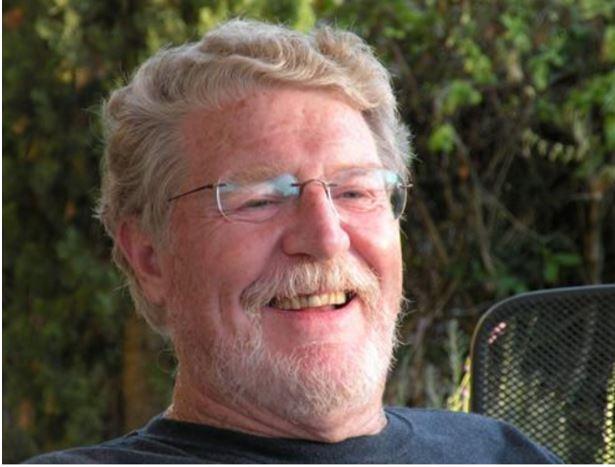

One of the warmest lights from San Francisco’s most storied left family, Conn Malachi Hallinan, died June 19, at his home in Berkeley after a long fight with cancer. He was 81.

A son of legendary San Franciscans left luminaries, Vincent and Vivian Hallinan, Conn, popularly known to his multitude of friends as “Ringo,” carved his own reputation as an activist, journalist, prolific columnist on world affairs, educator, and in later life a novelist.

After earning a PhD in Anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, Conn, or Ringo as we’ll call him here, commenced a brilliant 40-year journalism career, including churning out hundreds of columns over five decades for Foreign Policy in Focus, which were often reprinted in multiple main-stream as well as left leaning publications, and internationally in Europe, India, and Australia. He spent 23 years overseeing the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) journalism program where he mentored several generations of journalism students and won three UCSC awards for Distinguished Teaching, Innovations in Teaching, and Excellence in Teaching, and acted as Provost of Kresge College at UCSC from 2001–2004.

Conn’s political moorings were doubtless a Hallinan inheritance. A grandfather, Patrick, was reputedly a member of The Invincibles, an Irish revolutionary organization. After fleeing to San Francisco, he became a leader of a 1901waterfront strike. Patrick’s son, Vincent, who grew up poor in a house demolished by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, was a successful amateur boxer and crusading defense attorney, taking on “unpopular” causes and prominent defendants.

The most notable was working class giant Harry Bridges, leader of the 1934 San Francisco general strike and president of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union, whom he defended against the U.S. government’s push to deport Bridges for his left politics. Vincent also ran for President in 1952 as the candidate of the Progressive Party.

Matriarch Vivian Moore Hallinan, who chronicled family lore in My Wild Irish Rogues, was also a social and political activist. As the Los Angeles Times later noted, she “marched against the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia, went to jail for supporting civil rights, (and) was targeted by the FBI and was gassed during an anti-Pinochet rally in Chile.” Through canny investments in San Francisco apartment houses, Vivian provided critical financial solidarity support to groups resisting President Reagan’s interventionist proxy wars in Central America, especially Nicaragua.

After Vivian and Vincent moved from San Francisco to Marin County, she witnessed the sharp contrast between low-income Marin City and posh Ross, where they now lived. Vivian would tell artist Pele de Lappe, later Ringo’s colleague at the People’s World newspaper, “it seemed to me that the leaders of our country, instead of spending their energies cursing those with different systems and shaking their fists at them, would do better to reform the social and political injustices at home.”

They raised six sons, all of whom would carry on their political upbringing. Regularly confronted by neighbors where, Vivian observed, “even a reactionary Democrat was considered a ‘Red’,” they fought back. Vincent hired former welterweight champion Tony “Frisco” Curro to teach them boxing skills, even, son Matthew relates, building a gym with a boxing ring after oldest son Patrick was attacked by soldiers who broke his arm during the Korean war at the height of the Red scare.

The Hallinan boys gained not only pugilist training but also fisticuffs nicknames, in age order: Patrick (Butch), who became a high profile criminal defense attorney; Terence (Kayo), a San Francisco Supervisor and District Attorney (ultimately losing to Kamala Harris in her inaugural political campaign); Michael (Tuffy); Matthew (Dynamite), a lifelong political activist who ultimately ran the family business; Conn (Ringo, after briefly being called Flash), and Danny (Dangerous, but a nickname he was never called). Only Matthew and Danny survive.

