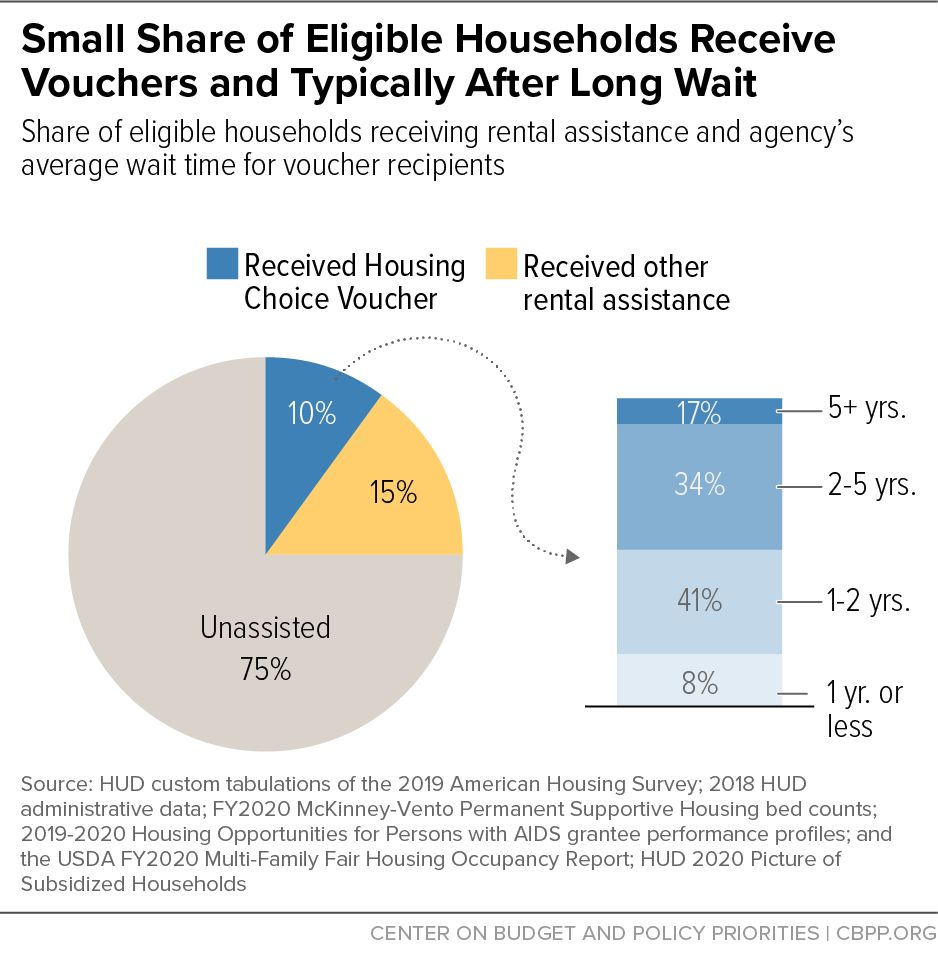

Due to limited program funding, families struggling to afford housing that manage to get off the waiting list for a Housing Choice Voucher must typically wait for years before receiving a voucher, CBPP analysis of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) data shows. Among the 50 largest housing agencies, only two have average wait times of under a year for families that have made it off of the waiting list; the longest have average wait times of up to eight years. On average nationally, families that received vouchers had spent close to two and a half years on waitlists first, exposing many to homelessness, overcrowding, eviction, and other hardship while they wait. (See the Appendix for data on average wait times by state and among the largest agencies.)

Moreover, these figures understate the unmet need for assistance. Millions of other families eligible for rental assistance never receive it because their names never rise to the top of the waiting list or they live in communities where the housing agency has closed or doesn’t keep a waiting list. Also, because of insufficient funding, local housing agencies often prioritize specific groups for available vouchers such as veterans, working families, or people fleeing domestic violence or experiencing homelessness. Setting priorities in the face of limited funding makes sense, but it means that families that need help paying for housing but fall outside the priority groups may never get assistance. For all of these reasons, an agency’s average wait for people receiving vouchers does not reflect the average wait for someone who puts their names on a waiting list for one.

