The story of an awakening must begin with how many had been permitted to sleep in the first place.

I often think back to a Saturday Night Live episode from October 2016, which aired after the release of the Access Hollywood tape. Lin-Manuel Miranda was the guest host, and in the cold open, he directed a line from his fanatically beloved musical Hamilton at a photo of Donald Trump, declaring with ferocity, “You’re never gonna be president now.”

You could feel viewers, Hamilton fans, Democrats, those who for whatever reasons could still afford to believe in norms or justice, laugh with the giddy conviction that a man who grabbed women against their will could never be president, perhaps forgetting that grabbing women against their will had been a habit of presidents all the way back to the characters depicted in … Hamilton. It would be less than four weeks before those who had felt the confidence that misogyny and racism were disqualifying in the United States had that layer of assurance stripped from them.

But even after the election, the fantasies of salvation and order persisted: Someone powerful — Nancy Pelosi, Hillary Clinton, George W. Bush (suddenly looking good by comparison, which should have been a big warning sign), Hamilton itself (remember when the theater audience booed Mike Pence?), Jill Stein (she took all the money, folks!), patriotic Republicans, the Senate, the military, capable advisers who would keep him in check — someone was going to fix this, right?

I was not someone who had believed Donald Trump was never gonna be president; I had spent a long time fearing his victory and the punitive force of the party he was leading to power. And yet, with shame, I vividly recall being assured, in those early months of 2017, by someone who claimed to know, that both Obamas were on it, that they were “talking to people” about what to do. Rationally, I understood it to be fanfiction — wasn’t the fantasy of Obama as savior part of how we got here? — yet the desire to believe that someone with institutional power and a moral compass and a brain was in a position to protect the nation was so strong that, against my will, something like relief briefly washed over me.

Part of that feeling came from an inglorious but sharp desire to abdicate responsibility, to not be alert and vigilant and scared, to retreat to some comforting state of confidence that, even in the face of a long history that suggested otherwise, the people would be ably stewarded through the worst of what might be coming. The desire to sleep is strong.

Four years later, any notion of salvation feels pulled from a fairy tale. The Obamas would not save anyone; Robert Mueller did not save anyone; Ruth Bader Ginsburg and John Lewis are dead, and when they were alive, they weren’t capable of saving anyone either. There were no noble Republicans and too few ferocious Democrats. The fantasy that there are bulwarks in place — individuals or institutions — has been correctly obliterated, leaving little barrier between America’s people and an awareness of their vulnerability to a plunderous ruling class.

This has been the terrible gift of these years. Trump himself is nowhere near the beginning nor the end of the horror, but his reign was a blaring alarm for millions; all the bright lights turned on, the covers ripped off. Those who had been privileged enough to snuggle warm and dumb beneath the blankets of an imagined postfeminist, post-civil-rights, post-Obergefell, post-Obama Camelot found themselves suddenly exposed: cold, shivering, and wide-eyed with fear and realization that the system they’d been taught responds to the will of the people was in fact designed to be able to suppress it.

For millions, the awakening was sudden, bracing, and extremely rude.

Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Getty Images/B) 2017 CQ-Roll Call, Inc. // The Cut

Through one lens, the shock of the past few years has been a right wing getting ever less apologetic about its commitment to authoritarian, anti-democratic minority rule. Trump and his party have surely broken some long-standing American norms and institutions, let others corrode, and encouraged the ones that were left to function as they were built to: keeping power in the hands of the few.

But through another lens, what has actually undergone a startling change has been America’s people, their thinking about the Republic, and, in some cases, their places and responsibilities within it. Some significant portion of the population has been roused to protest — or at least awareness — at a scale that has been seen rarely in our past and that has historically had the power to bring social and political change so eruptive and transformative that those in power will do anything to quell it.

On the first full day of the Trump administration, the U.S. saw the largest one-day protest in its history. The Women’s March — with its pink hats and furiously clever signs and overwhelmingly white vibe and head-spinning roster of speakers, from Madonna to Angela Davis — drew more than 4 million into the streets in the U.S.; nearly 200 more demonstrations occurred across all seven continents.

It’s not that the event marked the revivification of American protest culture or progressive organizing: That story started long before Trump gave his chilling inaugural address to a sparse but newly empowered crowd of brutish acolytes. There had been the Seattle WTO protests in the late ’90s and antiwar demonstrations of the Bush administration. The birth of Black Lives Matter and the Occupy movement, the Fight for Fifteen, Standing Rock, the Climate March of 2014, SlutWalks, Bree Newsome scaling the flagpole to pull down the Confederate flag from the South Carolina statehouse, and the Say Her Name campaign to acknowledge black female victims of police violence; Colin Kaepernick knelt during the playing of the national anthem in the same year that Bernie Sanders’s failed primary campaign against Hillary Clinton took on the dimensions of a left-wing social movement … all of that happened during the Obama administration.