Their Ross home was a political magnet for other left and progressive icons. Danny remembers legendary Black scholar/historian W.E.B. DuBois living in their Ross home for a month in 1959. Vivian was close to the DuBois family, especially his wife, Shirley Graham, often vacationing with them in Barbados. Years later, Vincent and Vivian hauled all six sons to Washington for the March for Jobs and Freedom led by Dr. Martin Luther King in August 1963, after which Ringo and Danny accompanied Vivian to DuBois’ funeral in Accra, Ghana. where he had lived his last few years in exile.

Political activism was never far away. At 17, while a senior at Redwood High School in Larkspur, Ringo inspired 200 fellow seniors to stage a two-hour car procession around Marin County to protest the execution at nearby San Quentin prison of Caryl Chessman in May 1960. Ringo climbed on top of his car and urged fellow seniors to act.

After graduation, Ringo, and Terence spent 10 months in London. In April 1961, then joined by brother Danny, the three Hallinans took part in one of the famous Aldermaston ban the bomb Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament actions. “We marched around the nuclear plant at Aldermaston, and then with thousands for 52-miles over 4-days to London. It was very comradely, thousands of people marching and singing peace songs,” Danny recalls.

That fall, Ringo enrolled at San Francisco State University, playing football for the Gators as an offensive lineman, building on his love of the sport he had played in high school on a team that won the Northern California championship. With most of his brothers, he was soon engaged in protests and civil disobedience in a burgeoning San Francisco and Bay Area left and student uprising, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. The Berkeley campus, Ringo later noted “was already a center of political activity. Berkeley’s progressive student organization, SLATE, helped chase the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) out of San Francisco in 1960, and Cal students had joined demonstrations challenging the racist hiring practices of San Francisco’s hotels and car agencies.”

“I first met Ringo around 1963 as the DuBois Clubs were beginning to grow,” relates his lifelong friend, writer and organizer Michael Myerson (now living in Brooklyn). “We — the DuBois Clubs and the Ad Hoc Committee Against Discrimination — were conducting non-violent action campaigns against large employers who would not hire (or place in anything but menial positions) Black workers. We started with the Mel’s Drive-In restaurant chain in Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco; then moved on to the San Francisco hotel industry and the automobile sales industry.” Ringo led the DuBois San Francisco State chapter. Most of his family was also soon involved.

“We were all watching what was happening in the South, and wondering what can we do,” recalls Matthew. “We got the word from a Black employee at Mel’s Drive-In that Black employees were only allowed to wait tables and were not hired in almost all of them. We decided let’s integrate Mel’s Drive In,” using the sit-in campaigns in the South as a model.

By March 1964, Vivian and the five older sons had lots of company as mammoth crowds challenged the hiring bans, at the swanky Sheraton-Palace Hotel and a Cadillac dealership on the city’s Van Ness Avenue auto row, shaming San Francisco’s liberal image. “The Cadillac agency sold lots of Cadillacs to black people, but there were no black car salesmen,” Terence told the San Francisco Chronicle 50 years later. “Thousands of us were arrested, including most of the Hallinan brothers. After one of the arrests, I shared a jail cell with Tuffy,” notes Myerson. “Did it make a difference? Sure, it did. It made a huge difference,” Terence told the Chronicle, noting he was arrested with three of his brothers, including Ringo, and Vivian too. He got 60 days in jail, Vivian got 30 days. “This,” she said dryly at the time, said Terence, “is not a Caribbean holiday.”

Future California Assembly member/Los Angeles Council member Jackie Goldberg recalled in the film “Berkeley in the Sixties” how the demonstrations, especially mass Sheraton arrests, produced the first major civil rights victory of its kind in the North between the hotel industry and Ad Hoc Committee “to end discrimination and hire minority individuals at all levels of employment, including management. It really pumped us all up to think, my god, we really could have an effect on history.” Other San Francisco businesses secretly decided to end their segregation policies too, Matthew notes.

