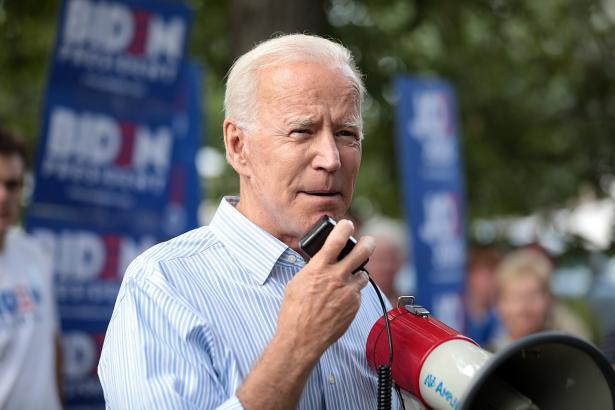

After Democrats in March voted down a national $15 minimum wage, President Biden signed an executive order raising it for federal contractors to $15 an hour by 2022. This is an excellent if insufficient step, both for the national Fight for $15 and for low-wage federal contractors. It’s heartening to see the president use the powers of the executive branch to improve workers’ lives when faced with a setback in Congress. But this is far from the most powerful move Biden, who has proclaimed himself “the most pro-union president,” could make with the power of procurement. With the stroke of a pen, he could reinvigorate the American labor movement by prioritizing workplaces with collective-bargaining agreements for federal contracts.

The government spent over $586 billion on federal contracts in fiscal year 2018, long before it spent trillions addressing the COVID-19 crisis. These funds finance millions of contract workers, according to a Brookings Institution study. They stretch across almost every industry in the American economy, from construction to technology, defense to health care. Compared to workers directly employed by the federal government, however, few of these contractors are unionized. If Biden is to govern as the serious “union guy” he claimed to be on the campaign trail, he could order the federal government’s massive contracting apparatus to exclusively hire union workplaces, “unless there is no such supplier that can perform that contract at a reasonable cost or comparable quality,” as labor lawyer and author Thomas Geoghegan wrote.

What, you might ask, would be the legal basis of such a determination? The basic foundation of labor law in this country. The National Labor Relations Act remains the law of the land and holds that it is “the policy of the United States” to encourage “the practice and procedure of collective bargaining.”

Actually taking this long-standing law seriously would turn the tables on big business, forcing them to drop their staunch opposition to unions if they ever wanted a public contract again. Major companies as diverse as UnitedHealth Group, Deloitte, AT&T, and Lockheed Martin take on federal contracts. This would open the floodgates to new organizing in the private sector, where employers have waged brutal, well-funded opposition campaigns to combat unions. One can only imagine how different the failed Bessemer, Alabama, RWDSU drive would have been if Amazon, a major federal contractor, did not spend big opposing its employees. It would help buoy private-sector unions whose membership rolls have been declining for decades.

Read more from the Revolving Door Project

Unions like the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers would be poised for a membership explosion, considering their existing footholds among federal defense contractors are a drop in the bucket compared to the scale of the Defense Department’s aerospace contracting. Health care workers’ unions like National Nurses United could recruit thousands of new members employed by the Veterans Affairs Department’s contracting. And the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers can only dream of easily unionizing utility workers servicing tens of billions of dollars of Department of Energy contracts.

Big Tech companies like Google, Microsoft, IBM, and HP, which manage major federal contracts, would be forced to drop their opposition to unions at their workplaces. This would clear the biggest hurdle the burgeoning white-collar tech and professional workforce has to organizing. Workers struggling to build the Alphabet Workers Union would receive a major boost if Google were forced to drop its opposition to keep its lucrative Defense Department contracts. And so would the millions of workers providing professional IT, engineering, program evaluation, or technical skills to the federal government through contracts held by any number of companies, big or small. Biden could spark worker organizing in new industries at a scale we have not seen since World War II, if he chose to.

Many businesses, historically unafraid of breaking labor law, might form company unions to remain eligible for contracts. Legitimate unions, however, have long fought to root out compromised management organizations in their midst. And existing labor law already outlaws such abusive arrangements. Important questions remain about how unions would remain independent from companies that may actually encourage unionization.

To answer this, one has to realize how unique the extreme anti-union behavior of American companies is compared to Europe. Few European countries allow companies to brazenly interfere in union elections like they do in the U.S. Instead, tripartite models in places like Finland officially craft economic and industrial policy with powerful unions, business, and the public at the table. Collective bargaining can be state policy and unions can still retain their independence, not to mention the elections every union holds periodically to choose new leadership. Despite these quibbles at the margin, the upsides of mass unionization far outweigh any potential conflicts of interest.

There are, of course, legal limits to Biden’s ability to promote unions. He cannot, for example, mandate employer neutrality, even at businesses that work for the federal government. Employers are explicitly guaranteed the right to oppose unions in their workplace by Taft-Hartley, the 1947 law that has put a straitjacket on labor for the last 70 years. Such an executive order would also be viciously fought by anti-union employers in the courts, but labor lawyers like Geoghegan and Brandon Magner have already thought through potential legal challenges. They conclude that the federal government’s contracting authority is so broad, and the National Labor Relations Act’s endorsement of collective bargaining so clear, that an executive order requiring collective bargaining in return for federal dollars would pass legal muster.

Like student debt cancellation, the real challenge is passing the Biden administration’s self-imposed hesitancy. Remembering history may help with that.

Franklin Roosevelt fundamentally reshaped the American labor landscape with both executive orders and new laws. Before overseeing the advent of a 40-hour workweek, FDR proposed shortening the work week to 30 hours to increase employment. He worked with unions to pass laws from the National Industrial Recovery Act to the Wagner Act, over the deafening cries of business, to guarantee the right to collectively bargain. His administration made employers recognize unions and forced them to bargain before labor boards created by executive order. His National Recovery Administration even introduced national industrial policy to the economy, setting industry-wide wage standards, price controls, and production quotas before it was struck down by a hyper-conservative Supreme Court.

A simple executive order on federal contracting seems small in comparison.

As the fight for the PRO Act continues, unions should be aware of the massive power Biden alone wields to make organizing easier. Even if that bill passes, unions should demand that Biden use the executive branch to deliver for his core constituency. Student debt activists provide a model. They identified the president’s power to cancel student debt and used it as a hammer to make debt cancellation a political issue every primary candidate staked a position on. Unions could do the same.

Biden already recorded a video that will be used to explain the benefits of unions at organizing drives for years to come. His promises to “hold company executives personally liable” and make them “pay a personal price” for union-busting have yet to materialize, despite his pledge “to be the strongest labor president you have ever had!” While his Labor Department picks are very promising, it will take more than administrative relief to reverse the labor movement’s long decline. This single order would go a long way.

Elias Alsbergas is a research assistant with the Revolving Door Project who previously worked as a strategic research analyst for the Machinists Union and as a public-transit labor organizer for the Amalgamated Transit Union.

The Revolving Door Project, a Prospect partner, scrutinizes the executive branch and presidential power. Follow them at therevolvingdoorproject.org.

Spread the word