But the spirit of unrest bloomed explosively in the Trump years, in regions and minds long arid of political — let alone progressive — engagement. And the strains of dissent wound round one another in intricate, uneasy ways. The white originators of the Women’s March itself had been pushed by a group of co-chairs who came from other, more deeply rooted protest movements to go further with the event’s stated aims, to proclaim that a “women’s movement” must also by definition be a movement for Black and Indigenous and Palestinian lives, for climate action and in opposition to economic inequality.

And so when, about a week after that first big eruption, Trump issued a travel ban on visitors coming from predominantly Muslim countries, many people new to public displays of fury were quicker than they might otherwise have been to rush to the airports to raise their voices in protest, joining lawyers who had set up shop on the floor trying to help those detained.

In those early months, there were so many protests every weekend, all over the place, for reasons that were ambient but loosely tied together. For a brief time, it was weirdly easy to discern how connected it all was: From a ten-day span in late January and early February 2017, my phone shows pictures of crowds in pussy hats shouting “Immigrants are welcome here” at an anti-ban protest in Washington Square Park, and again at Battery Park (“Muslim rights are human rights”) and at a Yemeni bodega strike in Brooklyn (“Fight ignorance, not immigrants”), and then at a protest winding its way through the streets of Philadelphia, with placards spelling BLACK LIVES MATTER pasted in the windows of an office building in Center City and a man holding a sign that reads THIS JAWN IS YOUR JAWN, THIS JAWN IS MY JAWN.

Later that month, during the confirmation hearing of Jefferson Beauregard Sessions to be Trump’s attorney general, Elizabeth Warren would attempt to read a letter written by Coretta Scott King objecting to Sessions’s 1986 nomination to the federal bench. She was stopped by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, whose reasoning would give form to an Etsy-ready battle cry: “She was warned, she was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” Then the protests got specific. In March, women dressed as handmaids from Margaret Atwood’s dystopian 1985 novel showed up at the Texas Senate building to protest a ban on second-term abortions (a measure that has since been defeated, though not because of the handmaids). And in Washington, D.C., as Congress considered overturning the Affordable Care Act, crowds clogged the halls of the Senate and flooded the phones, pressuring senators until the repeal measure failed and seeding in protesters the notion that action could produce real victories.

Photo: Andres Kudacki // The Cut

The Texas Abortion Protest, May 23, 2017: Activists dressed as characters from The Handmaid’s Tale gathered in the Texas Capitol Rotunda to protest anti-abortion legislation.

Photo: Eric Gay/AP Photo/Copyright 2017 The Associated Press // The Cut

But in August 2017, white supremacists marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting “Jews will not replace us” at a Unite the Right rally, and anti-fascist protesters fought them in the streets. Twenty-year-old DeAndre Harris was beaten in a parking garage by members of the right-wing extremist group League of the South, and 32-year-old counterprotester Heather Heyer was run over by a car and killed, and the starker risks of direct action were made horribly clear.

The capacious fury spread and took new and astonishing forms. In fall 2017, the Me Too movement surged in the wake of New York Times and New Yorker reporting on Harvey Weinstein’s serial predation, revelations that surely landed more powerfully given that an admitted groper was in the White House. Stories of sexual harassment and assault spilled out with tidal force, powerfully reshaping the dominant understanding of how the systems that cover for abuse create an unjust professional sphere. Some powerful people — mostly powerful men — lost jobs in Hollywood and the Senate and the media. The stories reverberated for restaurant and hotel employees and flight attendants and on the Ford factory floor; for months, each story seemed to make room for more stories, compelling more people to come forward.

Years of organizing, including by Fight for Fifteen, were behind the resurgence of the labor movement in some sectors, but Me Too helped fast-food workers, Chicago hotel housekeepers, and Silicon Valley employees draw attention to and amplify longtime complaints about ubiquitous harassment in their industries. In 2018, West Virginia teachers — some who cited either the Women’s March or the Sanders campaign as models for large public actions — kicked off a wave of teachers strikes that would roll, over more than a year, through Kansas, Oklahoma, Virginia, Arizona, Colorado, and California.

Youth activism had been electrified by Occupy and the Sanders campaign, and in March 2018, March for Our Lives, in response to a school shooting in Parkland, Florida, that left 17 dead, became the nation’s largest-ever protest against gun violence. That summer, as images of terrified toddlers separated from refugee parents at our southern border made their way to the public, protesters staged more direct actions — interrupting the dinners of administration officials. California Congresswoman Maxine Waters urged them on: “If you see anybody from that Cabinet in a restaurant, in a department store, at a gasoline station, you get out and you create a crowd and you push back on them and you tell them they’re not welcome anymore, anywhere.” When nearly 600 protesters took over the Hart Senate Office Building atrium, chanting “Abolish ICE,” Senators Kirsten Gillibrand and Elizabeth Warren joined them; Representative Pramila Jayapal was among the 575 arrested that day by Capitol Police.

