In the mid-20th century, federal, state and local governments pursued explicit racial policies to create, enforce and sustain residential segregation. The policies were so powerful that, as a result, even today blacks and whites rarely live in the same communities and have little interracial contact or friendships outside the workplace.

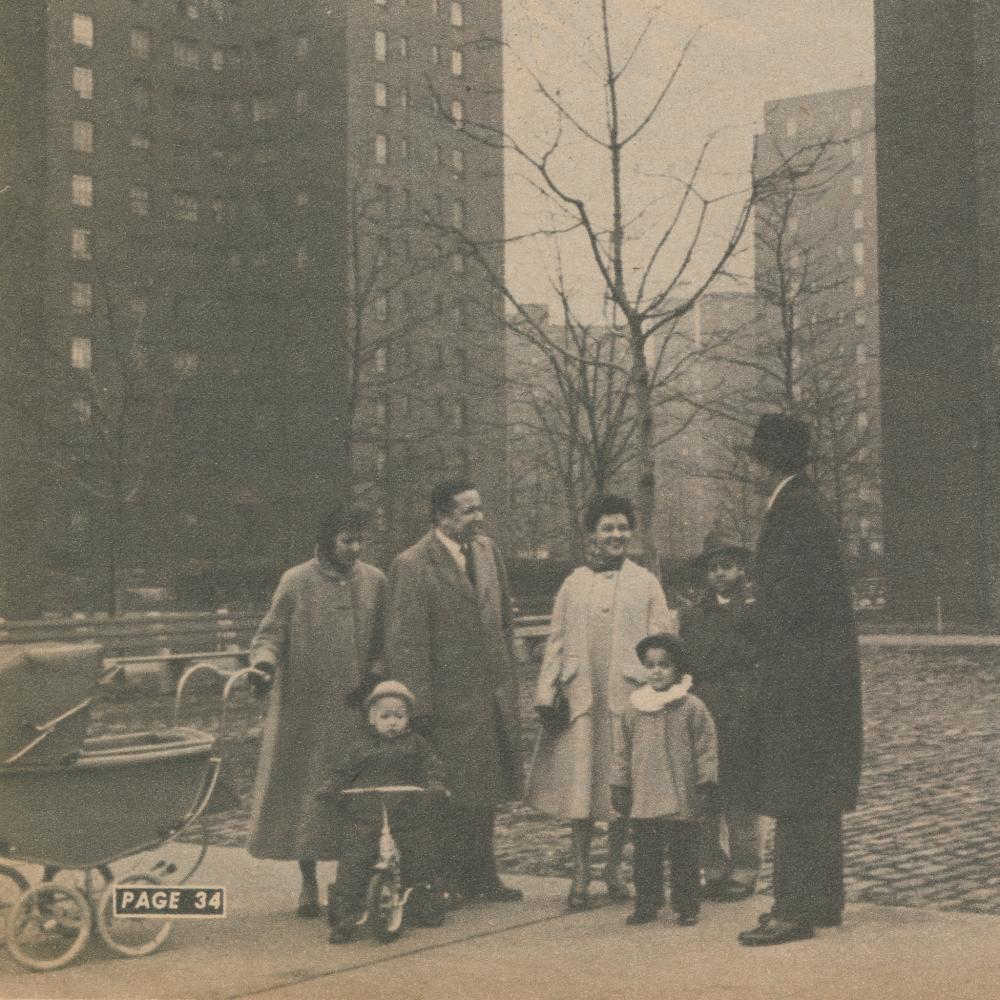

This was not a peculiar Southern obsession, but consistent nationwide. In New York, for example, the State legislature amended its insurance code in 1938 to permit the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to build large housing projects “for white people only” — first Parkchester in the Bronx and then Stuyvesant Town in Manhattan. New York City granted substantial tax concessions for Stuyvesant Town, even after MetLife’s chairman testified that the project would exclude black families because “Negroes and whites don’t mix.” The insurance company then built a separate Riverton project for African-Americans in Harlem.

Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection, via Getty Images // The New York Times

Credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library // The New York Times

A few years later, when William Levitt proposed 17,000 homes in Nassau County for returning war veterans, the federal government insured his bank loans on the explicit condition that African-Americans be barred. The government even required that the deed to Levittown homes prohibit resale or rental to African-Americans. Although no longer legally enforceable, the language persists in Levittown deeds to this day.

State-licensed real estate agents subscribed to a code of ethics that prohibited sales to black families in white neighborhoods. Nationwide, regulators closed their eyes to real estate boards that prohibited agents from using multiple-listing services if they dared violate this code.

In many hundreds of instances nationwide, mob violence, frequently led or encouraged by police, drove black families out of homes they had purchased or rented in previously all-white neighborhoods. Campaigns, even violent ones, to exclude African-Americans from all but a few inner-city neighborhoods were often led by churches, universities and other nonprofit groups determined to maintain their neighborhoods’ ethnic homogeneity. The Internal Revenue Service failed to lift tax exemptions from these institutions, even as they openly promoted and enforced racial exclusion.

