On Google Earth, they look like a bumpy rash on the landscape. Zoom in closer and the bumps emerge as mounds in the desert sand, thousands of them in tight rows. Each of these mounds is an unmarked grave and a reminder of a terrible slaughter. And it is between these rows, where his ancestors lie, that artist and activist Laidlaw Peringanda performs a painful duty.

He comes to care for the graves that hug the outskirts of Swakopmund in Namibia. The worst aspect of the job is when the sea wind has blown and eroded some of the mounds, exposing the bones and skulls of his ancestors.

“It is not easy,” says Peringanda. “To do this you need a strong heart.”

The graveyard is the final resting place of thousands of Herero who were the victims of the 20th century’s first genocide. They died in the concentration camps the Germans erected around Swakopmund.

No one knows exactly how many Ovaherero and Nama died between 1904 and 1908. As many as 80% of the Ovaherero might have died, while the Nama may have lost half their population.

For decades, the descendants of those killed in what began as an uprising have called for Germany to recognise that the wholesale killings were genocide and pay reparation.

‘Not enough’

The German government officially called the events a genocide in 2015, but refused to pay reparation. Negotiations have been ongoing since then, but news broke in mid-May that the Namibian and German governments had reached a financial agreement. Germany is to provide financial aid worth €1.1 billion (about R18 billion) over 30 years.

The full details of this aid package are yet to be revealed, but officials in Berlin said funding would go towards projects relating to land reform, rural infrastructure, water supply and training. Affected communities are to be involved and will benefit from these projects.

The Namibian government said the agreement was “a step in the right direction”. But some descendants say it’s not enough.

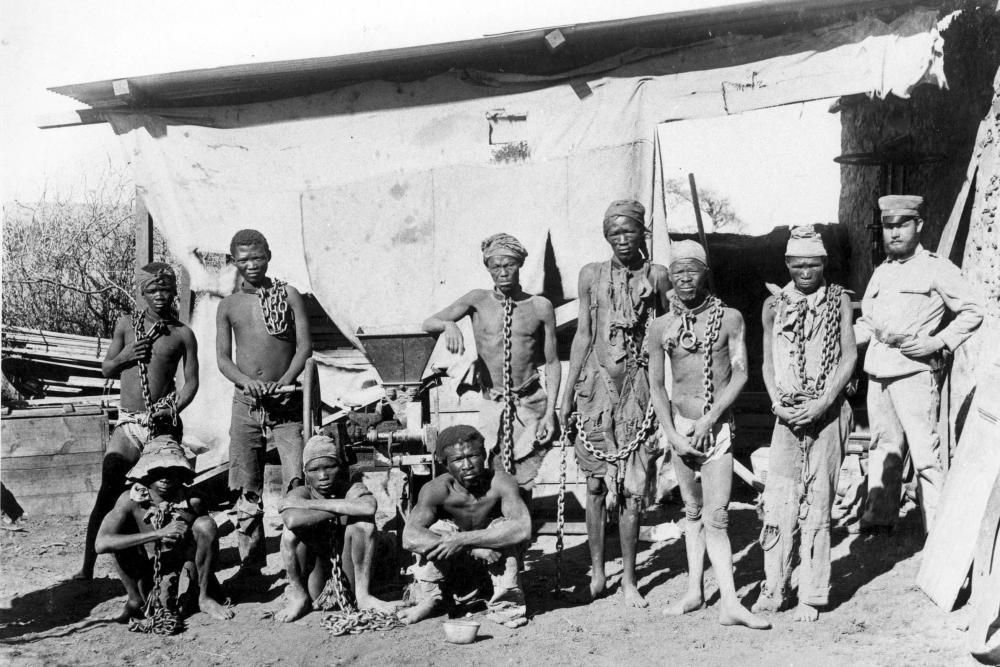

Circa 1904-1908: A soldier said to be German oversees Namibian prisoners of war. The German Historical Museum put on the exhibition Namibia-Germany: A Shared/Divided History in 2004-2005. (Photograph by Handout/ National Archives of Namibia/ AFP)

“We see this as an insult,” says Nandiuasora Mazeingo, the chairperson of the Ovaherero Genocide Foundation. “The Namibian government was only accorded the role of a facilitator in that process, and we have been excluded from the agreement.”

An angry Mazeingo adds that the amount offered is equivalent to the annual budget of Namibia’s education department. “And this is what they are offering for killing 80% of my people, and 50% of the Nama. They have looted our country, and their children still sit on our land.”

He says the Nama and Ovaherero should be allowed to spend the money how they wish.

The ramifications of reparation

The genocide started as a revolt by the Ovaherero and the Nama. General Lothar von Trotha was sent to then German South West Africa in 1904 to suppress the uprising.