According to the protest historian L. A. Kauffman, it was that month — June 2018 — that the number of arrests for civil disobedience jumped from an average of 120 per month to more than a thousand. The fall would see hundreds more taken into custody as women (and some men) gathered to oppose the Supreme Court nomination of Brett Kavanaugh, a conservative Federalist Society judge accused by Christine Blasey Ford of having assaulted her when they were teenagers. Protesters filled the halls of Congress and the steps of the Supreme Court, screaming so loudly during the confirmation vote that it had to be paused.

The impulse toward activism and political participation also sowed electoral seeds. In the wake of 2016, record numbers of women ran as first-time candidates, and a record number of them won. The blue wave of 2018 — which saw the election of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Deb Haaland, Katie Porter, Lauren Underwood, Lucy McBath, Rashida Tlaib, and others driven into politics by fury at economic inequality and racism and sexism and climate denialism and Trump himself — was the biggest Democrats had enjoyed since the Nixon administration.

Some of those candidates had been endorsed by a new youth climate group, the Sunrise Movement, which was building support for a Green New Deal, a far-reaching and urgent congressional resolution calling on the federal government to make drastic changes to reduce carbon emissions, digitize the power grid, and create green jobs. A week after the 2018 midterm elections, Sunrise occupied Nancy Pelosi’s office and, in February 2019, confronted Senator Dianne Feinstein about her lack of support for the measure, a video of which was viewed more than 9 million times. In September 2019, 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg led a massive one-day climate strike that inspired 6 million students to walk out of their school buildings globally and 1,100 different strikes to take place across the U.S.

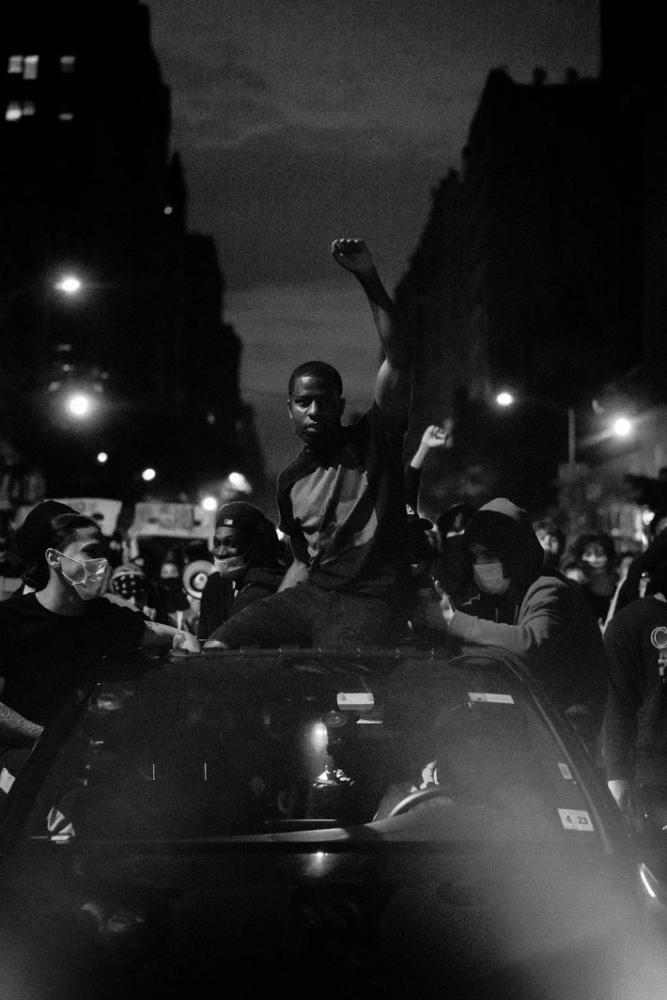

And then came 2020 — a deadly pandemic, lockdowns, hospitals way above capacity, illness and poverty heaped disproportionately on America’s most vulnerable. As millions found themselves shuttered inside, scared for themselves and their loved ones, glued to their phones, they got a vivid view of violent racism: watching Ahmaud Arbery get shot while jogging, hearing George Floyd call for his mother with a knee on his neck, and reading about 26-year-old Breonna Taylor, roused from her bed by police officers who had entered her apartment in the middle of the night looking for drugs that were not there, being hit by six of their bullets and killed.

Even in the grip of fear and grief, with a full view of pandemic peril and the risk of punitive police response and rhetorical backlash, what made most sense to millions who saw those images and heard those stories was to take their fury to the streets.

