Amid the endless interesting details of the climate and energy fight, I find myself sometimes losing track of the basic outlines of our the dilemma. So let’s try to oversimplify it for a moment, just to make sure we’re at a place we can work from. The key, as always, is the sun.

Right now, thanks to our recklessness, the sun is overheating our planet. And by right now, I don’t mean in this century. I mean, in this month. The global temperature readings for September should have been the top story on every newscast in the world, because they were bonkers. June, July, and August were historically hot—we saw the hottest days recorded on the planet in 125,000 years. September wasn’t quite as hot, of course, because it’s fall. But in relative terms September was even more outrageous. It was, the scientists tell us, the most anomalous month we’ve ever seen, with temperatures so far beyond historical norms that the charts don’t even seem to make sense.

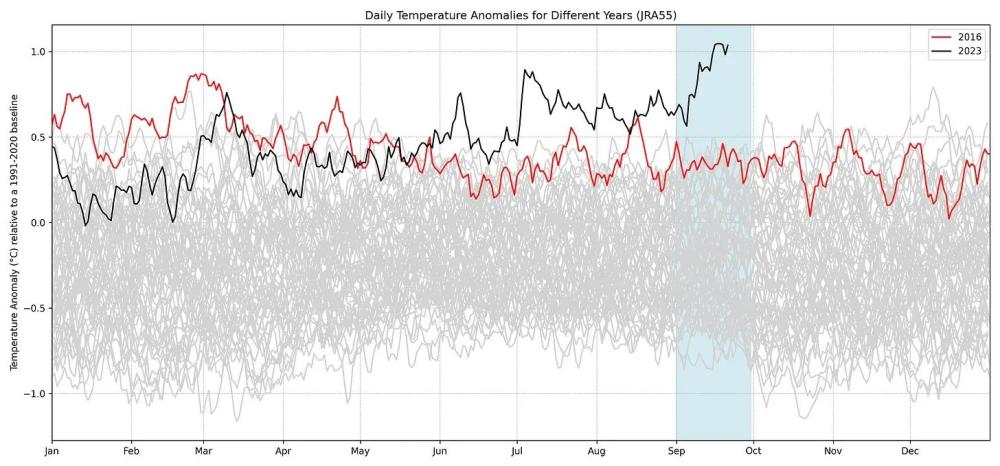

For instance, here’s the chart that the estimable Zeke Hausfather prepared using data from the Japanese Meterological Agency.

All those gray lines are the temperature anomalies for many years back; the black line at the top is this year, and the blue area is September. As the Washington Post reported, “the planet’s average temperature shattered the previous September record by more than half a degree Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit), which is the largest monthly margin ever observed.”

We have, in effect, turned September into July. That’s not hyperbole, that’s just data. And in so doing, September smashed through the 1.5 degree Celsius warming mark that the world set as a target in Paris just eight years ago. We’ve been talking about it ever since, and now we’re there.

And there’s no huge mystery about why. Yes, we’re in an El Niño, though it’s only now kicking in. Yes, reduced air pollution from ships and Asian cities means less sun reflected. But, basically, the gases we’ve poured into the atmosphere are turning the sun from our greatest friend into our most daunting problem.

And at the exact same time, the sun is our greatest hope for getting us out of our predicament. Again, there are lots of other things we could talk about: whether we’ll eventually have small nuclear reactors, or deep geothermal power, or a dozen other possible wonders. But right now, in the same months that the planet is overheating, our cheap quick ways out of trouble rely on that same ball of burning gas orbiting 93 million miles above us. They are solar panels that catch the sun’s rays directly, and wind turbines that take advantage of the fact that the sun differentially heats the earth, creating the breezes that make them turn.

So here’s what good news I’ve got. At the same moment that the planet is starting to broil, the solar market is starting to cook. I was walking the streets of Manhattan during Climate Week when Danny Kennedy—legendary solar entrepreneur—pulled up on his City Bike. “We’re at a gigawatt a day,” he said with a grin.

“What?” I said.

