How to Celebrate Thanksgiving Without Erasing the Exploitation and Genocide of Native American People

For many people across the U.S., Thanksgiving is about getting together as a family — likely remotely this year, in light of the pandemic — and digging in to a festive feast. What’s often glossed over or erased entirely is the real history behind the holiday, particularly the treatment of Native Americans. But some experts say there are ways to participate in the holiday while also acknowledging its troubling past.

“From the beginning, the story of Thanksgiving has been about telling a romantic story about the relationship between white Americans and the indigenous people of this country,” Stephanie Fryberg, a member of Washington’s Tulalip tribes and professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, tells Yahoo Life. “The irony is that Native people have been sold the same story,” which is one that told the early colonists and natives “sat down amicably and ate together,” Fryberg says, “and the Native Americans helped them survive the winter...and the American colonies just expanded and the Natives just decide to give up the land. And the story ends there and the Natives just die off in history.”

It’s the “myth of Thanksgiving,” Crystal Echo Hawk, a member of the Pawnee Nation and founder and chief executive officer of IllumiNative, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing the visibility of and challenging negative narratives about Native peoples in American society, tells Yahoo Life. It’s a story that “worked to create a history of this country that erased the genocide and brutality of Native peoples,” Echo Hawk says. “As an example, the earliest attempt at declaring Thanksgiving as a holiday was in the 1860s when President Lincoln was trying to unite the country, and he never mentioned Native peoples.”

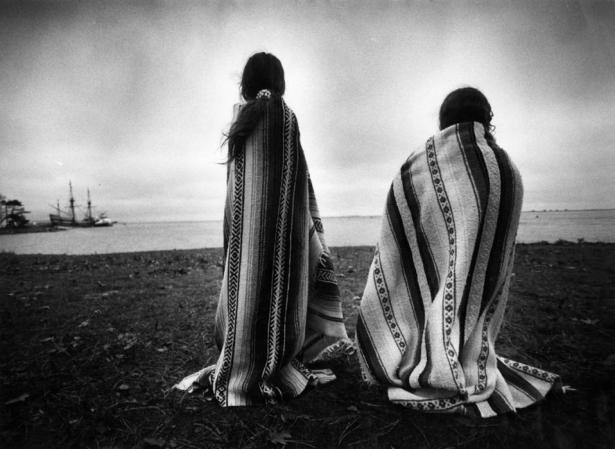

The "myth of Thanksgiving" tells the tale of settlers and Native Americans amicably sharing a meal, erasing realities of exploitation and genocide. (Photo by: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images)

Fryberg says the story that’s often told about the holiday is “so stereotyped” and is “all about erasure.” She adds: “Thanksgiving day is really a celebration of the exploitation and genocide of Native American people.”

She acknowledges that many people grew up thinking the holiday was about “family time” and “gratefulness.” But, she says, “You’re still erasing the true history. Absolutely you can see how you would want to hold onto that positivity — the problem is you’re contributing to a narrative that is problematic.”

Why Thanksgiving is a day of mourning for Native Americans

For many Native Americans, Thanksgiving is not a day of celebration — it’s considered a national day of mourning. According to the United American Indians of New England, “Thanksgiving day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands, and the relentless assault on Native culture.”

The Day of Mourning is “really about truth telling — it pushes back on the myth of Thanksgiving,” says Echo Hawk, who notes that 27 states “make no mention of Native peoples in their K-12 curriculum,” adding: “Of those that do, 87 percent don’t mention Native peoples post-1900. The true history of Indigenous peoples has been erased from history books, from our schools, from media. It’s important that we have narratives and days where we push back and against these harmful myths that only seek to uphold the stories that protect white supremacy.”

Having school children adopt Native American traditions, as seen here in a Denver school in 2002, is exactly what not to do when trying to correct the long-taught myth of Thanksgiving, say experts. (Photo: Cyrus McCrimmon/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Given its painful history, Native Americans like Fryberg prefer that people don’t celebrate Thanksgiving. But for those who do, there are ways to acknowledge the history of the holiday (and its aftermath), as well as the contributions of Native Americans, and incorporate them into the day.

