The parliament of Catalonia, the autonomous region in Spain, sits on the edge of Barcelona’s Old City, in the remains of a fortified citadel constructed by King Philip V to monitor the restive local population. The citadel was built with forced labor from hundreds of Catalans, and its remaining structures and gardens are for many a reminder of oppression. Today, a majority of Catalan parliamentarians support independence for the region, which the Spanish government has deemed unconstitutional. In 2017, as Catalonia prepared for a referendum on independence, Spanish police arrested at least twelve separatist politicians. On the day of the referendum, which received the support of ninety per cent of voters despite low turnout, police raids of polling stations injured hundreds of civilians. Leaders of the independence movement, some of whom live in exile across Europe, now meet in private and communicate through encrypted messaging platforms.

One afternoon last month, Jordi Solé, a pro-independence member of the European Parliament, met a digital-security researcher, Elies Campo, in one of the Catalan parliament’s ornate chambers. Solé, who is forty-five and wore a loose-fitting suit, handed over his cell phone, a silver iPhone 8 Plus. He had been getting suspicious texts and wanted to have the device analyzed. Campo, a soft-spoken thirty-eight-year-old with tousled dark hair, was born and raised in Catalonia and supports independence. He spent years working for WhatsApp and Telegram in San Francisco, but recently moved home. “I feel in a way it’s a kind of duty,” Campo told me. He now works as a fellow at the Citizen Lab, a research group based at the University of Toronto that focusses on high-tech human-rights abuses.

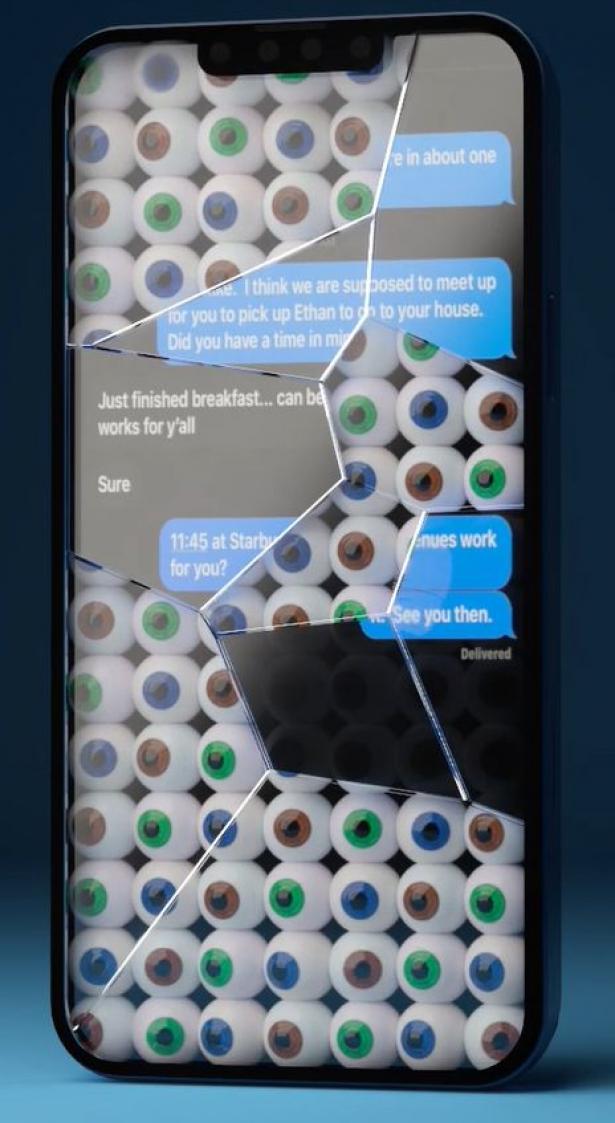

Campo collected records of Solé’s phone’s activity, including crashes it had experienced, then ran specialized software to search for spyware designed to operate invisibly. As they waited, Campo looked through the phone for evidence of attacks that take varied forms: some arrive through WhatsApp or as S.M.S. messages that seem to come from known contacts; some require a click on a link, and others operate with no action from the user. Campo identified an apparent notification from the Spanish government’s social-security agency which used the same format as links to malware that the Citizen Lab had found on other phones. “With this message, we have the proof that at some point you were attacked,” Campo explained. Soon, Solé’s phone vibrated. “This phone tested positive,” the screen read. Campo told Solé, “There’s two confirmed infections,” from June, 2020. “In those days, your device was infected—they took control of it and were on it probably for some hours. Downloading, listening, recording.”

Solé’s phone had been infected with Pegasus, a spyware technology designed by NSO Group, an Israeli firm, which can extract the contents of a phone, giving access to its texts and photographs, or activate its camera and microphone to provide real-time surveillance—exposing, say, confidential meetings. Pegasus is useful for law enforcement seeking criminals, or for authoritarians looking to quash dissent. Solé had been hacked in the weeks before he joined the European Parliament, replacing a colleague who had been imprisoned for pro-independence activities. “There’s been a clear political and judicial persecution of people and elected representatives,” Solé told me, “by using these dirty things, these dirty methodologies.”

In Catalonia, more than sixty phones—owned by Catalan politicians, lawyers, and activists in Spain and across Europe—have been targeted using Pegasus. This is the largest forensically documented cluster of such attacks and infections on record. Among the victims are three members of the European Parliament, including Solé. Catalan politicians believe that the likely perpetrators of the hacking campaign are Spanish officials, and the Citizen Lab’s analysis suggests that the Spanish government has used Pegasus. A former NSO employee confirmed that the company has an account in Spain. (Government agencies did not respond to requests for comment.) The results of the Citizen Lab’s investigation are being disclosed for the first time in this article. I spoke with more than forty of the targeted individuals, and the conversations revealed an atmosphere of paranoia and mistrust. Solé said, “That kind of surveillance in democratic countries and democratic states—I mean, it’s unbelievable.”

[Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today »]

Commercial spyware has grown into an industry estimated to be worth twelve billion dollars. It is largely unregulated and increasingly controversial. In recent years, investigations by the Citizen Lab and Amnesty International have revealed the presence of Pegasus on the phones of politicians, activists, and dissidents under repressive regimes. An analysis by Forensic Architecture, a research group at the University of London, has linked Pegasus to three hundred acts of physical violence. It has been used to target members of Rwanda’s opposition party and journalists exposing corruption in El Salvador. In Mexico, it appeared on the phones of several people close to the reporter Javier Valdez Cárdenas, who was murdered after investigating drug cartels. Around the time that Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia approved the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a longtime critic, Pegasus was allegedly used to monitor phones belonging to Khashoggi’s associates, possibly facilitating the killing, in 2018. (Bin Salman has denied involvement, and NSO said, in a statement, “Our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder.”) Further reporting through a collaboration of news outlets known as the Pegasus Project has reinforced the links between NSO Group and anti-democratic states. But there is evidence that Pegasus is being used in at least forty-five countries, and it and similar tools have been purchased by law-enforcement agencies in the United States and across Europe. Cristin Flynn Goodwin, a Microsoft executive who has led the company’s efforts to fight spyware, told me, “The big, dirty secret is that governments are buying this stuff—not just authoritarian governments but all types of governments.”

NSO Group is perhaps the most successful, controversial, and influential firm in a generation of Israeli startups that have made the country the center of the spyware industry. I first interviewed Shalev Hulio, NSO Group’s C.E.O., in 2019, and since then I have had access to NSO Group’s staff, offices, and technology. The company is in a state of contradiction and crisis. Its programmers speak with pride about the use of their software in criminal investigations—NSO claims that Pegasus is sold only to law-enforcement and intelligence agencies—but also of the illicit thrill of compromising technology platforms. The company has been valued at more than a billion dollars. But now it is contending with debt, battling an array of corporate backers, and, according to industry observers, faltering in its long-standing efforts to sell its products to U.S. law enforcement, in part through an American branch, Westbridge Technologies. It also faces numerous lawsuits in many countries, brought by Meta (formerly Facebook), by Apple, and by individuals who have been hacked by NSO. The company said in its statement that it had been “targeted by a number of politically motivated advocacy organizations, many with well-known anti-Israel biases,” and added that “we have repeatedly cooperated with governmental investigations, where credible allegations merit, and have learned from each of these findings and reports, and improved the safeguards in our technologies.” Hulio told me, “I never imagined in my life that this company would be so famous. . . . I never imagined that we would be so successful.” He paused. “And I never imagined that it would be so controversial.”

Hulio, who is forty, has a lumbering gait and pudgy features. He typically wears loose T-shirts and jeans, with his hair in a utilitarian buzz cut. Last month, I visited him at his duplex in a luxury high-rise in Park Tzameret, the fanciest neighborhood in Tel Aviv. He lives with his three small children and his wife, Avital, who is expecting a fourth. There’s a pool on the upper level of Hulio’s apartment, and downstairs, in the double-height living room, is a custom arcade cabinet stocked with retro games and bearing a cartoon portrait of him, wearing shades, next to the word “Hulio” in large eight-bit font. Avital attends to the children, frequent renovations, and an ever-shifting array of pets: rabbits remain, a parrot does not. The family has a teacup poodle named Marshmallow Rainbow Sprinkle.

Hulio, Omri Lavie, and Niv Karmi founded NSO Group in 2010, creating its name from the first letters of their names and renting space in a converted chicken coop on a kibbutz. The company now has some eight hundred employees, and its technology has become a leading tool of state-sponsored hacking, instrumental in the fight among great powers.

The Citizen Lab’s researchers concluded that, on July 26 and 27, 2020, Pegasus was used to infect a device connected to the network at 10 Downing Street, the office of Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A government official confirmed to me that the network was compromised, without specifying the spyware used. “When we found the No. 10 case, my jaw dropped,” John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at the Citizen Lab, recalled. “We suspect this included the exfiltration of data,” Bill Marczak, another senior researcher there, added. The official told me that the National Cyber Security Centre, a branch of British intelligence, tested several phones at Downing Street, including Johnson’s. It was difficult to conduct a thorough search of phones—“It’s a bloody hard job,” the official said—and the agency was unable to locate the infected device. The nature of any data that may have been taken was never determined.

The Citizen Lab suspects, based on the servers to which the data were transmitted, that the United Arab Emirates was likely behind the hack. “I’d thought that the U.S., U.K., and other top-tier cyber powers were moving slowly on Pegasus because it wasn’t a direct threat to their national security,” Scott-Railton said. “I realized I was mistaken: even the U.K. was underestimating the threat from Pegasus, and had just been spectacularly burned.” The U.A.E. did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and NSO employees told me that the company was unaware of the hack. One of them said, “We hear about every, every phone call that is being hacked over the globe, we get a report immediately”—a statement that contradicts the company’s frequent arguments that it has little insight into its customers’ activities. In its statement, the company added, “Information raised in the inquiry indicates that these allegations are, yet again, false and could not be related to NSO products for technological and contractual reasons.”

According to an analysis by the Citizen Lab, phones connected to the Foreign Office were hacked using Pegasus on at least five occasions, from July, 2020, through June, 2021. The government official confirmed that indications of hacking had been uncovered. According to the Citizen Lab, the destination servers suggested that the attacks were initiated by states including the U.A.E., India, and Cyprus. (Officials in India and Cyprus did not respond to requests for comment.) About a year after the Downing Street hack, a British court revealed that the U.A.E. had used Pegasus to spy on Princess Haya, the ex-wife of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, one of the Emirates. Maktoum was engaged in a custody dispute with Haya, who had fled with their two children to the U.K. Her attorneys, who are British, were also targeted. A source directly involved told me that a whistle-blower contacted NSO to alert it to the cyberattack on Haya. The company enlisted Cherie Blair, the wife of former Prime Minister Tony Blair and an adviser to NSO, to notify Haya’s attorneys. “We alerted everyone in time,” Hulio told me. Soon afterward, the U.A.E. shut down its Pegasus system, and NSO announced that it would prevent its software from targeting U.K. phone numbers, as it has long done for U.S. numbers.

