film ‘All the Beauty and the Bloodshed’ Review: Nan Goldin’s Remarkable Life Gets a Towering Film Befitting It

Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2022 Venice Film Festival. Neon released the film to theaters in November. The film has been nominated for an Oscar -- Best Documentary Feature. The film will likely be streamed on streaming services after the Academy Awards in March.

That title. Even before it screened, “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” cast a shiver across the Venice Film Festival competition, sounding more like a line from a Yeats poem than the latest documentary from the director of “CITIZENFOUR.” The big news: the film lives up to it. Already a robust director, Laura Poitras has leveled up with a towering and devastating work of shocking intelligence and still greater emotional power.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is about the life and art of Nan Goldin and how this led her to found P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), an advocacy group targeting the Sackler family for manufacturing and distributing OxyContin, a deeply addictive drug that has exacerbated the opioid crisis. It is about the bonds of community, the dangers of repression, and how art and politics are the same thing.

The biggest compliment is that this film is worthy of Goldin, a woman whose words are as stark as her art, and whose art shows our most intimate and vulnerable selves. To this day, Goldin is known for her breakout photography collection “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” which includes joyfully candid images of the queer family she had at the Bowery in ’80s New York, self-portraits of sex with her boyfriend, and then her face with two black eyes after he later did his utmost to kill her.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” opens with shaky video footage from P.A.I.N.’s first piece of direct action in The Sackler Wing of The Metropolitan Museum in 2018. They chant “Sacklers lie, people die” and then lie on the ground feigning death. Goldin later reveals that she is inspired by the protest methods of ACT UP during the ’80s. It won’t be the first parallel that she or Poitras make between the AIDS and the opioid crises, and the politics of how certain people are left to die in America.

Poitras then takes us back to the suburban house where Nan grew up. Of her beloved older sister, Barbara, Goldin says, “She made me aware of the banal and deadening grip of suburbia,” speaking with a piercing affect that never lets up, not for a single answer, giving the narrative of her sprawling life the propulsive gait of a panther. For her part, Poitras understands the connections between events decades apart to such a degree that every detail included from a dysfunctional ’50s upbringing will later pay off in tens of different ways, so that this film achieves the monumental task of turning episodes from a life into one side of a perfectly intact shape.

We are told at this early stage that Barbara died by suicide. Nan then got the hell out of there, warned by doctors that if she stayed at home, the same fate would be hers. “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is dedicated to Barbara. The storytelling around Nan’s biography, her queer family, art, and what it looks like to take on the billionare Sackler family are so thoroughly absorbing that it is only at the end when everything circles back to Barbara, following the testimonies of family members who lost children to opioid overdoses, that one realizes that grief has been the emotional bedrock all along.

Poitras expertly moves from past to present, interviewing the investigative journalist, Patrick Radden Keefe, whose expose of the Sackler family in the 2017 New Yorker article “The Family Who Built an Empire of Pain” resulted in his house being staked out by a shady figure in an SUV. Poitras is on home turf when it comes to investigative storytelling and she digs out old adverts from after 1996, when OxyContin was launched in the states by the Sackler Company’s corporation Purdue Pharma. To combat the population’s fears they released reassuring commercials, and a man in a suit makes a direct address to the camera as he tells lies about OxyContin being non-addictive.

