Annika Barber felt like an impostor as she boarded a bus just before sunrise on 24 February, and settled in for the long ride from New Jersey to Washington DC.

Barber had studied neuroscience for years before she launched her own laboratory at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. She had not trained to be an activist, yet now she was on her way to deliver a speech at a rally about proposed cuts to US research funding. When she arrived in Washington, she picked up a blank poster provided by rally organizers. “I would rather be in lab!” she wrote on it in big block letters.

Across the United States, researchers are navigating uncomfortable territory. Repeated threats to research funding and the mass firings of federal workers have pushed some scientists to take on unfamiliar roles as activists, speaking at rallies, calling legislators and forming new pressure groups. “Historically, scientists have done a really bad job of advocating for their own activities,” says David Meyer, a sociologist at the University of California, Irvine. “So this is a new challenge.”

Unaccustomed role

The events of the past six weeks have compelled many scientists to embrace that challenge. Soon after the second inauguration of US President Donald Trump on 20 January, the new administration attempted to freeze payments on federal grants; announced that it would review and potentially cancel any grant that mentioned terms it deemed indicative of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programmes; and issued dramatic cuts to the overhead, or ‘indirect costs’, paid on projects funded by the US National Institutes of Health.

“All of the bad news and the chaos made it hard to know what the best action to take was,” says Melissa Varga, science network senior manager at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington DC. “Folks just shut down.” Fear of retribution for speaking out also played a part, she adds.

The courts temporarily halted some of the Trump administration’s orders, but a coherent message has broken through: federal support for science is in danger. Gradually, scientists began to stir, Varga says: “They’re realizing now that doing any one thing is better than doing nothing.”

That activism is taking many forms. On 3 March, the Union of Concerned Scientists and 48 scientific societies released a joint letter to Congress calling for legislators to protect taxpayer-funded research. “The actions of this administration have already caused significant harm to American science and are risking the health and safety of our communities”, they said.

US researchers in planetary science are talking about creating a new professional society to strengthen their voice in policy matters. Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, says he has been thinking about such a society for several years. “But the recent attacks, because that’s what they are, on science in the US have catalysed the need for it,” he says. “The more organized the planetary-science community, the more effectively we can stand up and push back against these actions.” Byrne and others will lead a discussion at an upcoming planetary-science conference about whether to launch such a society.

Individual researchers also have a bounty of petitions to sign, including statements against censorship of science, indirect-cost reductions, and cuts to space science and biomedical research. And professional societies have circulated tip sheets to guide researchers who want to call their elected representatives.

Taking action

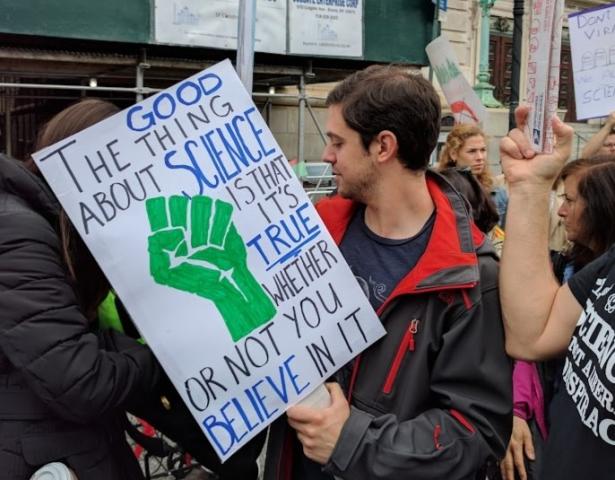

For many scientists, the big event is coming up on 7 March, at ‘Stand Up for Science’ rallies slated to take place in 32 cities around the country. The main event, in Washington DC, is spearheaded by a group of five researchers, most of them graduate students, who came together to combat their own initial feelings of powerlessness. “It’s been inspiring, as this has grown, to see how many people were feeling the same way and to take action,” says Emma Courtney, a graduate student in biology at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

Another goal is for each rally to spark local news outlets into covering the impact of science on that community, says Sam Goldstein, who studies women’s health at the University of Florida in Gainesville and is also co-organizing the Washington rally. Goldstein says that when she was interviewed by a Maryland newspaper, she researched the leading cause of death for the region, then came prepared with examples of how biomedical research could improve quality of life there.

Gathering with like-minded scientists at a large rally might be cathartic, but press coverage of protests can also backfire, says Anne Toomey, an environmental scientist at Pace University in New York City. Such events can deepen partisan divides if, for example, the local news focuses on angry signs that target Trump and leave Republican supporters feeling alienated. “If you want to convince Democrats to stand up for science, go ahead and march,” she says. “That’s not the audience we need to reach right now. That’s not who is in control of funding.”

Toomey also worries that some scientists have bombarded congressional offices with calls on a wide variety of issues. Instead, she’d like to see researchers coalesce around specific policy goals and develop relationships with congressional staffers. “If you really want to effect change, do what the lobbyists do,” she says. Some professional societies will already have expertise in lobbying Congress, she says, and researchers could support those efforts.

Small steps

One Washington DC organization, called 314 Action, hopes to help researchers do even more. Since 2017, the group has raised more than US$65 million to help elect Democrats with backgrounds in science and related fields. On 28 February, 314 Action announced a new goal to get 100 physicians elected to public office by 2030. Although the focus is on physicians, the organization expects public-health experts and other researchers to join the effort, says Raiyan Syed, national communications director for 314 Action.

Regardless of the path they choose, the key is for researchers to advocate for their work even at the risk of generating some backlash, says Meyer. “Nobody ever predicts what winds up working in advance,” he says. “If you get some people to take off their lab coats for an afternoon and go out to stand up for science, that’s a positive step.”

Are the Trump team’s actions affecting your research? Share information with Nature’s news team, or make suggestions for future coverage here.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00661-8

More articles by Heidi Ledford. More articles by Alexandra Witze.

Nature is a weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions. Nature also provides rapid, authoritative, insightful and arresting news and interpretation of topical and coming trends affecting science, scientists and the wider public. Nature's mission statement: First, to serve scientists through prompt publication of significant advances in any branch of science, and to provide a forum for the reporting and discussion of news and issues concerning science. Second, to ensure that the results of science are rapidly disseminated to the public throughout the world, in a fashion that conveys their significance for knowledge, culture and daily life.

Spread the word