labor Confronted With The Holiday Rush, Understaffing, and Omicron, Retail Workers are Organizing and Speaking Out

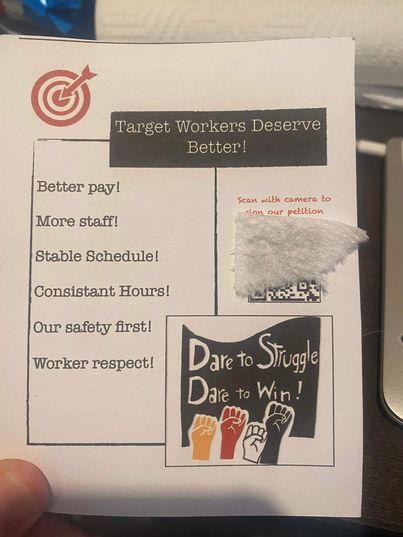

The week before Christmas, Indianapolis Target employee Andrew Stacy was spreading the word about a unionizing effort at their store. The busy holiday season—and new anxieties raised by the recently emerged Omicron variant of COVID-19—was no reason for them to wait until the New Year. The conditions at the store had become so dire around the holidays that organizing seemed even more urgent.

“I’ve had to go into superspeed, escalating everything that I’m having to do just because the fourth quarter has been so difficult,” said Stacy, 32, member of the workers’ group Target Workers Unite.

Staffing is half of what it typically has been during the holidays, with fewer seasonal workers hired to take on shifts, Stacy told Prism. Cashiers aren’t getting adequate breaks, if any at all. And the standard $15-an-hour wages Target set in 2020 aren’t enough to live on—in a petition Stacy drafted, one of the key demands is for a minimum $17 per hour. Target recently announced it is offering that wage on weekends during the holidays, but Target workers note wages aren’t keeping up with inflation.

“Everybody is at their wits’ end with it,” Stacy said. Working at Target has “become a much more soul-sucking and joyless experience than it has ever been.”

But when Stacy and their coworker were posting the flyers in the break room and distributing them, they were caught. Management confiscated the flyers and human resources held one-on-one meetings with workers about working conditions and higher-ups at the location—a move that Stacy saw as an illegal effort to shut down organizing and find out more about the union activity. In response, they filed a National Labor Review Board complaint on Dec. 15. Prism has reached out to Target for comment on the concerns raised by workers as well as the complaint.

Workers’ struggles at Target are just one example of what retail employees are facing this holiday season. About 15 million people work in retail in the U.S.—but Black and Latinx retail workers are more likely to be living in or near poverty, according to a 2015 policy paper published by liberal think tank Demos. Cashiers specifically, who are among the lowest paid workers in the industry, are disproportionately Black and Latinx. Among retail workers with jobs as cashiers, salespersons, or first-line supervisors, about 56.5% were women, according to a 2020 Census Bureau report. The holidays are notoriously difficult for retail workers, starting with Black Friday. Since the pandemic began, hundreds of thousands of retail workers have quit in what’s been called the “Great Resignation,” and the skeleton crew of retail workers left behind have to deal with impatient customers and management pushing them to do more with less, according to retail workers across the country whom Prism interviewed. They said supply chain problems create a mismatch between actual inventory and what’s listed online and maskless customers remain a source of frustration. And now, amid a new wave of coronavirus cases, they face newfound uncertainties.

For an Old Navy employee in New York City, it seemed in-store customers had returned for the holidays in full force.

“The store hasn’t been this crowded in a long time,” said the employee, who’s been working at the company for over a decade. She requested anonymity because she wasn’t authorized to speak to a journalist.

“I’m used to it from before [the pandemic],” said the woman. “Now with COVID, it’s a little bit more nerve-wracking, because not everybody wears their mask.”

“It’s a little bit more intense,” she said. The worker, who is Black, worries about catching COVID-19 and not receiving the same treatment as others if she needs to see a doctor, given the prevalence of racial discrimination in medical care. She works full time, so she has some paid time off, but it is still stressful. “You have to be more careful than before.”