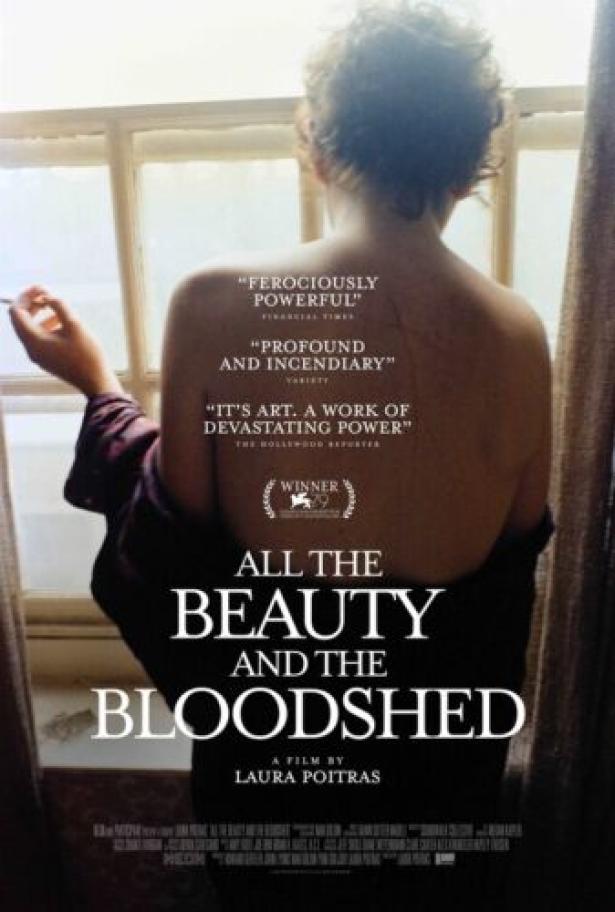

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”, Courtesy of Neon

Back once again into the past into the most exuberant part of Nan’s history: the discovery of her queer tribe, at first in Provincetown where she became friends with John Waters’ actress Cookie Mueller and then in The Bowery in New York. A galimorphory of photos and slides show birds of paradise, drag queens in feathers, young, beautiful, wild things in the bath, at shows, dancing, smoking, eating, fucking. The life-force running through these still images is electric and conjures up a time of freedom and possibility in the 1970s and ’80s, before AIDS, when hordes of people could bundle into a windowless loft space and live out their artistic and lifestyle impulses on the cheap.

When AIDS does start taking names, the film stays true, and locates Goldin’s attempts to express what was happening through her art in collaboration with the late, great David Wojnarowicz. His text on “The Killing Machine Called America” is leveled to evoke what was happening then and what is happening again, in a new way, now

We are given a whistle-stop tour through the subculture, with clips from films by Vivienne Dick and Bette Gordon and anecdotes from Tin Pan Alley, a bar where only women worked and Nan was “the dominatrix.” Each vignette comes with its own colorful detail or punchline. There is no dry box-ticking information, only vividness. It turns out that Goldin the orator cuts through the fugue of conformity with the same wallop as Goldin the photographer, and Poitras is there to give her the sharp edit that she deserves.

In the context of the breakdown of her relationship with the man who beat her up, Goldin offers a key: she “likes to fight.” Fighting is a motif of “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” — whether against a man who means physical harm, a family where no one tells the truth, or a pharma corporation intent on laundering its name through artistic donations.

As the film progresses, the line between art and politics melts away to nothing. P.A.I.N.’s protests belong in museums on artistry alone, nonetheless they occur with the very specific goal of getting museums to stop accepting Sackler money and to take down their names. The film embeds with the group as they discuss an old memo where the Sacklers say they want “a blizzard” of Oxy prescriptions to be released across America. For their next protest, they release a blizzard of prescriptions from the top floor of The Guggenheim down into its auditorium. It looks astonishing.

The event that led Goldin to found P.A.I.N. was her own overdose. She nearly died but came back, and stays clean with the help of a drug called buprenorphine that she maintains is more difficult for doctors to prescribe than OxyContin. I won’t spoil the confrontation that “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” suddenly offers up, except to say that, as it happens, Nan is holding the hand of her friend and fellow P.A.I.N. member, a tiny gesture that underlines how community has been the ballast that allowed this extraordinary woman to survive.

The documentary has been so rammed full of information, but in its last 15 minutes only the core principles flow, revealing a mighty coherence. The origin of the phrase “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is dropped in to offer a fitting and furious elegy for those on the other side. This is an overwhelming film.

Spread the word