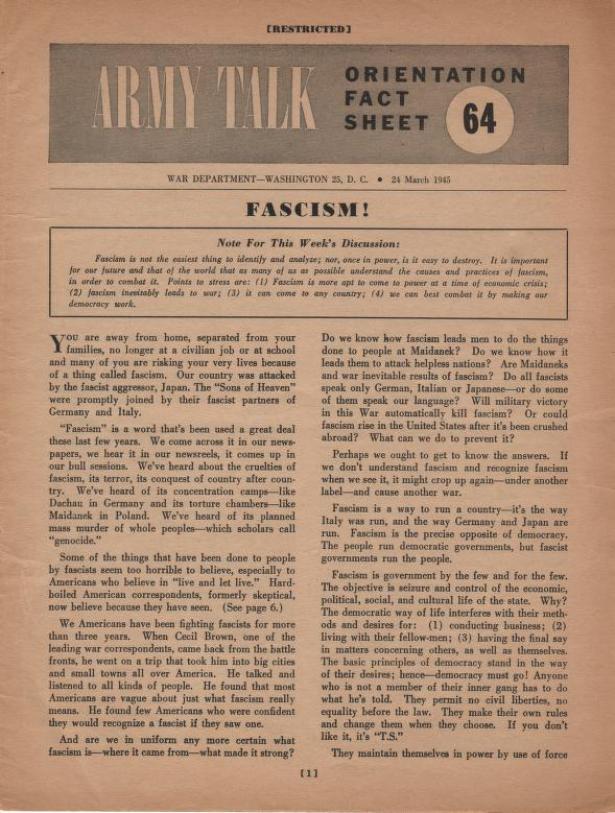

Beginning in 1943, the War Department published a series of pamphlets for U.S. Army personnel in the European theater of World War II. Titled Army Talks, the series was designed “to help [the personnel] become better-informed men and women and therefore better soldiers.”

On March 24, 1945, the topic for the week was “FASCISM!”

“You are away from home, separated from your families, no longer at a civilian job or at school and many of you are risking your very lives,” the pamphlet explained, “because of a thing called fascism.” But, the publication asked, what is fascism? “Fascism is not the easiest thing to identify and analyze,” it said, “nor, once in power, is it easy to destroy. It is important for our future and that of the world that as many of us as possible understand the causes and practices of fascism, in order to combat it.”

Fascism, the U.S. government document explained, “is government by the few and for the few. The objective is seizure and control of the economic, political, social, and cultural life of the state.” “The people run democratic governments, but fascist governments run the people.”

“The basic principles of democracy stand in the way of their desires; hence—democracy must go! Anyone who is not a member of their inner gang has to do what he’s told. They permit no civil liberties, no equality before the law.” “Fascism treats women as mere breeders. ‘Children, kitchen, and the church,’ was the Nazi slogan for women,” the pamphlet said.

Fascists “make their own rules and change them when they choose…. They maintain themselves in power by use of force combined with propaganda based on primitive ideas of ‘blood’ and ‘race,’ by skillful manipulation of fear and hate, and by false promise of security. The propaganda glorifies war and insists it is smart and ‘realistic’ to be pitiless and violent.”

Fascists understood that “the fundamental principle of democracy—faith in the common sense of the common people—was the direct opposite of the fascist principle of rule by the elite few,” it explained, “o they fought democracy…. They played political, religious, social, and economic groups against each other and seized power while these groups struggled.”

Americans should not be fooled into thinking that fascism could not come to America, the pamphlet warned; after all, “e once laughed Hitler off as a harmless little clown with a funny mustache.” And indeed, the U.S. had experienced “sorry instances of mob sadism, lynchings, vigilantism, terror, and suppression of civil liberties. We have had our hooded gangs, Black Legions, Silver Shirts, and racial and religious bigots. All of them, in the name of Americanism, have used undemocratic methods and doctrines which…can be properly identified as ‘fascist.’”