Over the course of this past summer, Americans insisted that Black lives matter in 2,275 cities and small towns across this country, many of which had never seen a civil-rights protest before. “We’re experiencing a moral reckoning with racism and systemic injustice that has brought a new coalition of conscience to the streets of our country,” said Kamala Harris in her first address to the nation as Joe Biden’s running mate, while in The Atlantic, Adam Serwer argued that “Trump’s presidency has radicalized millions of white Americans who were previously inclined to dismiss systemic racism as a myth, the racial wealth gap as a product of Black cultural pathology, and discriminatory policing as a matter of a few bad apples.”

In June 2020, police took more than 10,000 mostly peaceful protesters into custody across the United States. While the arrests were symptomatic of so much that the protesters were objecting to, they also changed the way many people understood their civic responsibility and their relationship to the state: Tens of thousands of Americans had their first direct encounters with police. So many other thousands protested publicly for the first time (polling suggests that nearly one in five Americans attended a protest between 2016 and 2018 and that 20 percent of them had never done so before); money poured into bail funds. Parents brought their children to marches. People wore masks and videotaped their fellow protesters being hit and dragged away by cops; they worked on campaigns for the first time, registered voters, volunteered to be poll watchers; they read books about structural inequality and tried to learn what intersectionality meant and had their view of history challenged by the New York Times’ “1619 Project” — a rethinking of the American narrative so potent that members of the Republican Party, including Donald Trump and Senator Tom Cotton, have moved to ban it. And as the country changed, so did public opinion: Polls showed majority approval for the protests — about 67 percent of Americans voiced some support for the BLM movement — a change in weeks that was greater than it had been in the previous two years, indicating that even Americans not in the streets were hearing the cries of those who were. Those levels of approval have shrunk (now about 55 percent of Americans say they approve) but not disappeared three months after the height of the protests and after months of backlash law-and-order messaging.

We have been encouraged to see the Trump years as a period of right-wing radicalization. But it’s hard to discount those who began in the moderate or merely apathetic center who have now considered, and in some cases strongly support, policies including the Green New Deal and Medicare for All; they have read, in mainstream publications, arguments for abolishing the police and prisons. So many Americans who had never before engaged actively — learning about, participating — in civic and political life and movements to expand liberty and justice have now done so.

So while the beginning of this period (the Women’s March) and its bookend (the BLM protests of the summer) may feel a million miles apart in spirit and style, a startlingly durable, historically rare thread has connected them: a continued move toward public acknowledgment of inequality, an energetic critique of the systems that govern us. And, with all that, a shift toward the left (or something like it) and some recognition that we are tasked with acting on behalf of our own civil rights and liberties, are responsible for saving our democracy ourselves. We are wide awake now.

Photo: Astrid Riecken/Getty Images/Astrid Riecken // The Cut

Photo: Bill Wechter/Getty Images/2018 Getty Images // The Cut

Except it wasn’t all as neat or noble as that.

For one thing, that “wokeness” got weaponized pretty quickly, turned to a slur, a mocking of the very state of consciousness, which was made to look silly, indulgent, feminine, faddish, and stupid. And while that characterization is the quickest weapon of any opponent of a moral crusade, the caricatures pack their punch because they are not entirely pulled from thin air.

The arrival of these crowds of people who suddenly cared, very broadly, about various forms of amorphous inequality was theoretically great, but what were they there to fight for? What were their demands? Why did they keep making signs that said PROTEST IS THE NEW BRUNCH? Were these crowds of angry people prepared to really dig in? For what and for whom and for how long?

A lot about the nature of the fury — much of it directed so specifically at Trump, a man who was cartoonishly terrible and dangerous, sure, but not so wildly different from plenty of people and policies that had foregrounded his rise, suggested that this was not a long-haul investment in change-making, nor that it was tied to deep moral commitments to justice. For many, it was merely a way to channel their dismay — and perhaps their embarrassment at having been caught by surprise at his election — into something that felt good and self-flattering.

Predictably, a lot of this is about white women — the Wine Moms and Resistance™ warriors mocked most viciously by their white leftist sons (sons who perhaps believed that Joe Rogan’s endorsement could be critical to reaching Ohio voters but that their mom’s weekly meetings of door-knockers were hilariously bourgeois).

It is true that foremost among those who shot out of their beds on November 9, 2016, as if someone had put a fire poker to them were America’s moderate, middle-class white women, who were shocked (in a way that plenty of Black and brown Americans would never have been) that someone like Trump could triumph over someone like them. Some of these white women had never been politically conscious before but have since rebuilt their lives around activism and political engagement. Some, easing in via the Women’s March and then electoral politics, have come to an increasingly complex, progressive view of the world and its inequities.

I reported on a group of newly activated white suburban women back in summer 2017, when they were organizing around Jon Ossoff’s special House race in Georgia. Many have remained politically driven since Ossoff’s loss, working for Stacey Abrams’s 2018 gubernatorial campaign and to help Lucy McBath win the House seat that Ossoff had lost a year earlier. Some describe how the Trump years have sharpened both their understanding of an unjust system and how much they’d previously done to uphold it.

