MADISON, Wisconsin — Spring elections in Wisconsin are typically low turnout affairs, but in April, with the nation watching the state’s bitterly contested Supreme Court race, voters turned out in record-breaking numbers.

No place was more energized to vote than Dane County, the state’s second-most populous county after Milwaukee. It’s long been a progressive stronghold thanks to the double influence of Madison, the state capital, and the University of Wisconsin, but this was something else. Turnout in Dane was higher than anywhere else in the state. And the Democratic margin of victory that delivered control of the nonpartisan court to liberals was even more lopsided than usual — and bigger than in any of the state’s other 71 counties.

The margin was so big that it changed the state’s electoral formula. Under the state’s traditional political math, Milwaukee and Dane — Wisconsin’s two Democratic strongholds — are counterbalanced by the populous Republican suburbs surrounding Milwaukee. The rest of the state typically delivers the decisive margin in statewide races. The Supreme Court results blew up that model. Dane County alone is now so dominant that it overwhelms the Milwaukee suburbs (which have begun trending leftward anyway). In effect, Dane has become a Republican-killing Death Star.

“This is a really big deal,” said Mark Graul, a Republican strategist who ran George W. Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign in Wisconsin. “What Democrats are doing in Dane County is truly making it impossible for Republicans to win a statewide race.”

In isolation, it’s a worrisome development for Republicans. Unfortunately for the larger GOP, it’s not happening in isolation.

In state after state, fast-growing, traditionally liberal college counties like Dane are flexing their muscles, generating higher turnout and ever greater Democratic margins. They’ve already played a pivotal role in turning several red states blue — and they could play an equally decisive role in key swing states next year.

One of those states is Michigan. Twenty years ago, the University of Michigan’s Washtenaw County gave Democrat Al Gore what seemed to be a massive victory — a 60-36 percent win over Republican George W. Bush, marked by a margin of victory of roughly 34,000 votes. Yet that was peanuts compared to what happened in 2020. Biden won Washtenaw by close to 50 percentage points, with a winning margin of about 101,000 votes. If Washtenaw had produced the same vote margin four years earlier, Hillary Clinton would have won Michigan, a state that played a prominent role in putting Donald Trump in the White House.

Name the flagship university — Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Ohio, Texas, Virginia, among others — and the story tends to be the same. If the surrounding county was a reliable source of Democratic votes in the past, it’s a landslide county now. There are exceptions to the rule, particularly in the states with the most conservative voting habits. But even in reliably red places like South Carolina, Montana and Texas, you’ll find at least one college-oriented county producing ever larger Democratic margins.

The American Communities Project, which has developed a typology of counties, designates 171 independent cities and counties as “college towns.” In a combined social science/journalism effort based at the Michigan State University School of Journalism, the ACP uses three dozen different demographic and economic variables in its analysis such as population density, employment, bachelor’s degrees, household income, percent enrolled in college, rate of religious adherence and racial and ethnic composition.

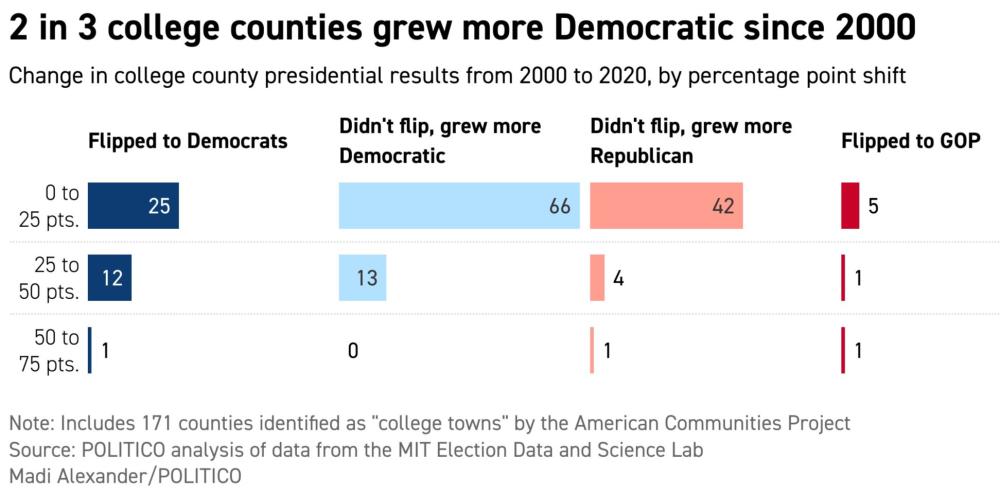

Of those 171 places, 38 have flipped from red to blue since the 2000 presidential election. Just seven flipped the other way, from blue to red, and typically by smaller margins. Democrats grew their percentage point margins in 117 counties, while 54 counties grew redder. By raw votes, the difference was just as stark: The counties that grew bluer increased their margins by an average of 16,253, while Republicans increased their margins by an average of 4,063.