Each of these policies and practices violated our Constitution — in the case of federal government action, the Fifth Amendment; in the case of state and local action, the 14th. Our residential racial boundaries are as much a civil rights violation as the segregation of water fountains, buses and lunch counters that we confronted six decades ago.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order prohibiting federal agencies from continuing to promote housing segregation. In 1968, in the wake of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act, which made racial discrimination in the sale and rental of housing unlawful for private actors as well as government.

Credit: Buyenlarge/Getty Images // The New York Times

Credit: Rolls Press/Popperfoto, via Getty Images // The New York Times

But the Fair Housing Act was inadequate to undo the damage our government had previously wrought. Patterns were set and have been difficult to reverse. The enormous black-white wealth gap, for example, responsible for so much of today’s racial inequality, is in large part a product of black exclusion from homes whose appreciation generated substantial equity for white working-class families with F.H.A. and V.A. mortgages that propelled them into the middle class.

Even if federal, state and local officials, along with banks, insurance companies and real estate brokers, no longer intend to discriminate by race, their policies can sometimes have that effect, reinforcing and perpetuating segregation. Since the very first days of the Fair Housing Act, all 11 of the federal appeals courts that have considered the question — and, more recently, the Supreme Court, in Texas v. Inclusive Communities Project, have said the act prohibits not only intentional segregation, but also policies and practices whose effect is to discriminate for no defensible reason, even if there is no evidence of a racial motive. Lawyers describe such actions as having a “disparate impact” on minorities.

Now, however, the Trump administration is about to put into effect procedures to make it virtually impossible to prove disparate impact, no matter how egregious a discriminatory policy or practice may be.

This fall, reporters at Syracuse.com demonstrated that homeowners in low-income, predominantly minority neighborhoods in Syracuse have been paying higher property taxes than they lawfully should. The cause of this “disparate impact” is Syracuse’s unlawful failure, since 1996, to conduct an up-to-date citywide property reassessment. Over the next decades, market values of homes in white neighborhoods have risen much more than market values of homes in black ones. As a result, homeowners in white neighborhoods have tax assessments that are too low compared with the value of their homes, so these homeowners pay a smaller share of the total city tax bill than they should. Homeowners in low-income neighborhoods, it follows, are paying a higher share than they should.

There are many reasons for the smaller growth of home market values in heavily minority low-income neighborhoods than in higher-income neighborhoods over the last quarter-century, many of them rooted in the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow. But one cause is more recent: During the lead-up to the financial meltdown of 2008, black and Hispanic homeowners were targeted by mortgage sales firms to refinance properties with new loans that had enticingly low initial interest rates. But the rates exploded into much higher charges a few years later, a result described in the small print of loan documents but one that salespeople rarely highlighted. These “subprime” loans were often marketed to minority homeowners who were fully qualified for mortgage terms like those offered to white suburban homeowners. When the subprime rates escalated, many borrowers were unable to make their monthly payments, and banks foreclosed on their homes. Banks and other mortgage holders boarded up the foreclosed properties, and often failed to mow the lawns or otherwise maintain them in good condition. The eyesores drove market values down for surrounding properties as well.

Credit: Alex Wong/Getty Images // The New York Times

Property tax calculations follow a similar procedure everywhere. Assessors value all homes in a city (or, in some places, county) at the same percentage of market value. It doesn’t have to be at 100 percent of market value, but to be fair it must be at the same percentage of real market value in every neighborhood. The total of all assessed values is then divided into the total budgets of schools, libraries, fire and police departments and other agencies to calculate a citywide tax rate. This citywide rate, multiplied by a home’s unique assessed value, determines the property tax the homeowner must pay. So if assessments in black neighborhoods are a higher percentage of true market values than assessments in white neighborhoods, black homeowners pay an unfairly larger share of public service costs than white homeowners do. This exacerbates racial inequality and reinforces the racial segregation that was unconstitutionally created a half-century and more ago.

If ever there was a policy that had a disparate impact on African-Americans, Syracuse’s obdurate refusal to keep its assessments up-to-date would be it. Under current Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) rules, families in Syracuse’s black neighborhoods can file a complaint with HUD alleging that the illegally out-of-date assessment system has a disparate impact upon homeowners like themselves, violating the Fair Housing Act. To start the legal process, they would simply have to show that the assessment delay had caused African-Americans unfairly high tax payments. The city would then have to try to defend the delay by showing it had a legitimate justification for failing to keep assessments up-to-date. Even if the city did so, the homeowners could still prevail by showing that there was a reasonable alternative to the city’s practice that would not have such a discriminatory effect.

The proposed Trump Administration rule throws up many technical roadblocks to filing and pursuing such a complaint, but one new procedural hurdle wouldn’t even let the black homeowners get in the door: Before the city would be required to provide a rationale for its failure to keep assessments current, the complainants would have to imagine every conceivable justification that the city might assert, and prove that each was not legitimate, without knowing what actual defense the city might claim or what standard of legitimacy HUD would impose. If the city then came up with a justification that the homeowners hadn’t refuted to HUD’s satisfaction (for example, that following state law requiring timely reassessments would be too costly), HUD could dismiss the disparate impact action. A process that requires complainants to refute defenses that haven’t yet been offered is one that is designed to block civil rights, not protect them.