“The planet is now adding a gigawatt a day of solar power. A nuclear plant’s worth every day of solar power,” he said. And what do you know, he was as usual correct. About half the total is being added in China, apparently even amidst their economic trials (and far outdistancing the increase in their fossil fuel plants). The U.S. is second, followed by Brazil and India.

Is this enough? Nowhere near.

Is it stable? No—when I talked yesterday with Mary Powell, the CEO of Sunrun, she said rising interest rates and languishing government help may mean that American installations actually fall this year.

But is it remarkable? Yes. Think of the work that traditionally goes into building a new power plant: the years of work and planning and pouring concrete. We’re building the equivalent of one of those every day now, and instead of burning coal or gas they’re letting the sun handle the combustion.

The numbers are going up so fast that they really can’t be denied. The International Energy Agency—the club of big oil users that Henry Kissinger cobbled together in the 1970s—puts out an annual report, and for decades it was notorious for underestimating how fast renewable energy would grow. But no longer. As Kingsmill Bond and Sam Butler-Sloss point out in their highly useful gloss on the new report

The report is a significant change in tone since the 2021 net zero roadmap. That report was all about ‘should’ while this report is all about ‘will’. As the result of the continued rapid growth in renewable deployment, the IEA has moved from a theoretical exercise in 2021 to embracing the prospect of a net zero future with enthusiasm.

Even without accounting for, you know, the destruction of the earth, the rapid buildout of renewables is cheaper than business as usual—it takes a little more capex (capital expenditure) to build all those solar panels than to keep replacing fossil fuel infrastructure, but the opex is far lower because…the sun delivers the power for free, while Saudi Arabia and Exxon charge.

We should go much faster—and we could. Despite the ongoing efforts of the fossil fuel industry gin up NIMBY opposition, a new survey finds that Americans are willing to live next to solar and wind farms.

Three-quarters of all Americans say they would be comfortable living near solar farms while nearly 7 in 10 report feeling the same about wind turbines. And these attitudes appear to remain largely consistent regardless of where people live. According to the poll, 69 percent of residents in rural and suburban areas say they would be comfortable if wind turbines were constructed in their area, as do 66 percent of urban residents.

General comfort with green energy infrastructure crosses party lines, with 66 percent of Republicans saying they are comfortable with a field of solar panels being built in their community and 59 percent comfortable with wind turbines. Among Democrats, 87 percent are comfortable with solar farms and 79 percent with wind farms.

But the race is on. And that’s what it is, a flat-out race to build as much renewable energy—and to keep in the ground as much fossil energy—as we possibly can, in the hope that eventually that rising technological curve will bend that rising temperature curve. It’s amazing that they’ve both gone somewhat vertical at precisely the same moment, but that’s the story of our time on earth.

The sun keeps pumping out more or less the same amount of energy day in and day out. It’s what we do down here on earth that will decide whether it cooks us or saves us.

In other energy and climate news:

+Pope Francis has once again shown he may be the world’s most useful environmentalist: his new letter on climate change, though much shorter than the monumental encylical Laudato Si of the last decade, is wonderfully specific and pointed. He begins with an efficient and necessary rebuttal of the denier arguments that the fossil fuel industry has worked so hard to spread:

In recent years, some have chosen to deride these facts. They bring up allegedly solid scientific data, like the fact that the planet has always had, and will have, periods of cooling and warming. They forget to mention another relevant datum: that what we are presently experiencing is an unusual acceleration of warming, at such a speed that it will take only one generation – not centuries or millennia – in order to verify it. The rise in the sea level and the melting of glaciers can be easily perceived by an individual in his or her lifetime, and probably in a few years many populations will have to move their homes because of these facts.

He calls on humans to rethink their ideas on power; this is the deepest and most philosophical section of the paper, and worth careful reading. But he also has very practical and pointed things to say about how government and industry should be moving in the fall of 2023

The United Arab Emirates will host the next Conference of the Parties (COP28). It is a country of the Persian Gulf known as a great exporter of fossil fuels, although it has made significant investments in renewable energy sources. Meanwhile, gas and oil companies are planning new projects there, with the aim of further increasing their production. To say that there is nothing to hope for would be suicidal, for it would mean exposing all humanity, especially the poorest, to the worst impacts of climate change.