Elsewhere in Europe, Pegasus has filled a need for law-enforcement agencies that previously had limited cyber-intelligence capacity. “Almost all governments in Europe are using our tools,” Hulio told me. A former senior Israeli intelligence official added, “NSO has a monopoly in Europe.” German, Polish, and Hungarian authorities have admitted to using Pegasus. Belgian law enforcement uses it, too, though it won’t admit it. (A spokesperson for the Belgian federal police said that it respects “a legal framework as to the use of intrusive methods in private life.”) A senior European law-enforcement official whose agency uses Pegasus said that it gave an inside look at criminal organizations: “When do they want to store the gas, to go to the place, to put the explosive?” He said that his agency uses Pegasus only as a last resort, with court approval, but conceded, “It’s like a weapon. . . . It can always occur that an individual uses it in the wrong way.”

The United States has been both a consumer and a victim of this technology. Although the National Security Agency and the C.I.A. have their own surveillance technology, other government offices, including in the military and in the Department of Justice, have bought spyware from private companies, according to people involved in those transactions. The Times has reported that the F.B.I. purchased and tested a Pegasus system in 2019, but the agency denied deploying the technology.

Establishing strict rules about who can use commercial spyware is complicated by the fact that such technology is offered as a tool of diplomacy. The results can be chaotic. The Times has reported that the C.I.A. paid for Djibouti to acquire Pegasus, as a way to fight terrorism. According to a previously unreported investigation by WhatsApp, the technology was also used against members of Djibouti’s own government, including its Prime Minister, Abdoulkadar Kamil Mohamed, and its Minister of the Interior, Hassan Omar.

Last year, as the Washington Post reported and Apple disclosed in a legal filing, the iPhones of eleven people working for the U.S. government abroad, many of them at its embassy in Uganda, were hacked using Pegasus. NSO Group said that, “following a media inquiry” about the incident, the company “immediately shut down all the customers potentially relevant to this case, due to the severity of the allegations, and even before we began the investigation.” The Biden Administration is investigating additional targeting of U.S. officials, and has launched a review of the threats posed by foreign commercial hacking tools. Administration officials told me that they now plan to take new, aggressive steps. The most significant is “a ban on U.S. government purchase or use of foreign commercial spyware that poses counterintelligence and security risks for the U.S. government or has been improperly used abroad,” Adrienne Watson, a White House spokesperson, said.

In November, the Commerce Department added NSO Group, along with several other spyware makers, to a list of entities blocked from purchasing technology from American companies without a license.

I was with Hulio in New York the next day. NSO could no longer legally buy Windows operating systems, iPhones, Amazon cloud servers—the kinds of products it uses to run its business and build its spyware. “It’s outrageous,” he told me.“We never sold to any country which is not an ally with the U.S., or an ally of Israel. We’ve never sold to any country the U.S. doesn’t do business with.” Deals with foreign clients require “direct written approval from the government of Israel,” Hulio said.

“I think that it is not well understood by American leaders,” Eva Galperin, the director of cybersecurity at the watchdog group Electronic Frontier Foundation, told me. “They keep expecting that the Israeli government will crack down on NSO for this, whereas, in fact, they’re doing the Israeli government’s bidding.” Last month, the Washington Post reported that Israel had blocked Ukraine from purchasing Pegasus, not wanting to alienate Russia. “Everything that we are doing, we got the permission from the government of Israel,” Hulio told me. “The entire mechanism of regulation in Israel was built by the Americans.”

NSO sees itself as a type of arms dealer, operating in a field without established norms. Hulio said, “There is the Geneva Conventions for the use of a weapon. I truly believe that there should be a convention of countries that should agree between themselves on the proper use of such tools” for cyber warfare. In the absence of international regulation, a battle is taking place between private companies: on one side, firms like NSO; on the other, the major technology platforms through which such firms implement their spyware.

On Thursday, May 2, 2019, Claudiu Dan Gheorghe, a software engineer, was working at Building 10 on Facebook’s campus in Menlo Park, where he managed a team of seven people responsible for WhatsApp’s voice- and video-calling infrastructure. Gheorghe, who was born in Romania, is thirty-five, with a slight frame and dark, close-cropped hair. In a photograph he used as a professional head shot during his nine years at Facebook, he wears a black hoodie and looks a little like Elliot Alderson, the protagonist of the hacking drama “Mr. Robot.” Building 10 is a two-story structure with open-plan workspaces, brightly colored accent walls, and whiteboards. Engineers, most of them in their twenties and thirties, hunch over keyboards. The word “focus” is written on a wall and stamped on magnets scattered around the office. “It often felt like a church,” Gheorghe recalled. WhatsApp, which Facebook bought for nineteen billion dollars in 2014, is the world’s most popular messaging application, with about two billion monthly users.

Facebook had presented the platform, which uses end-to-end encryption, as ideal for sensitive communications; now the company’s security team was more than two years into an effort to reinforce the security of its products. One task entailed looking at “signalling messages” automatically sent by WhatsApp users to the company’s servers, in order to initiate calls. That evening, Gheorghe was alerted to an unusual signalling message. A piece of code that was intended to dictate the ringtone contained, instead, code with strange instructions for the recipient’s phone.

In a system as vast as Facebook’s, anomalies were routine, and usually innocuous. Unfamiliar code can stem from an older version of the software, or it can be a stress test by Facebook’s Red Team, which conducts simulated attacks. But, as engineers in Facebook’s international offices awoke and began to scrutinize the code, they grew concerned. Otto Ebeling, who worked on Facebook’s security team in London, told me that the code seemed “polished, slick, which was alarming.” Early on the morning after the message was discovered, Joaquin Moreno Garijo, another member of the London security team, wrote on the company’s internal messaging system that, owing to how sophisticated the code was, “we believe that attacker may have found a vulnerability.” Programmers who work on security issues often describe their work in terms of vulnerabilities and exploits. Ivan Krstić, an engineer at Apple, compared the concept to a heist scene in the film “Ocean’s Twelve,” in which a character dances through a hall filled with lasers that trigger alarms. “In that scene, the vulnerability is that there exists a path through all the lasers, where it’s possible to get across the room,” Krstić said. “But the exploit is that somebody had to be a precise enough dancer to actually be able to do that dance.”

