On Jan. 22, 1953, his first day as secretary of state, John Foster Dulles addressed a group of diplomats at his department’s still-new headquarters in Washington’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood. For years, the State Department had come under fire from Republicans and conservative activists as a haven for Communist spies and sympathizers — and not without reason, since one of its rising stars, Alger Hiss, had been convicted of perjury in January 1950 for lying about giving secret government documents to a Soviet spy.

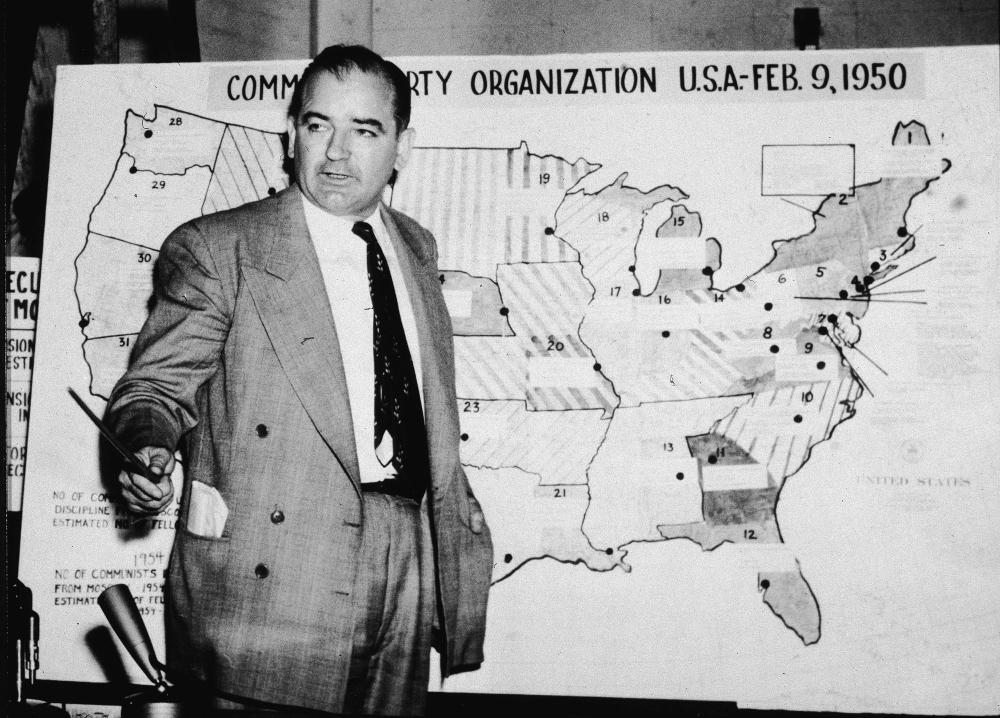

The failure to find more Hisses, and the fact that Hiss’ actions had taken place over a decade in the past, did nothing to appease men like Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who shot to national prominence just weeks after Hiss’ conviction with his claim to have a list of hundreds of spies within the State Department. By the time Dulles arrived that morning, public faith in the department, and morale within it, had cratered.

With his opening speech to his new employees, Dulles made clear that while he was their boss, he was not on their side. “Dulles’s words were as cold and raw as the weather” that day, wrote the diplomat Charles Bohlen. Dulles announced that starting that day, he expected not just loyalty but “positive loyalty” from his charges, making clear that he would fire anyone whose commitment to anti-communism was less than zealous. “It was a declaration by the Secretary of State that the department was indeed suspect,” Bohlen wrote. “The remark disgusted some Foreign Service officers, infuriated others, and displeased even those who were looking forward to the new administration.”

President Dwight Eisenhower and secretary of state John Foster Dulles talk at the White House in 1958. On Dulles' first day, he made clear to his employees that while he was their boss, he was not on their side. | Bill Allen/AP

So began what — until now — was the largest purge of “disloyal” government workers in U.S. history.

Similar scenes soon played out across the federal government under the new administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the first Republican elected president in two decades. Though the State Department was ground zero for the anti-communist purges, FBI agents scoured the files of thousands of employees across the federal government. In April 1953, Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450, which opened an energetic campaign to investigate thousands of potential security threats throughout the government.