He is said to have given what has become known as the extermination order: “Any Herero found inside the German frontier, with or without a gun or cattle, will be executed. I shall spare neither women nor children.” The troops under his command were brutal.

Those not shot were forced into the desert to die of hunger and thirst, or were rounded up and placed in concentration camps. German colonists seized and settled on their land.

“Scholars like myself and others say that to understand how the atrocities in the Nazi regime culminated in a singular form of extermination strategy, you need to revisit the seeds planted in German’s colonial days,” says Henning Melber, a Namibian political activist. “It does not mean there is a causal direct, but there is a linkage between the German colonial atrocities and what happened 35 years later, in Germany and in the expansion to Eastern Europe.”

Melber explains that the problem Germany has faced is that it has wanted to avoid at all costs paying anything that is defined as reparation.

“There were a number of court cases related to atrocities committed by German soldiers during World War II in Italy, in Greece, in Poland and other Eastern European countries, and local courts in these countries ruled that Germany must pay reparation to the descendants of the victims who were executed.

The German government has always refused to acknowledge the rulings, arguing that the government cannot be held accountable for atrocities committed by individual soldiers.”

To admit to paying reparation, the families of those World War II victims would be in line to be compensated, as would those in the former German colonies that experienced atrocities at the hands of their colonial masters.

Melber says it goes even further. “I’m pretty sure that on a European level behind closed doors in the EU, the foreign ministries of other former colonial powers have told the Germans in no uncertain terms to be aware of what they negotiate. Because if they create a precedent as a former colonial power to pay reparations for historical injustices, that will get really expensive for the UK, for France, for Belgium.”

‘Namibia has failed Africa’

Like Mazeingo, Melber says what Germany is offering is not enough. “The communities living in the eastern-central and southern regions of Namibia are on a daily basis confronted with the fences of the white farmers. And it is this land that their ancestors were expropriated off. So, colonialism is not over.”

He said the €1.1 billion Germany is giving is equivalent to what the European country has given Namibia over the past 30 years in development cooperation.

Representatives of the Nama and Ovaherero have vowed to continue to oppose the agreement. They plan not to welcome German foreign minister Heiko Maas when he comes to Namibia to ratify the deal.

The Nama Traditional Leaders Association and the Ovaherero Genocide Foundation have pointed out that the Herero and Nama communities who fled the genocide and settled in Botswana and South Africa are not included in the agreement. “Namibia has failed Africa in not holding a former European genocidal colonial power to account,” they said in a joint statement.

They are planning their next move and have gone online, where petitions are being drawn up and signed. A change.org petition calls on reparation to be paid to the descendants of the victims of the genocide rather than the Namibian government, that Germany accept full responsibility for the killings and that the term reconciliation agreement be replaced by reparation agreement.

Oral history

Not far from the cemetery in Swakopmund is the Democratic Resettlement Community, or the DRC shack settlement. Here, many of the descendants of the victims of the genocide live landless and without drinkable water.

Older generations recounting the genocide has kept the stories of killing, rape and hunger alive for some DRC residents. For a long time, these stories never reached a wider audience. But this is changing.

Former liberation fighter Uazuvara Katjivena published his book, Mama Penee: Transcending the Genocide, in 2020. It narrates the story of his grandmother, who witnessed the killing of her parents as an 11-year-old. After being forced to survive in the desert, Germans captured her and passed her from family to family. They gave her the name Petronella, which means little rock, because she was so stubborn.

“If you’re talking about reconciliation, you first have to tell it how it was, and that has really never happened in Namibia. Not in respect to the genocide, or more recently the Namibian liberation struggle,” says anthropologist Heike Becker, who has written extensively about Namibia.

Peringanda also grew up hearing stories about the genocide from his family. “My great-grandmother told me about the history of the concentration camp. I was eight years old and I thought it was just a fairy tale or something. But when I went there in 2015 and I saw the vastness of the graveyard for the first time, I cried.”

Peringanda now guides people on a genocide tour of Swakopmund. Sometimes, when German tourists visit the cemetery and see those burial mounds for the first time, like him, they cry. Many, he has discovered, have never heard of the genocide.

“You see, the descendants of the victims and perpetrators are experiencing transgenerational trauma. So we need to heal the wounds of the past in order to have a better future,” says Peringanda.

Shaun Smillie is a freelance journalist based in Johannesburg. He has written for a number of local publications on a variety of topics, but has a penchant for writing about science, history, archaeology and crime.

New Frame is a not-for-profit, social justice media publication based in Johannesburg, South Africa. We chase quality, not clicks.

Spread the word