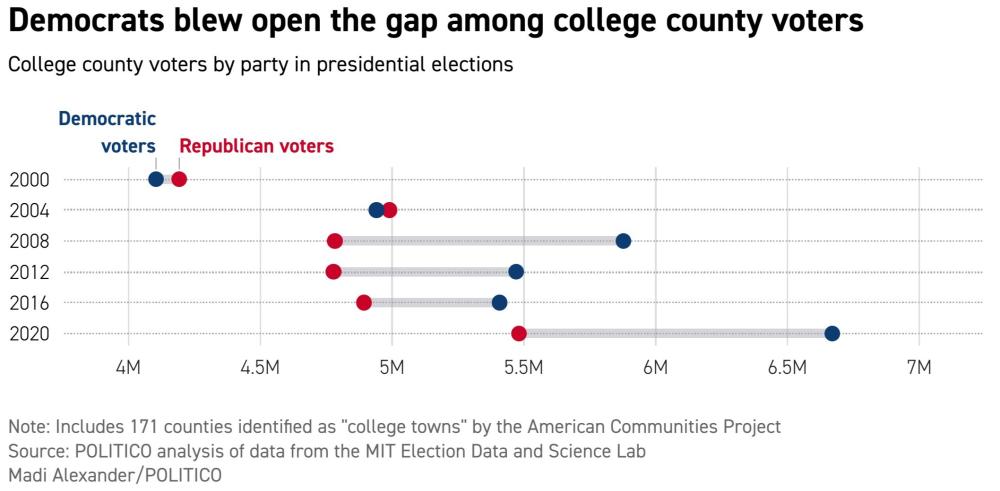

Back in 2000, the places identified as college towns by ACP voted 48 percent to 47 percent in favor of Al Gore. In the last presidential election, the 25 million who live in those places voted for Joe Biden, 54 percent to 44 percent.

Many populous urban counties that are home to large universities don’t even make the ACP’s “college towns” list because their economic and demographic profiles differentiate them from more traditional college counties. Among the missing are places like the University of Texas’ Travis County, where the Democratic margin of victory grew by 290,000 votes since 2000, and the University of New Mexico’s Bernalillo County, where the margin grew by 73,000 votes. The University of Minnesota’s Hennepin County has become bluer by 245,000 votes.

North Carolina offers a revealing snapshot of a state whose college towns have altered its electoral landscape. Five of the state’s nine counties that contain so-called college towns have gone blue since voting for George W. Bush in 2000. Back then, the nine counties together netted roughly 12,000 votes for Bush, who carried the state by nearly 13 percent. Twenty years later, those numbers had broken dramatically in the opposite direction — Biden netted 222,000 votes from those counties. He still lost the state, but the margin was barely more than 1 percent.

There’s no single factor driving the college town trend. In some places, it’s an influx of left-leaning, highly educated newcomers, drawn to growing, cutting-edge industries advanced by university research or the vibrant quality of life. In others, it’s rising levels of student engagement on growing campuses. Often, it’s a combination of both.

What’s clear is that these places are altering the political calculus across the national map. Combine university counties with heavily Democratic big cities and increasingly blue suburbs, and pretty soon you have a state that’s out of the Republican Party’s reach.

None of this has gone unnoticed by the GOP, which is responding in ways that reach beyond traditional tensions between conservative lawmakers and liberal universities — such as targeting students’ voting rights, creating additional barriers to voter access or redrawing maps to dilute or limit the power of college communities. But there are limits to what those efforts can accomplish. They aren’t geared toward growing the GOP vote, merely toward suppressing Democratic totals. And they aren’t addressing the structural problems created by the rising tide of college-town votes — students are only part of the overall phenomenon.

“The data sure seem to suggest younger voters are leaning much more Democratic in recent years and, perhaps more concerning for the Republicans, the GOP seems to be struggling more broadly with college-educated voters. In the longer term, that may mean these voters may stay Democratic — or at least stay Democratic longer than they might otherwise,” says Dante Chinni, director of the ACP. “In addition, polls show Republicans are increasingly distrustful of higher education institutions. That probably doesn’t help in the longer term either.”