By late Sunday, a group of engineers working on the problem had become convinced that the code was an active exploit, one that was attacking vulnerabilities in their infrastructure as they watched. They could see that data were being copied from users’ phones. “It was scary,” Gheorghe recalled. “Like the world is sort of shaking under you, because you built this thing, and it’s used by so many people, but it has this massive flaw in it.”

The engineers quickly identified ways to block the offending code, but they debated whether to do so. Blocking access would tip off the attackers, and perhaps allow them to erase their tracks before the engineers could make sure that any solution closed all possible avenues of attack. “That would be like chasing ghosts,” Ebeling said. “Made a decision to not roll out the server-side fix,” Andrey Labunets, a WhatsApp security engineer, wrote, in an internal message, “because we don’t understand the root cause the impact for users and other possible attacker numbers / techniques.”

On Monday, at crisis meetings with WhatsApp’s top executive, Will Cathcart, and Facebook’s head of security, the company told its engineers around the world that they had forty-eight hours to investigate the problem. “What would the scale of the victims be?” Cathcart recalled worrying. “I mean, how many people were hit by this?” The company’s leadership decided not to notify law enforcement immediately, fearing that U.S. officials might tip off the hackers. “There’s a risk of—you might go to someone who’s a customer,” he told me. (Their concerns were valid: weeks later, the Times has reported, the F.B.I. hosted NSO engineers at a facility in New Jersey, where the agency tested the Pegasus software it had purchased.) Cathcart alerted Mark Zuckerberg, who considered the problem “horrific,” Cathcart recalled, and pressed the team to work quickly. For Gheorghe, “it was a terrifying Monday. I woke up at like 6 a.m., and then I worked until I couldn’t stay awake anymore.”

NSO’s headquarters are in a glass-and-steel office building in Herzliya, a suburb outside Tel Aviv. The area is home to a cluster of technology firms from Israel’s thriving startup sector. The beach is a twenty-minute walk away. The world’s most notorious commercial hacking enterprise is remarkably unprotected: at times, a single security guard waved me through.

On the building’s fourteenth floor, programmers wearing hoodies gather in a cafeteria outfitted with an espresso machine and an orange juicer, or sit on a terrace with views of the Mediterranean. A poster reads “life was much easier when apple and blackberry were just fruits.” Stairs descend to the various programming groups, each of which has its own recreational space, with couches and PlayStation 5s. The Pegasus team likes to play Electronic Arts’ football game, fifa.

Employees told me that the company keeps its technology covert through an information-security department with several dozen experts. “There is a very large department in the company which is in charge of whitewashing, I would say, all connection, all network connection between the client back to NSO,” a former employee said. “They are purchasing servers, V.P.N. servers around the world. They have, like, this whole infrastructure set up so none of the communication can be traced.”

Despite these precautions, WhatsApp engineers managed to trace data from the hack to I.P. addresses tied to properties and Web services used by NSO. “We now knew that one of the biggest threat actors in the world has a live exploit against WhatsApp,” Gheorghe recalled. “I mean, it was exciting, because it’s very rare to catch some of these things. But, at the same time, it was also extremely scary.” A picture of the victims began to emerge. “Likely there are journalists human rights activists and others on the list,” Labunets, the security engineer, wrote on the company’s messaging system. (Eventually, the team identified some fourteen hundred WhatsApp users who had been targeted.)

By midweek, about thirty people were working on the problem, operating in a twenty-four-hour relay, with one group going to sleep as another came online. Facebook extended the team’s deadline, and they began to reverse engineer the malicious code. “To be honest, it’s brilliant. I mean, when you look at it, it feels like magic,” Gheorghe said. “These people are very smart,” he added. “I don’t agree with what they do, but, man, that is a very complicated thing they built.” The exploit triggered two video calls in close succession, one joining the other, with the malicious code hidden in their settings. The process took only a few seconds, and deleted any notifications immediately afterward. The code used a technique known as a “buffer overflow,” in which an area of memory on a device is overloaded with more data than it can accommodate. “It’s like you’re writing on a piece of paper and you go beyond the bounds,” Gheorghe explained. “You start writing on whatever the surface is, right? You start writing on the desk.” The overflow allows the software to overwrite surrounding sections of memory freely. “You can make it do whatever you want.”

I spoke with a vice-president for product development at NSO, whom the firm requested I identify only by his first name, Omer—citing, without apparent irony, privacy concerns. “You find the nooks and crannies enabling you to do something that the product designer didn’t intend,” Omer told me. Once in control, the exploit loaded more software, allowing the attacker to extract data or activate a camera or a microphone. The entire process was “zero click,” requiring no action from the phone’s owner.

The software was designed by NSO’s Core Research Group, made up of several dozen software developers. “You’re looking for a silver bullet, a simple exploit that can cover as much mobile devices around the world,” Omer told me. Gheorghe said, “A lot of people, you know, would think about the hackers as being, like, just one person in a dark room, like, typing on a keyboard, right? That’s not the reality—these people are just, like, another tech company.” It is common for tech companies to hire people with backgrounds in hacking, and to offer bounties to outside programmers who identify vulnerabilities in their systems. Facebook’s headquarters have the vanity address 1 Hacker Way. At both NSO and WhatsApp, the engineers closest to the coding are often described by colleagues as quirky introverts, resembling the hacker archetypes of fiction. “They are special people. Not all of them can communicate clearly with other human beings,” Omer said, of the programmers who work on Pegasus. “Some of them don’t sleep for two days. They get crazy when they don’t sleep.”

Late in the week, Facebook’s security team devised an act of subterfuge: they would simulate an infected device, to get NSO’s servers to send them a copy of the code. “But their software was smart enough to basically not be tricked by this,” Gheorghe said. “We never really were able to get our hands on that.”

Omer told me, “It’s a cat-and-mouse game.” Although NSO says that its customers control the use of Pegasus, it does not dispute its direct role in these exchanges. “Every day, things are being patched,” Hulio said. “This is the routine work here.”

At times, WhatsApp users received repeated missed calls, but the malware wasn’t successfully installed. Once the engineers learned about these incidents, they were able to study what it looked like when Pegasus failed. Toward the end of the week, Gheorghe told me, “we said, O.K., we don’t have a full understanding at this point, but I think we captured enough.” On Friday morning, Facebook notified the Department of Justice, which is developing a case against NSO. Then the company updated its servers to block the malicious code. “Ready to roll,” Gheorghe wrote on the internal messaging service that afternoon. The fix was constructed to look like routine server maintenance, so that NSO might continue to attempt attacks, providing Facebook with more data.

