Andrew Tripp Is an All-Star Union Organizer — And a Kick-Ass Cross-Country Coach, Too

Running coach Andrew Tripp greeted the high schoolers who trickled into Norwich University's field house with a hearty warning: A brutal workout was in store, starting with three laps around the indoor track — 600 meters at full speed.

Referring to the final turn, the U-32 coach said, "It's going to hurt very badly, but only for 15 seconds, OK?"

Normally, Tripp, who is 52, would have been running with them. But he had a cold, so he reverted to his race-day role of sideline encouragement, which he delivers in an emotional register that will stay imprinted in their amygdalae into adulthood.

"Amy, let's go, girl! Faster!"

The next group of runners stepped up to the starting line. "This is the 600. Violence, all right?" he cajoled. "This is not some middle-distance 'I'll save myself,' OK? Let's bite their head off, Ozzy Osbourne! You guys know Ozzy Osbourne, right?"

Indoor track is not a varsity sport for U-32 Middle & High School. Most of the athletes here were distance runners and Nordic skiers, not sprinters.

And yet the runners hustled and focused. Amid the herdlike thumping of feet, a young assistant coach from rival Harwood Union Middle & High School, Jake Pitman, marveled at the display of discipline: "They're all bought in. They want to be here. It's indoor track! It's not even regular track!"

Tripp's knack for motivating people has helped endurance athletes at U-32, a public school of 700 or so students from towns outside Montpelier, excel with head-turning consistency. They've won more than 30 state championships in Nordic skiing, track and field, and cross-country running, including seven consecutive titles for the boys' cross-country runners. In 2021, their streak earned Tripp an award as the top boys' coach in the country from the U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association.

Tripp likes to invoke ancient warriors and leads with Spartan intensity. But his sideline exhortations aren't as key to his coaching as the subtler techniques that Tripp has learned to apply from his primary occupation: union organizer. In both endeavors, the challenges are similarly steep — figuring out how to help disparate groups of people push themselves toward a finish line that will only be reached through stamina, sacrifice and shared purpose.

Establishing unions has gotten harder in the United States, where the proportion of unionized workers has been declining for 50 years. That's never deterred Tripp, who has honed the trade of high-stakes team building. He's worked on landmark campaigns in Vermont and more than 20 other states, organizing more than 100,000 people over the years. In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, he helped health care workers at a rural Pennsylvania nursing home take on the boss while many of them were infected with COVID-19.

Tripp played an important behind-the-scenes role last fall in the effort to organize nearly 5,600 minor-league pro baseball players, who for decades endured exploitative working conditions during their quests to make the big leagues. Their nationwide campaign defied long-held assumptions that minor leaguers were too itinerant and individualistic to band together and bite the head off Major League Baseball.

"I don't believe there's a better organizer in the country," said Larry Cohen, former president of the 700,000-plus-member Communications Workers of America, who chairs the board of Our Revolution, a political action group spun from Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-Vt.) presidential campaigns. "He works through other people, as the best organizers do. It's not charismatic organizing: 'If you want to be a hero, just follow me.' He's the opposite of that."

Grand Slam

In 2003, Colchester native and University of Vermont standout pitcher Jamie Merchant became one of the few Vermonters ever drafted by a major-league baseball team, but his selection was hardly a golden ticket.

Like most draftees, Merchant would never play in a major-league game. During his three years pitching in the Houston Astros' farm system, Merchant earned less than $10,000 per season, with which he was expected to pay rent and maintain his body at an elite caliber. He spent countless uncompensated hours on buses and worked a second job as a stonemason's assistant in the off-season. He accrued calories by eating leftover hot dogs from the stadium snack bar.

"You were treated horrendously," said Merchant, now 41, who runs a local carpet-cleaning business. "You felt at the time like that was the way it was. That was the price you had to pay if you wanted to play in the big leagues."

Back then, a fair deal for minor-league players seemed far-fetched. Even the powerful union for major leaguers, the Major League Baseball Players Association, had dismissed it. "The notion that these very young, inexperienced people were going to defy the owners, when they had stars in their eyes about making it to the major leagues — it's just not going to happen," former MLBPA president Marvin Miller told Slate in 2012.