‘The Ecosystem is Churning and Churning Right Now’

For much of the 20th century, the area surrounding Fort Collins, home to Colorado State University, was a Republican stronghold. Larimer County, with its farming and ranching heritage, was the kind of place that voted Democratic only under extreme circumstances — like during the landslide elections of 1936 and 1964, or in 1992, when the presidential vote was splintered three ways. Today, however, after Biden won Larimer in a 15-point blowout in 2020, the real question: Just how deep is the county’s shade of blue?

Larimer’s political evolution is in large part a story of how the economic, cultural and political forces radiating out of university communities can alter the political complexion of a red county — and ultimately a state.

Since 2000, Colorado State has experienced an extended growth spurt that has seen enrollment expand by more than 7,300 students. The number of tenured faculty has grown, the number of university employees has grown and the campus itself has seen $1.6 billion in capital investment in everything from residence halls to research centers to a new campus stadium.

More college students and more faculty tend to be a recipe for more Democratic votes. But there are also larger forces at work. Larimer County grew by 19 percent in the 2000s, and then by another 20 percent in the most recent census, with over 100,000 new residents arriving over the past two decades. That surge of newcomers flocked to the area for its high quality of life and dynamic economy — and CSU plays a role in sustaining both. Aside from providing Fort Collins with big-city amenities, it partners and collaborates with nearby industries and the major federal laboratories and research centers that are clustered in Colorado.

The school — with its expertise in vector-borne infectious disease, veterinary medicine, atmospheric science, clean energy technologies and environmental science — aggressively commercializes its research. A private, not-for-profit corporation, legally separate from the university, exists solely to spin technology out of the university and into the private sector. As a result, more than 60 startups based on CSU intellectual property have launched over the past two decades.

“As the university grows and we bring in superstar faculty and researchers as our research portfolio and whatnot continues to grow,” says Amy Parsons, president of Colorado State, “then they’re expanding and creating new technologies, new spinoff companies out into the community that’s bringing in more jobs and people and diversity, and so that’s the ecosystem that is churning and churning right now.”

While the newcomers — many of whom have relocated to the Fort Collins-Loveland metro area from elsewhere in Colorado, but also disproportionately from states like California, Arizona and Texas, according to Census data — have helped Democrats achieve parity with Republicans in terms of voter registration, the bigger story in Larimer County is the explosive growth in the number of unaffiliated voters. Between 2011 and 2023, the number of unaffiliated voters grew by close to 200 percent. Today, it is the most dominant voting bloc in the county — close to half of all voters in the county are now registered as unaffiliated — and they are casting votes for Democratic candidates.

“Colorado, like the West, [has an] independent streak, a lot of unaffiliated voters,” says John Kefalas, a CSU graduate who also served as an adjunct faculty member and in 2018 became the first Democratic county commissioner since 2004. “But those unaffiliated voters, based on our experience, tend to lean toward Democratic or tend to lean toward more moderate or progressive.”

The national realignment of politics along cultural and educational lines is also playing a role. Larimer ranks as one of the most educated counties in Colorado, which itself ranks among the most educated states in the nation. Even if newcomers aren’t registering as Democrats, many possess the traits associated with a Democratic voter profile — environmentally conscious, closely attuned to climate change issues, white and college-educated. As Larimer and the other high-population areas along the state’s urbanized Front Range corridor have drifted leftward, so has the state: Democrats now hold all the levers of power in Colorado, including the governor’s office and the legislature.

The state’s two biggest college counties have led the way. Back in 2000, Colorado was a red state that had voted for Republican nominees in eight of the preceding nine presidential elections. But since 2008, when Larimer first flipped from red to blue, the state has firmly been in the Democratic column. Between the 2000 and 2020 presidential elections, in Larimer and Boulder County, home to the University of Colorado, the Democratic vote grew by 169,000 votes. The Republican vote, by comparison, grew by just 21,000 votes.

Virginia has followed a similar path. The American Communities Project lists 18 counties and independent cities as college towns there; nine of them have flipped from red to blue over the past 20 years. Just one, the city of Norton in the southwest corner near to UVA’s College at Wise, has flipped the other way — by less than 1,000 votes. Virginia’s governor is Republican, but like Colorado, the state voted Democratic in 2008’s presidential race and hasn’t looked back.

