Bigler's Gambit: How the California Gold Fields Gave Rise to Global Anti-Chinese Politics

John Bigler was not a gold miner, but he was part of the forty-niner generation. He was one of many Americans who went to California to make his fortune by doing business with gold miners. In that sense he was also a gold seeker.

Bigler had trained as a lawyer but when he arrived in Sacramento from Ohio in 1849 there were no law positions. Bigler chopped wood and unloaded freight at river docks and then decided to try his hand at politics. Why not? Everything was new, wide open. Bigler won his first race for state assembly in California Territory’s first general election. He rose quickly in state politics and 1851 he received his party’s nomination for governor and won that election.

When Bigler took office in January 1852, California was swirling with debate over how to best harness the energies of the gold rush and develop the state’s economy, especially in agriculture. Some imagined that California would anchor a Pacific coast empire, even one that would stretch from “Alaska to Chili.”

Some boosters, like California’s pro-slavery U.S. senator William Gwin, advocated for the use of enslaved Blacks and native Hawaiians. Others envisioned the use of Chinese labor. Chinese had begun emigrating to California in 1850 as independent gold-mining prospectors and merchants. To some observers, the Chinese appeared to be a potential labor supply for the state. At the time there was no railroad connection over the Rockies, making the transportation of white labor from the east prohibitively expensive. The Presbyterian Reverend William Speer, a former China missionary who established the first Christian mission in San Francisco’s budding Chinese quarter, imagined Chinese labor in California as part of a grand vision of Sino-American unity.

Others advocated for the use of Chinese indentured labor. In February 1852, George Tingley and Archibald Peachy introduced “cooley bills” into the state legislature. Tingley and Peachy were no doubt aware of the “coolie trade” that was supplying indentured contract workers from China and India to Caribbean plantation colonies in the wake of the abolition of slavery. Now that the gold rush had opened transpacific trade, Chinese were also going to Hawai’i as contracted sugar plantation workers, a development that encouraged the ambitions of men like Gwin, Tingley, and Peachy. The bills, aimed principally at agricultural workers, proposed that the state guarantee labor contracts made abroad between Americans and foreign workers for work in the United States. Peachy’s bill set a minimum contract at five years and Tingley’s at ten years, which exceeded anything in the Caribbean or elsewhere, and a minimum wage of fifty dollars a year, a pathetically low amount.

Opponents of the California coolie bills were not necessarily against Chinese immigration in general. The Daily Alta California supported free immigration, which in principle it believed applied to all, regardless of origin. The Alta optimistically predicted that California’s immigrants would in time “vote at the same polls, study at the same schools and bow to the same Altar as our own countrymen”—including the “China Boys,” the “Don from Santa Fe and the Kanaker from Hawaii.” The Alta’s liberality bespoke the Free Soil politics that came from the antebellum North and that in this case assumed a multiracial Pacific perspective. By the same token, the Alta opposed bringing any system of servitude to California, and therefore it opposed the coolie bills before the legislature.

The coolie bills failed to pass the state legislature. But the distinction made by the Alta between free and indentured immigrants quickly blurred. Bigler himself was largely to blame for the obfuscation. On April 23 Bigler issued a special message to the legislature on the Chinese Question. Bigler raised alarm over the “present wholesale importation to this country of immigrants from the Asiatic quarter of the globe,” in particular that “class of Asiatics known as “Coolies.” He declared that nearly all were being hired by “Chinese masters” to mine for gold at pitiable wages, while their families in China were held hostage for the faithful performance of their contracts. Bigler called upon the legislature to impose heavy taxes on the Chinese to “check the present system of indiscriminate and unlimited Asiatic immigration,” and for a law barring Chinese contract labor from California mines.

What was Bigler’s intention? The coolie bills were “at last dead—very dead, indeed,” according to the Alta. Chinese in California were neither contracted nor indentured labor. But Bigler knew that whites were uneasy about the growing Chinese population, which had nearly doubled in the past year. Bigler saw political potential in the Chinese Question. He had won his first election in 1851 by fewer than five hundred votes. With his reelection in 1853 uncertain, he used the Chinese Question to excite the populous mining districts to his side. By tarring all Chinese miners as “coolies,” Bigler found a racial trope that compared Chinese to black slaves, the antithesis of free labor, and thereby cast them as a threat to white miners’ independence.

Bigler’s message was published in the Alta and also circulated on “small sheets of paper and sent everywhere through the mines.” As he had intended, Bigler roused the white mining population. Miners gathered in local assemblies and passed resolutions banning Chinese from mining in their districts. In May, at a meeting held in Columbia, Tuolumne County, miners echoed Bigler’s charges. They railed against those who would “flood the state with degraded Asiatics, and fasten, without sanction of law, the system of peonage on our social organization,” and they voted to exclude Chinese from mining in their district. Other meetings offered no reasons but simply bade the Chinese to leave, or to “vamose the ranche .” Sometimes they used violence to push Chinese off their claims.