In the ensuing years, as MLB tightened its grip, players began to challenge that assumption. They started speaking out, and their working conditions attracted wider attention. A pitcher-turned-attorney from New Jersey, Harry Marino, took charge of a small organization called Advocates for Minor Leaguers. Marino, whose career 2.13 earned run average hadn't been enough to secure a big-league promotion, recruited players into activism through Instagram. Within months, MLB announced it would provide housing to minor-league players.

Energized, and backed with some MLBPA funding, Marino's group decided to explore a minor-league union. One problem: "None of us had any union organizing experience," Marino said. One of the group's founders, labor and racial justice activist Bill Fletcher Jr., recommended he contact Tripp for help, Marino said.

Tripp, an independent consultant at the time, said he saw in Marino someone who had the chops to spearhead an ambitious drive.

"As an attorney — an attorney who wasn't corroded by his legal training — he understood intuitively that organizing players was the only power that the ballplayers had," Tripp said.

Beginning in fall 2021, Tripp served as adviser to Marino, as a strategist and a sort of organizers' organizer, training the handful of former players who joined as field organizers. Advocates for Minor Leaguers formed a player steering committee, and Tripp and Marino went on a spring-training tour to Arizona and Florida to meet with more athletes. Tripp, who is fluent in Spanish, helped make inroads with players from Central America. Mostly, he showed the player-organizers how to approach the delicate, methodical work of building trust among players across more than 100 clubhouses.

Even with an effective organizing network, the players were uniquely vulnerable. An aggressive opposition campaign by the deep-pocketed league could crush their shoestring effort. "So we had to back the league off," Tripp said.

Public awareness was one prong of the strategy that Advocates for Minor Leaguers devised. Congress was another. The league, in 2021, had cut ties with 40 of its affiliate teams, including the Vermont Lake Monsters, eliminating hundreds of jobs, many of them in communities that had helped pay for the stadiums. (The Lake Monsters were reconstituted as a collegiate summer team; its players today are unpaid.)

Congress had historically done MLB's bidding, but now the players saw lawmakers as an important ally. Sen. Sanders announced a push to end a long-standing antitrust carve-out that had allowed Major League Baseball to suppress wages and control teams in ways that most businesses could not. The chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) planned hearings on the question. Key Democratic and Republican senators started talking publicly about the treatment of minor leaguers.

Time, however, was not on the players' side. The minor-league workforce would disperse during the off-season and rosters would change, weakening the player relationships needed to win majority support for a union. Players could hold elections club by club, but a patchwork process could allow team owners to more easily push back. Pursuing a league-wide vote, meanwhile, was an all-or-nothing gamble.

Confident in the breadth of their support, Advocates for Minor Leaguers went for the league-wide approach. When the campaign went public last August, it took barely two weeks for a majority of players to sign cards saying they wanted a union. The once-skeptical MLBPA had agreed to represent the players, leaving the league with two options: force a contested election, administered by the National Labor Relations Board, or agree to recognize the new union and negotiate with players. The league acquiesced.

The players' triumph surpassed any victory on the field, Josh Hejka, a pitcher for the Binghamton, N.Y., Rumble Ponies, told Sports Illustrated. "It felt like it overcame the individuality of pro ball to the point where there was a collective excitement, collective celebration," he said, "and that's something I hadn't really felt — that raw an emotion — since college."

The challenges the players overcame weren't unlike those faced by other workers who seek to unionize, Tripp said. But the minor-league drive differed in one respect. "It went almost exactly according to plan," he said.

'Organizing the Unorganized'

1995 was a pivotal year for America's labor movement. With union membership steadily dropping, progressive insurgents staged a revolt at the country's largest union federation, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, to push for a more aggressive response. The incoming AFL-CIO president, John Sweeney, set union expansion as his top priority through his mantra to "organize the unorganized."

Tripp was on board. Then a graduate student studying economic history at the University of Chicago, he had come to believe that a strong labor movement was the foundation for all progressive social change. "It's fundamentally about small- 'd' democracy. Do you get to vote on what you get paid? Or does someone get to just tell you?" he said.