“Jon was this young, good-looking white man who felt comfortable to us,” 51-year-old Jenny Peterson told me in November 2019, observing that “that probably made it easier for us to jump in for the first time. But once we were in, we began to realize how much we had to learn.” She recalled how, while knocking on doors for Abrams and McBath, she met a Black elementary-school teacher, just two years older than she, who said, “I never thought I’d see a white lady from Roswell talking to me about voting for two Black women.” Their conversation prompted Peterson to learn about the history of segregation in her own white suburb.

“There I was, Linda Lollipop on the doorstep, finding out how, two miles from my elementary school, the body of the last Black man officially considered to have been lynched in Fulton County was found in a creek. I’d thought of myself as so aware, but there was all this I was clueless about because the system had been set up so that I wouldn’t learn it. And so that by the time I did, I’d be so entrenched in keeping what I felt was mine that I wouldn’t question it.”

One of the transformative aspects of this period has been that, by participating in protest or activism, in challenging white patriarchal power structures rather than simply supporting and profiting from them, some of these women have gotten a glimmer of what it might be like not to be middle class and white: “I’ve never been in a situation where I’ve looked at so many faces and seen zero empathy,” one white woman told BuzzFeed’s Anne Helen Petersen this summer about participating in a Black Lives Matter protest that drew violent opposition from a biker gang in Bethel, Ohio. “There was just no recognition that they were speaking to other human beings … And it was so bizarre to have a guy in a Confederate bandanna tell me that I better watch where I go, because he’s going to take me to his truck and tear me apart.”

What these white women were experiencing for the first time — the dysphoria of exclusion, alienation, and threat even when they are at home — is familiar to millions of Americans. The growth of movements doesn’t always, or perhaps doesn’t often, stem from altruism, compassion, an impulse toward solidarity, or a keen moral compass; a lot of it is born of self-interest, the realization that it might just be your body on the line.

But for all the white women who have been genuinely and deeply altered in these past four years, there are legions whose only reaction has been to Trump’s vulgarity and not to any of the pre-Trump inequity, along with plenty of others who appear to be in it for the likes, the retweets, the expensive T-shirts.

Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images/2018 Getty Images // The Cut

Is it possible for protest culture to expand too exponentially? Of course, that’s a part of the criticism of many who look askance at the Resistance™ and subscribe to a more puritanical take on activism — that its power stems from clarity of purpose. They point to how much support for BLM has receded since the summer, most notably among white people, how interest in strong gun-control legislation has faded since March for Our Lives, how many eventually grew numb to the horror of child separation. If performance of solidarity is a feel-good patch for people whose commitments are more shallowly rooted, their presence may be as much of a hindrance — an aberration that permits the fantasy of success where no progress has actually been made — as a help.

And yes, a lot of this has been cosplay. For many, gestures (like the empty black squares on Instagram) have stood in for action. Plenty of comfortable people, white people — previously somnambulant, now throwing their fists in the air — don’t really want that much to change, let alone want to commit to doing any actual work; they just want the photo of themselves throwing their fists in the air.

But if movements must be mass in order to make a transformative impact — and there is plenty of evidence that that is true — that mass will need to include the hypocrites and fair-weather friends and grifters and performance artists, too; human beings are messy, and if you want a movement of the people, there’s no getting around … people. Isn’t one of the goals of progressive activism to shift public opinion so thoroughly, to make certain unjust hierarchies so intolerable, so socially unacceptable, that even nonprogressive people, for nonprogressive reasons, feel they must bend to those moral standards? It would be great if people did the right things for the right reasons; short of that, it would be preferable that they did the right things for bad reasons.

I go back and forth about whether it’s possible to genuinely feel hope about this period when I look at the country on a precipice. But it’s the uneasiness of these questions — the seesawing of optimism and pessimism, the internal contradictions and often painful untangling of intentions between those who are now very loosely affiliated with progressive protest — that are, to me, the surest sign that something real has happened to the American consciousness in these past few years. It’s because this process has been so fraught, because paying unwavering attention has been so unpleasant, because staying engaged as our shortcomings are laid bare is hard, because it took bearing witness to brutality past and present to create this spasm of resistance — and yet, so many are still looking directly at it — that I believe we are experiencing our last shot at a Great Awakening.

There is a writhing mass of contradiction and imperfection and disappointment before us. These complexities don’t expose cracks in revolutionary movements; they strengthen them. Inter-left factional fights are not out of line with the history of the movements we were taught to regard as righteous: the women’s movements that emerged out of Black women’s thinking and then were reconfigured around the perspectives and priorities of a white middle class; a civil-rights movement in which women, queer folks, and gender nonconformists were consciously sidelined; a gay-rights movement that erased Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Stormé DeLarverie to foreground the heroics of white cis men; a labor-movement history that is so often told as being about coal miners and teamsters and too rarely acknowledges the propulsive efforts of young female mill workers in Lowell, Black washerwomen in Atlanta, and flight attendants today.

