“I spent 33 years and 4 months in active service as a member of our country's most agile military force—the Marine Corps. I served in all commissioned ranks from a second lieutenant to Major-General. And during that period I spent most of my time being a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.” Smedley D. Butler, major general, U.S. Marine Corps (ret.), 1935

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the United States began building a powerful empire beyond the contiguous states on the North American continent. The US military—often at the behest of American businesses and financial institutions—was at the forefront of interventions in numerous countries from Cuba and Haiti to China and the Philippines. In some cases, the nations were annexed, the usually nonwhite populations were subjugated, and puppet governments that protected American interests were installed through force or other persuasion.

Most of these violent campaigns are now forgotten. For most Americans, this bloody history of American conquest is presented, if at all, as a series of heroic adventures to bring seemingly less advanced peoples our ideals and to prepare them to govern themselves.

The US Marines played a prominent role in making safe for democracy the far-flung targets of American imperialism. And Marine officer Smedley Butler (1881-1940), known as “the Fighting Quaker,” served with distinction in virtually all of these actions to expand American empire.

Butler was the most highly decorated Marine before the Second World War and attained the rank of major general by the time of his retirement in 1931. In the last years of his life, however, he became an unlikely voice against war, fascism, capitalism, and imperialism. Although Butler was a widely revered American hero and darling of the press during his military career, today he is almost unknown, as are the actions he served in and later disavowed, including participating in brutal invasions, improvising terror campaigns, installing puppet leaders, creating militarized police forces to protect American profiteers, and erasing history by destroying archives and silencing anti-American opponents.

Smedley Butler in China, 1900 (Marine Corps History Department)

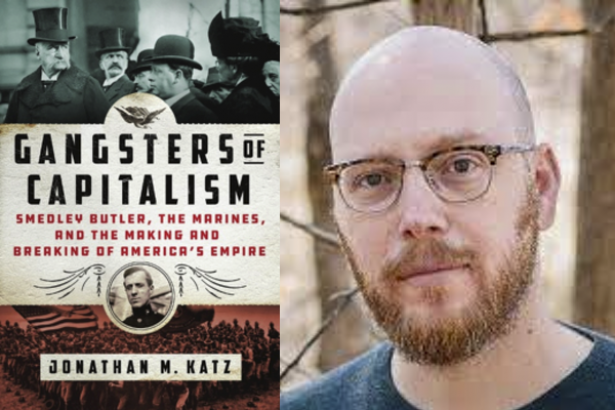

Award-winning author Jonathan M. Katz follows in the footsteps of Smedley Butler as he recounts the early history of American imperialism in his revelatory and groundbreaking new book Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire (St. Martin’s Press). Mr. Katz chronicles Butler’s evolution from his Quaker youth to his military service to his surprising repudiation of war and imperialism in his later years.

Mr. Katz also brings the legacy of past US interventions to the present with his firsthand reports back from his travels to the sites of Butler’s service, the targets of conquest and colonization. This vivid history is based on Mr. Katz’s meticulous research into sources such as Butler’s personal letters and diaries and documents from fellow Marines and political and business leaders, as well as materials from those who fought the Americans and lived under American rule.

Mr. Katz is a widely acclaimed foreign correspondent and author. His first book, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster, was a PEN Literary Award finalist and won the Overseas Press Club of America’s Cornelius Ryan Award for the year’s best book on international affairs. He is also a recipient of the James Foley/Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism. Further, he regularly contributes to the New York Times and other publications as well as offering broadcast commentary on radio and television. He has been a National Fellow at New America and a director of the Media & Journalism Initiative at Duke University’s John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute.

In addition, as the Associated Press correspondent in Haiti in 2010, Mr. Katz survived the deadliest earthquake ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, and he provided the first international alert of that disaster. He later uncovered evidence that United Nations peacekeepers had caused and were covering up a devastating post-quake cholera epidemic. His initial stories prompted him to conduct six more years of investigation along with epidemiologists and legal advocates for the victims.

