By any measure, black tobacco workers in 1940s Winston-Salem, North Carolina were down at the bottom of the social hierarchy. They endured severe voting restrictions and segregated accommodations in public, all-powerful bosses and racist job assignments at work, and deplorable living conditions at home. America could trumpet its democratic commitments all it wanted — these workers’ lives were shot through with despotism.

In Civil Rights Unionism — originally released in 2003 and excerpted below — historian Robert Korstad tells the story of how these workers were able to change their conditions. After an explosion of shop-floor activism, the predominately black workforce successfully unionized the most powerful corporation in the city, R. J. Reynolds. Previously, supervisors had free rein to humiliate and degrade workers; now, after voting in the union — for many, the first election they’d ever participated in — workers sat across the table from their bosses and issued demands.

As Korstad’s title suggests, racial justice was at the heart of their union, Local 22 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America-CIO (FTA). Local 22 educated rank-and-file members about the political institutions they’d long been locked out of, created a vibrant internal culture that fostered a sense of pride and solidarity, and furnished workers with the organizational might to contest their political and economic disenfranchisement.

While the Communist-led union ultimately collapsed under the weight of red-baiting, the history of Local 22 reminds us of the essential role socialists played in the black freedom struggle — and provides us with a compelling portrait of anti-racist organizing and democratic struggle.

When CIO organizers first arrived in Winston-Salem in 1941, Robert Black was a lanky young baseball player who could barely imagine that a trade union might some day bring “that big giant,” R. J. Reynolds, “down to earth.” By the end of the war, Black not only stood at the helm of the South’s largest black-led local, he also found himself at the epicenter of a political struggle that turned on the enfranchisement and mobilization of the South’s black and white poor.

Local 22 had never limited itself to workplace demands. Even before it gained recognition, it had taken up broader civic issues, supporting the federal government’s wartime price controls; helping to defend William Wellman, a black North Carolina man, against a death sentence on a false rape charge; backing a black candidate for the Board of Alderman; and joining forces with the city’s dynamic young ministers to help blacks register to vote. Once established, the union put voting rights and education for active citizenship at the top of its agenda.

This linkage between union building and social transformation propelled Local 22 beyond the bounds of conventional trade unionism. As Black recalled, “After we built our union, we told the people that just to build a union is not going to solve all of our problems. . . . If you are going to defeat these people, not only do you do it across the negotiating table in the R. J. Reynolds Building, but you go to the city hall, you elect people down there that’s going to be favorable and sympathetic and represent the best interest of the working class.”

The CIO had spearheaded labor’s national political offensive by forming a semi-autonomous Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC) in the summer of 1943. Led by prominent trade unionist Sidney Hillman, CIO-PAC aimed to work from the local level up, not only to support the interests of labor but also to overcome the effective disfranchisement of thousands of poor and minority citizens throughout the country and thereby reinvigorate American political life, just as it had already tried to democratize economic life. Taking its cue from CIO-PAC, Local 22 formed its own Political Action Committee (PAC) in the spring of 1944 and threw itself into the congressional campaign.

Communist Party organizers, who became increasingly active in Winston-Salem after the war, helped to sharpen local unionists’ perception of the links between workplace democracy, social welfare, and black civil rights. Robert Black and other rank-and-file leaders found themselves not only fighting to make Local 22 a prime mover in the city’s political life but speaking for a national labor-based civil rights movement.

Civic Unionism and Civil Rights

In preparation for the 1944 election, FTA’s Washington representative, Elizabeth Sasuly, came down to help plan a voter registration drive. She carried with her the paraphernalia of CIO-PAC’s innovative media and educational campaign: posters, leaflets, and the usual how-to-do-it guides with titles such as What Every Canvasser Should Know, The CIO Political Action Radio Handbook, and a Speaker’s Manual.

She also brought special literature targeting women and African Americans; most striking was The Negro in 1944, a thirty-three-page publication filled with photographs that featured ordinary black citizens, often in integrated settings. Such materials contained a powerful message. They pictured black workers as they saw themselves: as citizens in a pluralistic society rather than as problems or pathological types. They also summoned both black and white workers to participation in a new kind of labor movement, one that included the diverse labor force that actually inhabited the country’s factories and mills.

Local 22’s efforts relied on the same vibrant networks and growing organizational skills that had powered its earlier organizing and voter registration campaigns. “We urged the crippled and the blind, everyone that could read or write to go to the polls,” Robert Black recalled. PAC members opened a booth at the black county fair, recorded spots for broadcast on the local radio station, and distributed leaflets at the plant gates. Going door to door in their neighborhoods, buttonholing workers during lunch breaks, speaking up during church meetings, and sponsoring citizenship classes on the US and North Carolina constitutions, unionists encouraged their friends and neighbors not only to stand up against trickery and intimidation but to overcome the insidious, internal barriers created by generations of political exclusion.

