This article is part of “Inheritance,” a project about American history and Black life.

“It aims to be a thing of Joy and Beauty, dealing in Happiness, Laughter and Emulation, and designed especially for Kiddies from Six to Sixteen. It will seek to teach Universal Love and Brotherhood for all little folk—black and brown and yellow and white.

Of course, pictures, stories, letters from little ones, games and oh—everything!”

— Introductory note in the first issue of The Brownies’ Book, January 1920

One day in late 1919, a young boy in Philadelphia named Franklin Lewis wrote a letter to a magazine editor at 2 West 13th Street, in New York City:

My mother says you are going to have a magazine about colored boys and girls, and I am very glad. So I am writing to ask you if you will please put in your paper some of the things which colored boys can work at when they grow up. I don’t want to be a doctor, or anything like that. I think I’d like to plan houses for men to build. But one day, down on Broad Street, I was watching some men building houses and I said to a boy there, “When I grow up, I am going to draw a lot of houses like that and have men build them.” The boy was a white boy, and he looked at me and laughed and said, “Colored boys don’t draw houses.”

Why don’t they, Mr. Editor?

My mother says you will explain all this to me in your magazine and will tell me where to learn how to draw a house, for that is what I certainly mean to do. I hope I haven’t made you tired, so no more from your friend.

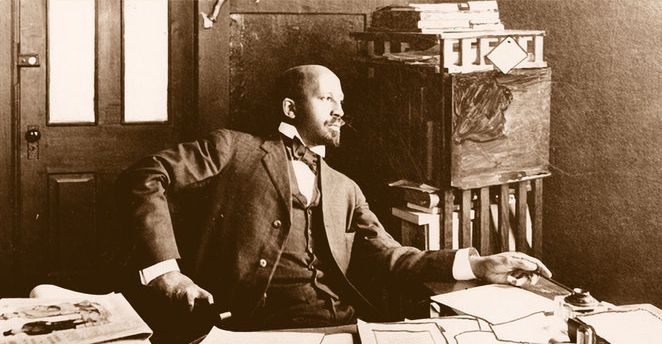

The letter would appear the following year in The Brownies’ Book, a new monthly magazine for Black children. Nothing like it had ever existed before. Created and edited by W. E. B. Du Bois—the sociologist better known for his early civil-rights leadership than his work for kids—it aimed to present a new vision of Black American childhood.

As an early adherent of the “New Negro” movement, which agitated for an American Blackness that—in counterpoint to the more quiescent version offered by Booker T. Washington—was prideful, assertive, confident, progressive, and expressive, as well as economically and professionally successful, Du Bois believed that advancing the race was the work of the next generation.

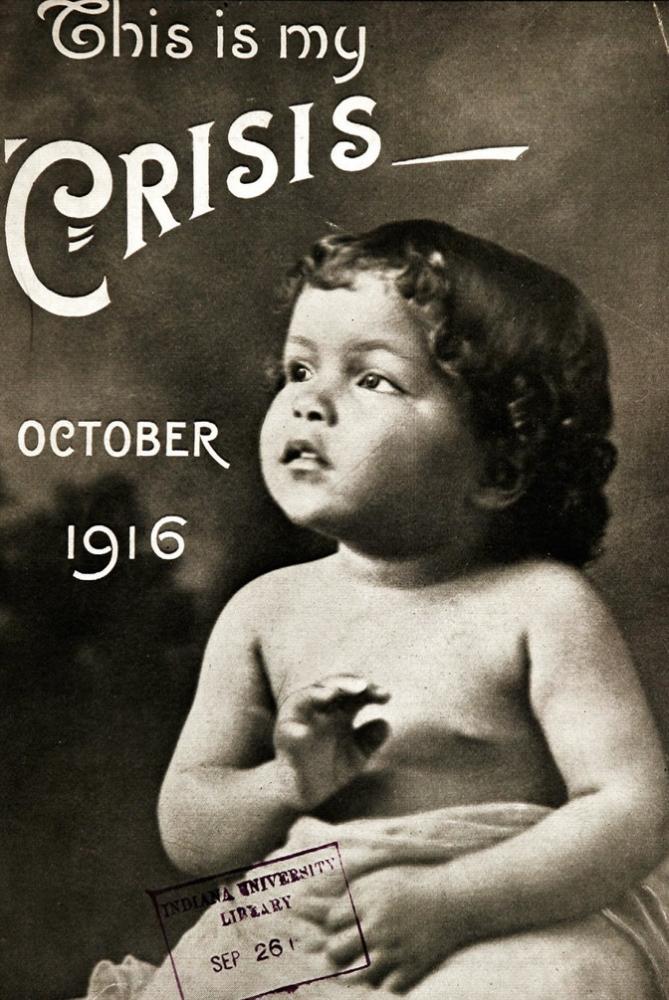

A “Children’s Number” issue of The Crisis from October 1916 (The Crisis / NAACP)

This required that Black children be not just well educated but steeped early on in activism and progressive racial politics. And so in his role as the editor of The Crisis, the house organ of the NAACP, Du Bois had, since 1912, been publishing a special annual issue called “The Children’s Number,” aimed at educating and raising the racial consciousness of Black kids.