“We like to think we are plugging the entries but opening the exits,” said White House press secretary James Hagerty.

Though the State Department was ground zero for the anti-communist purges, FBI agents scoured the files of thousands of employees across the federal government. | NARA

Over the next four months, 1,456 federal employees were fired, despite the fact that no one was ever found to be involved in espionage. Many were removed simply for being gay, which the order had explicitly defined as a security risk. Air Force Lt. Milo Radulovich was forced to resign his commission simply because his sister was a suspected communist. Others, like cartographer Abraham Chasanow, were pushed out on the basis on flimsy rumors of suspicious political beliefs.

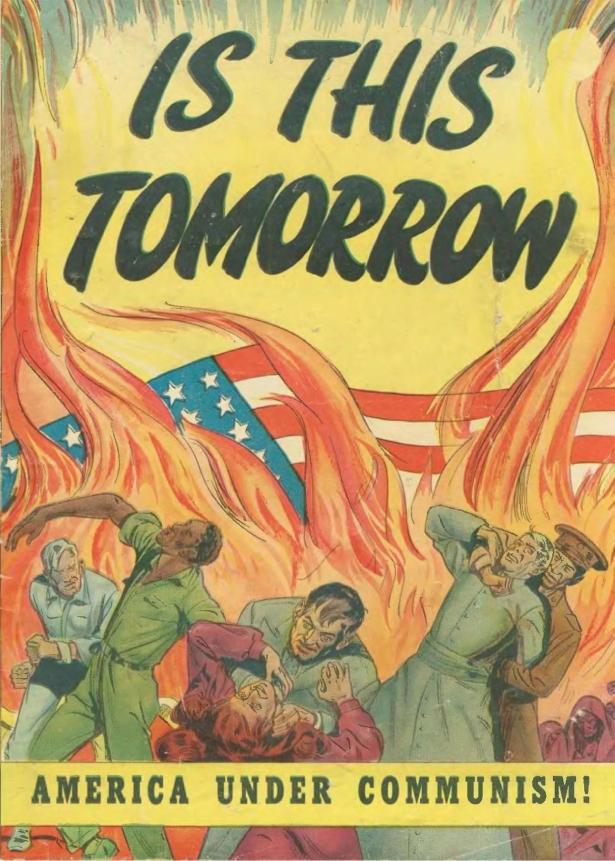

The widespread political purges of the early 1950s echo clearly today. Seventy years ago, the reasonable pretext of hunting Soviet agents opened the way to a yearslong, paranoid campaign, motivated by outlandish conspiracy theories, that destroyed countless careers but did nothing to improve America’s security.

Today, a stated desire to check the excesses of diversity, equity and inclusion programs has already been used to justify whirlwind firings and closures of entire federal offices. So it may be wise to consider the consequences of that previous era of purges, part of what came to be known as the “Red Scare.”

At a time of intense geopolitical competition, the United States kneecapped itself, removing thousands of valuable employees and forcing those who remained into unhappy conformity. It is hard not to see the same mistake being repeated today.