The War Department thought it was important for Americans to understand the tactics fascists would use to take power in the United States. They would try to gain power “under the guise of ‘super-patriotism’ and ‘super-Americanism.’” And they would use three techniques:

First, they would pit religious, racial, and economic groups against one another to break down national unity. Part of that effort to divide and conquer would be a “well-planned ‘hate campaign’ against minority races, religions, and other groups.”

Second, they would deny any need for international cooperation, because that would fly in the face of their insistence that their supporters were better than everyone else. “In place of international cooperation, the fascists seek to substitute a perverted sort of ultra-nationalism which tells their people that they are the only people in the world who count. With this goes hatred and suspicion toward the people of all other nations.”

Third, fascists would insist that “the world has but two choices—either fascism or communism, and they label as ‘communists’ everyone who refuses to support them.”

It is “vitally important” to learn to spot native fascists, the government said, “even though they adopt names and slogans with popular appeal, drape themselves with the American flag, and attempt to carry out their program in the name of the democracy they are trying to destroy.”

The only way to stop the rise of fascism in the United States, the document said, “is by making our democracy work and by actively cooperating to preserve world peace and security.” In the midst of the insecurity of the modern world, the hatred at the root of fascism “fulfills a triple mission.” By dividing people, it weakens democracy. “By getting men to hate rather than to think,” it prevents them “from seeking the real cause and a democratic solution to the problem.” By falsely promising prosperity, it lures people to embrace its security.

“Fascism thrives on indifference and ignorance,” it warned. Freedom requires “being alert and on guard against the infringement not only of our own freedom but the freedom of every American. If we permit discrimination, prejudice, or hate to rob anyone of his democratic rights, our own freedom and all democracy is threatened.”

—

Notes:

https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=armytalks

War Department, “Army Talk 64: FASCISM!” March 24, 1945, at https://archive.org/details/ArmyTalkOrientationFactSheet64-Fascism/mode/2up

*** *** ***

Related: This 1943 anti-Nazi film keeps going viral. It may be less effective than it seems.

by Alissa Wilkerson

Vox

Revised: June 29, 2018

A study of the short film Don’t Be a Sucker suggests old attitudes about fascism in America have never gone away.

In the hours following the Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in August of 2017, a short propaganda film called Don’t Be a Sucker, first produced in 1943 by the US Department of Defense and then re-released in 1947, went viral on the internet. And in the months since, it’s been repeatedly invoked on Twitter as a prescient harbinger of our current reality, 75 years after its creation.

Created as a warning against creeping fascism and racism in the United States, the movie illustrates the divide-and-conquer method employed by German Nazis. When the film was produced, the US had entered the ongoing war in Europe only two years earlier. Originally 20 minutes long, it was created by the Army Signal Corps to raise soldier morale, but an edited version was produced after the war and shown widely for educational purposes — including in cinemas.

Don’t Be a Sucker feels strangely timely today. But in 1951, researchers Eunice Cooper and Helen Dinerman published a study in the Public Opinion Quarterly analyzing the film’s effectiveness (it’s now accessible on JSTOR) — and their findings are just as timely and important as the film. Beyond that, they’re chilling.

Back in the 1940s, Don’t Be a Sucker drew links between Nazi Germany and American prejudice

Don’t Be a Sucker seems eerily prescient, depicting a man in a square railing against Catholics, “Negroes,” foreigners, and even Freemasons who take American jobs and threaten the American way of life. A good-looking ordinary American man named Mike stands nearby, nodding along, until a Hungarian-born man — a refugee from the Third Reich, given the historical context — takes him aside and explains how this method parallels the way Hitler and his followers divided the German population and set them at odds against one another: Jews, Catholics, Protestants, intellectuals, and native-born farmers whose egos were flattered by the Nazis.

“I’ve heard this kind of talk before, but I never expected to hear it in America,” the man tells Mike.

