Let’s start from a metaphor. Call human history a mirror. A factual recounting of the past reflects us as we really are. In clean, clear surfaces, we see our faces and our bodies and our beauty and our flaws with precision.

Now imagine the reflection doesn’t match who we imagine ourselves to be, the way we imagine ourselves to look. We can do one of three things. The first is to alter our appearance. The second is to alter our self-image. The third is to throw a blanket over the mirror and pretend it doesn’t exist.

Read the headlines, and it often seems the world has collectively decided to go with option three — taking books out of school curriculums, proposing laws about what can’t be taught in schools, enacting policies that delegitimize or simply obliterate whole populations of people.

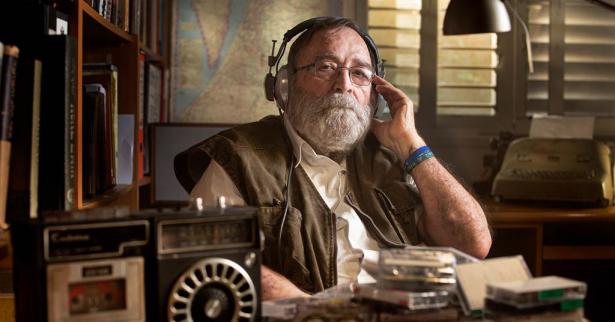

This is hardly new; the old saw that “history is a story told by the winners” is axiomatic for a reason. That’s vividly demonstrated in the new documentary Tantura, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival amid a spate of films about option three. An old man settles into a chair in his backyard and simply tells director Alon Schwarz that he “decided not to think about these things, not to think about them at all.”

“These things” are the events in the Palestinian village of Tantura during the 1948 Arab-Israel War, and specifically on May 23. On that day, around 200 Palestinian Arabs were brutally murdered. Nobody knows exactly how many. They died at the hands of the Alexandroni Brigade, a group of Israeli soldiers. Some historians, with piles of evidence mounting, began to acknowledge a half-century later that what happened there was a massacre.

But the old man — an Alexandroni veteran who was in Tantura that day — joins the country’s official position when he says that these events didn’t happen, weren’t a massacre, and anyhow he decided a long time ago to forget about it. “I stopped,” he tells Schwarz. “And that was it.”

The man in the backyard is one of many elderly Alexandroni veterans interviewed in Tantura, which is a damning and gobsmacking attempt to untangle, with methodical, surgical incisiveness, what really happened on that day in 1948. But while the film is about the horrific events in Tantura, it’s not only about those events. It’s about how national self-image (in this case, Israel’s belief that its military is “the most moral in the world”) can stand in the way of looking in the mirror.

Descendants as well as some eyewitnesses and historians maintain — thanks to the mounting evidence that Tantura clearly lays out — that those civilians were not militants who died as casualties of war, but ordinary people who were brutally massacred. But the state officially maintains that what happened wasn’t a massacre. And that’s so vehemently maintained that when a graduate student, Theodore Katz, submitted a thesis to the University of Haifa in 1998, arguing that civilians in Tantura were massacred and based on extensive oral testimony, he was virtually blackballed after Alexandroni Brigade veterans sued him and won their case (originally, he’d been awarded a score of 97 percent for his thesis). The Israeli Supreme Court refused to hear Katz’s appeal; eventually, his degree was suspended, contingent upon submitting a revised thesis, which Katz refused to do.

Schwarz plays tapes from Katz’s research and marshals an impressive array of sources to make the compelling case that not only did the massacre happen, but many of those involved have managed to tie themselves in mental knots living with that knowledge. So the film works on two levels: one is about the massacre; the other is about the psychology employed not only by perpetrators, but by the powerful forces that back them up.

In this way, it’s reminiscent of (and every bit as heart-wrenching as) Joshua Oppenheimer’s groundbreaking documentaries about mass killings in Indonesia, The Act of Killing (2012) and The Look of Silence (2014). But it would also make a powerful and sobering double feature with Ra’anan Alexandrowicz’s The Viewing Booth (2019), which questions the power that any nonfiction film or footage can wield in getting past our defenses.

It’s always easy to watch a film like Tantura and think this kind of truth suppression is an isolated incident. But if the headlines aren’t enough, other documentaries — many of which premiered at Sundance this year as well, at what like a pivotal moment in the global reckoning with truth — demonstrate with blinding clarity that blankets have been thrown over mirrors all around the world, and they’re causing tremendous harm.

The best of the crop is Margaret Brown’s Descendant, which dives into the history of the Clotilda, the last ship bearing enslaved people to reach American shores in the 1860s, long after the slave trade (though not slavery itself) was outlawed. The ship’s human cargo were sold into slavery in Alabama; the ship itself was destroyed, burned and sunk upriver, to hide the evidence. (The crime of importing slaves, at that time, bore a penalty of death.)