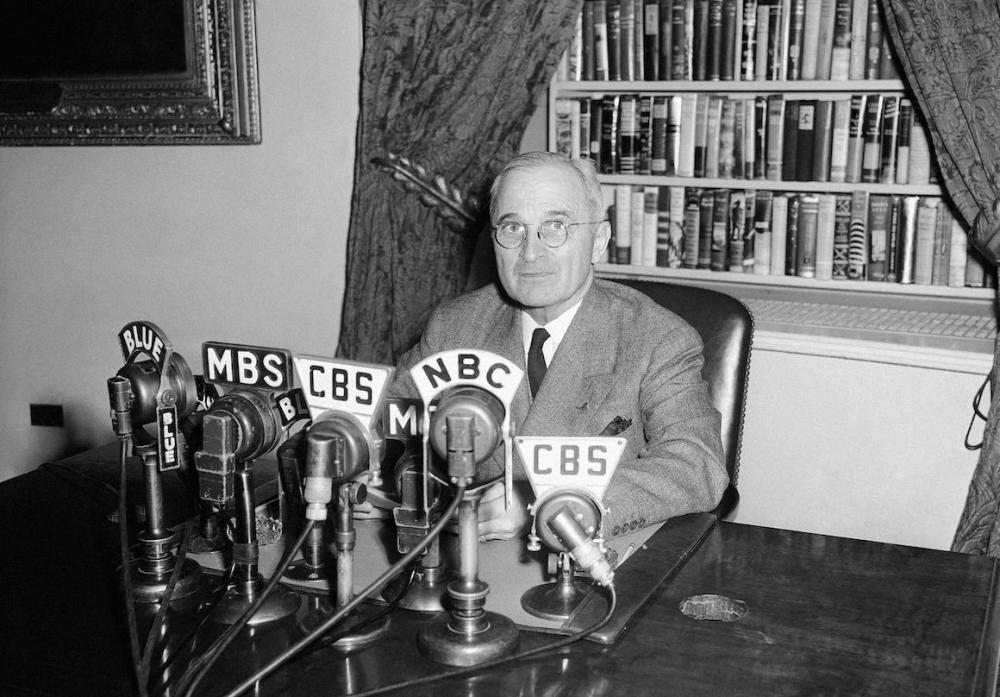

President Harry Truman speaks in 1945. Two years later, Truman issued an executive order to screen federal employees for "disloyalty." | AP

The hunt for disloyal public servants did not begin with Eisenhower and Dulles. Following the 1946 midterm elections, in which Republicans took control of both the House and the Senate with a campaign built on anti-communist attacks, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9835. It ordered the Civil Service Commission to screen the background of every current and new federal employee, well over a million people, for evidence of “disloyalty,” a term that was left ominously undefined. The screening drew on files from across the government, as well as police departments, former employers, even college transcripts. Truman also instructed his attorney general, Tom Clark, to devise a list of “subversive” organizations; current or former membership in just one would constitute a bright red flag.

If something suspicious came up in the initial screen, even the smallest doubt, the FBI would conduct a full field investigation, digging into every corner of a person’s life. Any derogatory information went into a file. It was then up to the department or agency involved to decide what to do with the employee. In theory, it might mean discipline or reassignment, though in practice most people who reached that point lost their job.

The flaws were apparent to anyone who took the time to read the order itself. Writing in The New York Times, a quartet of Harvard Law professors worried the program would “miss genuine culprits, victimize innocent persons, discourage entry into the public service and leave both the government and the American people with a hangover sense of futility and indignity.”

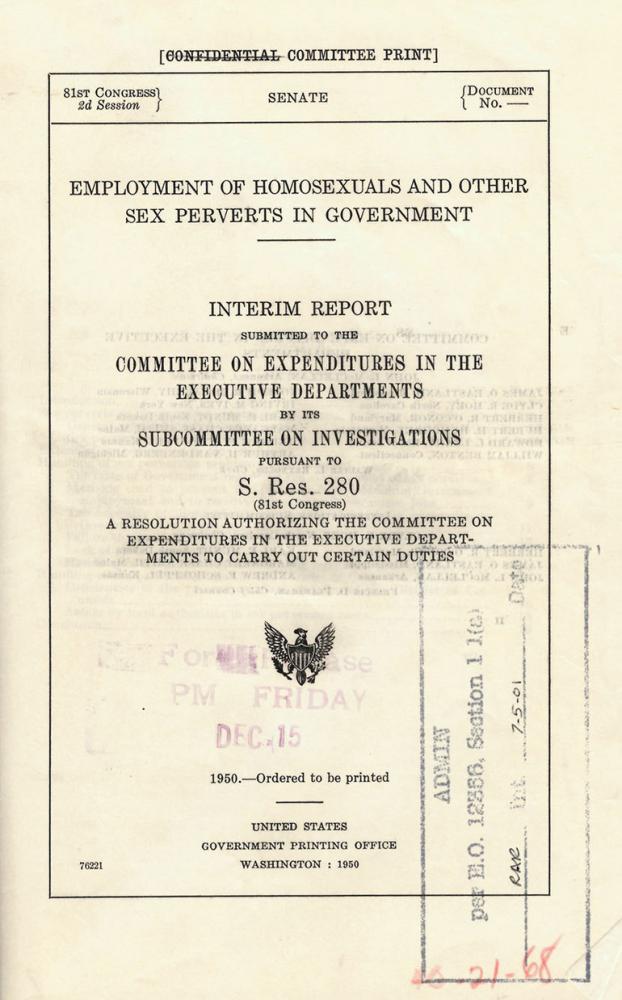

On Dec. 15, 1950, the Hoey committee released this report, concluding that homosexuals were "unsuitable for employment in the Federal Government" and constituted "security risks in positions of public trust." | NARA