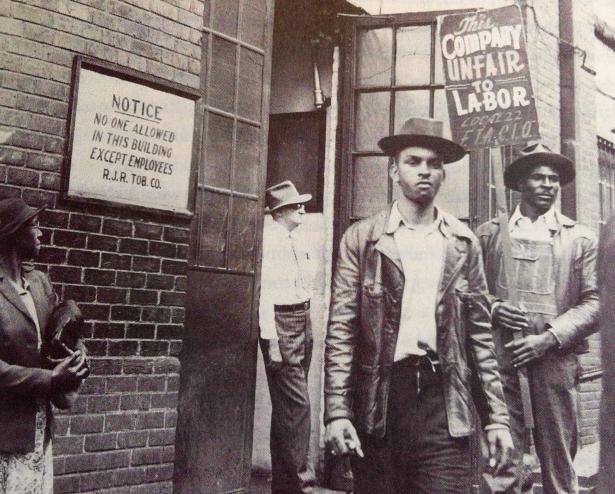

Tobacco workers in an R. J. Reynolds plant in Winston-Salem, North Carolina (date unknown).

Unionists encouraged their friends and neighbors not only to stand up against trickery and intimidation but to overcome the insidious, internal barriers created by generations of political exclusion.

Velma Hopkins and J. H. R. Gleaves explained just how this culture of exclusion worked. Hopkins was one of the few Local 22 activists who, with the help of a black doctor, had registered to vote before the union arrived. Yet the habits of Jim Crow kept even her away from the polls. “I didn’t take registration seriously until the union came in and we began to talk about PAC and the importance of voting,” Hopkins recalled. “The union taught us what each segment of government meant; what the aldermen and county commissioners controlled. We’d never heard nothing about them because they were all white.” Gleaves was a small business owner who had been active in the voting rights movement since the late 1930s. He pointed out that even in the midst of a war for democracy, registrars were still arbitrarily declaring that “some high school and college graduates . . . who can read and write the Constitution, not only in the English language, but often in several other languages,” were not qualified to vote.

The union’s tactics included effective negotiating as well as voter registration. For example, when Local 22 leaders held a public meeting with the county election board chairman to seek his cooperation in getting eligible voters on the books, he not only assured them that he supported the right of every “eligible” voter to register, he promised to look into the possibility of sending registrars to the union hall — an extraordinary reflection of the clout and credibility Local 22 had acquired. Even the Reynolds Tobacco Company bowed to the force of the workers’ desire to vote. According to Robert Black, the company gave voters “time off to go to the polls with no loss of pay for the first time in the history of North Carolina.”

Even so, individual registrars continued to reject qualified black voters. As Eleanore Hoagland remembered it, “People met in the union hall and went to where the registrar was en masse.” This show of collective force turned the tables on registrars who had long intimidated black voters; it yielded what the Winston- Salem Journal described as “record registration by Forsyth County citizens.”

On November 7, the voters of the Fifth District returned New Deal supporter John Folger to Congress and helped keep Franklin Roosevelt in the White House. Nationally, the CIO-PAC claimed a large share of the credit for enabling the Democratic Party to hold its own in the Senate and gain twenty seats in the House. Black workers in Winston-Salem, a large majority of whom had never voted before, had their first taste of successful political campaigning. The next month Robert Black told delegates to the FTA national convention in Philadelphia that Local 22 was responsible for 30 percent of the Democratic vote in Forsyth County.

As it turned out, Roosevelt’s reelection to a fourth term was a bittersweet victory. At the Democratic convention in Chicago, a showdown between the two wings of the party over Roosevelt’s running mate ended in defeat for Henry Wallace, who had the wholehearted support of CIO-PAC and of black leaders. With Roosevelt’s acquiescence, the nomination went to a relatively unknown senator from Missouri, Harry Truman, who had backed New Deal programs but whose roots lay in the party’s conservative wing.

Less noted, but equally portentous, was the effort of blacks representing South Carolina’s newly organized Progressive Democratic Party to challenge the seating of “Regulars,” who had barred black voters from the Democratic Party primary in defiance of the Supreme Court’s decision in Smith v. Allwright. The convention disqualified the Progressive Democratic Party, but its very presence symbolized the breadth and depth of black political mobilization.

Democracy at Home

As Winston-Salem celebrated the Allied victory and veterans began streaming back to town, Local 22 leaders looked ahead optimistically to what they hoped would be an expansion of democracy comparable to the changes that followed the Civil War.

FTA’s Elizabeth Sasuly made sure that the voices of Local 22’s most articulate leaders were heard at the highest levels of government. In November, Christine Gardner, a seasonal worker at Piedmont Leaf and a Local 22 member, traveled to Washington to address a Senate Education and Labor subcommittee considering a new minimum wage. The mother of three children described the difficulty she and her husband had making ends meet on a combined income of less than $40 a week. “My husband and I have been married ten years,” she testified, “during which time he has never had a suit of clothes. His greatest ambition is to buy for me a Christmas present, and for himself a complete set of clothes.” An interracial committee of male veterans from Local 22 boarded a plane on the morning of March 26, 1946, bound for the capital, where they met with President Truman to urge him to back the sixty-five-cent minimum-wage bill.

In the end, the Democratic Congress scuttled nearly every item on labor’s agenda. A filibuster by Southern congressmen defeated attempts to create a permanent Fair Employment Practices Committee, which would have posed a serious challenge to a regional economy that depended on systematic discrimination. Truman finally signed an Employment Act, but it was a pale imitation of the original. “We were kicked in the teeth by Congress,” one CIO official concluded.

Spread the word