‘A Place Where People Tend to Find Like-Minded People’

With their reputation for livability, college towns exert a magnetic pull that draws new residents from other states. Often, these new residents are fleeing more conservative locations, and their arrival has the effect of intensifying the liberal bent of the surrounding area.

Asheville in western North Carolina is one of those places.

Though considerably smaller than some of the other college towns in the state, Asheville’s Buncombe County has added just over 66,000 residents since 2000 and grown a robust 12 percent in just the last decade. Over that period, those new residents have played a key role in Buncombe’s evolution from a red county that gave George W. Bush a comfortable 54-45 victory to a blue stronghold Biden won by a 21-point margin.

Though it’s listed as a college town by the ACP — it’s home to roughly 3,000 University of North Carolina Asheville students — few here think of it that way. Asheville is a popular tourist town, a hub for arts and music and a counterculture haven in the scenic Blue Ridge mountains, and it’s the new permanent residents who are having the impact on the county’s political complexion.

“Asheville is known as a bring-your-own-job city,” explains Nick Hinton, a local real estate agent who’s originally from Los Angeles and moved to Asheville a decade ago. “We’re not known to have a plethora of career-type jobs available. Those types who either have a job or can telecommute or feel like opening up a business, that’s who seems to be drawn to this area.”

Many are millennials — the baby boomers who come here to retire, Hinton notes, tend to be less politically motivated. A healthy portion move here from elsewhere in the state but Florida, Illinois and the Northeast are also sending a steady stream.

Jeff Rose, the county’s Democratic Party chair, notes that many of the newcomers are “climate refugees” highly attuned to environmental and sustainability issues. “I’ve met numerous people who moved here from California to try and get away from constant forest fires and things like that,” he says. “If you’re ideologically interested in the issues that arise from climate change, there’s a lot of people here that are doing that kind of work, whether it’s groups that do river clean-ups, groups that are focusing around the Collider, which is an innovation center for sustainability — there’s a number of solar companies and things like that in the area. …This is a place where people tend to find like-minded people.”

Buncombe’s intensifying leftward shift has a strong self-sorting element to it and it’s not alone nationally.

“We’ve seen this pattern in the last 10 years across the country,” says Democratic state Rep. Lindsey Prather, a UNCA graduate who represents an Asheville-area district. “People are increasingly looking at the partisan leaning of a community when they’re deciding where to move. It used to be, well, I got a job there or my family’s there.”

Just as in Colorado’s Larimer County, the newcomers are registering as unaffiliated but largely voting Democratic. Today, a plurality of Buncombe County voters are registered as unaffiliated — and there are nearly twice as many unaffiliated as there are registered Republicans. Yet the effect has been to amplify Asheville’s traditionally liberal politics and push the surrounding county leftward. In 2020, Asheville elected a progressive, all-female city council. Last year, the Buncombe County commission ousted its lone remaining Republican.

So far, the growing Democratic margins in Buncombe, the Research Triangle — which is home to three major research universities — and other college counties haven’t been enough to turn the state blue, though many Democrats continue to view North Carolina as close to a tipping point. Biden came close in 2020, losing by just over a percentage point, but Democrats haven’t won a Senate race in North Carolina since 2008 and have won a presidential race just once here since the 1970s.

“Everything the Republicans are doing now in this legislative session will come back to haunt them in places like Buncombe County,” says Democratic state Sen. Julie Mayfield, referring to a slew of contentious measures including a 12-week abortion ban and education policies that would make it easier to prosecute librarians and school employees for displaying materials deemed harmful to minors, pursued by the GOP majority in Raleigh, “just like what happened in Wisconsin.”

The college town phenomenon is so strong it has Democrats daring to wonder if they might one day flip a solidly red state such as Montana. It seems implausible given the shellacking that Democrats endured in 2020 when the party suffered a devastating across-the-board defeat, leaving just one statewide Democratic official in office, Sen. Jon Tester.

But the state has a long history of ticket-splitting — Democrats held the governorship from 2005 through 2021; in 2008, Barack Obama came within 12,000 votes of winning here. And if you look at the growth in Montana’s two big college counties, Missoula, which is home to the University of Montana, and Gallatin, which is home to Montana State University, you see what gives Democrats hope.