Bigler was the first politician to ride the Chinese Question to elected office. He won reelection in September 1853, with 51 percent of the vote. Bigler’s success in tarring the Chinese as a “coolie race” gave California politicians a convenient trope that could be trotted out whenever conditions called for a racial scapegoat. But more than a political tool, anticoolieism became a kind of protean racism among whites on the Pacific coast.

*

Tong K. Achick (Tang Tinggui) and Yuan Sheng were not afraid of John Bigler. Like Bigler and other white elites, they were not miners but businessmen and political leaders. The two men were hailed from the region in what is now Zhongshan county in Guangdong province. They were leaders of the Yeong Wo Association, educated men, successful merchants, and fluent in English.

Within days of Bigler’s special message, Tong K. Achick wrote a letter to the governor. He signed it along with Hab Wa, a merchant who had recently arrived on the Challenge. In their letter, Tong Achick and Hab Wa attested that, contrary to Bigler’s claims, none of the five hundred Chinese passengers on the Challenge were coolies. They explained that Chinese in California included laborers as well as tradesmen, mechanics, gentry, and teachers; “none are ‘Coolies’ if by that word you mean bound men or contract slaves.” They stated emphatically, “The poor Chinaman does not come here as a slave. He comes because of his desire for independence.”

In addition, Hab Wa and Tong Achick astutely argued that there was a positive relationship between migration and trade. Migration begat commerce, which contributed to the “general wealth of the world.” Whereas Bigler saw only hundreds of coolies disembarking from the Challenge and other ships, Hab Wa and Tong Achick saw both people and freight. Knowing Americans’ interest in business, they warned, “If you want to check immigration from Asia, you will have to do it by checking Asiatic commerce.”

Yuan Sheng also spoke out against Bigler’s message. In early May he wrote, under the name Norman Assing, to the governor and sent a copy to the Alta. He announced himself as “a Chinaman, a republican, and a lover of free institutions; much attached to the principles of the Government of the United States.” The letter insisted, “We are not the degraded race you would make us. We came amongst you as mechanics or traders, and following every honorable business of life.” Yuan used his own case as a naturalized citizen to refute Bigler’s claim that no Chinese had ever made the United States his domicile or applied for naturalization.

Bigler did nothing to mitigate the racism that he had stirred up in the gold districts. Tong Achick sent a second letter a month later, filled with pain. “At many places they [the Chinese] have been driven away from their work and deprived of their claims,” he wrote. Some were “suffering even for want of food and . . . have fallen into utter despair. We are informed that grown men may sometimes be seen, sitting down alone in the wildest places, weeping like children.”

Tong pledged that the Chinese would “cheerfully” and “without complaint” pay the foreign miner’s tax of three dollars a month, which the legislature had imposed at Bigler’s urging. Tong understood that a license, even more explicitly than a tax, embodied a commitment on the part of the government that “when we have bought this right [to mine] we shall enjoy it.” He asked, “Will you bid [the tax collector] to tell all the people that we are then under your protection, and that they must not disturb us?”

The foreign miners tax of 1852 was California’s second such tax. The first, passed in May 1850, had aimed to punish foreign miners, especially Mexicans and Chileans, who were among the most skilled and hence the most competitive, as well as Europeans. (Chinese were not then the focus, as few had yet arrived on the goldfields.) The tax aroused angry opposition and the legislature repealed it in 1851.

Notwithstanding the disaster of the first tax, the legislature again used its power to tax to attack the Chinese. The new foreign miners tax was set at three dollars a month. Although it did not specify any particular group, it was understood in the legislature that “the bill is directed especially at Chinamen, South Sea Islanders , etc. and is not intended to apply to Europeans.”

Although Chinese miners dutifully paid the tax, harassment and violence against them continued. At least some whites, it seemed, were not satisfied with punishing Chinese with an onerous tax but wanted their wholesale removal and exclusion from the goldfields and from the state.

In 1853 Tong Achick led a group of Chinese to meet with legislature’s Committee on Mines and Mining Interests that was considering amendments to the foreign mines tax. Tong suggested that the revenue from the tax be shared between the state and the various counties where it was collected. Such an arrangement, he explained, might provide an incentive for local communities to tolerate and accept the Chinese. Possibly, over time, they might become friends. In fact, the Chinese would be willing to pay a higher tax to offset reduced funds to the state.

Tong Achick and his fellow leaders displayed a sophisticated grasp of the stakes in the foreign miners tax. Their eagerness to embrace the tax, even an increased one, was not a capitulation to racism. They understood that racist fever against Chinese still ran high, and they sought to counter it by appealing to the economic interests of local communities in the form of shared revenue. The Chinese had already invested as much as $2 million in businesses and property in California. If the Chinese could prevent wholesale exclusion, if they could establish and hold some ground, even if marginal, they could survive and persist, and perhaps eventually prosper, on Gold Mountain.