The ship’s existence had been more or less denied, written out of the official record, seemingly thanks to powerful families who still benefit from inherited wealth accumulated in the slavery era. But descendants of the enslaved people have fought hard to establish the Clotilda’s existence, both to understand their own roots better and to prove to the world that that crime actually happened — that that piece of history cannot merely be brushed aside because it makes some people feel bad to remember it.

Descendant’s story has obvious significance for a country that is currently ablaze with battles over whether the truth of slavery and other horrors can be taught with frankness to schoolchildren. In the months prior to the film’s Sundance premiere, a wave of proposed legislation banning books and classroom discussions that deal with the history of racism in America — prompted by a manufactured moral hysteria over “critical race theory” — swept across the country and began to have a chilling effect on classroom teachers. Headlines about school boards pulling books that make white children or parents feel uncomfortable from libraries have become a weekly occurrence.

It is, frankly, terrifying to watch. What Descendant demonstrates is how ignoring the real story — the ship sunk to the bottom of the river by people who find its truths uncomfortable — doesn’t just steal people’s history from them. It impoverishes the future. More than that: without facing the past with courage, exploring it without succumbing to emotional panic, there is no future. Can you understand patterns of urban poverty without facing the historical reality of redlining? Can you fully grasp economic inequality without learning the story?

The past can’t be changed. But if we won’t tell the truth about it, we can’t learn from it. We can’t even understand ourselves. We’re standing before a mirror that’s missing big pieces.

That’s why there’s power to documentaries that confront the erasure of inconvenient facts; the visual and narrative power has a way of shifting minds. Those were in evidence everywhere this year at Sundance. Rory Kennedy’s Downfall: The Case Against Boeing shows how corporate fixation on profit and pleasing Wall Street led to the deaths of hundreds; the company tried to redirect blame and culpability when a known issue with the Boeing 737 Max plane led to two crashes and hundreds of deaths. Similarly, Ramin Bahrani’s engrossing 2nd Chance tells the story of Richard Davis, the inventor of the concealable bulletproof vest, and shows how the company willingly covered up deficiencies in a new model that led to the death of police officers.

Abigail Disney’s The American Dream and Other Fairy Tales exposes the failure of Disney to acknowledge its exploitative hiring practices, instead covering them up with corporate lingo and the magic of its myths. And Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville, USA shows the ways the US military ignored the results of investigations into civil unrest in the 1960s, choosing to fixate on the militarization of the police force.

These are just a sampling; there are plenty more, including The Exiles, which dives into the erasure of the 1989 massacre of protesters in Tiananmen Square by the Chinese government. But Americans don’t find it hard to believe that the Chinese government is covering up history to promote its own nationalistic ends. It remains difficult for many Americans to acknowledge when companies and corporations do the same here.

But the gaps left by inconvenient facts need filling in. And in an image-oriented world, a documentary can have an effect. Certainly films exposing the truth have made an impact on viewers, from Titicut Follies and The Thin Blue Line to Super Size Me and An Inconvenient Truth.

Can a documentary film, on its own, fix the problem? No, of course not. Just making a movie isn’t enough. Just watching it passively isn’t the answer.

The power in a documentary isn’t just from reiterating historical facts, though. It’s in being willing to witness the stories and images and testimonies they tell — to sit with them, to not turn off the TV or close the book or write the law designed to keep some people comfortable. Procession, Robert Greene’s documentary about survivors of childhood abuse at the hands of Catholic priests — abuse strenuously covered up for decades by the powerful — seeks to do more than expose a story that’s been in the headlines for years. Instead, it asks us to live alongside people grappling with the effects of that cover-up.

Procession, Tantura, Descendant — movies like these pull the blanket off the mirror, exposing the ugliness. It’s up to the viewers to do that difficult, painful work. To be willing to look real history square in the eye and accept what it reflects.

It’s only the truth, to paraphrase a wise man, that will set you free.

_____________

Tantura, 2nd Chance, The American Dream and Other Fairy Tales, The Exiles, and Riotsville, USA are awaiting distribution. Descendant and Downfall: The Case Against Boeing will premiere on Netflix later this year. The Act of Killing is streaming on Hulu and available for rental on digital platforms. The Look of Silence is streaming on Amazon Prime and available for rental on digital platforms. The Viewing Booth is available to rent on the film’s website. Titicut Follies is streaming on Kanopy. The Thin Blue Line is streaming on Amazon Prime and available for rental on digital platforms. Super Size Me is streaming for free on Amazon. An Inconvenient Truth is available for rental on digital platforms. Procession is streaming on Netflix.

Spread the word