The next day, WhatsApp engineers said, NSO began to send what looked like decoy data packets, which they speculated were a way to determine whether NSO’s activities were being watched. “In one of the malicious packets, they actually sent a YouTube link,” Gheorghe told me. “We were all laughing like crazy when we saw what it was.” The link was to the music video for the Rick Astley song “Never Gonna Give You Up,” from 1987. Ambushing people with a link to the song is a popular trolling tactic known as Rickrolling. Otto Ebeling recalled, “Rickrolling is, I don’t know, something my colleague might do to me, not some sort of semi-state-sponsored people.” Cathcart told me, “There was a message in it. They were saying, We know what you did, we see you.” (Hulio and other NSO employees said they could not recall Rickrolling WhatsApp.)

In the months that followed, WhatsApp began notifying users who had been targeted. The list included numerous government officials, including at least one French ambassador and the Djiboutian Prime Minister. “There wasn’t, you know, overlap between this list and, like, legitimate law-enforcement outreach,” Cathcart said. “You could see, wow, there’s a lot of countries all around the world. This isn’t just one agency or organization in one country targeting people.” WhatsApp also began working with the Citizen Lab, which warned victims of the risk that they might be hacked again, and helped them secure their devices. John Scott-Railton said, “It really was interesting how many people were upset and saddened, but in a deep way not surprised, almost relieved, as if they were getting a diagnosis for a mystery ailment they had suffered for many years.”

Five people in the initial group identified by WhatsApp were Catalans, including elected lawmakers and an activist. Campo, the Catalan security researcher, realized that the cases “were probably just the tip of the iceberg.” He added, “That’s when I found myself in the intersection of technology—a product that I contributed to building—and my home country.”

WhatsApp continued sharing information with the Department of Justice, and, that fall, the company sued NSO in federal court. NSO Group “breached our systems, damaged us,” Cathcart told me. “I mean, do you just do nothing about that? No. There have to be consequences.”

Hulio said, “I just remember that one day the lawsuit happened, and they shut down the Facebook account of our employees, which was a very bully move for them to do.” He added, referring to scandals about Facebook’s role in society, “I think it’s a big hypocrisy.” NSO has pushed for the suit to be dismissed, arguing that the company’s work on behalf of governments should grant it the same immunity from lawsuits that those governments have. So far, the U.S. courts have rejected this argument.

WhatsApp’s aggressive posture was unusual among big technology companies, which are often reluctant to call attention to instances in which their systems have been compromised. The lawsuit signalled a shift. The tech companies were now openly aligned against the spyware venders. Gheorghe described it as “the moment the whole thing just exploded.”

Microsoft, Google, Cisco, and others filed a legal brief in support of WhatsApp’s suit. Goodwin, the Microsoft executive, helped to assemble the coalition of companies. “We could not let NSO Group prevail with an argument that, simply because a government is using your products and services, you get sovereign immunity,” she told me. “The ripple effect of that would have been so dangerous.” Hulio argues that when governments use Pegasus they’re less likely to lean on platform holders for wider “back door” access to users’ data. He expressed exasperation with the lawsuit. “Instead of them, like, actually saying, ‘O.K., thank you,’ ” he told me, “they are going to sue us. Fine, so let’s meet in court.”

Microsoft, too, has a security team that engages in combat with hackers. Although Pegasus is not designed to target users through Microsoft platforms, at least four people in Catalonia running Microsoft Windows on their computers have been attacked by spyware made by Candiru, a startup founded by former NSO employees. (A spokesperson for Candiru said that it requires its products to be used for the “sole purpose of preventing crime and terror.”) In February, 2021, the Citizen Lab identified evidence of an active infection—a rarity for spyware of this calibre—on a laptop belonging to Joan Matamala, an activist closely connected to separatist politicians. Campo called Matamala and instructed him to wrap the laptop in aluminum foil, a makeshift way of blocking the malware from communicating with servers. The Citizen Lab was able to extract a copy of the spyware, which Microsoft dubbed DevilsTongue. Several months later, Microsoft released updates blocking DevilsTongue and preventing future attacks. By then, the list of activists and journalists targeted “made the hairs on the back of our neck stand on end,” Goodwin said. Matamala has been targeted more than sixteen times. “I still have the aluminum paper stored here, in case we ever have a suspicion of having another infection,” he told me.

Last November, after iPhone users were allegedly targeted by NSO, Apple filed its own lawsuit. NSO has filed a motion to dismiss. “Apple is a company that does not believe in theatrical lawsuits,” Ivan Krstić, the engineer, told me. “We have this entire time been waiting for a smoking gun that would let us go file a suit that is winnable.”

Apple created a threat-intelligence team nearly four years ago. Two Apple employees involved in the work told me that it was a response to the spread of spyware, exemplified by NSO Group. “NSO is a big pain point,” one of the employees told me. “Even before the stuff that hit the news, we had disrupted NSO a number of times.” In 2020, with the launch of its iOS 14 software, Apple had introduced a system called BlastDoor, which moved the processing of iMessages—including any potentially malicious code—into a chamber connected to the rest of the operating system by only a single, narrow pipeline of data. But Omer, the NSO V.P., told me that “newer features usually have some holes in their armor,” making them “more easy to target.” Krstić conceded that there was “a sort of an eye of a needle of an opening still left.”

In March, 2021, Apple’s security team received a tip that a hacker had successfully threaded that needle. Even cyber warfare has double agents. A person familiar with Apple’s threat-intelligence capabilities said that the company’s team sometimes receives tips from informants connected to spyware enterprises: “We’ve spent a long time and a lot of effort in trying to get to a place where we can actually learn something about what’s going on deeply behind the scenes at some of these companies.” (An Apple spokesperson said that Apple does not “run sources” within spyware companies.) The spyware venders, too, rely on intelligence gathering, such as securing pre-release versions of software, which they use to design their next attacks. “We follow the publications, we follow the beta versions of whatever apps we’re targeting,” Omer told me.