“I had a customer get upset with me because I told him to put his mask on today,” she said, and customers have complained about long lines at checkout. She also worries about shoplifters lashing out if she confronts them.

Understaffing prompted by newcomers calling out of work or quitting their jobs has made the workload feel higher, said the employee. She believes the shortages are due to the minimum wage pay—$15 an hour—which prompts workers to jump ship for jobs that pay more. For now, she sticks around because she can’t afford to quit and she’s not so sure she could find a better job in retail—something she’s become passionate about despite the shortcomings of the industry for workers.

An Old Navy spokesperson said the company, owned by Gap Inc., is “continuing to evolve our strategies to attract and retain talent.”

Meanwhile, the National Retail Foundation says retail sales continue to rise, in spite of inflation, Omicron, and supply challenges. The industry group expected 148 million Americans to shop last weekend on “Super Saturday,” the Saturday before Christmas. About seven in 10 of those Americans were expected to shop either in-store or both online and in-store, according to its estimates.

Jose Palma, a two-year H&M employee in New York City, said the Manhattan location he works at has been “super crowded” this season, and he feels there aren’t enough workers to “support what the business really needs.”

Palma recently faced a maskless customer angry about not receiving a sale and another about the store’s return policy. “Coming in with that attitude and then also still not respecting the social awareness of Omicron, especially in New York, to me, is super disrespectful,” said Palma, a 23-year-old nursing student. New York City’s health department data shows daily new cases have nearly tripled in the last week, with Omicron making up over 90% of current cases in the Health and Human Services region that includes New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

Palma is working both Christmas Eve and Christmas Day for an extra four hours pay at $16.32 an hour—the current rate he receives as a part-timer. In Manhattan, the living wage for a single adult without children is $21.77, according to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology researcher’s estimate, whose research factored in bare minimum needs in the U.S., not leisure, entertainment, or holidays.

Gloria Song, a personal shopper at a Walmart in Maryland, said employees have had to pick up shifts on days off or stay two or three hours late as a result of understaffing.

“We have had a lot of people quit mainly due to the crazy hours or management,” said Song, 31, a member of the retail workers’ advocacy group United for Respect. “The pay has to do with a lot of it too.”

Song feels this holiday season has less panic in the air in her department where she takes online orders and packages them; customers are accustomed to online shopping orders and social distancing. But chronic understaffing ultimately forced her to switch from a managerial role to a personal shopper because of unmeetable expectations.

“They kept telling me, ‘Oh we’re working on getting new people, we’re working on it,’” Song said. “It shut down my confidence. I’m just like, ‘You guys are my managers. You’re supposed to help me out.’”

A Walmart spokesperson, Jimmy Carter, said over 150,000 associates have been hired to ensure stores are fully staffed for the holidays. “This specific store is currently fully staffed,” Carter added. “Many of our associates like to swap shifts with each other and/or pick up extra hours, so we offer those opportunities to anyone who is interested.”

H&M did not respond to requests for comment.

In northeastern Ohio, 24-year-old grocery store worker, Ellie, said management is offering at least $15 an hour to entice employees during the holiday season. Just last summer, she was offered $13.50 an hour to start.

“You can see the difference in the pressure was in terms of having to hire to be ready for the holidays,” said Ellie, who requested anonymity because she is in a non-union role.

Still, she said, “it’s very about the comfort of the customer and not the worker.”

Sydney Pereira is a journalist based in Brooklyn. She covers the intersection between social justice and health, labor, and climate change. Her work has been published in Gothamist/WNYC, Newsweek, Patch, The Miami Herald, and others.

Prism is a national nonprofit news outlet run by women of color that centers the people, places, and issues currently underreported by national media. We’re committed to producing the kind of journalism that treats Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), women, the LGBTQ+ community, and other invisibilized groups as the experts on our own lived experiences, our resilience, and our fights for justice.

Readers like you can play a key role in keeping our newsroom strong. Your tax-deductible contribution helps Prism ensure that journalism accurately reflects this current political moment and beyond. Donate: https://secure.actblue.com/donate/prism

Spread the word