‘A Rosetta Stone’: Australian Fossil Site Is a Vivid Window into 15M-Year-Old Rainforest

The Australian paleontologist Matthew McCurry was digging for Jurassic fossils when a farmer dropped by with news of something he’d seen in his paddock – a fossilised leaf in a piece of hard brown rock.

Fossil leaves are not usually anything to write home about, but the spot was close, so McCurry and his colleague Michael Frese went to take a look.

What they found in that dusty paddock near the New South Wales town of Gulgong five years ago has had paleontologists – at least those few who have known the secret – in awe.

Encased in the rocks are the inhabitants of a rainforest that existed in that now dry and arid spot about 15m years ago.

“There’s a whole ecosystem preserved,” says McCurry, curator of paleontology at the Australian Museum and a lecturer at the University of New South Wales.

As their hammers split the iron-rich rocks, thousands of fossils have been revealed – from flowering plants to fruits and seeds, insects, spiders, pollen and fish. There will be scores of new species.

The research team look for insect fossils at the site; on their first visit, McCurry and Frese found tiny aquatic insects preserved in the rock. Photograph: Salty Dingo/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

A fossilised leaf found in the iron-rich rocks of the site. The huge array of leaf fossils has allowed the team to estimate the climate of the area. Photograph: Salty Dingo/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

McCurry and his colleagues revealed the site, and their initial findings, in the journal Science Advances on Saturday Australian time.

“Paleontologists around the world will drool when they see this paper,” said Prof John Long, a famed fossil hunter from Flinders University who got a sneak peek at some of the fossils a year ago.

Such an array of specimens in one spot has allowed the Australian scientists to build an incredibly detailed picture of a little-known ecosystem from a period known as the mid-Miocene – a time just before the continent dried out to be what it is today.

As well as the huge number of different specimens at the site – known as McGraths Flat – it is the fossils’ immaculate preservation that is delivering an unprecedented depth of information.

Under a microscope, there is detail down to below a micron in width (a spider’s thread is about three microns).

The breathing apparatus of spiders and the contents of fish stomachs are visible. The cells that can reveal the original colour of a feather have been preserved. A sawfly was frozen in time with dozens of pollen grains attached to its head.

‘You have complete organisms ... soft tissue ... cellular preservation. There’s a spider with its breathing system beautifully preserved.’ Photograph: Michael Frese/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

Since that first visit, McCurry and his colleagues have unearthed a treasure trove of fossils. When the rocks are broken apart, they tend to split the fossilised remains in half like an instant autopsy, revealing internal organs and tissues.

Fish stomachs are so well preserved McCurry says they can see what that fish ate – about 15m years ago – in the moments before its demise.

“We can see the food in the stomach, like a dragonfly wing. But commonly, it’s insect larvae,” he says.

Long saw some of the fossils last year when he visited McCurry at the Australian Museum.

“Fossils are often preserved as bits and pieces or fragments. Occasionally you might get a whole organism. But this is truly exceptional preservation,” he says.

“You have complete organisms ... soft tissue ... cellular preservation. There’s a spider with its breathing system beautifully preserved. It’s a Xanadu.

“There’s all the diversity with a great range of organisms from fungi to plants and fish, and also you have their interaction. There’s evidence of behaviour. It has all the attributes of a world-class fossil deposit, of which we have very, very few in Australia.”

“It’s a bit of a Rosetta Stone of the full ecology of this middle Miocene environment. We have no other window into that period that tells us what that part of Australia was like.”

Fortunate fossils

New fossil sites are rare finds, and this one was almost missed. McCurry admits he drove past it at least once, oblivious to what was there.

On his first visit with Frese they found rocks rich in iron, unusually hard to split, and of a type not known for preserving fossils.

But immediately, the pair found what they thought were aquatic insects. Using a microscope Frese had in his car, they could see tiny midges preserved. “That’s when we realised how special the fossils were,” McCurry says.

Associate professor Michael Frese, who has been examining the fossils for several years, says he is blown away by their detail. Photograph: Salty Dingo/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

Finding fossilised pollen allowed the scientists to accurately date the site.

Little is known about the ecosystems of the mid-Miocene period.

McCurry says there are likely to be “dozens, if not hundreds” of species new to science that have already been collected. The researchers have found probable new species preserved in the rock deposit between 50cm and 80cm thick at a rate of more than one a day. There have been eight field excavations so far.

