Carroll has served as the historian and archivist for the Brigade and has written the magisterial Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War (Stanford, 1994). Over the years, he has interviewed many of these brigadistas and has included poems about the war in his nine earlier poetry collections. Now after five years of research he has given us "a work of poetry non-fiction” paying tribute to them in “poetry takes the task of understanding and empathy one step further.” Carroll’s assessment is spot on. The poems are historical and personal at once, and, I suspect, a catharsis for both poet and those who honor these heroes. Doing so, he has “put the Lincoln Brigade back on the map” and helped us to see how these horrific events in Spain foreshadow or at least parallel those in America such as the McCarthy witch hunts, civil rights tragedies, Watergate, the Iran-Contra plot, the plight of immigrants, and, of course, the assaults on Ukraine and the Israeli-Hamas War today. Carroll’s poems about the Spanish Civil War thus point to the persistence of fascist-like atrocities that continued far beyond the 1930s.

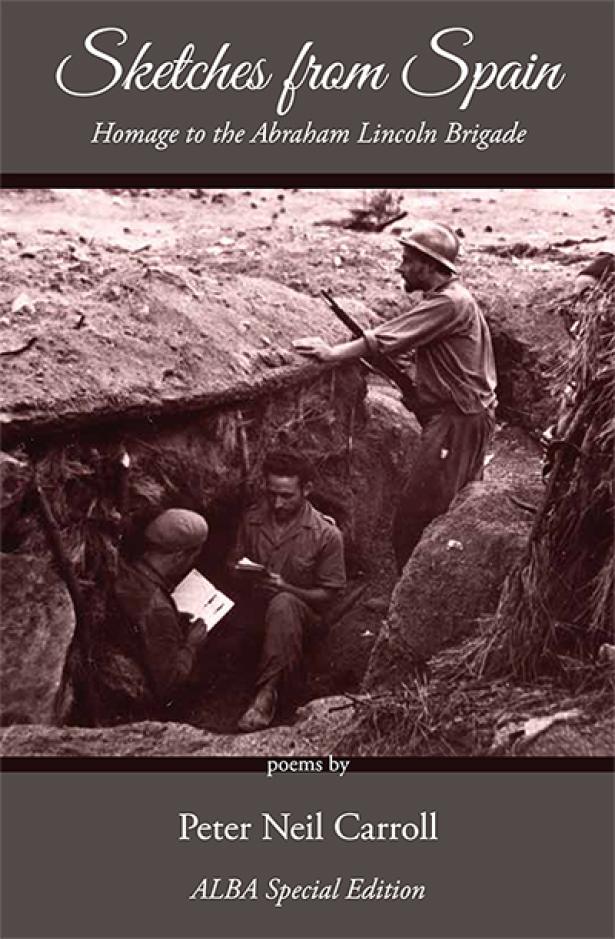

Sketches from Spain: Homage to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade

By Peter Neil Carroll

Main Street Rag, ALBA Special Edition; 110 pages

January 24, 2024

Paperback: $20.00

ISBN: 978-1-59948-981-0

Each of Carroll's 80 plus riveting poems bears the name and dates of one of the Brigade for a title, and most of the poems include italicized lines with the words of these individuals gathered from letters and other documents. Carroll's words mix with those of the Brigade, poetry and non-fiction. Some poems contain only italicized lines. Individually or collectively, the poems can be classified as mini-biographies, encomia, dramatic monologues, lamentations, eulogies, jeremiads, tombstones, or even love letters e.g., love of freedom, love of the oppressed. Each poem is a haunted memory of these individual heroes in their embodied voices heard in Carroll’s poetic lines and their own words. The brigadistas represented a cross-section of occupations and nationalities; doctors and nurses, artists and writers, barbers and florists, coal miners and taxi drivers, students and seamen; some as young as “an 18-year-old shouldering a Russian riffle” or as experienced as a 40-year-old ambulance driver. Their ethnic backgrounds were equally diverse—British, Finns, French, Irish, Italian, Polish, even Japanese. But they were all activists determined to defeat Franco’s (and Hitler's and Mussolini's) fascist dictatorship. “There is no sacrifice we can refuse,” declared one of the Brigade.