That this is the maddening history of progressive movements does not mean that we should resign ourselves to hypocrisy and internal inconsistency as some sort of twisted inheritance; rather, that one of the most hopeful things about this period is that we have not yet walked away from this knottiness because it is too hard, nor have we accepted it as part of the cost of doing business. In these years, the hypocrisies and inconsistencies have been loudly and insistently called out — starting with the whiteness of the Women’s March; through to this summer, when critic Zoé Samudzi noted that the “Wall of Moms” in Portland, Oregon, who placed their bodies between police and protesters and sang “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” as a lullaby, were using an “affective power” reliant on “white women’s innocence” and the sanctity of white motherhood as its driving force; and into the fall, when Eloquent Rage author Brittney Cooper critiqued prominent Black men like Ice Cube, who were voicing support for Trump, for being “enamored with the kind of masculinity that Trump performs … which is to say they wanna be patriarchs or male dominant in the way that White men are.”

Aspects of this process keep getting referred to as a “reckoning” because it’s a lot easier to say reckoning than it is to say “having all your biases laid out on a table and correctly picked over because it’s time we addressed this shit head-on.” But a feminist movement will be stronger for having been forced to wrestle with the movement away from a carceral system. Activists will be forced to think harder and with more nuance about advocating for the imprisonment of the officers who killed Breonna Taylor, because they are doing so in the midst of a movement that is also questioning the very existence of policing and incarceration practices. None of this is clean or easily digestible, nor should it feel good — alliances can fall apart and descend into angry recrimination. But they don’t have to.

“Argument isn’t an obstacle to the work of historians,” the historian Nicholas Guyatt recently wrote in the New York Times about the raging fights over publication of its “1619 Project,” “it is the work of historians.” It is also the work of activists, as many of those activists have long known. It was in 1983 that Audre Lorde wrote that would-be allies facing their mutual anger “without rejection, without immobility, without silence and without guilt, is in itself a heretical and generative idea. For it assumes that we come together as equals on a common basis to analyze the differences and to change the distortions that history has created around them. It is these distortions that separate us. And what we must ask ourselves is: Who benefits from all this?”

Abusive power structures are built to impede reform and reimagination, in part by ensuring that those who might want to bring them down are also implicated within them. Only drastically incomplete movements could neatly pull at discrete threads of inequity without also pulling up a whole gnarled root system of oppression and complicity. This is it, what so many have just woken up to: an entire system designed to resist uprooting.

And in this, the presidency of Donald Trump has been enormously useful. As a grotesque embodiment of an outrageously powerful tradition, he is a walking showcase of the ways in which so many oppressive interests — capitalism, misogyny, racism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia — are inextricably intertwined. And at least some of the millions of people who have been persuaded that they shoulder some responsibility for removing him have come to see that they also bear some responsibility to act against the forces he has shown them clearly for the first time.

Photo: Eric Demers/Polaris // The Cut

The Wall of Moms, July 23, 2020: The Wall of Moms, a group of mostly white mothers, linked arms to form a barrier between law enforcement and Black Lives Matter protesters at the George Floyd protests in Portland, Oregon.

Photo: Octavio Jones/The New York Times/B) The New York Times // The Cut

Trouble is, this potential inflection point, the kind that perhaps happens once a century, in which a critical mass of people are awake to inequity and have been convinced that they bear some responsibility for making the nation better, is happening as the state structures designed to suppress the masses have grown terrifyingly stronger. While the majority has been opening its mind — perhaps, in fact, because the masses are coming to consciousness — the minority has been extending its power to override that majority.

Trump lost the popular vote, but won the presidency thanks to the Electoral College, an institution originally designed to suppress majority opinion and keep power in the hands of those voting for white-supremacist interests. In four years in the White House, he has appointed a quarter of the federal bench — thanks to a Senate that confirmed those judges and also successfully blocked more than a hundred judicial appointments made by Barack Obama, a president who was popularly elected twice.

This month, Trump got to appoint his third justice, delivering a 6-3 conservative Supreme Court that will shape law for a generation. Barrett will be confirmed by the Senate, a body that has become ever more representative of minority white power over a diverse majority. Her confirmation alongside Roberts and Kavanaugh will mean that one-third of the Court will be composed of justices who worked on the legal team that helped Trump’s Republican predecessor in the White House, George W. Bush, win the presidency via the Electoral College and a Supreme Court decision. Bush, in turn, nominated Roberts to the Court; he is now chief justice. So presidents chosen by a minority of Americans will have shaped the future of Americans’ rights to vote, unionize, gain access to health care, and prioritize the survival of the planet over the profits of corporations by empowering judges who helped them override democracy — and can be counted on in the future to do the same.