The involvement of Berkeley students produced a backlash by the administration, banning student tables and other political activism. It led directly to the eruption of Berkeley’s historic Free Speech Movement in the fall of 1964, also inspired by the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964 where several Berkeley students who led the Free Speech Movement had just returned. As the battle raged in late November, Ringo, who had transferred to Berkeley that fall, was among 800 fellow arrestees at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Hall in December 1964, along with brothers, Matthew Patrick, and prominent free speech leaders Mario Savio, Bettina Aptheker, Jackie Goldberg, and Jack Weinberg.

By 1965, the East Bay was a hotbed of protests against the U.S. war in Vietnam. “When I first met him, he was just becoming chairman of the Berkeley DuBois Club,” recalls Ringo’s longtime friend Jack Radey. Ringo was also a leader of the Vietnam Day Committee, which in the Spring of 1965 led anti-war teach-ins on campus. That fall the fight escalated. The Vietnam Day Committee organized actions to try to stop “troop trains” carrying soldiers off to the war and led marches to the Oakland Induction Center in West Oakland seeking to discourage inductees.

After a night march in mid-October 1965 was turned back due to heavy police presence and the threat of police violence, thousands of marchers joined a mass mobilization the next day. Ringo, Radey, and Jack Kurzweil, another longtime friend, were part of march security. When they reached the Oakland city line, they were confronted by a massive row of Oakland police standing shoulder to shoulder, Kurzweil recalls. Beyond them stood a group of Hells Angels, an often-violent motorcycle gang. The Oakland police suddenly opened their ranks to allow the Hells Angels to rush through to attack the student marchers.

Radey says he and Ringo, a security captain, were at the front, with most of the marchers well behind. He says Ringo directed him to cover an area that “I only realized later he was putting me out of harm’s way.” The Hells Angels attacked, as shown in the film Berkeley in the ’60s, following their leader, Sonny Barger. “Ringo, scowling, wearing a wooden-toggled wool coat, crew cut and freckled with dark rimmed glasses, looking very collegiate. Sonny must have thought so too. Bad mistake. Ringo (well trained) dropped him like a bad habit.”

Some more sedate years followed. Ringo worked on his graduate studies, parented the first of his four sons, and helped, as chapter vice president, form the first UC Berkeley union of graduate teaching assistants, a chapter of the American Federation of Teachers. Though it did not have official UC recognition, “it won a grievance procedure, to everyone’s surprise,” and engaged in other actions, Radey remembers.

Ringo met Carl Bloice in 1961 and they were friends until Carl’s death in 2014. Carl had been one of the DuBois Clubs founders, a veteran of the Vietnam protests, and one of the first Northern reporters to go into the deep South to chronicle the Civil Rights Movement, an especially perilous role for a Black journalist like Bloice. By the early 1970s, Bloice was editor of the weekly People’s World, a West Coast Communist Party-affiliated publication, which had originated as a leading voice of the San Francisco waterfront battles of the 1930s.

Bloice hired Ringo first to write about class struggles and sports, he told Patrick Knowles in a 2004 City of the Hill, UCSC’s student paper, profile. “Soon he was doing all kinds of reporting. His thoroughness stood out and he never took things lightly, which was invaluable. But I think the main thing was that he was always thinking — he was one step ahead… Out of all the things I value in this life, it is people who are willing to ask the question ‘why’ and try to answer it. That is the way Conn has always approached work.” As Bloice left to cover the spiraling Watergate scandal, Ringo became the PW’s managing editor.

The PW had a remarkable crew. In addition to Bloice and Hallinan, there was William Allan, veteran labor reporter who had been one of the few reporters inside the auto workers GM sit-down strike of the 1930s, and the aforementioned Pele de Lappe, a talented social realist, print and paint artist, and friend of the Mexican titans Frieda Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

“He welcomed me, a very young and very headstrong activist, with open arms,” recalls Mark Allen, who also joined the PW around this time becoming one of its most facile, multi-faceted writers. “He was crucial to the functioning of the very best collective I was fortunate enough to be a part of. We worked together for 13 years and were friends and comrades ever since. Anyone who knew Ringo knew he was a talker, a talker about a lot of things. He had boundless curiosity, and a broad knowledge he wasn’t bashful about sharing, particularly after a glass of wine or a couple of pints of Guinness.”