Mr. Katz generously discussed his work and his new book by telephone from his office in Virginia.

Robin Lindley: Congratulations Mr. Katz on your wide ranging and groundbreaking book Gangsters of Capitalism on the history of American empire. Before getting to the book, I’d like to ask about your background. You really took a deep dive into the research on these overlooked or forgotten American military engagements, wars, occupations, and massacres during the early 20th century. Your research is meticulous. You are an award-winning journalist, but did you also have a background in history?

Jonathan Katz: Thank you. I have a bachelor's degree in American studies and history, and I studied history at the undergraduate level. My wife, Claire Payton, is a professional historian with a PhD in history, so I hesitate to say that I'm trained in history after seeing what it looks like to be trained at the doctoral level.

But I studied history and was inculcated in basic historical methods as an undergrad. I had to re-educate myself with this book. I had never worked in an archive before I started this project, for instance. I had to learn all of that – it was really my wife who gave me my formative instruction on how to navigate the first archive that I went to, the National Archives. Then I went on from there.

And I had some other tools in my background because there’s quite a lot of overlap between the methods of doing journalistic research and historical research. Certainly, in the parts of the book when I’m doing oral history and interviewing people, I drew much more on my experience as a journalist.

I should also acknowledge a great professor from my freshman year at Northwestern. I took an eye-opening course on U.S. diplomatic history with Ken Bain, who is a historian, though these days I believe he mostly teaches other professors how to teach.

Robin Lindley: Your writing about history is lively and accessible. I’m older than you, but I didn’t get much of the American imperial history you share when I was in high school or college. It seems that American foreign policy was framed then in terms of civilizing other nations and bringing the gifts of our idealism to less fortunate people. And I now thought that I knew a lot about the history of American imperialism, but your book revealed much more for me.

Jonathan Katz: I also didn’t learn the history that I cover and recount in this book in my own education growing up. It was a huge blind spot for me as well, despite the fact that I did study some things that you could certainly describe as American imperialism in school. I took Prof. Bain’s course in the mid-nineties on the history of foreign and diplomatic relations from 1945 to the present, but in that one I learned about American imperialism mostly during the Cold War. Even then I knew very little about American imperialism that could really bridge my gap between the end of Reconstruction to World War II. That was just a blind spot in my learning.

Robin Lindley: I realize that you had your own firsthand, personal experience with American imperialism from your years in Haiti. Your powerful earlier book, The Big Truck That Went By, is a brilliant account of your experience there. Did your interest in the history of imperialism grow from your experience in Haiti?

Jonathan Katz: I first encountered that history in my own life when I was based in the Caribbean as an Associated Press correspondent—first for two years in the Dominican Republic, and then for three and a half years in Haiti. I had no idea that the United States had occupied both of those countries for as long as they had. It was a very, very visceral lesson in the endurance and profound effects of American imperial control on those countries and on the people in them. And I experienced that in real time when I was reporting there.

That’s how I came to do this book. I put together the things that I had in my head with history such as the CIA coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala [in 1954] and other things that happened earlier that made sense as an arc. I picked up bits and pieces and then had to assemble them together.

Robin Lindley: Then you focus on the history through the lens of the “Fighting Quaker,” the once revered US Marine officer Smedley Butler, who eventually attained the rank of major general and was the most decorated Marine before World War II. How did you decide to follow in Butler’s footsteps and then become a character yourself by traveling to each country and bringing up to date in the different areas where he served?

Jonathan Katz: I was trying to solve a couple of different problems from a writing standpoint. When I first embarked on the project, I didn’t know if there was going to be enough material directly from Butler’s journals or letters. I was also afraid that the account was going to feel remote to a modern-day audience. And the last thing was that I’m not a professional historian. I'm a journalist, and my core competencies that mark the good parts of my work today are being out in a country, smelling the air, talking to the people, and observing things in real time. I wanted to bring that sensibility to the book.

As it turned out, I actually started digging into the archives, and I learned—much to my shock and glee—that there was a ton of material. Butler had written incredible letters in incredible detail. And there were things written by other Marines, and then by the people that the Marines were fighting against or serving among.