A majority of Americans believed Trump should be removed from office, but the Senate — which does not include representation for Washington, D.C., with a population larger than Vermont’s and Wyoming’s, or for Puerto Rico, home to more Americans than at least 21 other states — voted to keep him there. A majority of Americans didn’t want Kavanaugh confirmed to the Court, yet there he sits; a majority didn’t want Trump to nominate RBG’s successor before the election, but here comes Barrett and her commitment to a chillingly conservative jurisprudence.

Now that the mechanisms are nearly all in place, well oiled and humming along efficiently, the roar of the public is growing louder, and those at the controls are getting more open in their aims and no longer need to dress up their project, which is exerting minority control and doing away with even the window dressing of a democracy.

“Democracy isn’t the objective,” Senator Mike Lee tweeted in early October. “Liberty, peace and prospefity are.” Lee is not alone in his recent open disdain for democracy. “Our Founding Fathers hated democracy,” said Washington GOP gubernatorial candidate Loren Culp, a small-town police chief, the week before Lee’s remarks. “Because democracy is mob rule. When the majority rules, the minority is trampled on.” This lays it bare. The language of “mob rule” is what authoritarians use to cast themselves as victims of a roused populace: “Mob justice” is what critics called Me Too; it’s how the right has long referred to the Movement for Black Lives; Trump called those who protested Kavanaugh’s confirmation “an angry mob.” Lee’s formulation is an old trick, the casting of the oppressors as the oppressed.

Tension around whether to leave questions of governance and justice to an American majority is long-standing and extends back to the founding. But in a grotesquely stratified nation, the real worry is about whether to put the protections or rights of an oppressed minority to an empowered majority; it was this dynamic that, for example, led to the failure of some gay-marriage referendums before the tide of public opinion shifted. But protections for the marginalized are not what Lee and Culp are defending, as much as they may be straining to make it sound that way. Instead, they are explicitly arguing against the ability of the governed to select their representation and implicitly arguing for the unchecked authority of a political regime. What does any of this have to do with the awakening to protest and civic activism? It’s how it gets beaten back, made ineffectual. It is also what produced it, to some degree. The question is: Who will win?

When I was in high school, there was an afternoon on which I was leaning slightly on the trunk of a friend’s parent’s car, talking with the friend. All of a sudden, the car started moving backward; I realized in slow motion that I was being run over. I began screaming, my friend began screaming. The car just kept coming. It lasted only a couple of seconds, but I have never forgotten what it felt like to have that metal rolling into my body, the realization that there was nothing I could do to stop it, that my own muscle was unequal to the job, and that there was a good chance that all the yelling in the world wouldn’t be able to halt this car’s slow reverse.

The metaphor is surely infelicitous, given that it was a car that hit and killed Heather Heyer, that police cars were used in cities and towns all through this country this summer to literally run through barricades and protesters. But this is what it means to empower state institutions to simply run through people and their protestations. This is a Kentucky police department that simply doesn’t impose repercussions on officers for murdering Breonna Taylor; it’s a Trump Justice Department that steps in to defend the president against rape charges; it’s a governor and Trump-appointed judges in Florida who can just overturn the will of voters by imposing a poll tax on former felons whom Floridians had overwhelmingly elected to reenfranchise in 2018. At every turn, there is a tool available to those holding power to stop the people from exerting any of their own.

So here we are: In the same period that Americans have been snapped to consciousness at a level larger than any we’ve seen in 60 years, what they have awakened to is a nightmare: the sounds of children screaming at the border; men gasping that they cannot breathe; women revealing that “there were mass hysterectomies” and that what remains “indelible on the hippocampus is the laughter” and making deathbed wishes for a nation, destined to be ignored.

But the nightmare hasn’t just been the ghoulish viscera of suffering. It has also been the closing of escape hatches, diminishing paths to resistance. The awakened and panicked and furious populace may suddenly be running as fast as it can through corridors it has been taught are the paths to progress — voting, organizing, unionizing, bringing lawsuits, registering voters, marching, giving money, educating themselves — but the hallways are collapsing.

It is surely self-regarding and myopic to think today’s situation is more dire, or has a clock on it ticking any more loudly, than it was for previous generations of Americans who, awake to structurally supported violence and inhumanity, fought for better and produced victories, incomplete and temporary, but victories nonetheless. But as the ice caps break apart and so many of our states burn and flood, it’s hard not to ask, with hope and desperation: What — if anything — will we make of our latest, and perhaps last, chance at social revolution?

Photo: Michael Noble Jr./Getty Images/2020 Getty Images // The Cut

The good news is that the minority power, the institutions, the right wing, would not be calcifying around authoritarian rule so brazenly if they didn’t understand the genuine disadvantages of being on the wrong side of public opinion. They see an opposition populace — if not yet an organized opposition party — that is finding new ways to fight them.