In the many decades in which civil rights groups have brought disparate impact claims under the Fair Housing Act, no court has ever required such obstacles to having a disparate impact claim heard. Yet HUD proposes to impose them. Few minority plaintiffs will have the resources to hire the teams of lawyers who can jump through the hoops HUD is erecting, and then to take defendants to court after HUD has dismissed a complaint on spurious procedural grounds.

HUD’s excuse for promulgating its new rule has been that the modification is required to comply with the 2015 Supreme Court ruling (in Texas v. Inclusive Communities) that upheld the use of disparate impact claims to enforce the Fair Housing Act. But the excuse is patently false. The court’s opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, who is now retired, listed some recent cases in which an analysis of disparate impact was necessary to properly enforce the Fair Housing Act. One, for example, originated in St. Bernard Parish, an almost-all-white county bordering New Orleans. The county came up with one device after another to exclude African-Americans whose homes had been destroyed in Hurricane Katrina and who might try to resettle in the county.

The first was a racially motivated “blood relative” ordinance, prohibiting any single-family homeowner from renting his or her home to someone who was not a close relative. A federal court ordered the county to repeal the ordinance and to sign an agreement that going forward it would obey the Fair Housing Act’s prohibition on racial discrimination.

When a developer then proposed to build a mixed-income apartment complex, St. Bernard officials announced a moratorium on issuing permits, so the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center went to court, claiming that the county not only breached the agreement but also violated the Fair Housing Act. The housing group showed that a disproportionate share of potential renters would be African-Americans who had been displaced by the hurricane, and contended that there was no reasonable basis for prohibiting the project to proceed.

Credit: Alex Brandon/Associated Press // The New York Times

The county then had to justify its action, and came up with six reasons. It claimed that medical facilities in the county were insufficient to support the project’s renters, although a new 40-bed hospital had been announced months earlier. It claimed that the county was already “flush” with rental housing, although even if the proposed project went forward, only 20 percent of the county’s pre-Katrina rental units would be replaced. It claimed that the builder of the proposed project was likely to abandon it after construction, although the builder would have to repay all the federal tax credits upon which it relied if the property were not maintained in good condition for at least 15 years. It claimed that the moratorium on new apartment construction was needed because the City Council wanted to prevent a different, lower-quality project, from being built, although council members had specifically cited the developer’s project when announcing the moratorium. And it claimed that the moratorium was needed to give the county time to update its zoning code, although from announcement of the moratorium to a court hearing six months later, the county had undertaken no efforts to update its zoning code. The court found that none of these explanations justified the policy, and since the moratorium had a disparate impact on African-Americans, St. Bernard Parish must withdraw its moratorium, permitting the construction.

Under the administration’s proposed new rule, builders and civil rights groups could never win such a case at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, even though Justice Kennedy cited the case as exactly the kind that civil rights complainants should be able to win. Under the new rule, the plaintiffs would, in filing their complaint, have to specify the six excuses the county might come up with to justify its moratorium and show why that possible excuse was not reasonable or necessary. Until the complainants had demolished, in advance, these conceivable excuses, the parish would not even be required to respond to the complaint. Civil rights groups should not be required to write fantasy novels before asserting their rights under law.

HUD’s previous rule that the Trump administration proposes to replace defined a policy or practice that has an unlawful disparate impact as one that “creates, increases, reinforces, or perpetuates segregated housing patterns because of race.” The proposed rule eliminates the reference to segregation. This matters because established racial segregation, not ongoing discrimination alone, underlies so many of our most serious social problems, including racial disparities in education, health, criminal justice and wealth that, by the time Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, had become entrenched nationwide, and persist to this day.

Credit: Andrew Harnik/Associated Press // The New York Times

It is not entirely surprising that the proposed rule would ignore this crisis. HUD’s secretary, Ben Carson, has said that efforts to remedy racial segregation are a form of “social engineering” that should be avoided. HUD’s proposed new disparate impact rule makes a mockery not only of the Supreme Court but also of the Fair Housing Act itself.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration proposed another Fair Housing Act rule, eviscerating yet another important remedy for racial segregation. Federal appellate courts and the Supreme Court have concluded that the act was designed not only to prevent ongoing discrimination but also to create “truly integrated and balanced living patterns.” This aspect of the act was, for 50 years, largely ignored until the Obama administration required cities and towns to assess the obstacles to integration in their own communities and propose effective plans to overcome them. This second newly proposed HUD rule effectively relieves jurisdictions from an obligation to desegregate and virtually reduces the Fair Housing Act to a tool that can be used only to combat racially explicit discrimination.

The Trump administration’s hostility to justice for racial minorities continues unabated.

[Richard Rothstein is a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute and the author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”]

Spread the word