So, the Butler era parts of the book were much richer and much more accessible than I thought they were going to be. That created a new and unexpected writing problem, which was that I then had to make certain that the modern material I was writing would be as interesting and as engaging and as revelatory as the historical stuff. I hope I pulled it off.

Initially, I was trying to solve the problem of keeping a mass audience engaged as if they were there, and it turned out that I had an embarrassment of riches with all of this amazing historical material. I was doing journalism and oral history in the modern day to follow up on the history. That created a writing issue of trying to figure out the structures of all of these themes which was a negotiation that lasted five to seven years. And it wasn't smoke and mirrors to make things seem more relevant. I wanted to show that this era is relevant and the things that happened in Butler’s Day continue. They didn’t begin with him and didn't end at the end of his career or with the Second World War.

Robin Lindley: It's an innovative and engrossing book that has such resonance now. What are a few things you might say to introduce readers to Smedley Butler? He was a distinguished Marine officer who surprisingly dedicated the last years of his life challenging militarism and more. I don't think most people now remember him.

Jonathan Katz: Butler was a Marine who joined the Marine Corps in 1898 during the war against Spain. He was 16 years old, and he lied about his age to join the Corps. His first duty posting was the freshly seized Cuban port of Guantanamo Bay, which the Americans had just taken and have not relinquished since. And from there, he went with very few exceptions to every invasion, intervention, occupation, and war that the United States fought from 1898 on. He retired in 1931as a major general. He was twice the recipient of the Medal of Honor and a number of other awards.

But the thing that really makes him stand out in American history is that he spent the last ten years of his life in the 1930s speaking out against American imperialism and crusading against war in general as well as fascism. The book begins and ends with this episode in his life in 1933 and 1934 when he was approached by a bond salesman who claimed to be representing a group of powerful capitalists, industrialists, and bankers with a plan to essentially overthrow Franklin Roosevelt and replace him with a fascist dictator.

Butler testified to that effect before a congressional committee. Obviously, that plot never came to fruition, but the bond salesman alleged that many people were involved. Today, there are many around the world who have heard of Butler, but the groups that most retain his memory are the Marines who learned about the two Medals of Honor in boot camp; conspiracy theory nuts who learned about “the business plot,” as it has become known; and antiwar activists who like to pass around the pamphlet that he published in 1935, War is a Racket.

Robin Lindley: You vividly recount the many different campaigns that Butler was involved with from Cuba and the Philippines to China, the Caribbean, Central America, and beyond. There were many invasions, wars, coups, and occupations that most people never learn about. For example, I think many people know little or nothing about the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) when the US military crushed a Filipino rebellion for independence and massacred combatants and civilians alike.

Jonathan Katz: It’s very hard to encapsulate all of Butler’s campaigns. That’s why I wrote an entire book about it. But there are multiple ways to speak to the history.

When talking specifically about the Philippines, what happened there was that the United States declared war on the entire Spanish Empire in 1898, which meant not just in Cuba, but in all of Spain's holdings including Puerto Rico, which we took, and then the really big prize of the Philippines, an enormous group of islands 7,000 islands. And the Philippines are across the South China Sea from China, and the big goal of American capitalists was markets that, to this day, people still dream about. If they could just sell goods to one percent of all the people in China, they would get rich. So, people were thinking of that, even then.

The Philippines had been a colony of Spain for three centuries at that point. Like the Cubans, the leaders of the Philippine revolutionary movement against Spain welcomed the Americans at first as partners in their fight for independence only to be betrayed by the Americans. Congress, responding to internal pressure in American politics, had indemnified the US against annexing Cuba. But there was no protection for anywhere else in the Spanish empire, including Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

So, at the end of the war against Spain, the Americans staged a mock battle against the Spanish in which Spain surrendered to the Americans but not to the Filipinos. And the McKinley Administration paid off the Spanish government to the tune of 20 million 1898 dollars. The US then declared itself the colonial master of the Philippines. We annexed it outright and Filipinos clearly did not like that. A war broke out between the Americans and the Filipinos, and that lasted into 1902, with the fighting continuing in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago for another ten years after that.