Significantly expanding the federally funded voucher program would help more people access rental assistance when they first need it instead of facing years of hardship.Significantly expanding the federally funded voucher program, which helps households with low incomes rent a modest unit of their choice in the private market, would help more people access rental assistance when they first need it instead of facing years of hardship. A top priority for policymakers in the upcoming recovery package should be to provide substantial, multi-year funding for new housing vouchers.

The state and local housing agencies that administer the voucher program use virtually all the voucher assistance funds they receive, but a shortage of resources for rental assistance leaves the vast majority of eligible households without aid. In 2019, for example, 2 million households used vouchers to rent housing but more than 16 million unassisted renter households paid more than 30 percent of their income for housing or lived in substandard or overcrowded homes. (The federal government considers housing unaffordable if it exceeds 30 percent of income.) Households on agency waiting lists typically continue to experience homelessness, overcrowding, or other housing insecurity for years before receiving a voucher. And many other households needing vouchers either don’t get on a waitlist — 53 percent of agencies had closed their waiting lists to additional applicants, a 2016 survey found — or drop off without ever obtaining assistance, even after waiting years.

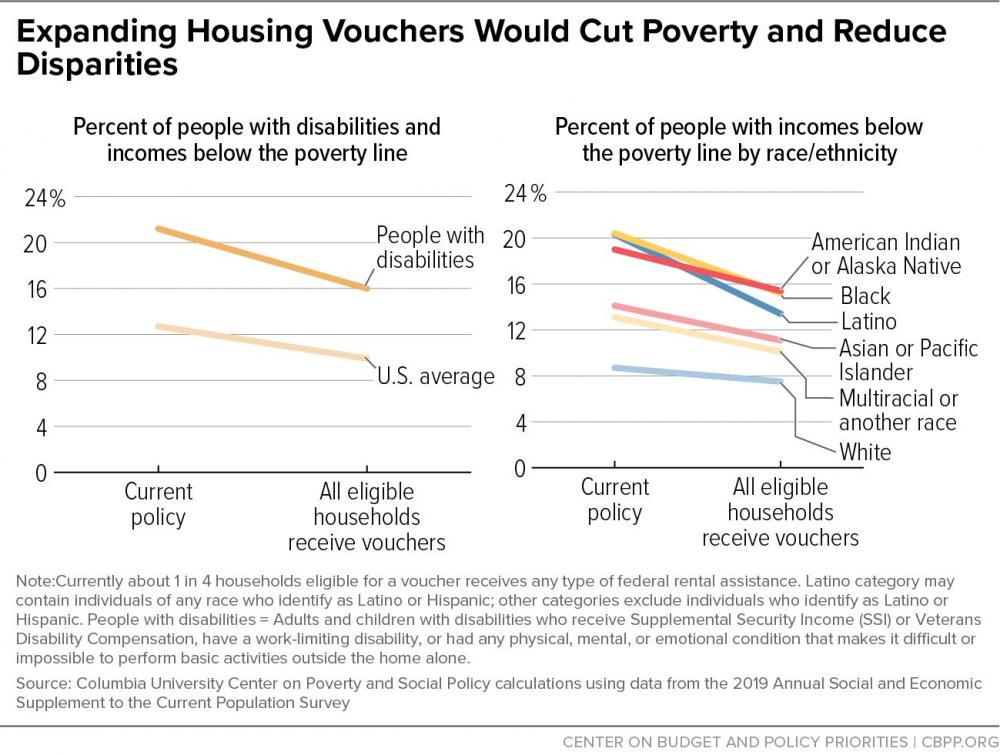

Housing vouchers, when available, are highly effective at reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding and at improving other outcomes for families and children, rigorous research shows. They also give people with low incomes greater choice about where they live, enabling them to move to neighborhoods with lower poverty rates and more resources. Expanding the program could lift millions of people out of poverty. It also would reduce racial inequity: the housing affordability challenges that vouchers address are heavily concentrated among people with the lowest incomes and, due to a long history of racial discrimination that has limited their economic and housing opportunities, among people of color.

Inadequate Funding Creates Long Waits

The Housing Choice Voucher program, the nation’s largest form of rental assistance, offers a proven, evidence-based tool to address housing hardship. Currently it enables roughly 2.3 million households with low incomes to afford decent, stable housing. The family pays about 30 percent of its income for rent and utilities, a widely used standard for the amount a household can reasonably be expected to pay for housing. The voucher covers the rest, up to a cap based on HUD estimates of typical market rents in the local area.

