[When Art Spiegelman wrote the introduction to a collection of vintage Marvel super-heroes, a passing negative reference to Trump was enough for the publishers to jettison the quality introduction.]

Back in the benighted 20th century comic books were seen as subliterate trash for kiddies and intellectually challenged adults – badly written, hastily drawn and execrably printed. Martin Goodman, the founder and publisher of what is now known as Marvel Comics, once told Stan Lee that there was no point in trying to make the stories literate or worry about character development: “Just give them a lot of action and don’t use too many words.” It’s a genuine marvel that this formula led to works that were so resonant and vital.

The comic book format can be credited to a printing salesman, Maxwell Gaines, looking for a way to keep newspaper supplement presses rolling in 1933 by reprinting collections of popular newspaper comic strips in a half-tabloid format. As an experiment, he slapped a 10 cents sticker on a handful of the free pamphlets and saw them quickly sell out at a local newsstand. Soon most of the famous funnies were being gathered into comic books by a handful of publishers – and new content was needed at cheap reprint rates. This new material was mostly made up of third-rate imitations of existing newspaper strips, or genre stories echoing adventure, detective, western or jungle pulps. As Marshall McLuhan once pointed out, every medium subsumes the content of the medium that precedes it before it finds its own voice.

Click here

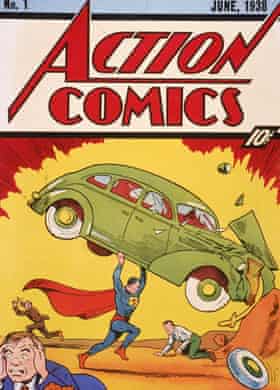

Enter Jerry Siegel, an aspiring teenage writer, and Joe Shuster, a young would-be artist – both nerdy alienated Jewish misfits many decades before that was remotely cool. They dreamed of the fame, riches and admiring glances from girls that a syndicated strip might bring, and developed their idea of a superhuman alien from a dying planet who would fight for truth, justice and the values of President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Barely out of childhood themselves, the boys’ idea was rejected by the newspaper syndicates as naive, juvenile and unskilled, before Gaines bought their 13 pages of Superman samples for Action Comics at 10 bucks a page – a fee that included all rights to the character. Not only was Siegel and Shuster’s creation the model for the brand new genre that came to define the medium, their lives were the tragic paradigm for creators bilked of the large rewards their creations brought their publishers.

Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were bilked of the large rewards their creations brought their publishers.

Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive // The Guardian

It is generally agreed that Superman launched the golden age of comics in June 1938 with his debut in Action Comics #1, published by what is now known as DC Comics. Siegel and Shuster had created a new archetype – or perhaps, more accurately, a new stereotype – and by 1940, once the nascent genre had demonstrated that it could get kids to part with millions of dimes per month, swarms of imitators catapulted hordes of four-colour heroes into the skies, all chasing the gold in this golden age. The juvenile naivety of Superman was, it seems, actually part of its allure, inviting youngsters into a new especially kid-friendly kind of story whose fantasies were even more unfettered by logic than most prose pulp fiction, all presented with diagrammatic visuals in primary and secondary colours that could make every page a theatre curtain to be raised on to new eyeball kicks and … action.

Superman's first appearance, in 1938.

Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images // The Guardian

Goodman, trend-surfing publisher of some lurid pulps, was one of the first to ride the superhero wave, immediately making a giant splash with his first issue of Marvel Comics in October 1939. (The first printing of 80,000 copies was followed by a reprint of 800,000 more.) The content was provided by Funnies, Inc, a comic book packager that could produce complete comics from concept to finished art for nascent publishers who wanted to keep their overheads low. These “shops” had something in common with the garment district sweatshops that many of the artists’ family members worked in. Usually done as piecework while punching a time clock with many hands (script-writers, pencillers, inkers and letterers) all attacking the original pages almost simultaneously, this was more a small industry than an art form.

It recruited green youngsters, washed up old hacks and even – when the second world war came along and drafted many of the young men who filled the growing demand for comics – women, people of colour and other interlopers. (Those interlopers, by the way, still had to provide the racist and sexist stereotypes that have long been a touchstone of the whole medium.)

At this point, it might be worth pointing out (not out of ethnic pride, but because it might shed some light on the rawness and the specific themes of the early comics) that the pioneers behind this embryonic medium based in New York were predominantly Jewish and from ethnic minority backgrounds. It wasn’t just Siegel and Shuster, but a whole generation of recent immigrants and their children – those most vulnerable to the ravages of the great depression – who were especially attuned to the rise of virulent antisemitism in Germany. They created the American Übermenschen who fought for a nation that would at least nominally welcome “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free … ”

Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, co-creators of Captain America.