It was an extraordinarily bloody war. The Americans won and the Philippines became a wholly-owned U.S. colony until World War II. And a year after World War II ended, once we had properly demolished Manila in kicking out the Japanese, the Truman administration finally gave the Philippines its independence. But the country remained, to a large extent, a client state of the United States for decades after that.

The other thing that I would say as an umbrella way of looking at all of these actions is that there were very clear material and political reasons for why American leaders at that moment were so interested in expanding the reach of the United States into all these different territories. A lot of it, as Butler identifies in his writings in the 1930s, comes down to capital. It comes down to specific resources that Americans could gain control over. There were ports and shipping lanes that Americans gain control over. For some people. like Teddy Roosevelt at the beginning, it's very much a political project. He saw an opportunity to use American commercial and military power to create a nation that would rival the major states and empires of Europe. And a lot of other people were along for the ride: bankers, industrialists, shipping merchants, and others.

All of these military episodes provided an opportunity to get in on the commercial ground floor, as Butler said about China, and to control either outright or informally local governments who would defend American access to their markets and their resources against all others. That is what marks essentially all of the episodes that I talk about in the book.

Robin Lindley: And it’s interesting that Butler, in addition to participating in invasions and bloody massacres and occupations, also had a gift for erasing history. You go into that activity in some depth in writing about Haiti around 1915, when the US actually took over the Haitian government.

Jonathan Katz: Yes. The US invaded Haiti in 1915 and declared a formal, official occupation of Haiti. Occupation was a euphemism to suggest we were not colonizing them but were just occupying them for a little while, and that little while ended up being until 1919.

The episode that you're talking about in particular was in 1917 when Butler stormed the Haitian parliament. And remember, Haiti as a country was born in a revolution of enslaved people against slavery and their French colonial masters. They had been a country for over a hundred years at that point in Butler’s career.

Haiti prohibited foreigners from owning land there, and American capitalists don't like that prohibition. Because the US was occupying Haiti, Americans wanted to make money there. They wanted to own land. To own sugar plantations and pineapple fields. Then the State Department crafted a constitution for Haiti. When he ran for vice president in the 1920s on the campaign trail Franklin Roosevelt actually claimed that he personally wrote the constitution, although that's hard to believe considering that this constitution most likely would have come out of the State Department and not the Navy Department where FDR served.

The Haitians didn't want this constitution but we had already decapitated the executive and we selected a puppet president. However, the Parliament was still nominally independent and was preparing to reject ratification of this document. Butler then assembled a column of Marines and Haitian gendarmes, which were the client military that Butler set up in Haiti. They ended up being the model for the future client militaries in places such as the Caribbean and Vietnam and all the way to Iraq and Afghanistan.

So, Butler led the client military, the gendarmes, and his Marines onto the floor of the Haitian Parliament and declared the Parliament shuttered, and the Parliament didn't meet again for another 12 years. In the absence of the Parliament, the Marines and the gendarmes then oversaw an election in which the people were essentially coerced to vote for this constitution.

In the immediate aftermath of the shuttering of Parliament, Butler called all of the newspaper editors in Port au Prince to his office and ordered them not to breathe a word of the details of how Parliament was shut down and how this vote went down. Butler also went to the Parliament building and personally removed from the Parliamentary archive records of the last votes that the Parliament had been undertaking to reject this constitution.

We know about this coup by Butler now because, when Republicans took power in the US in the 1920s, one of their first orders of business was to hold hearings in the Senate to investigate the details of what happened during the occupation of Haiti – which up until then had been overseen by Democrats. They called to testify a witness who would become the first post occupation president of Haiti. He and his colleagues told Senators what happened, which is the only reason that we know. This was a very clear example of the US suppression and destruction of the historical record—in real time.

But the Republicans did nothing to end the occupation of Haiti. It ended up being Franklin Roosevelt who ended the occupation in 1934.