Despite the demonstrated benefits of rental assistance and effectiveness of vouchers specifically, resources fall far short of need. Only 1 in 4 households eligible for rental assistance receive it due to funding limitations. Because the need is so much greater than the supply of vouchers, housing agencies establish waitlists for households interested in receiving assistance, and for each agency HUD publishes the average time someone who received a voucher had to first wait for assistance. While these data leave out millions of people in need who never get a voucher (see discussion below), they provide a useful indicator of the inadequacy of federal rental assistance funding by showing how long even people who succeed in obtaining a voucher must endure hardship before receiving help.

The Appendix tables show average wait times for people who used a voucher in 2020 by state and housing authority. Wait times among assisted households vary across the country but average close to two and a half years (28 months) nationally. Averages by state range from nine months in Nebraska and West Virginia to five years in Alabama. The average wait time for individual housing agencies is much more variable; many agencies report years-long waits. Of the 50 largest housing agencies, only two — the housing authorities in Dallas, Texas, and Columbus, Ohio, have wait times under one year (specifically, eight months). But in many cases — including in Dallas and Columbus — shorter waiting times do not reflect ready availability of assistance. Families interested in applying for assistance in Dallas must first submit a preliminary application that will then be randomly selected to be placed on the waiting list. People who ultimately get assistance spend a relatively short time on the waiting list, but their overall wait time is much longer since they first had to wait to get on the list. Households in Columbus can apply directly to the waitlist but join a list of more than 25,000 others, indicating that most households seeking assistance today would almost certainly face a wait time much longer than eight months.

The longest wait times among these large agencies are more than seven years in San Diego County, California, where there were 56,737 families on the waitlist at the end of 2020, and eight years in Miami-Dade, Florida, where the housing agency is processing applications it received during its most recent open enrollment period 13 years ago, in 2008.

Importantly, long waiting times are not due to agencies failing to spend their voucher funding. Over the past decade they have spent virtually every dollar that lawmakers have provided for vouchers. In a given year, an agency might sometimes spend modestly less than 100 percent of its voucher funding for the year and sometimes modestly more (by drawing down reserves), but from 2011 to 2020, agencies overall spent 99.9 percent of the funding they received, on average. Even in 2020, when the pandemic disrupted program operations, they spent 99.3 percent.

Extended Waits Prolong Hardship, Risk Lasting Harm

Households waiting for a voucher continue to lack a decent, stable home, which can cause serious hardship even when the wait is relatively short. Many of these families are paying large shares of their income for housing, which leaves them with less for food, medicine, child care, and other necessities and places them at risk of losing their home if faced with an unexpected expense or income decrease.

Many families and individuals on voucher waiting lists may face eviction and end up doubling or tripling up with other households, moving between friends and relatives’ homes, or experiencing homelessness. This instability causes stress, can interrupt children’s learning (especially if they have to change schools), and can make finding and holding a job far more difficult. Homelessness has lasting impacts; among children it is associated with increased likelihood of cognitive and mental health problems; physical health problems such as asthma, physical assaults, and accidental injuries; and poor school performance. A wait of several years could expose children to hardship through much or all of their early childhood, with potentially far-reaching damage to their development and chances of academic and financial success.

Though the demographics of people on waitlists vary by the housing agency’s location and size, households with extremely low incomes — defined as below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the area median income, whichever is higher — are consistently the majority (74 percent across all agencies) of those waiting. On average, 60 percent of households on waitlists are families with children, 11 percent are older adults, and 18 percent include at least one person with a disability.

Black, Latino, and Native American people are disproportionately likely to experience housing insecurity and homelessness due to a long history of racist housing policies and racial discrimination that has limited their economic opportunities, and one survey shows that Black households are disproportionately represented on waitlists, on average. In fact, 66 percent of households on waiting lists at large housing agencies (those with 3,000 or more units) are Black.

Wait Times Understate How Long Households Seeking Housing Assistance May Have to Wait for Help

Data on waitlists do not show the full extent of need or demand. Many housing agencies have closed their voucher waitlist because applications far exceed the number of vouchers they can administer. In fact, one 2016 survey found that 53 percent of voucher waiting lists are closed to new applicants, nearly two-thirds of which had been closed for at least a year. In addition, many low-income households may not put their name on a waitlist even if they are facing some form of housing instability because they know any help would be years away.