But Du Bois had a conundrum. He believed that The Crisis, as a Black news magazine, had an obligation to keep its readers updated on the grim reality of racial violence: the race riots, the beatings, the lynchings. But in 1919—when the “Red Summer” saw white-supremacist riots convulse dozens of cities around the country, killing hundreds of people, most of them Black—those realities had become so grim as to make Du Bois uncomfortable about exposing children to them in the pages of his publication. What hatred, Du Bois asked in a Crisis editorial that October, might reading such reports instill in the young? He quoted with dismay a letter he’d gotten from a 12-year-old “red-bronze and black-curled” girl who wrote, “I hate the white man just as much as he hates me and probably more!”

“And yet, can you blame the child?” he asked.

To the consternation of the Editors of The Crisis we have had to record some horror in nearly every Children’s Number—in 1915, it was Leo Frank; in 1916, the lynching at Gainesville, Fla.; in 1917 and 1918, the riot and court martial at Houston, Tex., etc.

This was inevitable in our role as newspaper—but what effect must it have on our children? To educate them in human hatred is more disastrous to them than to the hated; to seek to raise them in ignorance of their racial identity and peculiar situation is inadvisable—impossible.

His solution was The Brownies’ Book, the seven goals for which he declared would be:

(a) To make colored children realize that being “colored” is a normal, beautiful thing.

(b) To make them familiar with the history and achievements of the Negro race.

(c) To make them know that other colored children have grown into beautiful, useful and famous persons.

(d) To teach them delicately a code of honor and actions in their relations with white children.

(e) To turn their little hurts and resentments into emulation, ambition and love of their own homes and companions.

(f) To point out the best amusements and joys and worth-while things of life.

(g) To inspire them to prepare for definite occupations and duties with a broad spirit of sacrifice.

For the next two years, The Brownies’ Book tried to carry out these goals through its monthly columns, news items, plays, games, poems, and works of fiction. In doing so, it helped launch African American children’s literature as a genre and sparked a reinvention of popular notions of Black childhood.

“De white folks nee-nter putt on airs

About dem wash’out faces,

De culled folks wuz made de fust,

De oldes’ uv de races.

Dey’z kneaded outer mud an’ truck,

An’ den stood up in places

Along de fence to bake ’em dry,

An’ dat’s de on’liest reason why

Dey’s got dem sunburnt faces.Dey had a scrumpshous time ontwel

Ole Nick got on deir traces,

An’ den dey et dat apple up,

An’ fell in deep disgraces;

An’ when dey hearn deir names called out,

Dey run fer hidin’ places,

An’ turnt so pale dey stayed dat way,

An’ dat’s de reason why, folks say,

Dey’s got dem wash’out faces.”— Annie Virginia Culbertson, “The Origin of White Folks,” The Brownies’ Book, January 1920

“The little house is sugar,

Its roof with snow is piled,

And from its tiny window,

Peeps a maple-sugar child”— Langston Hughes,“Winter Sweetness,” The Brownies’ Book, January 1921