“Ringo worked hard at understanding the world and provided thoughtful insight on the questions of war and peace,” Allen continues. “And of course, any discussion of British imperialism and its “unique” colonial experiment with Ireland could always get him to raise his voice and rise out of his seat. But even more uniquely, Ringo always listened, and he had a way of always making you feel heard. And that more than his encyclopedic knowledge made him the great teacher he was, both in and out of the halls of academia.”

“Til this day,” Bloice said in 2004, “when I am having trouble finding out what is going on in this world, I will call him up because I can be reasonably sure he knows what he is talking about.”

At the PW, Ringo became a go-to expert on all things military, from hardware and conflicts to excess spending, budget boondoggles and the human cost of war. Radey, himself an even more focused analyst on military matters, consulted regularly with Ringo on militarism topics and praised his knowledge and study. “He knew and read a great deal,” Radey says.

Ringo’s knowledge was especially expansive on his Irish heritage and its tortured legacy, global politics and world history. He was as comfortable writing about ancient Rome as he was about Soviet/Russian and Chinese policy, the wars of India and Pakistan, and unpacking the complex and painful lurches and turmoil in Israel, Palestine and the entire Middle East, all of which would become even more evident in his later column writings.

In 1979, Myerson became executive director of the U.S. Peace Council, an affiliate of the World Peace Council based in Helsinki, which worked to promote disarmament and global de-escalation of tensions and war. “I called on Ringo to write different pieces on the U.S.-Soviet nuclear arms race.” In 1985, “we were invited to send a couple of delegates to Khabarovsk in the Soviet Far East to ceremonies commemorating the 40th anniversary of the end of the Second World War and the victory over fascism. (Khabarovsk also included one of the USSR’s Jewish autonomous regions.) Who better to send than the distinguished Conn Hallinan, PhD, who knew more about not only the Red Army’s role in defeating the Third Reich, but also about Pershing missiles, ICBMs and the galaxy of contemporary US weapons of mass destruction.”

In 1982, Ringo began a new chapter in his life when he was hired to run the journalism program at UCSC and serve as “an inspiration to thousands of students., as his former student Patrick Knowles wrote in the 2004 City on a Hill profile upon Ringo’s retirement from UC Santa Cruz.

“Ringo’s pedagogy was infused with his politics,” relates Roz Spafford, former chair of the UCSC Writing Program. “He honored each student’s voice in the classroom and used his power as a faculty member and as a journalist to open doors for students who might not even know those doors were there. He also helped his students flourish by believing in them — not with generalized support or pep talks but with a very particular understanding of each student’s promise. Decades after they took his courses, he was still teaching them.”

In 2018, two-time Pulitzer Prize winning Associated Press reporter and author Martha Mendoza reflected on Ringo’s guidance, what she called a “life-changing moment” in her career. “My pivot moment came when I landed in Conn Hallinan’s journalism class. He was lively and engaging, and as angry as I was about the wrongs of the world. For the first time, I saw work I could do that had real meaning. Conn told me 30 years ago that I had enormous potential as a professional journalist. No one had ever said anything like that to me. I believed him, and still work to live up to his belief in me.”

“He was a remarkable teacher who inspired us to not just report and write about campus affairs and happenings, but also state, national and international stories that impacted us and our communities,” relates Kelly Whalen, a former UCSC student. “So many of us found ourselves, our voices and power, in his classroom and in the student paper he advised. He taught us how to report and write, but most importantly instilled in us that what we produced could shape our collective future.” In a letter to Ringo for his 80th birthday, Whalen described a special gift he gave her when she graduated, the book How the Irish Became White. It was inscribed “it’s time for you to spend a while with your roots (or tubers.)” This read, she said “would prove to be an important one, as I deepened my sense of identity and set out to make films that challenged the legacy of racism.”

Another former student Ian Sherr says, “his influence is in everything I write. Every time you read a nut graf in my stories, it should be in his voice. He taught me to constantly consider context and history, and to explore the endless ways they weave together. That passion for understanding has driven me to pursue the most important stories I’ve been fortunate enough to tell.”

After his UC retirement, Ringo devoted his knowledge and global curiosity to producing volumes of columns for Foreign Policy in Focus, and his own collection titled Dispatches from the Edge, reprinted in dozens of other publications. To read his voluminous writing catalog is to marvel at his creativity with the written word, the volume of his output, and the breath of his knowledge and expertise at such a diverse field of global topics.