That month, researchers from the Citizen Lab contacted Apple: the phone of a Saudi women’s-rights activist, Loujain al-Hathloul, had been hacked through iMessage. Later, the Citizen Lab was able to send Apple a copy of an exploit, which the researcher Bill Marczak discovered after months of scrutinizing Hathloul’s phone, buried in an image file. The person familiar with Apple’s threat-intelligence capabilities said that receiving the file, through an encrypted digital channel, was “sort of like getting a thing handed to you in a biohazard bag, which says, ‘Do not open except in a Biosafety Level 4 lab.’ ”

Apple’s investigation took a week and involved several dozen engineers based in the United States and Europe. The company concluded that NSO had injected malicious code into files in Adobe’s PDF format. It then tricked a system in iMessage into accepting and processing the PDFs outside BlastDoor. “It’s borderline science fiction,” the person familiar with Apple’s threat-intelligence capabilities said. “When you read the analysis, it’s hard to believe.” Google’s security-research team, Project Zero, also studied a copy of the exploit, and later wrote in a blog post, “We assess this to be one of the most technically sophisticated exploits we’ve ever seen, further demonstrating that the capabilities NSO provides rival those previously thought to be accessible to only a handful of nation states.” In the NSO offices, programmers in the Core Research Group printed a copy of the post and hung it on the wall.

Apple shipped updates for its platforms that rendered the exploit useless. Krstić told me that this was “a massive point of pride” for the team. But Omer told me, “We saw it coming. We just counted the days until it happened.” He and others at the company said the next exploit is an inevitability. “There might be some gaps. It could take two weeks to come up with a mitigation on our side, some work-around.”

During interviews in NSO’s offices last month, employees exchanged nervous glances with hovering public-relations staffers as they answered questions about morale in the midst of the scandals, lawsuits, and blacklisting. “To be honest, not every time the mood is actually good,” Omer said. Others claimed loyalty to the company and belief in the power of its tools to catch criminals. “The company has a very strong narrative that it tries to sell internally to the employees,” the former employee told me. “You’re either with them or against them.”

Israel has become the world’s most significant source of private surveillance technology in part because of the quality of talent and expertise produced by its military. “Because of the compulsory service, we can recruit the best of the best,” the former senior intelligence official told me. “The American dream is going from M.I.T. to Google. The Israeli dream is to go to 8200,” the Israeli military-intelligence unit from which spyware venders often recruit. (Hulio, who describes himself as a mediocre student whose upbringing was “nothing fancy,” often emphasizes that he did not serve in Unit 8200.) NSO has historically been regarded as an appealing job prospect for young veterans. But the former NSO employee, who quit after becoming concerned that Pegasus had facilitated Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, told me that others had become disillusioned, too. “Many of my colleagues decided to leave the company at that stage,” the former employee said. “This was one of the major events that I think caused many of the employees to, like, wake up and understand what’s going on.” In the past few years, the departures have been “like a snowball.” Hulio, in response to questions about the company’s problems, said, “What worries me is the vibes of the employees.”

In 2019, NSO was saddled with hundreds of millions of dollars in debt as part of a leveraged-buyout deal in which a London-based private-equity firm, Novalpina, acquired a seventy-per-cent stake. Recently, Moody’s, the financial-services firm, downgraded NSO’s credit rating to “poor,” and Bloomberg described it as a distressed asset, shunned by Wall Street traders. Two top NSO executives have left, and relations between the company and its backers have deteriorated. Infighting among Novalpina’s partners led to the transfer of control of its assets, including NSO, to a consulting firm, Berkeley Research Group, which pledged to increase oversight. But a BRG executive recently claimed that coöperation with Hulio had become “virtually non-existent.” Agence France-Presse has reported that tensions emerged because NSO’s creditors have pressed for continued sales to countries with dubious human-rights records, while BRG has sought to pause them. “We indeed have some disputes with them,” Hulio said, of BRG. “It’s about how to run the business.”

NSO’s troubles have complicated its close alliance with the Israeli state. The former senior intelligence official recalled that, in the past, when his unit turned down European countries seeking intelligence collaboration, “Mossad said, Here’s the next best thing, NSO Group.” Several people familiar with those deals said that Israeli authorities provided little ethical guidance or restraint. The former official added, “Israeli export control was not dealing with ethics. It was dealing with two things. One, Israeli national interest. Two, reputation.” The former NSO employee said that the state “was well aware of the misuse, and even using it as part of its own diplomatic relationships.” (Israel’s Ministry of Defense said in a statement that “each licensing assessment is made in light of various considerations including the security clearance of the product and assessment of the country toward which the product will be marketed. Human rights, policy, and security issues are all taken into consideration.”) After the blacklisting of NSO, Hulio sought to enlist Israeli officials, including Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Defense Minister Benny Gantz. “I sent a letter,” he told me. “I said that as a regulated company, you know, everything that we have ever asked was with the permission, and with the authority, of the government of Israel.” But a senior Biden Administration official said that the Israelis raised only “pretty mild complaints” about the blacklisting. “They didn’t like it, but we didn’t have a standoff.”

In Israel’s legislature, Arab politicians are leading a modest movement to examine the state’s relationship with NSO. The Arab party leader Sami Abou Shahadeh told me, “We tried to discuss this in the Knesset twice . . . to tell the Israeli politicians, You are selling death to very weak societies that are in conflict, and you’ve been doing this for too long.” He added, “It never worked, because, first and morally, they don’t see any problem with that.” Last fall, an investigation by the watchdog group Front Line Defenders identified Pegasus infections on the phones of six Palestinian activists—including one whose Jerusalem residency status had been revoked. Abou Shahadeh argued that the history of Israel’s spyware technology is tied to the surveillance of Palestinian communities in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza. “They have a huge laboratory,” he told me. “When they were using all the same tools for a long time to spy on Palestinian citizens, nobody cared.” Asked about the targeting of Palestinians, Hulio said, “If Israel is using our tools to fight crime and terror, I would be very proud of it.”