Amendments to the foreign miners tax passed by the legislature in 1853 increased the license fee to four dollars per month and designated half of the revenue to go to the county where it was collected. The revenue generated by the tax was considerable: $100,000 to the state and $85,000 to the major mining counties in 1854 and as high as $185,000 to the state and nearly as much to the counties in 1856.

As Tong Achick predicted, the income from the foreign miners tax underwrote a grudging toleration of the Chinese on the goldfields. As well, many Chinese who had been chased away simply returned to their claims, and white miners did not have the energy to be constantly fighting them. This is not to say that that harassment and violence ended. Unscrupulous whites posed as tax collectors to take money from Chinese; in 1861 Chinese merchant leaders reported that during the 1850s whites had murdered at least eighty-eight Chinese, including eleven killed by tax collectors. Only two men were convicted and hanged.

Still, an uneasy coexistence settled on the goldfields, marked by both suspicion and transaction, and by both occasional violence and occasional cooperation. In Yuba County, for example, white miners were not successful at eliminating the Chinese from their river claims. By 1860 Chinese in Marysville were working as garden farmers, cooks, servants, and laundry operators, including a few located in white neighborhoods. Through experience, Chinese also became wiser in their dealings with white miners. H. B. Lansing, who mined in Calaveras County, frequently sold, or tried to sell, his claims to Chinese. In 1855 he lamented in his diary, “Tried to sell a claim to some Chinese but could not come it. They are getting entirely too sharp for soft snaps.”

If by the 1860s race relations on the gold fields seemed calmer, the Chinese Question took on new life in San Francisco in the 1870s. The completion of transcontinenal railroad in 1869 had not brought unalloyed prosperity to the Pacific coast. Workers in California faced economic competition from new migrants and mass manufactured goods from the east coast, as well as the long tail of the depression of the mid-1870s. The Chinese Question, born during the gold rush years, offered a ready nativist playbook that could be adapted to new conditions: racist theories appealed to grievances among sectors of the population and weaponized by politicians for partisan gain. The Chinese Question tore San Francisco asunder with violent agitation, swept state politics, and relentlessly drove national politics. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, thanks to an alliance of the nation’s two bastions of white supremacy, the south and the west.

*

The Chinese exclusion policy of the United States inspired white supremacists in the British settler colonies. There had been opposition to Chinese gold seekers in Australia but anti-Chinese sentiment on the goldfields was much more inchoate than in the California. European gold seekers did not theorize Chinese as coolies because there was no proximate association with enslaved Black labor. But anti-coolieism gained force later in the nineteenth century among urban workingmen’s movements, which borrowed freely from the American example. As in the U.S., the Chinese Question was a weapon of emergent racial nationalism. In South Africa it was a political flashpoint that served to mitigate tensions between the British and Afrikaner descended populations, towards resolution of the “Native Question” (that is, how whites would rule over the African majority), which loomed over all else. In both Australia and South Africa, the Chinese Question served the movements for federation in 1901 and 1910 respectively. As British “dominions” they exercised maximum political autonomy within the British Empire, setting exclusionary race policies that were not possible in the metropole. London acquiesced to them in order to protect imperial interests, not least its control over two-thirds of the world’s gold output.

The Chinese Question and Chinese exclusion policies thus circumnavigated the Anglo-American world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It did not emerge fully formed, like Athena from Zeus’s head. Rather, it grew in local soils and shifted and evolved as it crossed the Pacific world and supported the consolidation of British and American power over global emigration and trade.

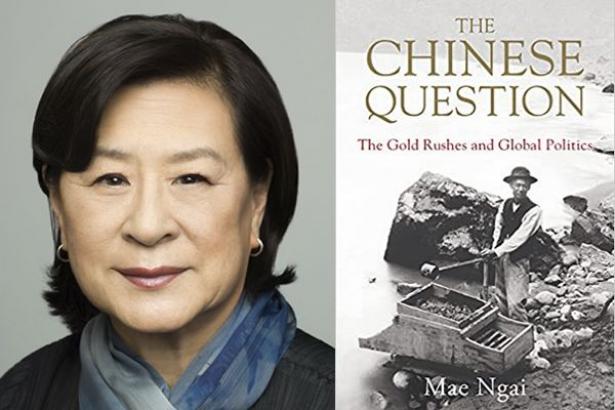

Mae Ngai is the Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies, Professor of History, and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race at Columbia University. Her latest book, The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics is published this month by W.W. Norton.

History News Network depends on the generosity of its community of readers. If you enjoy HNN and value our work to put the news in historical perspective, please consider making a donation today!

Spread the word