Also, data on average wait times only reflect how long people who ultimately received a voucher had to wait for assistance. Given the lengthy waits, some families may drop off the list without ever obtaining assistance, even after waiting years.

Furthermore, more than 60 percent of housing agencies prioritize their vouchers for certain populations, such as veterans, people fleeing domestic violence, working families, older adults, or those experiencing homelessness, to best fit their communities’ needs. Households in these populations may have a shorter wait for vouchers, but the wait for other households served by that agency may far exceed the agency’s average. Indeed, households that don’t fall into a priority category may never come off of the waiting list.

Unfortunately, HUD does not keep systematic data on the number of people on waiting lists, the average wait for people currently on waitlists, or which agencies have closed their lists altogether. Such data would show that many of those still on a waiting list have already waited far longer than the average wait times for people who are selected to receive a voucher.

Expanding Vouchers Would Reduce Wait Times, Housing Insecurity

Some 16 million renter households paid more than 30 percent of their income for housing or lived in overcrowded or substandard housing in 2019. Some 5.7 million of them are working households. Because many jobs do not pay enough to enable workers to afford housing and housing costs have outpaced income growth, nearly 1 in 5 working renter households paid over half their income for housing in 2018. In addition, 580,000 people experienced homelessness in January 2020, according to HUD’s annual point-in-time count. These housing problems are linked to cascading harm in other aspects of families’ lives, including adverse effects on children’s health, development, and educational success.

Vouchers offer a proven solution and expanding Housing Choice Vouchers would help more people receive assistance when they first need it. Rigorous research shows that Housing Choice Vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding. By lowering rental costs, vouchers also allow low-income people to spend more on other basic needs like food and medicine, as well as on goods and services that foster their children’s healthy development. They also provide people with low incomes greater choice about where they live, allowing them to make decisions based on what works best for them. When families choose to use their voucher to move from a neighborhood with a high poverty rate and lack of investments to a neighborhood with low poverty rates and more resources, research shows the children have substantially higher college attendance rates and adult earnings than peers who grew up in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty. Adults in these families have improved mental health and lower rates of diabetes and extreme obesity.

Providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line and cut the child poverty rate by a third, a Columbia University study estimated. It also would shrink the gaps in poverty rates between white and Black households (by over a third) and between white and Hispanic households (by nearly half). And it would significantly reduce poverty disparities for people with disabilities. (See Figure 2.)

Recovery Legislation Offers Opportunity to Help More Households Afford Housing

As Congress crafts an economic recovery package, a top priority should be to expand vouchers to more people in need. The COVID-19 pandemic and recession have caused even greater housing hardship, and while the federal government has provided substantial emergency housing assistance, this is not designed to address the overwhelming need that existed before the pandemic. Ultimately, housing vouchers should be available to everyone who is eligible, as President Biden proposed during the presidential campaign. At a minimum, recovery legislation should make a sizeable down payment toward this goal.

Recovery legislation should invest both in housing vouchers and in the supply of affordable housing, for new construction and renovation. While supply investments can help communities with too few reasonably priced units to expand access to affordable housing, supply investments by themselves don’t create housing that is affordable to the lowest-income households, which need assistance to afford even those lower priced units. Moreover, in many communities, there is an ample supply of reasonably priced housing (that is the price reflects the cost of operating the housing and hasn’t been bid up by a lack of supply), but households with low incomes need help bridging the gap between their income and the cost of rent.

End Notes

CBPP, “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program,” updated April 12, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/the-housing-choice-voucher-program.

The tables do not include data from agencies participating in the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration program. Since participating agencies are subject to different program and reporting rules, much of their data on waiting times is missing from HUD’s database.

Dallas Housing Authority, “Learn About the Housing Choice Voucher Program,” https://dhantx.com/applicants-residents/housing-choice-voucher-program/ .

Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority, “5-Year PHA Plan,” January 2021, https://cmhanet.com/Content/Documents/5-Year-Plan.pdf.

Housing Authority of the County of San Diego, “Public Housing Agency Plans,” July 2021, https://www.sandiegocounty.gov/content/dam/sdc/sdhcd/new-docs/2021-Board-Approved-Agency-Plan-HUD-Submission.pdf.