Tripp had learned at a young age the ethic of never crossing a picket line. His father, a Harvard University-educated physician, was a New Deal Democrat who had served in the Peace Corps in Cameroon and Nigeria. Tripp grew up in Washington, D.C., then attended Harvard himself.

At a time of rapid globalization and free-trade Clintonomics, Tripp was studying the policies of the late Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas, who seized the assets of foreign oil companies during a labor dispute. He came to loathe the culture at the exclusive institutions he'd attended, seeing them as training grounds for the "world's elite."

"I wanted no part of that team," Tripp said. "I understood them to be doing bad work. Not ambiguous work, not 'It's complicated' work, not gray-area work. Bad work."

Tripp started an organizing drive among University of Chicago graduate students in 1995 and later traveled to California to work on an ambitious but unsuccessful campaign by the United Farm Workers to unionize strawberry pickers, most of whom were immigrants. He never returned to graduate school.

Some of Tripp's earliest campaigns as a field organizer were waged at nursing homes, including in central Vermont, where he and his partner, Rebecca Plummer, moved in 1999 after she got a job as an attorney at Vermont Legal Aid. He took a position with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America, or UE, helping nursing assistants and service workers form a union at Berlin Health and Rehabilitation in Barre. They won a fiercely contested union election in 2000, making them the only unionized nursing home workers in Vermont.

Kimberly Lawson, a union staffer with the UE, was initially skeptical of Tripp and his Ivy League background, but he showed he could earn the trust of the older, mostly female nursing home workers, she said. Tripp also proved adept at identifying which workers could become leaders among their coworkers — a crucial skill for organizers, Lawson said, especially in private-sector workplaces, since union officials typically can't access company property.

A nurse sympathetic to the plight of the home's nursing assistants persuaded licensed nursing assistant Laurie Gomo to join the cause, Gomo recently recalled. "I trusted her; therefore, with her backing up Andrew, I felt he was OK," Gomo said. She handed out union flyers during the drive.

Being a white man who wears Carhartts comes with certain advantages in Tripp's line of work, where he's seen employers use photos of a gay organizer to divide workers. These days, Tripp, pale and sinewy, wears beat-up running shoes, U-32 jackets and Bernie beanies, from which curls of dark hair peek out. He converses with a disarming openness that makes it easy to envision even a stranger sharing confidences with him. Tripp might also be genetically predisposed to forthrightness, as when, during one interview for this story, he suggested that Seven Days publish an article about bass fishing, one of his hobbies, figuring that the paper's middle-class readers would enjoy reading about something they saw as "authentically redneck."

Tripp's zealousness for the work aids in the organizer's fundamental task: getting workers to take personal risks for the benefit of their group. Those consequences can be particularly severe in the United States, where most employers can terminate workers without cause. Though it's illegal to fire someone because they're involved in organizing, enforcement is "exceedingly weak," Tripp tells workers. "You don't hide that."

Vermont, despite its political bent, historically has been no easier for workers seeking to organize. Only 13 percent of its workers were represented by a union last year, according to federal data. The Committee on Temporary Shelter, a homeless shelter in Burlington, defeated workers in a contested election in 2007. An ambitious effort to create a union for all of Montpelier's downtown service workers, led by the UE and the Vermont Workers' Center, fizzled amid criticism that it was too confrontational for small-town Vermont, even though the National Labor Relations Board found that one of the businesses had violated workers' rights during the drive. When nurses at the hospital now known as the University of Vermont Medical Center tried to unionize in 1998, the Burlington Free Press, in an editorial, urged them to vote no.