“Iknow there have been misuses,” Hulio said. “It’s hard for me to live with that. And I obviously feel sorry for that. Really, I’m not just saying that. I never said it, but I’m saying it now.” Hulio said that the company has turned down ninety customers and hundreds of millions of dollars of business out of concern about the potential for abuse. But such claims are difficult to verify. “NSO wanted Western Europe mainly so they can tell guys like you, Here’s a European example,” the former Israeli intelligence official, who now works in the spyware sector, said. “But most of their business is subsidized by the Saudi Arabias of the world.” The former employee, who had knowledge of NSO’s sales efforts, said, “For a European country, they would charge ten million dollars. And for a country in the Middle East they could charge, like, two hundred and fifty million for the same product.” This seemed to create perverse incentives: “When they understood that they had misuse in those countries that they sold to for enormous amounts of money, then the decision to shut down the service for that specific country became much, much harder.”

Asked about the extreme abuses ascribed to his technology, Hulio invoked an argument that is at the heart of his company’s defense against WhatsApp and Apple. “We have no access to the data on the system,” he told me. “We don’t take part in the operation, we don’t see what the customers are doing. We have no way of monitoring it.” When a client buys Pegasus, company officials said, an NSO team travels to install two racks, one devoted to storage and another for operating the software. The system then runs with only limited connection to NSO in Israel.

But NSO engineers concede that there is some real-time monitoring of systems to prevent unauthorized tampering with or theft of their technology. And the former employee said, of Hulio’s assurances that NSO is technically prevented from overseeing the system, “That’s a lie.” The former employee recalled support and maintenance efforts that involved remote access by NSO, with the customer’s permission and live oversight. “There is remote access,” the former employee added. “They can see everything that goes on. They have access to the database, they have access to all of the data.” The senior European law-enforcement official told me, “They can have remote access to the system when we authorize them to access the system.”

NSO executives argue that, in an unregulated field, they are attempting to construct guardrails. They have touted their appointment of a compliance committee, and told me that they now maintain a list of countries ranked by risk of misuse, based on human-rights indicators from Freedom House and other groups. (They declined to share the list.) NSO also says that customers’ Pegasus systems maintain a file that records which numbers were targeted; customers are contractually obligated to surrender the file if NSO starts an investigation. “We have never had a customer say no,” Hulio told me. The company says that it can terminate systems remotely, and has done so seven times in the past few years.

The competition, Hulio argued, is far more frightening. “Companies found themselves in Singapore, in Cyprus, in other places that don’t have real regulation,” he told me. “And they can sell to whoever they want.” The spyware industry is also full of rogue hackers willing to crack devices for anyone who will pay. “They will take your computers, they will take your phone, your Gmail,” Hulio said. “It’s obviously illegal. But it’s very common now. It’s not that expensive.” Some of the technology that NSO competes with, he says, comes from state actors, including China and Russia. “I can tell you that today in China, today in Africa, you see the Chinese government giving capabilities almost similar to NSO.” According to a report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, China supplies surveillance tools to sixty-three countries, often through private firms enmeshed with the Chinese state. “NSO will not exist tomorrow, let’s say,” Hulio told me. “There’s not going to be a vacuum. What do you think will happen?”

NSO is also competing with Israeli firms. Large-scale hacking campaigns, like the one in Catalonia, often use tools from a number of companies, several founded by NSO alumni. Candiru was started in 2014, by the former NSO employees Eran Shorer and Yaakov Weizman. It was allegedly linked to recent attacks on Web sites in the U.K. and the Middle East (Candiru denies the connection), and its software has been identified on the devices of Turkish and Palestinian citizens. Candiru has no Web site. The firm shares its name with a parasitic fish, native to the Amazon River basin, that drains the blood of larger fish.

QuaDream was founded two years later, by a group including two other former NSO employees, Guy Geva and Nimrod Reznik. Like NSO, it focusses on smartphones. Earlier this year, Reuters reported that QuaDream had exploited the same vulnerability that NSO used to gain access to Apple’s iMessage. QuaDream, whose offices are behind an unmarked door in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan, appears to share with many of its competitors a reliance on regulation havens: its flagship malware, Reign, is reportedly owned by a Cyprus-based entity, InReach. According to Haaretz, the firm is among those now employed by Saudi Arabia. (QuaDream could not be reached for comment.)

Other Israeli firms pitch themselves as less reputationally fraught. Paragon, which was founded in 2018 by former Israeli intelligence officials and includes former Prime Minister Ehud Barak on its board, markets its technology to offices within the U.S. government. Paragon’s core technology focusses not on seizing complete control of phones but on hacking encrypted messaging systems like Telegram and Signal. An executive told me that it has committed to sell only to a narrow list of countries with relatively uncontroversial human-rights records: “Our strategy is to have values, which is interesting to the American market.”

In Catalonia, Gonzalo Boye, an attorney representing nineteen people targeted by Pegasus, is preparing criminal complaints to courts in Spain and other European countries, accusing NSO, as well as Hulio and his co-founders, of breaking national and E.U. laws. Boye has represented Catalan politicians in exile, including the former President Carles Puigdemont. Between March and October of 2020, analysis by the Citizen Lab found, Boye was targeted eighteen times with text messages masquerading as updates from Twitter and news sites. At least one attempt resulted in a successful Pegasus infection. Boye says that he now spends as much time as possible outside Spain. In a recent interview, he wondered, “How can I defend someone, if the other side knows exactly everything I’ve said to my client?” Hulio declined to identify specific customers but suggested that Spain’s use of the technology was legitimate. “Spain definitely has a rule of law,” he told me. “And if everything was legal, with the approval of the Supreme Court, or with the approval of all the lawful mechanisms, then it can’t be misused.” Pere Aragonès, the current President of Catalonia, told me, “We are not criminals.” He is one of three people who have served in that role whose phones have been infected with Pegasus. “What we want from the Spanish authorities is transparency.”

Last month, the European Parliament formed a committee to look into the use of Pegasus in Europe. Last week, Reuters reported that senior officials at the European Commission had been targeted by NSO spyware. The investigative committee, whose members include Puigdemont, will convene for its first session on April 19th. Puigdemont called NSO’s activities “a threat not only for the credibility of Spanish democracy, but for the credibility of European democracy itself.”