If we are confident in the capacity of human beings to transcend their petty interests and to think in bigger terms, we can keep hoping that COP28 will allow for a decisive acceleration of energy transition, with effective commitments subject to ongoing monitoring. This Conference can represent a change of direction, showing that everything done since 1992 was in fact serious and worth the effort, or else it will be a great disappointment and jeopardize whatever good has been achieved thus far.

He ends with a few pointed words for Americans (whose bishops have too often been in league with the climate-denying GOP)

If we consider that emissions per individual in the United States are about two times greater than those of individuals living in China, and about seven times greater than the average of the poorest countries, we can state that a broad change in the irresponsible lifestyle connected with the Western model would have a significant long-term impact. As a result, along with indispensable political decisions, we would be making progress along the way to genuine care for one another.

+Dengue fever—the quintessential disease of global warming—is now spreading fast in southern Europe and threatening to become a fact of life in the southern U.S. as the mosquito that carries it relaxes into the warm, wet world we’ve built for it. More tragically, dengue—long a scourge in Asia and Latin America—is now spreading into Africa. Having had dengue in Bangladesh—where record numbers of deaths are being reported this year—I can testify to the sadness of this story: it is a terrible disease.

+Rebecca Leber reports in Vox on how the fossil fuel industry is attempting to derail the drive towards electric school buses, hoping they can convince school boards to buy propane models instead.

To make school buses better for the climate and for kids’ health, the federal government and states are pushing to electrify their fleets. Virtually all of the nation’s 500,000 school buses are expected to turn over in the next 15 to 20 years, but EV buses are still in their infancy: There are nearly 6,000 electric buses on the road today or planned soon, making up just 1 percent of the auto total sector, according to World Resources Institute, a nonprofit research organization. With new incentives, federal regulations, and zero-emissions state targets, that portion of EV school buses is projected to grow 20 percent. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law alone devotes $5 billion in the next five years to cleaning up school bus pollution.

But even with federal subsidies, this shift to EV buses will be expensive, especially for public school districts, and the propane industry sees an opportunity to seize a share of the auto sector. Its representatives are working hard to convince public officials to switch to propane-fueled school buses, which they claim are “near-zero emissions” vehicles that are better for kids and the climate.

Except — that’s not true. Propane is still a polluting fuel: While it is refined differently than diesel and natural gas and combusted in uniquely styled engines, it still has a measurable impact on air quality and the climate. If PERC’s deceptive marketing to children, parents, and school administrators is successful, the propane industry threatens to lock in fossil fuels and their polluting emissions for another generation of schoolchildren.

+Australian police are demanding that television journalists turn over raw footage so that they can identify peaceful activists

Police have applied through the courts for all footage shot in the preparation of a program about climate protesters. The program, titled Escalation and due to air on Monday, investigates the battle between climate activists, the government and energy companies over the massive gas project on the Burrup Peninsula in the Pilbara.

+Scientists are rallying to oppose plans to dump carbon dioxide from various capture schemes in national forests

In June the Forest Service announced it would issue a rule as early as this month giving “perpetual right of use” for carbon waste injection in national forests. Today’s petition, signed by people and groups across the country, says a leak at a carbon waste site could suffocate or even kill people and wildlife.

“This proposal is nothing short of ludicrous,” said Laura Haight, U.S. policy director for the Partnership for Policy Integrity. “Our national forests are already home to the most viable carbon capture and storage technology on Earth — they’re called trees.”

Carbon dioxide waste injection would require building massive amounts of infrastructure, including pipelines, injection wells and well pads. Road building, construction and logging would cause additional harm to forest ecosystems and recreation.

“Turning our national forests into industrial dumping grounds is outrageous and completely wrongheaded,” said Victoria Bogdan Tejeda, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute. “There’s no place in our national forests for carbon capture scams that only benefit polluting industries. The administration should scrap this rule and enact one that protects mature and old-growth forests and trees.”

+A useful new paper works to refute “dangerous narratives” about climate and migration

“Climate refugee” is not a legal category. Formal pathways for climate migration are severely underdeveloped. Unlike for refugees, there is no specialised body of law regulating the treatment of migrants who are forced to flee due to climate-related impacts, nor are there dedicated international institutions.