And that is what happened. The loyalty program’s first director, Seth Richardson, insisted that the government had a complete right to discharge employees, “without extending to such employee any hearing whatsoever.” In one case, James Kutcher, who lost both his legs in World War II, was fired from the Veterans Administration because, a decade earlier, he had been a member of the Socialist Workers Party, an anti-Stalinist organization that Clark had nevertheless added to his subversives list.

Dozens of Black employees were subjected to harassing, invasive investigations because, outside of work, they were involved in civil rights activity, which was considered potentially subversive. The same happened to pro-labor employees. During its five and a half years in operation, Truman’s loyalty program conducted 4.76 million background checks, including 2 million current employees and 500,000 new hires each year. The screens resulted in 26,236 FBI investigations. Of those, 6,828 people resigned or withdrew their applications, and 560 were fired.

Not a single spy was ever discovered by the program. Its defenders argued that it succeeded by deterring potential subversives. But it also likely deterred many bright, talented people from applying in the first place, especially if they had dabbled in progressive politics in college. The same went for then-current federal employees: The order put a premium on submission and raised the price for individual expression.

While it is impossible to quantify a counterfactual, the cost of the anti-communist purges of the 1950s was clearly enormous and played out not just over the subsequent years but over decades. | Courtesy of Clay Risen

In his memoirs, Truman defended the rationale behind the program but admitted that it was deeply flawed in practice. He called the program the best he could do “under the climate of opinion that then existed.” To friends he admitted, “Yes, it was terrible.”

Among Truman’s targets were gay and lesbian employees of the government, especially in the State Department. In the retrograde spirit of the immediate postwar era, homosexuality was associated with weakness, femininity and progressivism. One writer, warning of the “sisterhood in our State Department,” wrote that “in American statecraft, where you need desperately a man of iron, you often get a nance.” In what later became known as the Lavender Scare, Congress ordered government agencies — from State to the American Battlefield Monuments Commission — to investigate any employee suspected of being homosexual, an ill-defined category that might mean anything from middle-age bachelorhood to, paradoxically, “Don Juanism,” or an energetic sex drive.

Yet another target were the so-called China Hands, a loose collection of academics and Foreign Service officers with deep experience in China. As the pro-Western Nationalists lost ground to the Communists under Mao Zedong during the Chinese Civil War following World War II, despite massive American support, the China Hands recommended caution, arguing that Mao’s victory was inevitable, and that U.S. policy could exploit cracks between him and Moscow. In retrospect, it was wise advice — but following Mao’s victory in 1949, it was taken as evidence that the China Hands had not only been “soft on communism,” but had been the core of a pro-communist conspiracy within the State Department.

One by one, the China Hands fell: Esteemed diplomats like John Stewart Service, John Paton Davies and O. Edmund Clubb were drummed out of the Foreign Service, some under Truman, others under Eisenhower. John F. Melby was dismissed simply because he had an affair with Lillian Hellman, a progressive playwright who had refused to “name names” before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The China Hands were relatively few in number, but the decimation of their ranks sent a clear signal to the rest of the foreign-policy establishment: Dissent at your own risk; retribution will be swift.

Sen. Joseph McCarthy testifies against the U.S. Army during the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954. The Wisconsin Republican shot to national prominence after claiming to have a list of spies in the State Department. | Getty Images

While it is impossible to quantify a counterfactual, the cost of the anti-communist purges of the 1950s was clearly enormous and played out not just over the subsequent years but over decades. For instance, had expertise not been purged and dissent not been punished so severely across the government during the early 1950s, wiser heads might well have raised the right objections to America’s short-sighted anti-communism in East Asia, above all its rush to intervene in Vietnam. Does the Trump administration run the same risk of short-sightedness today?

Spread the word