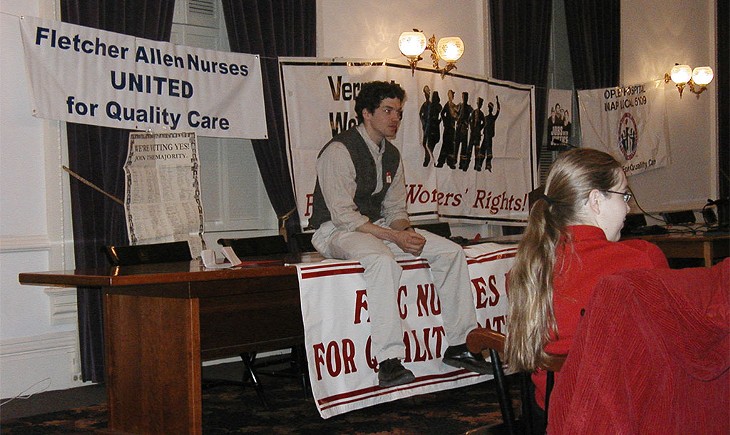

The Berlin Health and Rehab union fell apart after several years. But the UVM Medical Center nurses tried again, successfully, in 2002. Tripp worked that campaign and, alongside the nurses, led the negotiations for their first contract.

"I just real quickly felt like he was a brother to me," said Mari Cordes, one of the nurse-organizers and now a Democratic state rep from Lincoln. "Not just in the union sense, but like a brother. He had my back."

The nurses' first contract secured better pay and staff-to-patient ratios and was a signal moment in the state's labor history. During bargaining, Tripp and the nurses sat opposite the hospital's hired attorney, an ace named Peter Robb from Burlington's Downs Rachlin Martin law firm. Robb, whose surname, Tripp admits, was "rhetorically very useful," would later be appointed in 2016 as the National Labor Relations Board's general counsel — the country's chief enforcer of federal labor law — by then-president Donald Trump.

Extended Stay

Tripp spent 17 years working full time on contract campaigns, strikes and new union drives, many of which were grueling affairs. He knocked on workers' doors, and some of them slammed those doors in his face. He slept in extended-stay motels and fielded late-night calls from workers who had just learned they were being deported. Fellow organizers typically would unwind each night at the bar. Tripp, who used to run ultramarathons, would go for long jogs.

Tripp's tenacity occasionally got him into trouble. Security guards once broke up a shouting match between Tripp and former hospital lobbyist Steve Kimbell on the Statehouse steps in 2004. Kimbell tried to leverage the encounter with lawmakers, urging them to vote against a union-supported bill to grant whistleblower protections to nurses on the grounds that their advocate had resorted to "physical intimidation." Tripp told Seven Days columnist Peter Freyne that Kimbell had called one of the union nurses a liar.

"It's a strength and a weakness that I take things exceedingly seriously," Tripp said. "It's not just business for me. I mean, I know it is for those guys. I've learned to be able to be civil. It's taken a long time."

Tripp started chasing organizing campaigns "like a junkie," he said. He worked several years for Service Employees International Union, then one of the most aggressive unions anywhere when it came to new organizing, and later became executive director of the Vermont chapter of American Federation of Teachers, or AFT Vermont. The victories sustained Tripp, but so did smaller encounters. Pro-union workers in Tripp's first campaign, at a nursing home in Vestal, N.Y., lost a bitter election by just a couple of votes. Following the result, Tripp said, one of the workers revealed that she'd left her abusive husband during the union drive "because we learned to stand up for ourselves."

Most labor organizers don't tend to last long. Tripp eventually came to exist in a state of constant dread. He feared the next "scorched earth" fight that could ignite at any time. "Even just talking to you about this, my cortisol levels are way up," he said. It started to make him sick.

"It took a real kind of health breakdown for me to realize that, like, well, if you die at 42, you can't do any useful work," he said.

In June 2012, bedridden with pneumonia and with the adoption of his and Plummer's second child pending, Tripp accepted that he needed to slow down. He decided to carry on his organizing work as a consultant, at a safer distance from the "sharp end of the spear."

Commitment

That summer, Tripp saw a "help wanted" ad for an assistant cross-country coach for U-32 and jumped on it. The gig was sweet. The team's head coach, Mark Chaplin, is a local legend who had been coaching since shortly after U-32 opened in 1971. Chaplin established a team ethos by running with his athletes during practices and, later, bicycling alongside them. He retired as a chemistry teacher last year but still helps coach.

Even Chaplin was taken aback by the way Tripp applied his organizing frame of mind to high school coaching. Tripp would show up to the weight room and basketball games to prospect for new recruits, "then talk to them after the game, or send them letters, or get their teammates who are already on the track team to talk to them and try to talk them into doing it," Chaplin said.