Mike, now understanding that fascists gain power for themselves by creating division among the common people, sees the error of his ways. He learns that it is only by presenting a united front against greedy authoritarian leaders that citizens can stand against tyranny.

Mike learns the error of his ways.

The film has been uploaded to YouTube many times — particularly since 2016 — but following the violent protests in Charlottesville, Don’t Be a Sucker once more made its way around social media.

Many contemporary viewers have pointed out that the film echoes the present. But Don’t Be a Sucker was an object of study in the past. And what the researchers uncovered may be an even grimmer reflection of today’s America, and offer a key takeaway that is good to remember when confronting the resurgence of white nationalist and supremacist rhetoric in the public square.

In the late 1940s, two researchers set out to study the limits of Don’t Be a Sucker

At the film’s more public rerelease in 1947 and 1948, Cooper and Dinerman — working with the Department of Scientific Research of the American Jewish Committee at the Institute of Social Research — explored how viewers’ attitudes were affected by the film, particularly those of high school students. They published their findings in 1951.

Cooper and Dinerman divided a group of high school students into a control group and an experimental group. Only the experimental group saw Don’t Be a Sucker. Four weeks later, both groups were asked to complete a questionnaire, which included some questions related to the message of the film and some control questions. The researchers divided up the answers by factors including the participants’ religious identity (though they only mention Jews, Catholics, and Protestants).

A Protestant preacher in Nazi Germany, as portrayed by Don’t Be a Sucker.

Each group responded strongly to the representation of their particular religious group being isolated and persecuted by Nazis. The film also appeared to have an effect on American-born Protestants who were somewhat prejudiced against Catholics and Jews; after seeing the film, they were about half as likely as the control group to agree with the statement that “in times of depression, it is only right that jobs should be given first to people born in America.”

Still, the numbers seem a bit surprising: After seeing the film, a quarter of the American-born Protestants in the experimental group agreed that people born in America deserved preferential treatment, contrasted with fully half the same segment of the control group.

Don’t Be a Sucker desensitized some viewers to the threat of fascism in America

But the researchers also found a “boomerang” effect in their subjects, which they define as the film having the opposite of its intended effect. They identify four specific “boomerang effects” that Don’t Be a Sucker had on the viewers in their study, but the most interesting for our time is this: Cooper and Dinerman discovered that students who viewed the film were more likely to agree with the statement that “what happened in Germany under the Nazis could never happen in America.”

This is actually the direct opposite of the film’s intended message. The researchers attribute it to the fact that while Don’t Be a Sucker takes pains to show the extent of the Nazis’ cruelty, it only shows one parallel to 1947 America: a man on a soapbox in a square, ranting about foreigners and “negroes” to a skeptical crowd. Many respondents saw the American as simply different from his German counterpart — though the American was giving a similar speech, only the German commanded the respect of a crowd.

One man seems half-convinced by the argument — Mike — but the subjects of the study found him weak, gullible, and passive. Mike only balks when the soapbox speaker rails against Masons (Mike himself is one), but he is quickly talked down by the Hungarian refugee.

The implication, to many of the viewers, was that American fascists are ineffectual and silly, quite different from their German counterparts, no matter how similar their ideology might be.

Don’t Be a Sucker made some viewers more complacent

Cooper and Dinerman also found that the students saw the man on the soapbox as a “lamebrain,” someone whom smart Americans knew to be a fraud and not worth their time.

“Believing that Americans in general would not be taken in by such talk,” they write, “these respondents regarded Americans who do applaud the agitator as uneducated, low-class, or in some other way inferior to themselves.”

They tested this statement with their questionnaire by including the statement: “In America, hardly anyone would listen to a man trying to spread race hate.” And to their surprise, they noticed a definite boomerang effect toward complacency among the students who were less prejudiced against people who were different from them: 29 percent of the students who had seen the film agreed with this statement, compared to 19 percent of those in the control group, who had not seen Don’t Be a Sucker, a result that Cooper and Dinerman called “quite startling.”