Photograph: Anonymous/AP // The Guardian

To namecheck just a few of these secular Jews who had adopted Clark Kent-like secret identities: Gaines was born Max Ginzberg; Goodman’s parents immigrated from Vilnius, Lithuania; Jack Kirby (né Jacob Kurtzberg), the powerhouse who co-created Captain America with his landsman Joe Simon, was born in the slums of New York’s Lower East Side; and Stan Lee, who became the face of Marvel Comics, was Goodman’s wife’s cousin, nepotistically hired as a 17‑year-old office boy named Stanley Lieber. Though not welcome in the higher precincts of advertising and publishing, they were all able to find their niche at the bottom of the barrel.

The unseasoned artists in these comics factories discovered the possibilities of a new form while under do-or-die deadline pressures. They picked up their skills by copying each other and by stealing directly from the masters of the newspaper adventure comics: Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon, Secret Agent X-9), Hal Foster (Tarzan, Prince Valiant) and Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates). On the other hand, Carl Burgos (né Max Finkelstein), who created the lead feature in Marvel Comics #1, The Human Torch, proudly said: “If they wanted Raymond or Caniff they could look at Raymond or Caniff. The miserable drawing was all mine.” A writer-artist, his then rudimentary drawing skills were buttressed by an intuitive visual storytelling ability and were applied to an inspired character: The Human Torch. The character – an anthropomorphised streak of red and yellow flame – had a graphic intensity that burned its way into readers’ eyeballs and personified the raw crackling energy of the early comic books before they were domesticated.

William Blake “Bill” Everett, Burgos’s comrade at Funnies, Inc, was an oddity in comics. For one thing, he wasn’t Jewish. Everett came from a 300-year-old patrician Massachusetts family and he really was a direct descendant of his namesake. He came to the outsider status that drew him to comics via an addictive personality – he was a heavy drinker from the age of 12 and had a three-pack-a-day cigarette habit – or maybe it was an outsider’s sensibility that drove him to drink. He was one of the most gifted artists ever to work in comic books. He drew fluidly, was comfortable in many genres, and had a sense of page design that allowed the reader’s eye to find buried visual treasures while swimming effortlessly through a story.

His alienated antihero, Namor, the Sub-Mariner, was the forefather of a long line of troubled characters that would populate the Marvel universe a couple of decades later. In the 1940s the Sub-Mariner was singular – a marked contrast to the square and square-jawed vigilante do-gooders who lived in the less scruffy DC Comics neighbourhood. Never fully at home in the ocean or in the air, Namor was proud, arrogant and more volatile than the Human Torch, his complementary opposite. But water and fire combined to bring Marvel Comics to an elemental boil.

In late 1940, over a year before Pearl Harbor, while the Nazis were Blitzkrieging London, Simon, an entrepreneurial freelancer for Funnies, Inc, was hired by Goodman to write, draw and edit for him directly. Simon showed him the cover concept for a new superhero that he and Kirby had dreamed up – a hero dressed like an American flag with giant biceps and abs of steel has just burst into Nazi headquarters and knocked Hitler over with a haymaker to the jaw. Goodman began to tremble, knowing what an impact this book would make and remained anxious until the first issue of Captain America, dated March 1941, landed on the stands. Goodman had been terrified that someone might assassinate Hitler before the comic book came out!

Captain America was a recruiting poster, battling against the real Nazi super-villains while Superman was still fighting cheap gunsels, strike breakers, greedy landlords and Lex Luthor – and America was still equivocating about entering the conflict at all. No wonder Simon and Kirby’s comic book became an enormous hit, selling close to a million copies a month throughout the war. But not everyone was a fan in 1941 – according to Simon, the German American Bund and America Firsters bombarded the publisher’s offices with hate mail and obscene phone calls that screamed “Death to the Jews!” Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, a real-life superhero, called to reassure him, saying: “The city of New York will see that no harm comes to you.”

`I love the form of comics' ... a collection of Marvel issues.

Photograph: Alamy // The Guardian

Kirby’s hyperkinetic figures with hypertrophied muscles left human anatomy in the dust. His characters were bellicose, humourless, single-minded and angry as they burst out of saw-toothed panels and widescreen spreads. His art set the tone for superheroic action, not just during the war years, but ever since.

I know that Kirby was a protean original as a comic book creator as well as a genuine war hero, but I confess that I have a blind spot when it comes to the superhero genre that grew out of the template he set. Even when I was 12, superheroes were my methadone – I was deeply addicted to satire magazines such as Mad, and the old newspaper comics I discovered in my public library’s bound volumes. I preferred more mature fare like Donald Duck and Little Lulu. You see, I love the form of comics – the pages full of co-mixed words and pictures butting up against each other, all those little boxes you have to compare and contrast to pry out the narrative juice; and I adore the weird idiosyncrasies of cartoon language in all its accents.

