Released theatrically in 2019; the film is now streaming of Netflix.

The astonishing “Last Black Man in San Francisco” is about having little in a grab-what-you-can world. It’s the haunting, elegiac story of Jimmie Fails — playing a version of himself — a young man trying to hold onto a sense of home in San Francisco. His parents are missing in action and someone else lives in the family’s old house. Given to dreamy, faraway looks, Jimmie seems not quite there, either. But he remains tethered to the city, somehow exalted by it. And when he slaloms down its hills on his skateboard, he doesn’t descend — he soars.

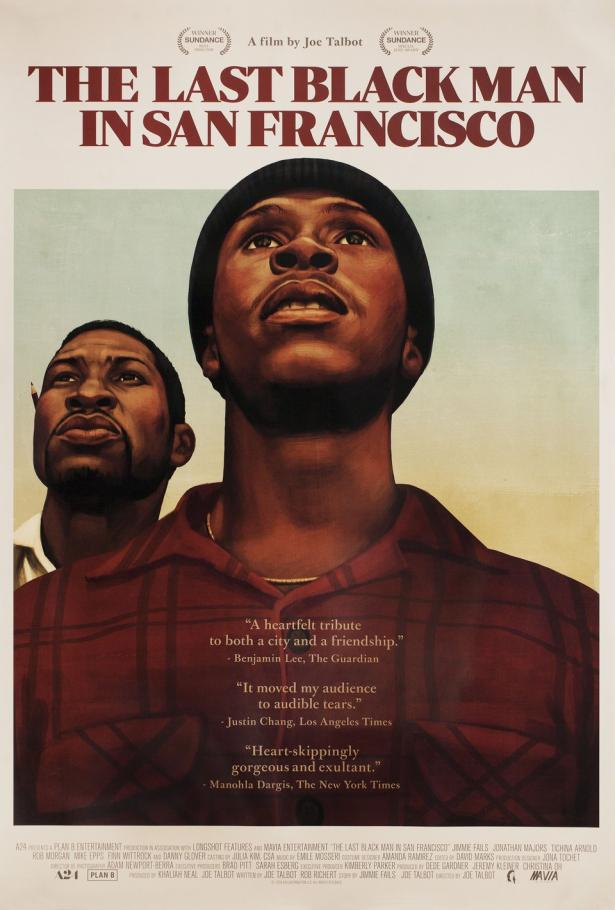

The movie was directed by Joe Talbot, a longtime friend of Fails’s, and together they came up with a story grounded in life. Like Jimmie’s family, Fails’s also lost its home, and he and his father — played by Rob Morgan in a brief, piercing turn — bedded down in their car. It’s a plaintive American narrative that here becomes an expressionistic odyssey, both rapturous and melancholic. In moments it feels as if Jimmie and his faithful artistic friend, Montgomery (Jonathan Majors, a mournful heartbreaker), are dreaming the movie into existence, pouring its surrealistic jolts and hallucinatory beauty out of their heads and straight into yours.

The story drifts in, as if taking its cue from the fog. Jimmie works at a nursing home, but with no home to call his own, he flops at Mont’s grandfather’s house, a proud and cramped relic facing a polluted bay. There is an ease to the men’s intimacy, a feeling of refuge that wraps around them whether they’re talking or watching old films with Mont’s blind grandfather (Danny Glover, a monumental presence). Early on, the three watch the 1949 noir “D.O.A.,” raptly attentive as Edmond O’Brien reports a murder (his own!) in San Francisco, Mont narrating each beat for his granddad.

The tiny audience basking in the flickering light makes for a charmingly eccentric tableau. In another movie, it might read as decorative filler, the kind filmmakers use to mortar together story-advancing scenes. Except that everything counts: the specter of death, Mont’s narration, Jimmie’s perch on the floor. Each detail adds meaning to a story that builds associatively and obliquely, and often through nods rather than shouts. Jimmie is safely huddled in this room, but loss — of his parents, home and city — pervades his life, which means that (just like Edmond O’Brien’s) his future might be lost too.

Much of the story and its tension involve Jimmie’s stubborn claim on his family’s former house, a majestic Victorian in the Fillmore district. An older white man and woman live there now, which doesn’t stop Jimmie from rebuking them about the garden or propping up a ladder to paint a windowsill. When they leave for good, Jimmie surreptitiously moves in, filling the wood-paneled rooms with the furnishings that his father didn’t lose during the family’s grimmer times. Mont moves in too and it’s there that he will at last turn his ideas — the scribbles and delicate drawings that fill his red notebook — into a climatic, reflexive theatrical performance.

This more or less explains what happens, but it’s the how that matters in “Last Black Man.” This is, remarkably, the first feature directed by Talbot, who shares screenwriting credit with Rob Richert. The story has a clear through line in Jimmie’s odyssey back home and beyond. When he’s not staring into the distance (an untrained performer, Fails has a face for contemplation), Jimmie is on the move, storming San Francisco on his skateboard or rowing off in a fantasy. Mostly, the movie has a cascade of images and ideas, reference points and glimpses of everyday beauty that flow and swirl and, over time, gather tremendous force.

The history of black San Francisco is folded in here as well, directly and otherwise. The movie opens opposite the grandfather’s house with a girl looking up at a man in a hazmat suit. She soon skips out of the story, and while there are other references to pollution, you need to dig on your own to know more about the neighborhood, Bayview-Hunters Point, which sits on a peninsula in the San Francisco Bay. For decades, the Navy maintained a shipyard there on which it studied radiation and decontaminated ships exposed to atomic testing. The shipyard employed thousands of African-Americans, and when it closed area unemployment spiked.

“Last Black Man” belongs to a handful of recent Bay Area movies about the African-American experience that includes “Blindspotting” and “Sorry to Bother You,” both set in Oakland. In each, black characters confront (among other things) gentrification, a polite word for what, in effect, is a form of white colonization. Taken together, these movies pick up a thread in Barry Jenkins’s wistful 2008 romance “Medicine for Melancholy,” which tracks a young black man and woman through San Francisco. The man hates the city, but also loves it. The hills, the fog — it’s beautiful — and “you shouldn’t have to be upper middle class to be part of that.”

In “The Last Black Man in San Francisco,” the desire for home is at once existential and literal, a matter of self and safety, being and belonging. This is of course part of the story of being black in the United States, which perhaps makes the movie sound like a dirge when it’s more of a reverie. Or, rather, it’s both at once and sometimes one and then the other. Much depends on Jimmie, who waxes and wanes, sometimes rises and then falls in a city that — with this ravishing movie — he insistently stakes a claim on, one indelible image at a time.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

Rated R. Running time: 2 hours.

Spread the word