Climate communicators may want to use the term “climate refugee” as a way to push for legal recognition within the 1951 Refugee Convention or, more commonly, just as a shorthand term that captures people’s attention/understanding. But refugee advocates are, among other things, nervous that renegotiating that treaty will almost definitely result in weaker protections for everyone.

While the term may resonate for organisers and for some people who indeed are forced to move in the face of climate disasters, care must be used to distinguish the concept of a “climate refugee” from the legal protections afforded to other refugees and asylum seekers globally. Focusing on the category of “refugee” may also ignore the complexity of factors that lead to a person's decision to move from their home.

+ The always-thoughtful George Monbiot offers an important new essay on the dangers of romanticizing ‘peasant’ life—as he reminds us, we need a food system that can deliver enough affordable calories for a largely urbanized planet without overwhelming ecosystems.

We benefit above all from the marvel of the past 50 years of falling hunger during a time of rising population, a marvel we in the rich world scarcely acknowledge, so comfortable has it made us. This remarkable phenomenon was widely considered, just 60 or 70 years ago, simply impossible.

There are three things upon which I think we can all agree. First, that this marvel came at a great environmental cost. It was delivered through hungry and thirsty new crop varieties, reliant for their survival on lashings of agrochemicals, unsustainable water use and practices that can accelerate soil degradation. Second, that it also involved severe social and political dislocations, including land-grabbing, enclosures and rising corporate power and concentration. Third, that it might now be running out of road: the prevalence of global undernourishment rose from 613 million (median estimate) in 2019 to 735 million in 2022.

+The ongoing fight to block the expansion of a private jetport near Boston got a boost last week when the Globe’s David Abel reported that it was largely supporting billionaires headed to resorts

The report, released Monday, analyzed 18 months of flight data from Hanscom starting in January 2022, and found that some 31,000 flights by 2,915 private jets produced an estimated 107,000 tons of carbon pollution. About half the flights were probably for recreational or luxury purposes, based on their resort destinations and weekend flight dates, the authors said.

Executives at Suffolk Construction, owned by John Fish, have used the Boston-based company’s private jet nearly 250 times since last year to fly from Hanscom Field to destinations such as Aruba and Aspen, Barcelona and Rome, Martha’s Vineyard and Napa Valley, according to a new report.

Suffolk’s 19-passenger Gulfstream Aerospace GV-SP 550 flew every two or so days, its Rolls-Royce Pearl engines pumping out an estimated 2,329 tons of carbon emissions, according to the report, which catalogued the climate pollution from flights to and from New England’s largest noncommercial airport.

The Suffolk jet burned more than any other based at Hanscom, and about 230 times more than the average Massachusetts resident produces in a year, the report found.

+A new report from the US Treasury warns that climate change could impose “substantial financial costs” on American consumers, which seems like a no-brainer. But remember, until recently many prominent economists had been arguing that a growing economy would outpace any damage. Now reality is starting to hit home

Flooding and wildfires can damage businesses, forcing employers to furlough or lay off staff, the Treasury Department found. This could lead workers to lose their pay for a period, and potentially their workplace benefits, including health insurance or retirement plan support.

Recurring hazards such as wildfires or heat waves could reduce the available jobs in certain sectors, leading to long periods of unemployment for people. Workers in the fields of agriculture, construction, manufacturing and tourism may be especially hard hit.

Meanwhile, “outdoor workers,” as the report describes those who spend more than two-thirds of their workday outside, comprise about a fifth of the civilian workforce and are among the most likely to see their hours and pay disrupted.

+Meanwhile, it’s been taken as gospel that building EVs will require fewer workers. But Emily Pontcorvo reports that may not be the case. According to one report,

EV manufacturing required more hours. The conventional powertrains took 4 to 11 worker hours, while the EV powertrains took 15 to 24. “A lot of the confusion sits around, what parts are you counting in this evaluation?” Cotterman told me. “We’re saying that if you were to produce every single component in an EV in the U.S., that the total sum of those powertrain components will be higher than the equivalent ICE components.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

October 14, 2023

Spread the word