Robin Lindley: As you vividly recount, Butler’s evolution was incredible. He was a devoted Marine who was decorated for serving in brutal campaigns usually against non-white populations in numerous countries. The title of your book, Gangsters of Capitalism, captures a lot about the evolution of this dedicated military officer who turned around in the 1930s to become a voice for anti-imperialism, anti-fascism, and the anti-war movement. And, as you mentioned, he exposed a fascist coup planned by far-right business leaders. That story is especially timely in view of recent anti-democratic movements and the rightwing coup to reverse our free and fair presidential election in 2020. Who was behind the business coup in the 1930s to overthrow the FDR Administration and how was Butler involved?

Jonathan Katz: The bond salesman who approached Butler in 1933 was Gerald C. MacGuire, and he sold bonds for a Wall Street firm headed by a guy named Grayson Mallet-Prevost Murphy who, as I found in my research, was really the linchpin of this plan that evolves over the course of 1933 and 1934.

As it starts out, they want Butler to go to an American Legion meeting and denounce Franklin Roosevelt for taking the dollar off the gold standard. And they try to convince Butler by appealing to him on the basis of what they knew was his immense sympathy for the veterans who were demanding what was known as “the bonus,” the back pay that they had been promised by a succession of presidents going back to Woodrow Wilson for their service in the First World War. To Butler, however, that made no sense. What did the gold standard have to do with the bonus? Nothing.

But the courtship of Butler continued, and by August 1934, MacGuire had been on a junket across fascist Europe. He visited Rome and Berlin, where Mussolini and in Hitler respectively were in power. Also in 1934, MacGuire crucially visited Paris just a couple of weeks after a proto-January 6th moment in which a loose and often infighting confederation of French fascists, far right groups, and a group of breakaway communists stormed the French legislature to prevent essentially a handover of power to a center-left government on the basis of a bunch of conspiracy theories. The idea was that that French Centrists were going to somehow turn France into a new redoubt of Bolshevism.

MacGuire told Butler that [the business plot] would basically do here what they did in France, modeled on a group called the Croix de Feu which was a far right, quasi-fascist, French veterans’ organization. And this business group wanted Butler to lead half a million armed World War I veterans up Pennsylvania Avenue and then surround the White House to intimidate Franklin Roosevelt into either resigning or delegating power to a cabinet secretary who the plotters would name.

MacGuire told Butler, among others, that a group would emerge to back this effort, and Butler identified the group as the American Liberty League which took shape in the weeks after a meeting between Butler and MacGuire in Philadelphia.

Robin Lindley: I don’t recall learning about the Liberty League before reading your book.

Jonathan Katz: The American Liberty League was essentially a political activist group led by some of the wealthiest and most powerful people in America then. It was the brainchild of one of the DuPont brothers of DuPont Chemical, one of the leading weapons manufacturers in the world at the time. There was also Alfred P. Sloan, the head of General Motors, and the heads of McCann Erickson ad agency, Phillips Petroleum, Sun Oil, etc. There were also powerful politicians including the last two Democratic presidential candidates, Al Smith and John W. Davis. And crucially, in terms of our story here, Gerald MacGuire's boss, Grayson Murphy, was the treasurer of the Liberty League. Murphy told Butler that this group would provide the financial muscle, the weapons, the strategy, and so on.

It was with Murphy's allegation to Butler and then Butler's testimony to Congress that the Liberty League would be involved. That is how the business plot involved all of these extremely powerful figures in the Liberty League that sold itself as a society to protect the Constitution, but was actually an anti-New Deal front. These businessmen were capitalists who were afraid that their fellow patrician President Roosevelt would sell them out and basically turn America into a Bolshevik state. That was the way they saw the world, which is still the way that a lot of conservatives today in 2022 see any attempt at social democracy or democratic socialism, including programs like Social Security and the Civilian Conservation Corps and other projects that were part of the New Deal. And that was the Liberty League view.