In his later years, Ringo also employed his writing skills to fiction. “Even while he was very ill,” notes Roz Spafford, “Ringo wrote the last two novels in his Middle Empire’ Series, self-publishing a total of five volumes. Set in 249 AD, when the Romans occupied Spain, the books immerse you in the history, politics and even the romances of the time, all in Ringo’s unmistakable voice.”

Rick Ayers, University of San Francisco professor emeritus of education, recalls meeting Ringo while teaching journalism at Berkeley High in 1995 and learning from him. “Ringo took on all of this work with us out of his own ethical core as a teacher and activist. He taught me the radical possibilities of writing instruction and popular journalism. Beyond that, he was always enthusiastically regaling me with stories about the Roman legions (the invention of the non-commissioned officers), the folly of American foreign policy, and the legendary Hallinan family histories, including the longshoremen who provided security on the way to school for Ringo and his siblings. Yes, I’ve remembered all the stories and learned from Ringo’s example, his constant enthusiasm, his unlimited love for Anne and the family, and his curiosity, humor, and loyalty. I have been honored to call him a friend and comrade.”

Radey remembers Ringo as a “fantastic cook” and “a world class story teller with a fine collection of stories. We’ve all known leaders at some point in our lives. A lot of them have a problem. They look in the mirror in the morning, and go, “Wow! That’s impressive!” They are addicted to the microphone, and the mirror. They don’t listen, they talk. They have deep admiration, for themselves, and thinly veiled contempt for most of the rest of the world. This was never Ringo.”

“Of the many, many times I’ve been with Ringo over the years, I can think of few during which I didn’t learn something new,” says Myerson. “Want to know the best way to throw a punch? How about picking out vegetables at the Berkeley Bowl? What Yosemite teaches us about archeology? Ringo’s your go-to source. He can learn you about why Robert E. Lee was not only not a great general but was in fact a terrible one. He’ll explain how Marshall Georgy Zhukov and the Red Army wiped out Hitler best divisions which in turn allowed the British and U.S. D-Day invasion to be successful. Curious about what’s going on in Turkey? Brazil? India? Long-ago arms control negotiations? Ask him. And of course, the thousand-year struggle of the Irish against British colonialism will require a few meals and bottles of wine.”

Matthew describes Ringo’s “generosity, and a strong moral sense of right and wrong. You could trust Ringo to always consider your interest in whatever relationships you had. With Ringo, I always knew if I had a problem, he would do what he could to help me.”

I, too, worked with Ringo at the PW, writing and editing copy, and was another recipient of his political mentoring and brotherly gifts, including invited along on a couple of hearty Yosemite backpacking excursions, especially a memorable 30 mile, 5,000 foot hike down from White Wolf to Pate Valley and back up to Tuolumne Meadow. I remember cold rivers, rattlesnakes, a stubborn mule, and a night in beautiful Glen Aulin, where he artfully found a way to position our food high in the sky between trees where even hungry, frustrated bears who paid us a visit in the dark could not reach. We heard them trying.

One other memory from that trip. On hiking out, we were alerted by a family member to a report of a woman who had been injured far back down the trail. Ringo retraced our trail back down several thousand feet to Waterwheel Falls, hoisted her on his back, and carried her back up the trail to 8,000-foot Tuolumne Meadow to get medical help. As Matthew, who helped organize the trip and was also there, remembers, “he had a powerful moral sense of helping people who needed help. It was a guiding thing in his life, he always wanted to do the right thing.”

Who does that? Someone who always cares about others and is willing to put them first. Someone not steeped in “rugged individualism” and the “you’re on your own” mentality that is so intrinsic to the politics and plague of Trumpism today. Someone who believes in the notion of a commons, a shared obligation to others, not just ourselves. What I will most miss about Ringo is his humanity, his approach to young people and colleagues, to nurture, not torture, his empathy not disdain, encouragement not condescension, humility not arrogance, and always promoting the collective in pursuit of social justice for all.

Ringo is survived by his wife, Anne, sons Sean, Antonio, Brian, and David, and four grandchildren, Tyler, Vance, Mia, and Milo.

Spread the word