Regardless of their backgrounds, they all voice the horrors of this war. Boleslaw “Slippery” Silvon insisted, “I almost forgot to tell you about our bombing we got the other day. . .they flew low as hell strafing their machine guns, people panic stricken, running for shelter. . . .” Esther Silverstein (Blanc) recalled “the constant threat, how fascist bombers targeted rooftops and tents marked by hospital insignia.” Doesn't this sound like Ukraine or Gaza, yesterday, today, or, fearfully, tomorrow. The poems are filled with loss. In a poem about Hank Rubin, Carroll observes: “Everyone who came with him to Spain, left behind a limb or a life.” In Alvah Bessie's poem, Carroll tells us this volunteer “saw horror, terrified men running for life.” Lincoln volunteer Dr. Leo Eloesser described the Spanish Civil War as “an epidemic of injuries.” Eight hundred of the Brigade died trying to defeat fascism and preserve the Spanish Republic. In a passage from Hemingway’s On the American Dead in Spain, serving as an epigraph for Carroll’s collection, we hear: “No man ever entered earth more honorably. . . already have achieved immortality.” But despite or in spite of these losses, the Brigade displayed fierce, unwavering loyalty. The poem on Oscar Hunter begins: “He was asked at age 72/ if he would do it all over-- replied, Yeah, every bit.”

Racial discrimination is another topic that runs through these poems, a sign of those times and, sadly, ours, too. References to Jim Crow, lynching, and other racial horrors surface in poems about the Black men and woman who served in the Brigade. A Black Mississippi youth, Eluard Luchell McDaniels was arrested once along with the white woman driving him. When white members of the Brigade expressed jealousy over the promotion of a Black officer, Oliver Law, Carroll reminds us that this was an anti-fascist army that fought as a unit. Of Salaria Kea, Carroll points out: “She stood out, the one African American/woman in the Spanish Civil War, a nurse who/ spoke her mind, fought racism, and saved lives,” virtues that characterized the Lincoln Brigade. But Carroll also records the prejudice she faced at home. “When the Ohio River flooded, she offered to help/ the Red Cross. They replied the color/of her skin was more trouble than she was worth.”

Equally pernicious attacks were launched against the politics of the men and women of the Brigade shortly after and much later, accusing them of being Communists. A Black member, James Bernard “Bunny” Rucker suffered on both accounts. “The Jim Crow army had other indignities [for him] but as/ a Spanish Civil War vet, Rucker confronted (like white vets)/ discrimination as a suspected Communist. A hospital commissar “for the wounded and the sick/ Oscar Hunter years later faced “the FBI in the Red Scare/ of the fifties, and lived long enough/ to protest the war in Vietnam.” One of Carroll’s most powerful poems (among many) turned to Jack Lucid (1915-1977), “the old Communist” who served drinks behind the bar. As one of his customers, Carroll declared:

He has stories./ Oral history we call it: I want his past, he hopes/ I’ll give him a future. He pours, I drink We begin. . . When we walk through the zoo admiring caged monkeys, talks about a Nuremberg Tribunal for Richard Nixon. . . .

This fusion of time (past into future; present into past) is a hallmark of Carroll’s intense desire to show history repeating itself. Many of the poems like Lucid’s are warnings about what happens if and when fascism comes to America. We learn, for example, that “While sleuthed by the FBI, persuades an agent/ to give him free rides; he can live without his car./ At his job in a mayonnaise factory, he declines/ promotions so immigrant workers get better pay./ One night he warns me his comrades are dying fast./ He says I'll be seeing you soon—as a ghost./ We scatter his ashes, as he wished, with the fish/ outside the Golden Gate where no one could find him.” A gut-wrenching tribute to this volunteer soldier who brought the values of the Brigade home with him even as he defied America four decades later. In a sense, Lucid’s biography—and his quotations—are the bedrock of belief that underlies Carroll’s carefully crafted and compelling poems.

Sketches concludes with “Paul Robeson's Legacy,” a fiery poem on how this controversial actor and singer changed the words of a song he had performed to emphasize the overwhelming influence the Spanish Civil War had and how “La lucha continua: the struggle continues.” Transformed in Robeson’s lines, civil rights leaders such as Dr. King or Rosa Parks become “Spanish Civil War veterans” who “re-entered font lines in Mississippi, the south side Chicago, Louisville, Harlem, Selma, Newark, Detroit, Seattle, Sacramento, San Francisco.” The Spanish Civil War and those who fought in it on the side of the Republic brought their bravery and convictions home with them and it became one of the most influential events in American history. As Carroll declares in one poem, “The Spanish Civil War never ended.” His meticulously researched, jaw dropping poems will make sure it never does. They are necessary reading to understand why.

[Philip C. Kolin is the Distinguished Professor of English Emeritus and Editor Emeritus of the Southern Quarterly at the University of Southern Mississippi. He has published 15 collections of poems, the most recent being White Terror, Black Trauma: Resistance Poems about Black History (Chicago: Third World Press, 2023).]

Spread the word