The Liberty League itself didn’t last for very long as a major force in American politics. The New Deal was so successful that attempts to create coalitions to dismantle it weren’t very successful for the rest of FDR’s presidency. By the time he ran for his third and fourth terms, the Republicans who ran against him had to fashion themselves as liberals to be taken seriously because conservatism was looked down upon. But MacGuire was courting Butler in 1933 at the very beginning of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency when those tendencies had not yet gelled. And Grayson Murphy was a longtime financier with extensive experience in military intelligence. He had been all over the world as part of America’s imperial project. For him or a DuPont or any of the other big, powerful figures of the Liberty League, there was then an opportunity to end the New Deal. They knew that they wouldn’t be able to do it at the ballot box even by 1934, but at least some of them plausibly thought that they could do it using violence, and that’s what we see in the Liberty League.

Robin Lindley: Butler’s testimony put an end to the business coup, it seems. What do you think happened with Butler that caused his evolution, that prompted his antiwar and anti-fascist views in the 1930s? He conceded that, as a Marine, he had been “a high class muscle man” for American business. Did he discover his conscience?

Jonathan Katz: He was a Quaker who came from an antiwar and egalitarian tradition, which was part of the reason, ironically, that he got involved in the Marines in the first place. When he went to war in 1898 against the Spanish, he was fighting an anti-imperialist war. He, like a lot of Americans, had learned about the horrific things that the Spanish were doing in Cuba at that moment. Most notoriously, the Spanish governor general in Cuba invented concentration camps the 1890s.

Butler, in a contradictory, blinkered way, totally disregards the Quaker’s peace testimony, which bans in all wars and all military actions for any pretense whatsoever. But there was a Quaker route for Butler in his mind as he went to help free “little Cuba,” as he put it, from the Spanish. And, maybe to a certain extent and for his own material reasons, he lost sight of his original reasons for joining the Marines. He became obsessed with proving himself as a man and as a Marine.

He accrued status and fame and attracted his wife Ethel, and all of these other things as a Marine officer. But by the 1920s he was starting to turn back a bit [to Quakerism]. I think also that he suffered from what's now known as moral injury. He was someone who grew up with a deep moral code which he was violating over and over again.

On his last Marine mission [in 1927], Butler returned to China for the second time, this time as a general, and he was there basically for first moment of the Chinese Civil War between the Communists and the Nationalists. He spent a couple of years in China and also saw the coming Japanese invasion and occupation. The Japanese were also involved and were there alongside him. He uses power as a general to keep his Marines out of battle and to do everything that he can to prevent the outbreak of what he sees coming: a potential world war in the Pacific, which of course later occurs.

Robin Lindley: And Butler also was defending Standard Oil in China then.

Jonathan Katz: Exactly. He was deployed to Shanghai, and he ended up in Tianjin, the port closest to Beijing, on the Grand Canal near where it hits the ocean. Standard Oil gave the Marines space to station on their compound. Basically, the only real action that his Marines saw in his years in China during that mission was putting out a fire at the Standard Oil compound, which won acclaim.

Standard Oil in particular, and other American business interests, were the main reason the Marines were sent to China because there was spiraling violence in China and Americans wanted defense. And there was a long track record of Marines defending oil interests, most notably in Mexico in 1914, the place where Butler received his first Medal of Honor. He was called into Mexico by the lawyer for Texaco and Standard Oil, William F. Buckley, Sr., who actually asked for the invasion of Mexico in 1914.

Robin Lindley: Did Butler ever express second thoughts about racism and or write with sympathy for the non-white populations that he often engaged with military force?

Jonathan Katz: I found no indication that he ever did any real soul searching on race. What we today call structural white supremacy was all around him, including a very overt white seal on his Marine collar. I think that race remained a major blind spot for him.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for sharing those glimpses from the complicated history of American empire. I appreciate that you traveled to each of the locations where Butler served and that, in addition to your archival research, you were on the ground and updated these stories with reports from these areas now. You learned that even if people in America don't know much about Smedley Butler and the Marines, certainly people in these far-flung sites of empire do.