Furthermore, they found that 44 percent of those who’d seen the film agreed with the statement, “There are so many minorities in this country that no single one would ever be persecuted” — a sentiment that directly contradicts the film. Only 26 percent of those who hadn’t seen the film agreed with this statement.

“The inescapable conclusion is that the messages about Germany in this film, even when wholly understood, were not applied to America. A plausible hypothesis is that not only the German theme but its link with problems of discrimination seems to be ‘old hat’ to members of the audience,” Cooper and Dinerman wrote.

In other words, the link between fascist, racist sentiments in Nazi Germany and similar ideas as they surfaced in America (even just a few years after the fall of the Third Reich and the end of World War II) were too worn and “old hat” to make an impression on the audience. This bears out: Though the film shows a young black boy playing baseball with white boys, in 1947 America was still deeply segregated, with many white people not seeing a link between their attitude about black people and Nazi racism. (The film itself, after introducing the soapbox fascist as “anti-Negro,” focuses on Jews, Protestants, and Catholics, not race.)

And of course, the study participants were high school students, whose lives so far had been dominated by the looming threat of Nazis “over there,” but who as teenagers had naturally been immature in their understanding of the ideas that caused the heinous violence, and who had driven the conflict. They’d become desensitized.

Americans haven’t stopped thinking they’re too good to be taken in by fascist and racist ideas

Cooper and Dinerman’s paper goes on to evaluate the way Don’t Be a Sucker delivers its message, the limitations of its casting and its audience reach, and how future films of that ilk might convey their arguments more effectively. But two of their insights in particular seem striking in the context of today’s resurgence of white nationalist rhetoric: Don’t Be a Sucker’s viewers thought Americans were too smart to be taken in by fascists, and they were reluctant to draw parallels between Nazi rhetoric abroad and racist, anti-immigration rhetoric at home.

Mike is learning his lesson.

You could hear echoes of this during the Charlottesville events in 2017, whether in expressions of shock over events that many people had forecasted, the #ThisIsNotUs hashtag trending on Twitter that insisted the white supremacists who gathered in Charlottesville are not representative of most Americans, or the president’s initial refusal to specifically condemn the white supremacists who marched in his name. Both well-meaning and more pernicious sentiments abounded: that Americans are “better” than this, that the so-called alt-right are poor and ignorant rather than well-off and educated, that the actions of the Confederacy during the Civil War and of neo-Nazis today are anomalies, and the perpetrators should “go home.”

But others took a different view, pointing out that we can’t pretend racially motivated violence and hate isn’t an integral part of American history.

“The belief that America is somehow better than its white-supremacist history is sometimes an excuse masquerading as encouragement, and it’s part of the reason why the K.K.K. is back in business,” Jia Tolentino wrote at the New Yorker following the rally. “What happened in Charlottesville is less an aberrant travesty in a progressive enclave than it is a reminder of how much evil can be obscured by the appearance of good.”

To be wooed by authoritarian, fascist, divide-and-conquer rhetoric is to be a “sucker.” But thinking we’re too smart to be fooled, that it’s only crazies and lunatics who fall for this stuff — that’s what makes suckers of us all.

Heather Cox Richardson is an American historian. She is a professor of history at Boston College, where she teaches courses on the American Civil War, the Reconstruction Era, the American West, and the Plains Indians. She previously taught history at MIT and the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Subscribe to Letters from an American by Heather Cox Richardson

Alissa Wilkinson covers film and culture for Vox. Alissa is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics.

At Vox, we make complex topics easy to understand and help you navigate our world with clarity. Millions of people rely on this information, and in turn, we rely on our readers. We launched the Vox Membership program so you can go deeper with Vox, get involved in our mission, and support our journalism.

As a Vox Member, you’ll gain deeper access to our award-winning journalism and enjoy new member-only perks — all while helping ensure stable funding to support our work.

If you’re not ready to become a member, we appreciate one-time contributions of any size to help sustain Vox’s mission.

Spread the word