The uprisings of the past few years have already succeeded in putting a new generation of combative Democrats in office: The Squad and Katie Porter and Marie Newman and Jamaal Bowman and Cori Bush are in a position to materially alter their party at a federal level, to lead it, and to bolster the efforts of already pugilistic, energetic Democrats, including Warren, Sanders, Jayapal, and Barbara Lee. Meanwhile, candidates and organizations have taken advantage of the recent interest in electoral politics to push more Americans’ attention toward their state legislatures and local government. “Five years ago, if you’d mentioned that Cobb County sheriff to me, I would have been like, ‘There’s a sheriff?’ ” one white woman outside Atlanta told me in 2019. “Now I can tell you his name and who’s running against him” and that at least seven people have died in his custody since 2018.

There are also new economic tools on hand: Sanders broke records during the primary with small-dollar donations; in the month that he announced Harris as his running mate, Biden did too. In the two weeks after Ginsburg’s death, ActBlue raised half a billion dollars, and Jaime Harrison, a Democratic challenger to Lindsey Graham in South Carolina, broke a quarterly record for any Senate candidate, raising $57 million with an average donation of $37, a haul that shows Democrats’ changing relationship to fund-raising not only against a party long funded by billionaires but also to non-presidential campaigns. If, as Citizens United assured us, money is speech, then Democrats are hollering. In October, McConnell complained to lobbyists about his party’s Senate candidates being swamped by small-dollar donations.

Money hasn’t just flowed to the Democratic Party: During this summer’s protests, the civil-rights-advocacy organization Color of Change quadrupled its membership from 1.7 million to 7 million and received hundreds of thousands of individual donations. Bail funds around the country received more than $90 million in the first two weeks of June. Even some of the left’s billionaires have redirected their financial energies; longtime Democratic Party donor Susan Sandler announced in September that she was donating $200 million to racial-justice organizations. “When our government, corporate, and other societal institutions are responsive to — and frankly, fearful of — the people who must bear the brunt of inequality and injustice, then better priorities, practices, and policies follow,” she wrote.

If Democrats win, there is a blueprint, being vocally presented by activists, of what can be done to break the right’s stranglehold on power: passage of a Voting Rights Act; the overturning of Citizens United; statehood for Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico; the end of the judicial filibuster; and court reform not simply on a federal level but at the State Supreme Court level. There are even more road maps: Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, free college and paid family leave and subsidized day care and a wealth tax and prison abolition. Some of these ideas may still be considered radical, but they nonetheless have entered the mainstream lexicon.

Photo: Steven John Irby // The Cut

And of course there are past models for the unlikely victories of people over the mechanisms built to keep them powerless. Enslaved Americans won liberation despite the legal and political erasure of their very humanity; poor immigrant workers extracted protections and concessions from corporate behemoths; those barred from participating in democracy via the franchise have, by waging a battle that lasted centuries and continues today, gained their ballots.

But what these models also suggest is that there will be enormous suffering, sacrifice, and loss ahead. A fight to keep moving forward in the face of institutional obstruction will be arduous, discomfiting; it will take an extremely long time. And that’s not the kind of reality that is going to easily compete with brunch for millions longing to simply return to “normal.”

This is just one of the reasons to fear that Trump and the Republican Party will win in 2020 — with or without the help of the Supreme Court. Yes, because this outcome would offer the right further unchecked power over people and the planet. But also because if enough people believe the problem was Trump — and not the interconnected inequities he embodied and exposed, not the authoritarian, right-wing power grab he made so visible and unadorned — and if the effort to defeat him fails, too many will think their exertions were for naught, rather than understanding them as a crucial early stage in organizing.

But there is a twinned risk: the risk of winning on Election Day. Because if Trump is defeated, if the Senate goes to Democrats, the temptation for too many will be to curl back up and return to slumber.

Coalitions have fallen throughout this country’s history, both after crushing defeats and in the wake of terribly incomplete victories. Activists have treated first-step wins — the Roe decision or the election of a Black president — as glorious endpoints rather than as the beginnings that they are. It is so easy to forget that, as Florynce Kennedy observed, “Freedom is like taking a bath; you’ve got to keep doing it every day,” and that when the fight is for something as fragile as liberty and dignity for the structurally oppressed, there will always be forces strategizing to strip it away again as soon as possible.

And so perhaps the grimmest read of what has happened in these past four years paradoxically offers the greatest hope for an engaged populace going forward: that the results of this right-wing project may be so calamitous, so disastrous for so many millions — a 6-3 Court; corporations given free rein to drill us into destruction; rising seas and raging fires and rampaging plagues — that returning to unconsciousness is simply not going to be possible.

*This article appears in the October 26, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

[Rebecca Traister is writer at large for New York magazine and its website The Cut, and a contributing editor at Elle. A National Magazine Award finalist, she has written about women in politics, media, and entertainment from a feminist perspective for The New Republic and Salon and has also contributed to The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vogue, Glamour and Marie Claire. She is the author of All the Single Ladies and the award-winning Big Girls Don’t Cry.]

Spread the word