Do state courts have the power to interpret their own state constitutions? The Supreme Court could be poised to say “no” — at least when it comes to redistricting and election law.

Last week, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case Moore v. Harper in the coming fall term. In that case, Republican legislators in North Carolina are asking the court to overturn the state Supreme Court’s decision to throw out their gerrymandered congressional map and impose one of the court’s own.

Their argument rests on an extreme reading of the elections clause of the U.S. Constitution that posits that only state legislatures and Congress have the authority to decide how federal elections are run. Under this school of thought, known as the “independent state legislature” theory, state courts would no longer be able to intervene — even when a legislature violated the state’s constitution, as was found to be the case in North Carolina.

The independent state legislature theory sis fewer than 25 years old, and for most of its life, it’s been relegated to the fringes of academia. But it was widely promoted by former President Donald Trump and his allies as they attempted to first undermine — and then overturn — the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. And several Supreme Court justices have already suggested that they’re on board with the theory. During litigation over election laws in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin in 2020, Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch endorsed some version of the idea that state legislatures should have nearly unfettered power over how federal elections are run, and earlier this year, they said in an emergency-docket ruling that they would have ruled in favor of the North Carolina legislature.

If the Supreme Court sides with North Carolina Republicans in this case, it would have massive implications for election law. Depending on how the court rules, state courts might no longer be allowed to strike down legislatures’ proposed congressional maps for being gerrymandered. And if this happens, the way American elections are conducted would change in dramatic and destabilizing ways.

Thomas Wolf, deputy director of the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, said ruling for the North Carolina Legislature would be “stepping into an arrangement of election law that has never governed the country.” An extreme embrace of the theory by the Supreme Court would hand legislatures power over every aspect of how federal elections are run, to the exclusion of not only state courts but also possibly other state actors like governors and election administrators. “It would be a voter suppressor’s fever dream,” Wolf said.

Partisan gerrymandering could get much more extreme

First and foremost, if North Carolina Republicans prevail at the Supreme Court, state courts would lose some of their power to curtail gerrymandering — or maybe all of it. If the court accepts the independent state legislature theory but rules narrowly, it could allow state courts to overturn maps but not redraw them, according to Stephen Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “The idea is that there are certain things state courts can’t do,” Vladeck said. “So a state court could look at the legislature’s map and say, ‘Nope, try again.’”

But several more extreme paths are possible too. One option is that state courts might be barred from overturning maps based on vague sections of their state constitutions — like an equal protection clause — which would hamstring their ability to intervene in many states. Or the Supreme Court might simply rule that state courts can’t get involved in partisan gerrymandering disputes at all. That would directly contradict a 2019 ruling where the court’s Republican appointees said that federal courts couldn’t hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering,1 but they explicitly noted that state courts were still free to intervene. But the court is even more conservative than it was then, which means there might be a majority to turn around and limit state courts’ power.

That could mean a lot more work for the federal courts — exactly the kind of work that the justices said three years ago that they didn’t want federal judges to be doing. But it would also likely result in much more aggressive and unfair gerrymanders.

Over the past year, state courts have struck down congressional maps in not only North Carolina but also Maryland, New York and Ohio. If all of those rulings are invalidated, it would result in eight additional seats that lean at least 5 percentage points toward the legislature’s party, five fewer seats that lean at least 5 percentage points toward the opposition party and three fewer highly competitive seats.2 More importantly, it would also embolden legislatures in other states — knowing their maps wouldn’t be subject to judicial review — to draw more extreme gerrymanders in the future.

A ruling in favor of the independent state legislature theory could also jeopardize state redistricting commissions. A lot depends on the scope of the ruling, said Ethan Herenstein, counsel with the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, but embracing the idea that state legislatures have sole control over the redistricting process could imperil those commissions’ authority — even though the court upheld their constitutionality in 2015.

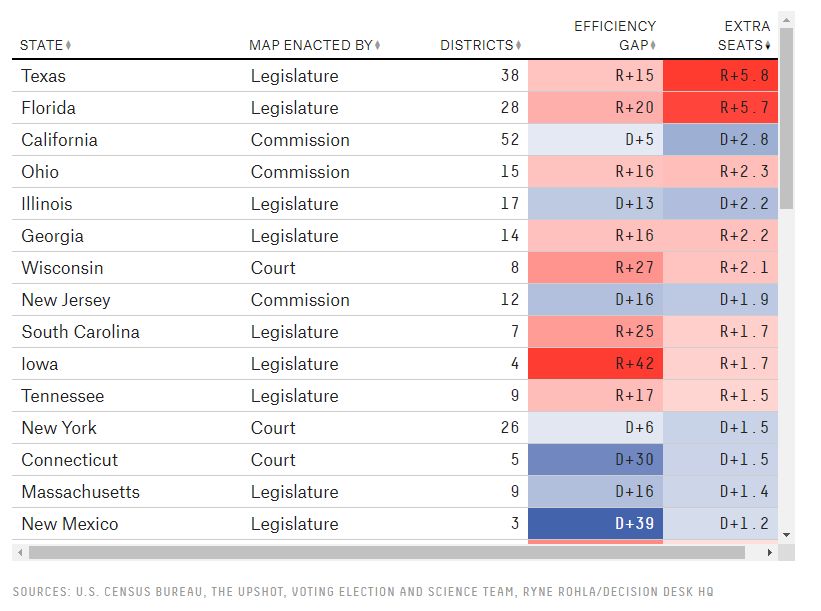

If the court eliminates redistricting commissions, gerrymandering would dramatically increase. During this past redistricting cycle, commissions enacted 10 congressional maps containing 125 congressional districts, and those maps were generally much fairer than legislatures’ maps: Commission-enacted maps of at least three congressional districts had an average efficiency gap of just 6 percentage points toward the party they favored, while legislature-enacted maps of at least three districts had an average efficiency gap of 16 percentage points.