Gallatin, which serves as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, has nearly doubled in population since 2000, fueled by rising enrollment at the university, out-of-state migrants and the emergence of Bozeman as a technology hub. And over that period, it’s gone from a 59-31 Bush county to a 52-45 Biden county. Between Gallatin’s boom and Missoula’s more modest growth, the two Democratic beachheads now account for roughly a quarter of the statewide vote — up from about 20 percent in 2000. Many of the new migrants to Bozeman are Californians. But they are also moving in from the Denver suburbs and from big cities across the West — Seattle’s King County, Phoenix’s Maricopa County and Las Vegas’ Clark County.

“I’ll never own a house in Bozeman. Not unless I get some kind of crazy promotion,” Kortum laments. “The housing prices have tripled in the last 10 years. The pandemic exacerbated that by driving a lot of fresh retirees to retire in Montana.”

As Bozeman grapples with its housing crisis, Flathead County, a Republican stronghold near Glacier National Park, has drawn an influx of more conservative newcomers in recent years, recently overtaking Gallatin as the fastest-growing county in Montana. While there’s no significant college presence in the county, at the rate it’s growing it could surpass Missoula and Gallatin counties in population by the end of the decade.

“Bozeman is blue,” says Julia Shaida, the Gallatin County Democratic Party chair, “if you can afford to live here.”

‘Ever Greater Turnout, Producing Ever Greater Margins’

Growth is politically meaningless if new residents don’t become voters. In college towns, the get-out-the-vote efforts have converted newcomers into electoral muscle.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the fastest-growing county in Wisconsin.

Between 2010 and 2020, Dane County grew by 15 percent, adding close to 75,000 new residents. It didn’t take long for the political implications of that surge to become apparent. Between 2016 and 2020, the county’s raw vote grew by 11 percent and Democratic performance began ratcheting upward in statewide races. Even with the GOP’s pronounced recent gains in rural Wisconsin, if Dane County voters continue to turn out at exceptionally high levels and continue to deliver landslide Democratic margins, Wisconsin’s days of being a swing state are numbered.

“The superpower of Dane County is ever greater population with ever greater turnout producing ever greater margins,” says Ben Wikler, the chair of the state Democratic Party. “Dane County turnout helps create a buffer against potential growth in Republican turnout elsewhere in the state.”

And Dane County has one of the nation’s most effective local party organizations. “It’s not a very sexy story. It’s a lot of hard work that we’re doing over a long period of time,” says Alexia Sabor, Dane County Democratic chair.

“The county party helps to organize a network of 20 neighborhood grassroots action teams. We fund them, we provide them with offices during election seasons, we give them money for websites, Mailchimp [an email marketing platform], volunteer recruitment events, volunteer thank-you events, whatever supplies they need — paper, printers, lighting — to run their team,” Sabor says. “We’re doing this every month of the year, whether or not there’s a big election coming. And we’ve been doing it for the last five years.”

In an interview at a Madison pub, Sabor radiates focus and intensity as she talks about the nuts and bolts of campaigning. She and other local party members fully recognize statewide elections now hinge on a turbocharged local performance, one that delivers votes not only from the deep blue precincts of Madison but also from the smaller and more politically competitive suburban cities, towns and villages that surround it.

She notes matter-of-factly that other county Democratic parties had spring galas several weeks before the spring court election. No one in Dane was getting distracted by or dressed up for a fancy fundraising dinner.

“There’s no way my board members, if I would even suggest it, which I wouldn’t, would ever have gone for that because that would be sucking away our focus from the only thing that matters, which is getting people to the polls,” Sabor says. “Doors. Voters. It’s all that matters. It. Is. All. That. Matters. That is my one job, to win elections and get Democrats elected up and down the ballot.”

But Dane has one more sophisticated turnout machine that is increasingly common in college towns: students themselves. More politically active here than most other college towns, students have been an important voting bloc for years. From Bascom Hill, the historic core of the UW-Madison campus, there is a direct line of sight to the state capitol at the opposite end of State Street. That proximity to power gives their work a sense of immediacy and relevance.

But it’s not just in Madison where students are mobilizing in greater numbers — it’s in most of the counties where there is a university or a UW campus. In the 2022 midterm elections, 49 percent of those aged 18-24 voted in Wisconsin — the highest figure among all 50 states and double the national average.

Wisconsin students of this generation came of age during a period that has felt like partisan wartime defined by mass shootings, climate change, two presidential impeachments, Covid and Jan. 6. Then, last year, Roe vs. Wade was overturned. They understand that every vote counts because they have seen razor-thin margins decide many statewide elections. Trump carried the state in 2016 by less than a percentage point — just 23,000 votes. Four years later, when Biden flipped the state, the margin was even smaller. Recounts and audits followed, underscoring the importance of just a few strategically cast votes.