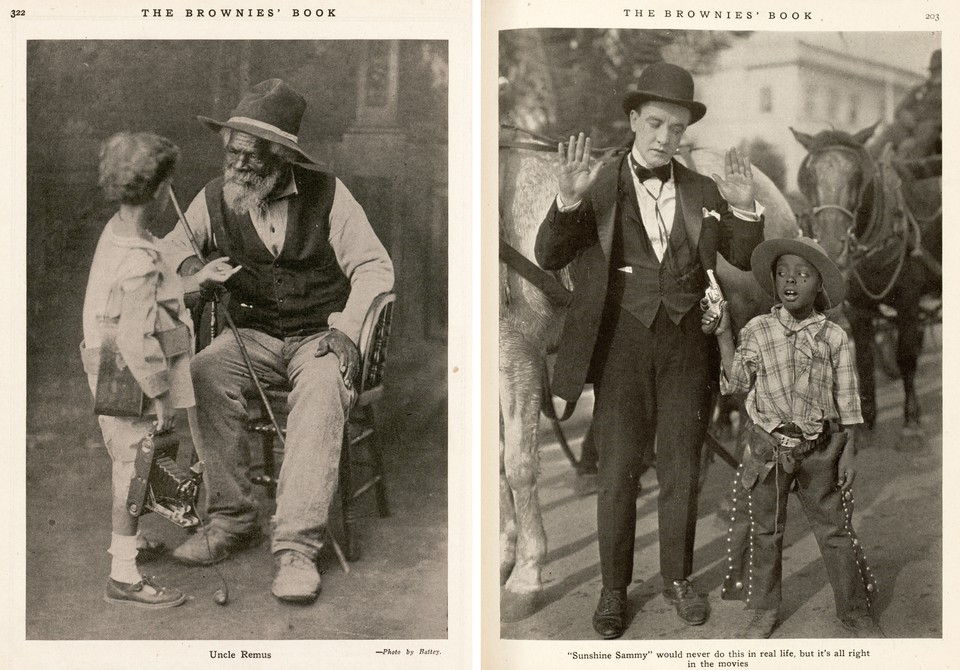

The prevailing, indeed endemic, image of the Black child in the mainstream American culture of the 1920s was the pickaninny—a poorly dressed, unkempt, unmannered caricature with exaggerated features. The most popular and influential children’s magazine at the time, St. Nicholas: Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls and Boys, frequently purveyed the pickaninny caricature, featuring poems with titles like “Ten Little Niggers” and illustrations like one titled “Satisfied” (submitted by a child), which depicted a Black person eating a watermelon.

“The most striking feature of St. Nicholas is the veil of invisibility it confers on [Black children] and their lives,” Rudine Sims Bishop, a leading scholar of African American children’s literature, has written. In a 1965 essay, Elinor Desverney Sinnette, who was a librarian and the acting director of Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, observed that nowhere did St. Nicholas “attempt to recognize the existence of … the Afro-American child and his family … We find the black child in cartoons, an object of ridicule and a buffoon. The impression of the Afro-American child as presented to the white reader is clearly that this black creature is not a part of his society but ‘something’ apart.”

Read: American democracy is hanging by a thread

This was what Du Bois was out to counter. His goal was not to shield Black children from the realities of American racism, but to instill in them a pride and a politics that would help them navigate and overcome it.

Du Bois had a somewhat radical vision of Black children as foot soldiers in the march toward social progress, “exhorted not only to participate in adult political programs but often to lead them,” as Kate Capshaw Smith, a scholar of children’s literature at the University of Connecticut, has put it. But alongside these more avant-garde ideas about the New Negro, Du Bois also espoused rather genteel Victorian ideas about family, comportment, personal responsibility, and morality—what we might now call “respectability politics.” The Brownies’ Book managed to reflect both views, normalizing Black childhood as reflecting American family values while elevating Black political consciousness.

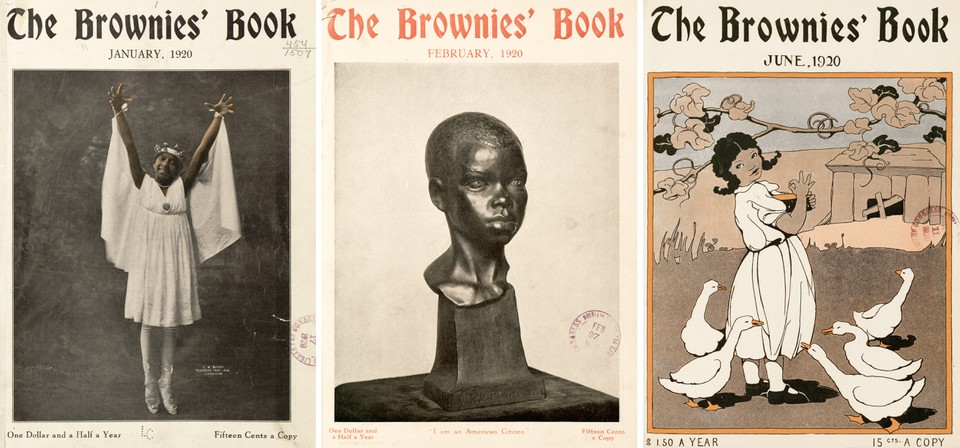

Covers of The Brownies’ Book from 1920 (Library of Congress)