NSO Group also faces legal consequences in the U.K.: three activists recently notified the company, as well as the governments of Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E., that they plan to sue over alleged abuses of Pegasus. (The company responded that there was “no basis” for their claims.)

NSO continues to defend itself in the WhatsApp suit. This month, it filed an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. “If we need to go and fight, we will,” Shmuel Sunray, NSO’s general counsel, told me. Lawyers for WhatsApp said that, in their fight with NSO, they have encountered underhanded tactics, including an apparent campaign of private espionage.

On December 20, 2019, Joe Mornin, an associate at Cooley L.L.P., a Palo Alto law firm that was representing WhatsApp in its suit against NSO, received an e-mail from a woman who identified herself as Linnea Nilsson, a producer at a Stockholm-based company developing a documentary series on cybersecurity. Nilsson was cagey about her identity but so eager to meet Mornin that she bought him a first-class plane ticket from San Francisco to New York. The ticket was paid for in cash, through World Express Travel, an agency that specialized in trips to Israel. Mornin never used the ticket. A Web site for the documentary company, populated with photos from elsewhere on the Internet, soon disappeared. So did a LinkedIn profile for Nilsson.

Several months later, a woman claiming to be Anastasia Chistyakova, a Moscow-based trustee for a wealthy individual, contacted Travis LeBlanc, a Cooley partner working on the WhatsApp case, seeking legal advice. The woman sent voice-mail, e-mail, Facebook, and LinkedIn messages. Mornin identified her voice as belonging to Nilsson, and the law firm later concluded that her e-mail had come from the same block of I.P. addresses as those sent by Nilsson. The lawyers reported the incidents to the Department of Justice.

The tactics were similar to those used by the private intelligence company Black Cube, which is run largely by former officers of Mossad and other Israeli intelligence agencies, and is known for using operatives with false identities. The firm worked on behalf of the producer Harvey Weinstein to track women who had accused him of sexual abuse, and last month three of its officials received suspended prison sentences for hacking and intimidating Romania’s chief anti-corruption prosecutor.

Black Cube has been linked to at least one other case involving NSO Group. In February, 2019, the A.P. reported that Black Cube agents had targeted three attorneys involved in another suit against NSO Group, as well as a London-based journalist covering the case. The lawyers—Mazen Masri, Alaa Mahajna, and Christiana Markou—who represented hacked journalists and activists, had sued NSO and an affiliated entity in Israel and Cyprus. In late 2018, all three received messages from people who claimed to be associated with a rich firm or individual, repeatedly suggesting meetings in London. NSO Group has denied hiring Black Cube to target opponents. However, Hulio acknowledged the connection to me, saying, “For the lawsuit in Cyprus, there was one involvement of Black Cube,” because the lawsuit “came from nowhere, and I want to understand.” He said that he had not hired Black Cube for other lawsuits. Black Cube said that it would not comment on the cases, though a source familiar with the company denied that it had targeted Cooley lawyers.

“People can survive and can adapt to almost any situation,” Hulio once told me. NSO Group must now adapt to a situation in which its flagship product has become a symbol of oppression. “I don’t know if we’ll win, but we will fight,” he said. One solution was to expand the product line. The company demonstrated for me an artificial-intelligence tool, called Maestro, that scrutinizes surveillance data, builds models of individuals’ relationships and schedules, and alerts law enforcement to variations of routine that might be harbingers of crime. “I’m sure this will be the next big thing coming out of NSO,” Leoz Michaelson, one of its designers, told me. “Turning every life pattern into a mathematical vector.”

The product is already used by a handful of countries, and Hulio said that it had contributed to an arrest, after a suspect in a terrorism investigation subtly altered his routine. The company seemed to have given little consideration to the idea that this tool, too, might spur controversy. When I asked what would happen if law enforcement arrested someone based on, say, an innocent trip to the store in the middle of the night, Michaelson said, “There could be false positives.” But, he added, “this guy that is going to buy milk in the middle of the night is in the system for a reason.”

Yet the risk to bystanders is not an abstraction. Last week, Elies Campo decided to check the phones of his parents, scientists who are not involved in political activities, for spyware. He found that both had been infected with Pegasus when he visited them during the Christmas holiday in 2019. Campo told me, “The idea that anyone could be at risk from Pegasus wasn’t just a concept anymore—it was my parents sitting across the table from me.” On his mother’s phone, which had been hacked eight times, the researchers found a new kind of zero-click exploit, which attacked iMessage and iOS’s Web-browsing engine. There is no evidence that iPhones are still vulnerable to the exploit, which the Citizen Lab has given the working name Homage. When the evidence was found, Scott-Railton told Campo, “You’re not going to believe this, but your mother is patient zero for a previously undiscovered exploit.”

During a recent visit to NSO’s offices, windows and whiteboards across the space were dense with flowcharts and graphics, in Hebrew and English text, chronicling ideas for products and exploits. On one whiteboard, scrawled in large red Hebrew characters and firmly underlined, was a single word: “War!” ♦

Georgia Gee conducted additional research for this piece.

An earlier version of this story misstated the time of a Pegasus infection on a device connected to the network at 10 Downing Street.

Ronan Farrow is an investigative reporter and a contributing writer to The New Yorker. He is also currently producing documentaries for HBO. His stories for The New Yorker exposed the first sexual-assault allegations against the movie producer Harvey Weinstein and the first misconduct allegations against CBS executives, including then C.E.O. Leslie Moonves. He was also responsible for the first detailed accounts of payments made by the National Enquirer’s parent company in order to suppress stories about Donald Trump during the 2016 Presidential campaign. For his reporting on Weinstein, Farrow won the Pulitzer Prize for public service, the National Magazine Award, and the George Polk Award, among other honors. He previously worked as an anchor and investigative reporter at MSNBC and NBC News, with his print commentary and reporting appearing in publications including the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, and the Washington Post. Farrow is the author of “War on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence” and “Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators.” He is a graduate of Yale Law School and a member of the New York Bar. He recently completed a Ph.D. in political science at Oxford University, where he studied as a Rhodes Scholar. Prior to his career in journalism, he served as a State Department official in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He lives in New York. @RonanFarrow

The New Yorker. Spring Sale. Subscribe now and get a free tote. Cancel anytime.

Spread the word