Miami-Dade County Public Housing and Community Development, “5-Year PHA Plan,” October 2019, https://www.miamidade.gov/housing/library/notices/2019-2020-5-year-pha-plan.pdf.

Will Fischer, “Rental Markets Can Absorb Many Additional Housing Vouchers,” CBPP, May 28, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/rental-markets-can-absorb-many-additional-housing-vouchers.

LaDonna Pavetti, “Children in Distress Due to Increased Hardship: An Interview With Dr. Philip A. Fisher,” CBPP, February 23, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/children-in-distress-due-to-increased-hardship-an-interview-with-dr-philip-a-fisher.

Sonya Acosta, Anna Bailey, and Peggy Bailey, “Extend CARES Act Eviction Moratorium, Combine with Rental Assistance to Promote Housing Stability,” CBPP, July 27, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/extend-cares-act-eviction-moratorium-combine-with-rental-assistance-to-promote.

Andrew Aurand et al., “The Long Wait for a Home,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, Fall 2016, http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/HousingSpotlight_6-1_int.pdf.

CBPP, “Majority of Low-Income Renters with Severe Cost Burdens Are People of Color,” May 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/majority-of-low-income-renters-with-severe-cost-burdens-are-people-of-color.

Meghan Henry et al., “The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, January 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Government Segregated America, Liveright, 2017.

Public and Affordable Housing Research Corporation, “Housing Agency Waiting Lists and the Demand for Housing Assistance,” February 2016, https://www.housingcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/waiting-list-spotlight.pdf.

CBPP, “Three in Four Low-Income At-Risk Renters Do Not Receive Federal Rental Assistance,” updated July 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/three-out-of-four-low-income-at-risk-renters-do-not-receive-federal-rental-assistance.

Erik Gartland, “2019 Income-Rent Gap Underscores Need for Rental Assistance, Census Data Show,” CBPP, September 18, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/2019-income-rent-gap-underscores-need-for-rental-assistance-census-data-show.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “America’s Rental Housing 2020,” Appendix Table W-2, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020. “Working” is defined here as having been employed for at least one week during the prior 12 months.

Will Fischer, Douglas Rice, and Alicia Mazzara, “Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families,” CBPP, December 5, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-rental-assistance-reduces-hardship-and-provides-platform-to-expand.

Sandra J. Newman and C. Scott Holupka, “Housing affordability and investments in children,” Journal of Housing Economics, June 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1051137713000600.

Fischer, Rice, and Mazzara, op. cit.

Sophie Collyer et al., “Housing Vouchers and Tax Credits: Pairing the Proposals to Transform Section 8 with Expansions to the EITC and Child Tax Credit Could Cut the National Poverty Rate by Half,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, October 7, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/5f7dd00e12dfe51e169a7e83/1602080783936/Housing-Vouchers-Proposal-Poverty-Impacts-CPSP-2020.pdf.

Will Fischer, Sonya Acosta, and Erik Gartland, “More Housing Vouchers: Most Important Step to Help More People Afford Stable Homes,” CBPP, May 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/more-housing-vouchers-most-important-step-to-help-more-people-afford-stable-homes.

Sonya Acosta is a Policy Analyst with the Housing Policy team. Prior to coming to the Center, she worked on disaster recovery, Native housing, appropriations, and benefits cuts at the National Low Income Housing Coalition. She also worked at several fair housing organizations in the Chicago area and completed two terms of AmeriCorps service.

Acosta holds a B.A in history and international studies from the University of New Mexico and a Master of Science in Public Policy and Management from Carnegie Mellon University.

Erik Gartland is a Research Associate in the Housing Division. Prior to joining the Center, he was a Data Management Analyst at the Wisconsin Department of Justice, where he created a data catalog and promoted effective data management policies. He has also worked at the Institute for Community Alliances, the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families, and Epic Systems.

Gartland holds a B.A. in economics and political science from St. Olaf College and a Master of Public Affairs from the University of Wisconsin.

Join with the Economic Policy Institute to build an economy that works for everyone

We need your help in order to continue our work on behalf of hard-working Americans. Our donors value our high-quality research, reputation for truth-telling, and practical policy solutions. Your tax-deductible gift to EPI makes you an important partner in providing this critical public service.

Spread the word