Issues typically ran between 30 and 40 pages. They had striking covers, some of which, like the bust by Paolo Abbate of a young Black boy for the February 1920 issue—“I am an American Citizen,” read the caption—were explicitly political. Other covers featured illustrations of Black children in bucolic settings. Regular features in the magazine included short biographies of notable Black people, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman; a column called “Little People of the Month,” which celebrated the achievements of Black youth; and “Some Little Friends of Ours,” later called “Our Little Friends,” which featured photos of Black babies, usually seated in portrait studios. (Photos like these prompted Gertrude Marean, a white 10-year-old from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to submit a letter kvelling over “the pictures of the little dark babies.”) The magazine also published fiction in a range of modes: reimaginings of antebellum folktales such as the Br’er Rabbit trickster stories; adaptations of African and West Indian proverbs and myths, such as “How Mr. Crocodile Got His Rough Back” and “Mphontholo Ne Shulo”; and florid renderings of classic European fairy tales. The goal, Capshaw Smith explains, was to replace European motifs with African traditions of storytelling, marrying racial pride to the values and stories of Western Europe.

Another regular feature, “The Judge,” was written by Jessie Redmon Fauset, who held the title of literary editor and then managing editor, and did most of the hard work of actually producing the magazine. (Educated at Cornell and the Sorbonne, Fauset also worked as the literary editor of The Crisis, and she became known for her support of Harlem Renaissance writers such as Countee Cullen and Claude McKay, as well as Nella Larsen, who contributed to The Brownies’ Book.) In “The Judge,” Fauset offered didactic sociopolitical commentary and counseled readers on ethics and manners. A complementary section, “The Jury,” featured letters to the editor from children. In a July 1920 letter featured in a section called “Brownie Graduates,” an 18-year-old Cleveland resident named Langston Hughes announced that he had been elected class poet in his high school. In subsequent months, Hughes contributed poems, essays, plays, games, and stories to the magazine. When he came to New York after high school, Fauset introduced him to prominent cultural figures such as Charles S. Johnson and Carl Van Vechten, who brought Hughes’s first book manuscript to Alfred A. Knopf.

An ongoing challenge for The Brownies’ Book was acknowledging the reality of America’s white-supremacist society in a way that was suitable for children. In Du Bois’s own column for the magazine, “As the Crow Flies,” he adopted the persona of a world-traveling (and world-weary) crow who provided a model of racial pride (“I like my black feathers—don’t you?”) while delivering the news of the moment—the quests for Indian and Irish independence, Einstein’s theory of relativity, the international tensions following the First World War—in a dry, declarative style. “For the first time an aeroplane crossed the Atlantic Ocean,” Du Bois wrote in the first issue, in January 1920. He delivered the news straight, but his political interests could be detected in the subjects he returned to more than others—the League of Nations, immigration law, Eugene V. Debs. In July 1921 he made a terse first reference to the “race rioting at Tulsa, Okla.,” returning to it again in the August and September issues.

The instances when Du Bois offered editorial commentary stand out for their wryness and bite. Here are extracts from his March 1920 column:

Congress is trying to frame a bill to keep people from advocating violence and riot. So far, the bills proposed would stop folks from thinking.

United States officials have deported to Russia, 249 foreigners, most of whom have lived in the United States a long time. They were accused of agitating for a change in the government. Most wise people think this is a poor way to answer their arguments.

In February 1921, he made his first mention of the Ku Klux Klan in the column:

When the slaves were freed after the Civil War, there was an attempt to intimidate them and keep them from voting by the organization of masqueraders known as the “Ku Klux Klan”. Recently there has been an attempt to revive this organization as a protest against colored people and Catholics and Jews. The effort is both annoying and funny.

In presenting this news in a fashion appropriate for kids as young as 6, Du Bois achieves a deadpan restraint that is both brilliant and devastating.

“Dear Miss Fauset:

I cannot read very well but I like pictures.

Yours, Sarah L. Woods, Corona, L.I.”

