socialist than we thought. If that is the case, then why are we so obsessed with pretending we are not? Hopefully, Nichols will attack that issue sometime soon. However, what he has managed to do is deliver a strong, concise history that at least begins the attempt to help America reconnect with those of its roots which are, in fact, socialist.

Spread the word