Share the real story of Thanksgiving with your family

Whether you’re sitting around your dining table with your immediate family or having a Zoom call with extended family on Thanksgiving, make an effort to acknowledge Native Americans. “Take the time to talk to your family and acknowledge that while coming together — virtually this year! — is important, it’s also time to learn about the true history of this country,” says Echo Hawk.

For example, according to the National Museum of the American Indian: “The Wampanoag shared their land, food, and knowledge of the environment with the English . Without help from the Wampanoag, the English would not have had the successful harvest that led to the First Thanksgiving. However, cooperation was short lived, as the English continued to attack and encroach upon Wampanoag lands in spite of their agreements.”

Although it can be hard to bring up such a somber topic with your family on the holiday, Fryberg says, “You can’t just default to, ‘We’re just not going to talk about it,’ because you’re literally contributing to the same erasure.”

When talking to children about Thanksgiving, Fryberg says to keep things age-appropriate. But, says Echo Hawk, “Tell them the truth, as hard as it is, as uncomfortable as it can be. We’re all having to do the work of recognizing how our actions uphold these false stories that are biased and harmful. The best thing we can do, what we owe to our children, is a truthful history.”

It's important to acknowledge that traditional Thanksgiving foods — including turkey, pumpkins, cranberries, corn, beans and more — have indigenous roots, say experts. (Photo: Getty Images)

Echo Hawk says that we can’t begin to move forward or end systemic racism in the U.S. until we “acknowledge the role genocide and racism played in the creation of this country.” She says, “It’s the only way we learn. It’s the only way we can do better. It’s the only way we create a better future.”

Serve — or at least talk about — Indigenous foods

While people dig into the turkey and cranberry sauce, most don’t realize or think about the fact that some of the dishes served on Thanksgiving stem from indigenous foods. These include turkey, pumpkins, cranberries, corn, beans, maple syrup, and more.

For example, Native Americans made the first cranberry sauce, according to the Smithsonian, and were “managing and raising turkeys” as early as 1200 to 1400 A.D., according to ScienceDaily. Turkey feathers were used “on arrows, in headdresses and clothing,” according to ScienceDaily. “The meat was used for food. Their bones were used for tools including scratchers used in ritual ceremonies.”

At the Thanksgiving meal, suggests Fryberg, “Talk about why you're eating the foods that you’re eating.”

Look at how your child’s school teaches kids about Thanksgiving

Along with finding age-appropriate ways to teach the real story of Thanksgiving, it’s important for schools to avoid harmful stereotyping and cultural appropriation in lesson plans, such as making and wearing Native American headdresses. “Projects and crafts that attempt to adapt or copy Native traditions tend to perpetuate stereotypes of Native Americans,” according to the National Museum of the American Indian. “For example, we discourage adopting ‘Native’ costumes into your classroom.” Instead, the museum offers some ways here to include more culturally-sensitive lesson plans on Native Americans.

Echo Hawk suggests reading books that center Indigenous history or books that showcase Native Americans today. For kids, the First Nations Development Institute has a recommended reading list of Native American children’s books, and Brightly has its own list of books for children and young adults that celebrate the heritage of Native Americans.

“Learn about and support the continued efforts Native peoples are taking to protect our land, our water, our peoples,” says Echo Hawk. “Follow Indigenous accounts on social media to break out of your echo chamber. Learn about whose land you’re on — not just their history, but how they exist today.” (You can look up which Native American tribes lived in your area with the Native Land map.)

She adds: “You shouldn’t only care about or acknowledge Native peoples during Thanksgiving — we exist and should be celebrated and acknowledged 365 days a year.”

Rachel Grumman Bender is an award-winning health, beauty, and parenting writer and editor. She has written for Self.com, Women’s Health, Prevention, Everyday Health, the New York Post, The New York Times, and many more publications.

Spread the word