— From “The Jury,” The Brownies’ Book, May 1920

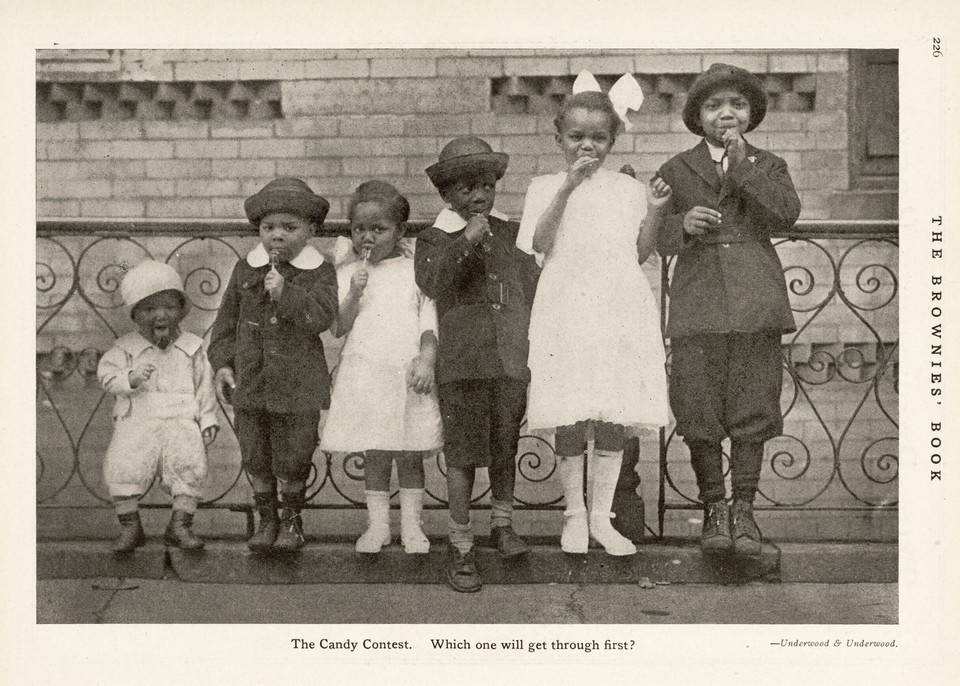

The brownies’ book’s greatest power lay not in what it said but in what it showed. Its images celebrated Black beauty while telling a story of Black childhood as something ordinary and American. Black infants sit, dressed up in their fancy clothes, for portrait photographers, looking adorable. Black children take music lessons. They go to camp. Eat lollipops. Play baseball. Pose for school pictures. Graduate from high school.

“The images were such powerful contradictions of what was created before and during that” time, Violet Harris, an education professor emerita at the University of Illinois who has written extensively about The Brownies’ Book, told me. “These were an antidote to all the despicable negative portrayals in the other materials. It’s a pattern that when people see these images … people tear up and cry.” The net effect of these photos, as Dianne Johnson-Feelings, a scholar of children’s and young-adult literature at the University of South Carolina, told me, was to reinforce readers’ humanity, to send a message counter to the one transmitted incessantly by the larger culture—that the lives of Black children mattered. The images allow them the full humanity that mainstream society of the 1920s denied them.

The Brownies’ Book, August 1920 (Underwood & Underwood / Library of Congress)

Decades later, the prevailing imagery of mainstream American culture was still denying Black children that full humanity. The 1962 classic The Snowy Day, by Ezra Jack Keats, which tells the story of a young boy named Peter as he navigates his urban neighborhood the day after a great snowfall, was inspired by a series of four images from the May 13, 1940, issue of Life magazine. These images featured a Black boy, maybe 4 or 5 years old, getting a blood test for malaria in Liberty County, Georgia. The photos of the boy were the only images in the entire issue of the magazine that didn’t depict Black people as caricatures, subservient, or both (“No suh, boss,” reads the dialogue in one full-page ad). The photos of the nameless boy, sent in by a white reader, have a condescending, anthropological feel. In using the boy as his “model and inspiration” for The Snowy Day, and giving him a name and a story, Keats was perhaps aiming to restore his full humanness and agency.

In a sense, Keats was responding to the Life images much the way The Brownies’ Book responded to the racist tropes in St. Nicholas magazine—rendering Black childhood as something fully normal and American. But here’s the thing: Ezra Jack Keats was white. That the author of perhaps the most well-known kids’ book with a Black protagonist was white—and that today, more than half a century later, the majority of children’s books with Black protagonists are written by white authors—makes what Du Bois and company accomplished with the images in The Brownies’ Book all the more significant.

“I wish you would tell me what to do. I am fifteen years old, and I want to study music. My mother and father object to it very much. They say no colored people can succeed entirely as musicians, that they have to do other things to help make their living, and that I might just as well start doing this first as last. Of course, I say that just because things have been this way, that’s no sign they’ll be like that forever. But they talk me down.

Won’t you tell me what you think about this? And tell me, too, about colored musicians who have made their living by sticking to the thing they love best? Of course, I know about Coleridge-Taylor and Mr. Burleigh.

Augustus Hill, Albany, N.Y.”

— From “The Jury,” The Brownies’ Book, April 1920

Nowadays, the children’s section of every library and bookstore is filled with scores of kid-lit biographies highlighting the exceptional achievement of Black people—portraits of everyone from John Lewis to Shirley Chisholm to Simone Biles. These have roots in The Brownies’ Book.