In 2021-22, legislatures enacted very biased congressional maps

Who enacted each state’s new congressional map, what its efficiency gap is and how many extra seats it theoretically netted each party

But if those commission-enacted maps were suddenly rendered null and void, the court would actually give Democrats a major political boost. Out of those 125 districts, 84 are in states where Democrats would control the redistricting process, and 28-41 are in states where Republicans would (depending on whether governors still have veto power over new maps). Of course, these numbers may change after the 2022 elections, though probably not by much. Thanks in part to the way their maps are drawn, very few legislatures are expected to be competitive this year.

The country’s whole system for federal elections could change

But the impact wouldn’t stop at redistricting. The Constitution’s elections clause also covers every aspect of how federal elections are run. That includes the 56 voting restrictions passed since the 2020 election — laws that require ID in order to vote, discourage absentee voting, move up voter deadlines, cut early voting, purge voters from the rolls and ban giving food and water to voters waiting in line.

State courts are already hearing challenges to several such laws, but those could all get kneecapped if the Supreme Court fully embraces the independent state legislature theory. For example, in 2021, a state court struck down North Carolina’s voter-ID law, and the New Hampshire Supreme Court struck down a law imposing burdensome proof-of-residency requirements on people without an ID who register to vote within 30 days of an election. These laws might very well go back into effect after a ruling in favor of North Carolina’s Legislature in Moore v. Harper.

Similarly, courts would not be able to unilaterally change federal election laws in an emergency, like the Pennsylvania Supreme Court did in 2020 when it extended the deadline for absentee ballots to be received amid widespread delays in postal service. “If the state legislature says, ‘Polls close at 7 p.m.,’ and on Election Day, there’s a hurricane and the Supreme Court says, ‘Keep them open until 10,’ the legislature wins,” Vladeck said.

A sweeping ruling could also remove election officials’ discretion over how to administer elections, creating chaos on the ground. Right now, for instance, secretaries of state and local election officials make lots of decisions, big and small, so that elections run smoothly. But the independent state legislature theory could hand those decisions to legislators who often don’t work full-time and who have much less knowledge about the thousands of minute details that govern elections. “Elections are way too complex for legislators to legislate every single nook and cranny,” Herenstein said. But an extreme ruling in this case could, he said, “stop or slow state legislatures from even voluntarily sharing their power with election administrators.”

This would not only endanger programs that election officials have enacted of their own accord, like Colorado’s, Connecticut’s and Georgia’s implementation of automatic voter registration. It would also tie their hands in emergencies. For example, in 2020, officials in at least 41 states made executive decisions to loosen election regulations and encourage people to vote by mail amid the COVID-19 pandemic — everything from mailing voters absentee-ballot applications to counting COVID-19 as a valid excuse to vote absentee to extending voter-registration deadlines to setting up ballot drop boxes to postponing entire primaries. This may no longer be possible come 2024.

Some Trump allies have also argued that the independent state legislature theory empowers legislatures to appoint an alternate set of state electors — which, in 2020, could have overturned the presidential election. However, Leah Litman, a law professor at the University of Michigan, said that it’s important to remember that even the independent state legislature theory doesn’t mean state legislatures would be completely unchecked, because the U.S. Constitution would still apply. But she added that part of what alarms her about the theory is that it’s so unclear what embracing it would actually do. “It’s just kind of a mess,” she said of the theory. “We really don’t know what it would look like.”

We also don’t know what the court will do. Three justices — Thomas, Gorsuch and Alito — seem likely to embrace the theory and rule in favor of the North Carolina Legislature since they already said that’s what they thought the court should do. Another Republican-appointed justice, Brett Kavanaugh, wrote earlier this year that the issue was “important” and that “both sides have advanced serious arguments on the merits,” which suggests that he’s at least open to the idea. It’s far from clear that there are five votes to sign onto the independent state legislature theory — but at least some of the conservative justices seem to be on board already.

Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux is a senior writer for FiveThirtyEight.

Nathaniel Rakich is a senior elections analyst at FiveThirtyEight.

FiveThirtyEight Mission

We use data and evidence to advance public knowledge — adding certainty where we can and uncertainty where we must.

Values

The values we aspire to in our journalism …

- Empiricism — We base our stories on evidence. We use many different kinds of evidence — data, reporting, first-hand experience, academic research, etc — but we also interrogate it for underlying biases.

- Accuracy and completeness — Our primary standard is: “Is this accurate and does it present as complete a picture as possible?” and not some impossible “objectivity” or ideological centrism. We’re rigorous, and make every effort to test our hypotheses and assumptions. When the truth runs contrary to prevailing narratives we aren’t afraid to push back.

- Transparency — We show — and share — our work. That means we explain how we reached our conclusions, and whenever possible, share the data behind our stories. It also means we acknowledge that we bring our own biases and perspectives to the work. The data does not speak for itself; we’re doing the speaking, and that requires us to think and work through how our own perspectives might influence our journalism and try to account for them.

- Inclusivity — We make work that is relevant and accessible to a diverse audience. We make journalism for and about people of all identities — by race, gender, age, ability and background. We make journalism for readers, not for other journalists. And we make journalism for everyone, not just experts.

- Humility — Our understanding of the world is iterative. We aren’t afraid to say, “we don’t know,” or that our old analysis is now outdated, and with new evidence our argument has changed. When we’re wrong, we say we were wrong.

- Personality — Our journalists can bring their whole selves to their work. We share who we are and let the personalities of our journalists shine through.

Spread the word