Those who find superheroes the alpha and omega of comics date the end of the golden age to some time in the postwar 1940s when interest in the genre faded.

Disenchanted GIs, no longer an eager and captive audience, may have realised that it wasn’t Captain America who won the war. Maybe it was the Russians! In any case, demobilised soldiers either grew out of the comic book habit or shifted their attention to other genres. Crime, cowboy, romance, horror and war-themed comics flourished, often with more mature – and even lurid – content designed for older readers.

I date the end of the golden age to 1954. A moral panic built on the false assumption that the medium was strictly for young kids and was turning them into juvenile delinquents had led to comic-book burnings and to US Senate hearings that ultimately put many publishers out of business and maimed the rest. Sanitised superheroes brought the medium off life support in 1956 (now hailed as the beginning of the silver age) but the medium never regained the ubiquity it had in its heyday – as comic books. As movies, they have conquered the world!

Back in the golden age, if you wanted to see some guy in a cape fly over a skyscraper or turn New York City into rubble, comic book panels were the most satisfying delivery system. In the 21st century, thanks to the miracle of CGI, many millions of people around the globe who have never read a comic or heard of graphic novels go to their multiplexes to worship the new deities that embody the DNA of comics.

The Red Skull in Captain America: The First Avenger (2011).

Photograph: Allstar/Marvel Studios // The Guardian

The young Jewish creators of the first superheroes conjured up mythic – almost god-like – secular saviours to deal with the threatening economic dislocations that surrounded them in the great depression and gave shape to their premonitions of impending global war. Comics allowed readers to escape into fantasy by projecting themselves on to invulnerable heroes.

Auschwitz and Hiroshima make more sense as dark comic book cataclysms than as events in our real world. In today’s all too real world, Captain America’s most nefarious villain, the Red Skull, is alive on screen and an Orange Skull haunts America. International fascism again looms large (how quickly we humans forget – study these golden age comics hard, boys and girls!) and the dislocations that have followed the global economic meltdown of 2008 helped bring us to a point where the planet itself seems likely to melt down. Armageddon seems somehow plausible and we’re all turned into helpless children scared of forces grander than we can imagine, looking for respite and answers in superheroes flying across screens in our chapel of dreams.

While the content of comic books has hijacked our cinema, the form of comics – cleverly disguised as graphic novels – has infiltrated what’s left of our literary culture. When the Folio Society, venerable publisher of luxurious illustrated books since 1947, decided to plunge in with a deluxe compilation of golden age Marvel comics, they invited me, as a graphic novelist and comic book scholar, to write an introduction to the book. Perhaps they misguidedly figured that I might lend the endeavour a fig leaf of respectability.

Click here

I turned the essay in at the end of June, substantially the same as what appears here. A regretful Folio Society editor told me that Marvel Comics (evidently the co-publisher of the book) is trying to now stay “apolitical”, and is not allowing its publications to take a political stance. I was asked to alter or remove the sentence that refers to the Red Skull or the intro could not be published. I didn’t think of myself as especially political compared with some of my fellow travellers, but when asked to kill a relatively anodyne reference to an Orange Skull I realised that perhaps it had been irresponsible to be playful about the dire existential threat we now live with, and I withdrew my introduction.

A revealing story serendipitously showed up in my news feed this week. I learned that the billionaire chairman and former CEO of Marvel Entertainment, Isaac “Ike” Perlmutter, is a longtime friend of Donald Trump’s, an unofficial and influential adviser and a member of the president’s elite Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, Florida. And Perlmutter and his wife have each recently donated $360,000 (the maximum allowed) to the Orange Skull’s “Trump Victory Joint Fundraising Committee” for 2020. I’ve also had to learn, yet again, that everything is political... just like Captain America socking Hitler on the jaw.

[Essayist Art Spiegelman is an American cartoonist, editor, and comics advocate best known for his graphic novel Maus, a history of his father's time in Germany and as a survivor of Hitler's concentration camps. His work as co-editor on the comics magazines Arcade and Raw has been influential, as was his decade-long sojourn as contributing artist for The New Yorker. The full story of Marvel's pulling Spiegelman's essay, "Spiegelman’s Marvel essay ‘refused publication for Orange Skull Trump dig’ is by the Guardian's Alison Flood HERE.]

Catch up on the issues that matter. Subscribe to The Guardian.

Spread the word