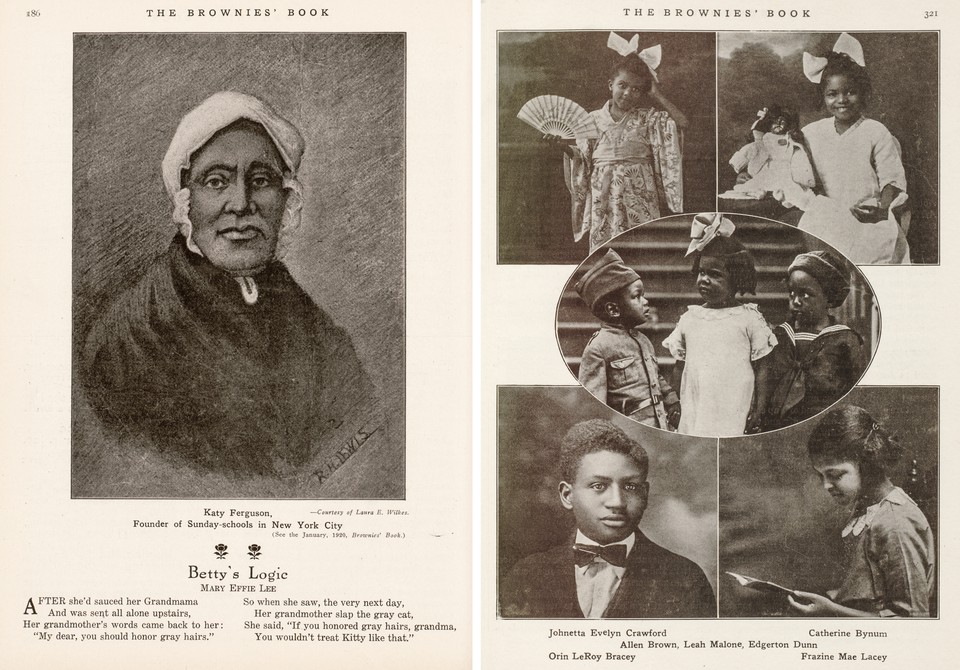

Almost every issue included short biographical sketches featuring well-known historical figures such as Sojourner Truth, Alexandre Dumas, and Phillis Wheatley, and lesser known ones such as Katy Ferguson (the former enslaved person who founded the first Sunday school in New York City, in the late 18th century), Denmark Vesey (executed in 1822 for plotting a slave revolt), and Benjamin Banneker (the polymathic writer/farmer/mathematician son of a formerly enslaved person, who died in 1806).

Left: The Brownies’ Book, June 1920 (Laura E. Wilkes / Library of Congress); Right: The Brownies’ Book, November 1921 (Library of Congress)

Biographies have been especially important to African Americans because, as Jonda McNair, a children’s-literature professor at Ohio State, explained to me, the accomplishments of Black people have been underrepresented in mainstream curricula and culture—and in the 1920s were particularly scant. Thus, The Brownies’ Book’s commitment to showcasing stories of Black achievement can be seen as a radical act. Dianne Johnson-Feelings, with whom McNair collaborated on a volume of essays called A Centennial Celebration of The Brownies’ Book Magazine, to be published next year by the University Press of Mississippi, said that it used to drive her crazy that so much of Black children’s literature is focused on biography, but that she has come to understand how the genre serves to pull children into history. (She herself is now working on a biographical picture book about the crusading journalist and civil-rights pioneer Ida. B. Wells.) In recent weeks, four of the top 10 titles on the New York Times best-seller list for trade picture books were about Vice President Kamala Harris.

“I have never liked history because I always felt that it wasn’t much good,” wrote one Brownie reader, a young New Jerseyan by the name of Pocahontas Foster. “Just a lot of dates and things that some men did, men whom I didn’t know and nobody else whom I knew, knew anything about … But since I read the stories of Paul Cuffee, Blanche K. Bruce and Katy Ferguson, real colored people, whom I feel that I do know because they were brown people like me, I believe I do like history, and I think it is something more than dates.”

“Little babies in a row,

Little dresses white as snow;

No hair, crinkled hair, straight hair, curls—

Lovely little boys and girls!Little children in a ring,

Hear them as they gaily sing!

Red child, yellow child, black child, white—

That’s what makes the ring all right.”— Carrie W. Clifford, “The Kindergarten Song,” The Brownies’ Book, April 1920

“Goodbye dear Brownies! How I shall miss your letters!”