Tripp started holding summer training camps at his family's cabin in Craftsbury, where runners sleep in tents and share chores. During the retreats, he counsels students about their goals and training plans. Andrew Crompton, a runner who graduated in 2019, said Tripp required him to log at least 200 miles during the summer to gain admittance to the camp.

Running, in Tripp's eyes, is the most "democratic" sport, especially at the high school level, as Tripp sometimes reminds affluent parents who ask for recommendations on which shoes will make their child faster. "I'm like, look, they're a novice runner. Basically, they need to run to Chicago over the next five to six months. And call me when you get there." The key is commitment, and Tripp sees coaching as a matter of convincing athletes to do the necessary, year-round, frequently unpleasant work. He's direct with athletes when he thinks they aren't pulling their weight, which leads to occasional complaints from parents.

"There are times when it helps to have me around to soothe the ruffled feathers," Chaplin said.

"Andrew came in knowing how to coach kids to get really good and reach their full potential," said former Nordic skier Emma Curchin, "which is challenging, I think, with middle school and high schoolers, because not everybody wants to have a sport be a very serious thing."

At U-32, endurance sports are not treated as individual events. "You're running every day for your team," Crompton emphasized. In 2021, the boys' cross-country team became just the second from Vermont to ever win the New England regional championships, where they bested a powerhouse private school from Rhode Island. A final-stretch push by the squad's fifth-fastest runner, then-junior Sargent Burns, clinched the win. "We both cried when the scores were announced," Tripp told a reporter after the race.

Athletes impart the program's collectivist approach to their younger peers, which has proven key to U-32's recurring success.

"He kind of established these expectations, and since then, the leaders each year have really set forth those expectations," Crompton, now a captain on the UVM track team, said. "So it's kind of a self-running machine."

Passing It Down

More than 70 percent of Americans say they approve of unions, the highest level since 1965, according to a recent Gallup poll. Unions have made inroads at Amazon, and workers at more than 250 Starbucks locations have organized in the past two years despite of vigorous opposition by the company.

In the past few years in Vermont, more than 1,000 UVM staff voted to form a union, and VTDigger.org agreed to recognize its employees' new union. Last month, more than 2,200 of the lowest-paid workers at the UVM Medical Center voted to join the union that the hospital's nurses formed two decades ago — the largest private-sector union mobilization in recent state history.

The renewed organizing energy has yet to reverse unionism's decline as a broad economic force; the proportion of American workers in unions dipped to its lowest point on record last year, 10 percent. But it suggests collective action may be gaining purchase among a new generation of workers who are trying to find their place in an economy that doesn't seem to have their future in mind.

Former Communications Workers of America president Cohen sees the minor-league players' union as representing an important way forward. The win showed the power workers can wield when they organize simultaneously across an entire industry, an approach that has become rare in the U.S. Only such broad-based organizing will be able to tilt economic power back toward workers, Cohen said.

James Haslam, who for years ran the Vermont Workers' Center, a labor rights organization, and cofounded the economic and social justice group Rights & Democracy, said Tripp introduced him as a young organizer to the adage that "the boss is only half the problem." It's helped motivate his work ever since.

Haslam described Tripp as a practitioner of methods that have been passed down across generations of working people. In Vermont, small numbers of organizers have helped to "keep the torch lit" over time, Haslam said, so that when new groups of workers are ready to unionize, they have the tools and the confidence to succeed.

As a seventh grader at U-32 a decade or so ago, Curchin was among Tripp's first group of Nordic skiers. She can still hear his voice in her head imploring her to "double pole, faster, faster!" She discovered labor organizing during college in Minnesota and now, at 23, works for an economic justice think tank in Washington, D.C. She is contemplating eventually getting into organizing work full time.

Last month, Curchin attended a public podcast recording in the city featuring interviews with an Amazon organizer and the minor-league organizer Marino, who now works for the MLBPA. During the event, Marino credited Tripp for his behind-the-scenes work.

Curchin went up to Marino afterward to let him know: "That's my high school cross-country coach."

The original print version of this article was headlined "The Long Run | Andrew Tripp is an all-star union organizer — and a kickass cross country coach, too"

Spread the word