The spring court election saw the youth vote at its most muscular. One of those students was Maggie Keuler, a 21-year-old senior political science major from eastern Wisconsin. On Election Day, Keuler was out of her apartment by 6:30 a.m. to place 4-by-8-foot campaign signs across the campus before the polls opened at 7 a.m. She ditched her classes to spend the day at a voting information table on Library Mall, the open space that is ideal for wrangling students as they walk to and from classes.

Keuler’s commitment was extreme, but it wasn’t entirely unusual. Emily Treffert, a rising sophomore from Milwaukee County, also says she came to Madison for the politics. She got involved with midterm election organizing efforts during her first semester at college. Then, during her second semester, she joined Project 72, one of a handful of different liberal groups that organized on college campuses across the state.

Project 72’s efforts ranged from the traditional to the outlandish. There was door-knocking, but there were also Thursday night forays to canvass students waiting in lines to get in campus watering holes. Treffert, who at different times wore cow costumes and cowboy hats to get attention, notes that traditional methods of reaching college students haven’t really worked. “We have to create new solutions, new ideas to move the college students because of how impactful their vote is,” she says.

All of that organizing activity led to a huge turnout in the spring elections, especially at the polling locations on college campuses. According to a post-election Milwaukee Journal Sentinel analysis, the highest turnout of the 77 wards in the city of Eau Claire came from the ward that includes a number of UW-Eau Claire dorms.

“The results on campus were astounding,” Keuler says, referring to the vote in Madison. “The turnout was incredible.”

‘Roll Out of Bed, Vote and Go Back to Bed’

The overwhelmingly Democratic nature of the student vote, both in Wisconsin and elsewhere, has left Republicans struggling to respond. Just weeks after the Wisconsin court election, Cleta Mitchell, a veteran GOP election lawyer, gave a presentation at a Republican National Committee donor retreat calling for measures that would limit voting on college campuses.

“What are these college campus locations?” she asked, according to the audio obtained by the Washington Post. “What is this young people effort that they do? They basically put the polling place next to the student dorm so they just have to roll out of bed, vote and go back to bed.”

According to the report, Mitchell focused on campus voting in five states — Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, Virginia and Wisconsin. Each of them features large counties with significant university communities that have flipped from red to blue or are churning out ever bigger Democratic margins.

Among them: the University of Arizona’s Pima County, which has seen Democratic presidential margins grow by nearly 75,000 votes since 2000. In Nevada, Reno’s fast-growing Washoe County — home to the University of Nevada and its 20,000 students — flipped blue in 2008 after decades of backing Republican presidential candidates and hasn’t returned to the GOP fold since. The University of Georgia’s Clarke County has seen its Democratic presidential margins roughly double since 2012. It’s considerably smaller in population than either Pima or Washoe counties, so Biden’s winning margin in 2020 was a mere 22,000 votes. But that’s in a state so closely divided that it was decided by just 11,000.

In the aftermath of the Wisconsin election, former Republican Gov. Scott Walker acknowledged the important role students played in determining the outcome but viewed the problem facing the party in a cultural context.

“Young voters are the issue,” he wrote on Twitter. “It comes from years of radical indoctrination — on campus, in school, with social media, & throughout culture. We have to counter it or conservatives will never win battleground states again.”

Walker, who is president of Young America’s Foundation, a conservative youth organization, has said his group is not seeking to change the ground rules for voting. Rather, he pointed out that conservatives have been “overlooking ways to communicate to young people sooner than a month or two before the election.”

Walker’s criticisms are widely shared on the right, including by Republicans like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has sought to crack down on liberal curriculums and diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives.

In Wisconsin, despite a record-high budget surplus, Republican lawmakers declined to fully fund the University of Wisconsin System’s budget request and voted in June to cut its budget by $32 million — the amount GOP leaders estimated would be spent on DEI programs at the system’s 13 universities.

At the Wisconsin GOP state convention in mid-June, the college mobilization issue remained on the mind of activists. But a resolution calling on lawmakers to require college students to vote absentee in their home communities instead of on campus was tabled, in part because of the opposition of Republican county chairs in Milwaukee and Dane County.

“Why on Earth would we send a message to the students that we don’t want them to vote our way?” Milwaukee County GOP Chair Hilario Deleon told his fellow party activists. “Do not give the Democrats ammunition, give them competition.”

Spread the word