— Jessie Redmon Fauset, “The Jury,” The Brownies’ Book, December 1921

The brownies’ book ended its run after two years because of faltering finances and too-low circulation. (In one issue, Du Bois wrote that the magazine needed 12,000 subscribers to break even, but was languishing at about 5,000.) Advertisements were scarce (one exception was a notorious Madam C. J. Walker ad for “superfine preparations for the hair and for the skin” that seemed to undermine everything The Brownies’ Book was trying to teach its young readers about pride in their skin color and physical beauty), and the economics of sustaining the publication became unviable.

Though its active presence on the cultural landscape was brief, The Brownies’ Book endures as a vision, an ambition, a protest, an argument, an experiment, an archive of history, an embrace, and an influence. (It also made an indelible mark on American culture as a launchpad for Black writers. For instance, Langston Hughes would go on to write and publish books meant specifically for children, such as 1932’s The Dream Keeper and Other Poems.) Other Black periodicals took up The Brownies’ Book mantle; Black newspapers such as The Chicago Defender, The Pittsburgh Courier, and the Baltimore Afro-American began publishing children’s sections in their papers.

WEB DuBois

From 1985 to 2001, the number of children’s books “by and about Black people” published in the United States doubled, according to Rudine Sims Bishop’s 2007 book, Free Within Ourselves: The Development of African American Children’s Literature. The numbers more recently have been somewhat stagnant—according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, the number of titles by and about Black people has increased only 2.5 percent over the past seven years. Still, the number of children’s books created by and for people of color that have won the most prominent awards has notably increased. Last year, Jerry Craft won the Newbery Medal for his book New Kid, making him the fifth African American to win the most exalted award in children’s literature.

The Brownies’ Book’s cultural impact extends into the academy: I’ve been struck by how the lion’s share of the scholarship on the magazine, and on African American children’s literature more broadly, has been conducted by a cohort of women—primarily Black women, including Jonda McNair, Violet Harris, Dianne Johnson-Feelings, Donna Rae McCann, Michelle Martin, and the late Elinor Desverney Sinnette. Many of them are mentees of Bishop, the elder stateswoman of 20th-century African American children’s literature.

Read: Stories of slavery, from those who survived it

“What was so significant was that The Brownies’ Book’s editors were able to capture the underlying ideologies, or things that continue to be an important part of African American children’s literature and continue to resonate,” McNair told me. “That’s why we have books like I Love My Hair!,” the classic 1998 Natasha Tarpley title that urged young African Americans to be proud of their appearance.

“These objectives are still so important, but they are very sad in certain ways,” Johnson-Feelings told me. “One of them has to do with accepting the physical body. And I think that whether or not Black writers and illustrators of today know about The Brownies’ Book, they are still responding to the same kind of imperative.” Harris said she remains “blown away” by the prescience of Du Bois and Fauset’s vision and execution of a magazine for Black children, adding that the only comparable publication in the modern era was Ebony, Jr, which ran in print from 1973 to 1985. There’s been nothing since,” she said.

“I believe in pride of race and lineage and self; in pride of self so deep as to scorn injustice to other selves.”

— W. E. B. Du Bois

Alittle over two years ago, on a brief visit to see my mother in Northern California, I decided to peruse the family collection of photo albums, filled with pictures of my sister and me during our early childhood in the mid-1970s to early 1980s. Playing in a local park. Riding tricycles on the weekends on the walking paths of the college campus nearby. Sitting in a train at a mini amusement park in the next town over, dressed in corduroy pants and paisley prints, the sole Black children in a sea of white ones.

Among the photo albums, I found another relic: my baby book. I hadn’t ever given it much thought; there wasn’t much in it. (My parents’ enthusiasm for documenting every milk bottle and developmental milestone had evidently waned after a few months, when the novelty of a baby daughter was supplanted by the sheer amount of work it took to keep her alive and happy.) But on this trip, I took a close look at it. It was called The Nubian Baby Book. Its cover featured an illustration of a dark-skinned Black infant, wide-eyed and softly gnawing on something.

Published by the Nubian Press in the early 1970s, the baby book featured pastel, mid-century-style illustrations of Black women embracing, feeding, and bathing their beloved Black babies, along with fragments of poems and African proverbs. According to a 1971 item in The New York Times, the book was meant “to familiarize black tots with the Afro-American heritage.” Jet magazine called it “a must for every Black baby.”

But I was most struck by the book’s preface, which felt to me like it was channeling Du Bois:

The legacy which your generation inherits is profoundly a sick society. The power elite of Western civilization has been unable to find solutions to eradicate poverty, war, corruption, racism and oppression. It falls, therefore, to your generation to conceive new values and ways of thought and reasoning which will produce a healthy human society.