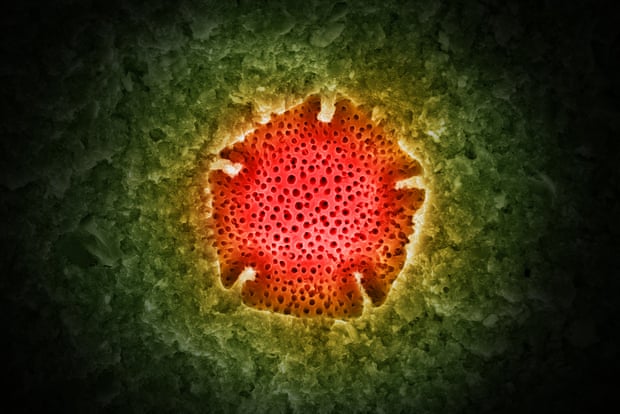

Nothofagidites pollen grain. This artificially coloured scanning electron microscopy image shows a fossil pollen grain (Nothofagadites cf. deminitus), indicating that Nothofagus plants (and mesic rainforests) had a greater geographical range in the Miocene than they have today. Photograph: Michael Frese/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

Even though only two square metres are excavated each time, about 2,000 specimens have been collected. Now follows the painstaking process of checking each one against known records of flora and fauna.

Using analysis of the huge array of plant leaves at the site, the team have even been able to estimate the climate of the area. Warm months were about 26C and cool months as low as 7C.

Almost a metre of rain would have fallen in a month in the wet season – the region’s modern climate is hotter but much drier, with the wettest month averaging just 70mm.

Feather fossil

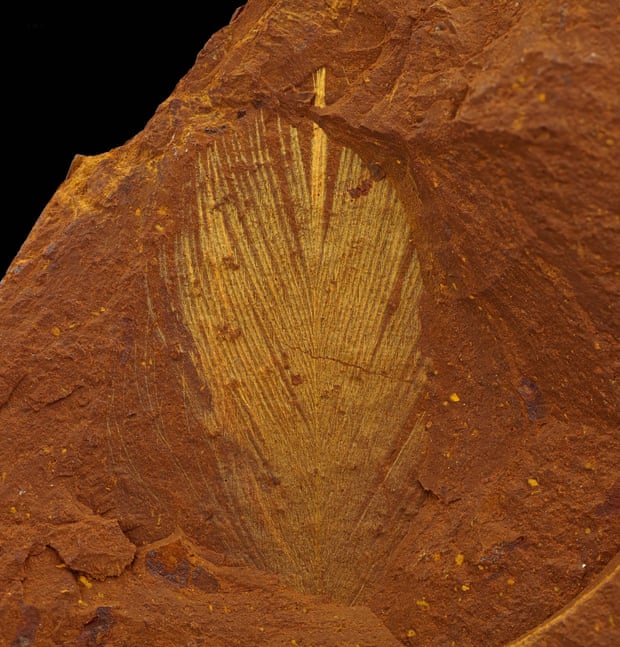

While much of the team go through the vast array of flora and fauna, Dr Jacqueline Nguyen, an expert in the evolution of birds at the Australian Museum, has been mostly fixated on the only evidence found so far of the birds that were in the rainforest. That is, one single fossilised feather about the size of a fingerprint.

Advertisement

“Fossilised feathers are incredibly rare,” she says. “Most are from the Cretaceous, but from the Miocene we only have this one. I’m super excited.”

The fossil feather is so detailed that Nguyen and her colleagues have been able to see the parts of the cells that give the feather its colour. This feather – probably from the bird’s body rather than wing – was likely dark or iridescent.

“Even though it’s just one feather, it’s a tantalising hint at what’s to come. Maybe we’ll find a bird skeleton.”

‘Fossilised feathers are incredibly rare,’ says Dr Jacqueline Nguyen. In this one, roughly the size of a fingerprint, parts of cells that gave the feather its colour have been identified. Photograph: Michael Frese/Courtesy of the Australian Museum

Frese, who is a virologist by training, has been examining the fossils under microscopes for several years.

“I was blown away by the detail,” he says. “I love the way the fossils present themselves. Usually you just see the surface, but here it always splits in half and you see the inside of a spider leg or the inside of pollen.”

The secret to the fossils’ preservation is up for debate, but McCurry thinks it would have happened over hundreds of years rather than in a sudden event.

Iron-rich water, maybe from nearby outcrops, could have flowed into a shallow billabong, periodically deoxygenating the water, killing the organisms or encasing flora and fauna in sediment that turns into the rocks found in the field.

McCurry admits he’s relieved to be able to tell the world about the discovery.

“This has been a marathon,” he says. “It’s a really important find and it’s going to keep us going for a long time.”

Graham Readfearn is an environment reporter for Guardian Australia. Email: graham.readfearn@theguardian.com

An erosion of democratic norms. An escalating climate emergency. Corrosive racial inequality. A crackdown on the right to vote. Rampant pay inequality. America is in the fight of its life. If you can, please make a gift today to fund our reporting in 2022.

For 10 years, the Guardian US has brought an international lens with a focus on justice to its coverage of America. Globally, more than 1.5 million readers, from 180 countries, have recently taken the step to support the Guardian financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent. We couldn’t do this without readers like you.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour. It is reader support that makes our high-impact journalism possible and gives us the energy to keep doing journalism that matters.

Unlike many others, Guardian journalism is available for everyone to read, regardless of what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future.

Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Spread the word