Jonathan Katz: Yes. To a great extent this was a book about historical memory—the things that get remembered and the things that don't. The epigraph of the book is a Haitian proverb: “The one who deals the blow forgets. The one who carries the scar remembers.”

I wanted to go to all of the places where Butler and his Marines went. There's no replacement for getting out and being in a place and talking to people and then feeling the air and seeing what things look like. You can't really recreate through photos and letters, especially very old ones.

I also knew that the people in these places carry with them in some cases personal memories, and in other cases familial and communal memories of these moments that Americans don't know anything about for the most part. They are relegated to very specialized areas of academic and historical and military studies.

One of the most telling experiences that I had along those lines was in the Philippines on the island of Samar. I went to the village of Balangiga, which was a place where there was an enormous massacre of an occupying US Army unit by some local insurgents and villagers. Then there was a revenge massacre carried out by Littleton Waller and the Marines on orders to turn the island into a “howling wilderness.” That’s a place that people may know because, over the course of these reprisals, American troops took the church bells from the main church in of Balangiga and held onto them until they were returned in 2018. When I was there, I met with the mayor of Balangiga. I asked how he understood this period because, in the middle of Balangiga, there is an incredible monument with life size statues in gold depicting a diorama of the massacre of the American soldiers in 1901.

While I was there, the mayor told me about a pageant that the town puts on in which they recreate both the initial massacre of Americans and then the US revenge massacre of local people. I asked him how he looked at Americans today when he leaves his office every day and sees this statue and the town puts on this pageant. He talked about how he actually has family in the United States and he has a brother who was a US Marine. Because of the long period of US colonization in the Philippines, there's a very deep and very profound relationship between Filipinos and Americans that involves a lot of allyship and sympathy. I also asked him about the pageant and he said it is very important that we remember the past. And when I asked how he felt about Americans today, he said this is all in the past, and we can forget it. And then I said it sounds like you're saying that we have to remember and forget the past at the same time. He didn’t hesitate. He just said yes. And I think that captures the complexity and all of these issues, even for Smedley Butler.

America represented a lot of good things and some terrible events. The past is useful in some ways, and the past is destructive in other ways, and remembering these things can be destructive to other people's goals in the present, so there is a real negotiation between remembering and forgetting, and that reality infuses all of these circumstances right up until today.

Robin Lindley: And we’re still empire building in other ways now. And our democracy is under threat as demonstrated by the January 6th attack on the Capitol. And the Big Lie of the former president persists.

Jonathan Katz: Exactly. When I set out to write this book in 2016, I thought I would be writing about the roots of, of America's neoliberal empire in the early 20th century as we were about to experience the presidency of Hillary Clinton. Instead, history in our own time turned in a very different direction. All of the time that I was writing this book, the fault lines widened in America. It was only by doing this very granular and in-depth history that takes very seriously the material reality of both the reasons for and the practice of American imperialism in many different circumstances, that I could really see that the ties between the things that we normally relegate to either the realms of foreign policy or domestic policy. I could see how those things come together and the ways that wars and the other things that we do out there have this overwhelming tendency to always come back home.

We are seeing in America, at this moment, the effects of over a century of imperialism and dehumanization and using violence to get our way. We're seeing those things come back here. That was good for my book as a writer, but very bad for me and everybody else who is an American. And it reached its contemporary height on January 6th.

Robin Lindley: Thank you for your sharing your insights and thoughtful comments Mr. Katz. Gangsters of Capitalism is a groundbreaking and carefully researched examination of American empire. Congratulations again on the book and the glowing reviews.

Robin Lindley is a Seattle-based attorney, writer, and features editor for the History News Network (historynewsnetwork.org). His work also has appeared in Writer's Chronicle, Bill Moyers.com, Re-Markings, Salon.com, Crosscut, Documentary, ABA Journal, Huffington Post, and more. Most of his legal work has been in public service. He served as a staff attorney with the US House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations and investigated the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His writing often focuses on the history of human rights, conflict, medicine, art, and culture. Robin's email: robinlindley@gmail.com.

Spread the word