In this connection, your contribution can be incalculable. It is necessary, however, to studiously acquire as much knowledge as possible. This accomplishment will reinforce the wisdom which stems from the ancient world of Africa, where highly developed democratic institutions flourished before intrusion of Western civilization.

Clarence L. Holte

Holte, an advertising and public-relations executive who specialized in what were called “ethnic” markets—he helped create a campaign for Old Taylor Bourbon—began the Nubian Press in the early 1970s after a two-decade career with the ad agency BBDO, where he was one of the first Black people to reach the executive suite in an American general-advertising firm. (In the late ’70s, an award was created in his name, the Clarence L. Holte Literary Prize, which would later be bestowed upon Arnold Rampersad, who won the award for the first volume of his biography of Langston Hughes.) Holte was devoted to the study of African American and African history, and he built a substantial collection of African American books and artifacts. I like to imagine that his collection included issues of The Brownies’ Book, whose spirit his Nubian Baby Book embodies. In fact, it almost surely did: On page 18 of the Baby Book, four pages after a poem by Phyllis Wheatley, is a quote from a poem by Jessie Redmon Fauset, “La Vie C’est La Vie,” which was published in 1922, a year after the end of The Brownies’ Book.

Left: The Brownies’ Book, November 1920 (Battey / Library of Congress); Right: The Brownies’ Book, July 1921 (Library of Congress)

“Going out into their 1920 world, black children faced every sign, symbol, slogan, and slight needed to convince them they were second best, at best,” Marian Wright Edelman, the founder of the Children’s Defense Fund, has observed, in writing about The Brownies’ Book. “But reading an essay by Langston Hughes or Nella Larsen, answering a quiz about the contributions of heroes and heroines of their race, reading profiles of their forebears, and seeing children who looked like them in photos and drawings was a strong antidote.”

The express purpose of The Brownies’ Book was to show children that being Black is normal in a world determined to convince them that it was not. But to say that Black childhood was normal was not to say that it was the same as white childhood. If white childhood in America was oblivious and heedlessly jingoistic, Black childhood was socially attuned, politically self-aware. Before she died, Elinor Desverney Sinnette noted striking contrasts in how St. Nicholas and The Brownies’ Book covered the world. Here’s how St. Nicholas covered the news of revolution in Mexico in April 1920: “Those restless people beyond the Rio Grande spent the month of April in their favorite pastime—Civil War.” The Brownies’ Book coverage was more sophisticated and mature: “There has been a revolution in Mexico. President Carranza has been expelled and General Obregon is at the head of most of the opposing forces. The trouble seems to have been that Carranza was not willing to have what his rivals considered a fair election.”And here’s a striking contrast of images from the same year, 1920: Whereas the July issue of St. Nicholas showed 30,000 schoolboys parading in the May Day Americanization parade and a group of white children sitting on guns aboard the USS Pennsylvania, feeling proud to be “a niece or nephew of Uncle Sam,” the January issue of The Brownies’ Book showed Black children marching in protest of lynchings and other racist violence. Out of painful necessity, Black childhood is better examined, more self-aware.

The January 1920 issue showed children in the “Silent Protest” Parade in New York City. (Underwood & Underwood / Library of Congress)

The Brownies’ Book and The Nubian Baby Book (and The Snowy Day and I Love My Hair!) counter the assumed default ways of living, being, and looking—that, for example, good, “real” American children are white and innocent. Of course, plenty of American children were not white, and even innocent white children could be heedless and cruel in their racism: The June 1920 issue featured a devastating letter from a Brownie reader in Philadelphia, Alice Martin, who described how white students in her geography class, looking at a photograph of an African person in a textbook, turned toward her and laughed.

The Brownies’ Book empowered its Black readers by calling out racism where it was found, even to the point of naming names. When a Brownie named Ammie Rosealia Lewis, of Imperial County, California, graduated as the valedictorian from Calexico High School, five of her white classmates—two girls and three boys—refused to sit next to her. “They could not bear to recognize that a Negro should be an honor student,” the “Little People of the Month” column from September 2020 declared. I take an indecent amount of pleasure from the fact that The Brownies’ Book published the white students’ full names.

ANNA HOLMES is an award-winning editor, writer, and executive producer. She is currently the creative director of Higher Ground Productions, the podcast, television, and film company created by Michelle Obama and President Barack Obama.

Give The Atlantic Share a year’s worth of stories that enlighten, challenge, and delight.

Spread the word