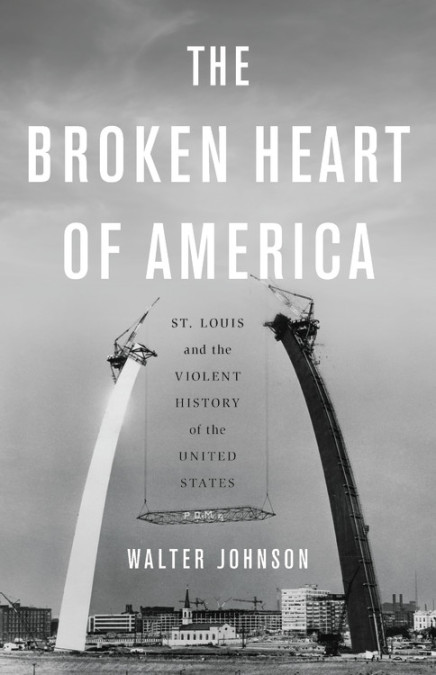

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

By Walter Johnson

Basic Books; 528 pages

April 14, 2020

Hardback: $35.00

ISBN-13: 9780465064267

A century ago, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about St. Louis, a city that “sprawls where mighty rivers meet,” and offered an autopsy of a tragedy. In the summer of 1917, after a labor dispute at an aluminum plant, black residents of East St. Louis were chased down, strung up, beaten, burned and shot. Their white neighbors had turned on them with a viciousness that was gratuitous and grotesque — a cruelty too extravagant to be understood as a matter of mere survival. “It was not that the white American worker was threatened with starvation,” Du Bois wrote, pointing to the booming wartime economy, “but it was what was, after all, a more important question — whether or not he should lose his front-room and Victrola and even the dream of a Ford car.”

The East St. Louis Massacre of 1917 features in “The Broken Heart of America,” a new book by Walter Johnson, as one particularly horrific example of how St. Louis figures into the entwined history of white supremacy, capitalism and violence in the United States. Johnson begins with the Lewis and Clark expedition of the early 19th century and ends with the police shooting of an unarmed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014.

A professor at Harvard and the author of two previous books about slavery, Johnson allows that he has a personal interest in the subject — not as a victim of racial capitalism but as an unwitting beneficiary of it. He grew up two hours west of St. Louis, in a white suburb where people talked about “high property values” and “good schools,” and tried to distance themselves from the overt racism of their neighbors by deeming it unseemly. That gave them an “alibi,” he writes, for failing to recognize how their own privileged lives were built on exclusion.

I’m using the word “built” advisedly: One of Johnson’s arguments is that racism and inequality don’t just course through the city’s history but were built into its architecture and even its physical landscape. Located at the juncture of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, St. Louis was where the Southern system of slavery met the push for western expansion. The city functioned as the administrative center for the policy that became known as Indian Removal; with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, it became one of the northernmost outposts of slavery in the Union. The 20th century brought redlining and the destruction of black neighborhoods. The embodiment of the city’s “urban renewal” policies of the ’50s and ’60s was the enormous Pruitt-Igoe housing project, neglected to the point of utter disrepair before it was dynamited into rubble.

“The story of the human geography of St. Louis is as much a story of ‘black removal,’” Johnson writes, drawing a direct connection with the removal of Native Americans the century before, “as of white flight.”

When it comes to the history of racism and exclusion in the United States, St. Louis wasn’t unique in this regard; what it was, Johnson says, was more extreme. For a chapter on the 1904 World’s Fair that was held there, he has chosen the title “The Babylon of the New World”; the phrase originated from a Gilded Age civic booster who meant it as a compliment, equating St. Louis with an imperial center for culture and learning, but Johnson prefers the more ignominious connotations from the Old Testament — a city that presented itself “in the splendor of its boundless ambition, but rotten at the core.”

Johnson is a spirited and skillful rhetorician, juggling a profusion of historical facts while never allowing the flame of his anger to dim. Sometimes his metaphors can get a little overheated; after describing how the city of Ferguson levies outrageous fines on its poorest citizens, effectively harvesting them for operating expenses, he doesn’t really need to compare another form of revenue extraction to “a junkie using his kids’ lunch money to fund a bad habit.” He also errs on the side of rolling, multiclausal explications where a sharper indictment might sometimes do. But the story he’s telling has so many elements that it makes sense he would immerse himself in the intricacies of tax increment financing and municipal bond debt. As he ably shows, so much exploitation lies in the details.

In “The Broken Heart of America,” St. Louis emerges as a place of firsts: one of the first recorded lynchings, in 1836; the first city to pass a residential segregation ordinance by popular referendum, in 1916. Dred Scott filed his original freedom suit in St. Louis, where he lived; it eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled against him, deciding that black men “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

But solidarity and resistance found a place in St. Louis too. During the Depression, black and white workers joined together for a series of “hunger marches” in the city. Around the same time, black women nutpickers initiated a walkout at Funsten Nuts, white women sorters joined them and together they forced the company to double their wages. Eight decades later, the shooting of Michael Brown touched off the Black Lives Matter movement.

Johnson’s epilogue begins with an alarming image: Just outside St. Louis, an underground trash fire is burning its way toward a landfill of buried nuclear waste. But he doesn’t leave it at that. Nine pages later, he counteracts it with another scene, this time of high school runners circling a track on the city’s Northside. For many of them, life at home is rough, but last year more than half the team qualified for the Junior Olympics. “They fly around in the fading light,” Johnson writes, “little kids taking impossibly long strides.”

Book author Walter Johnson is Winthrop Professor of History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. Born and raised in Columbia, Missouri, he is the author of Soul by Soul: Life Inside in the Antebellum Slave Market (1999) and River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Mississippi Valley's Cotton Kingdom (2013), both published by Harvard University Press. His autobiographical essay, “Guns in the Family,” was included in the 2019 edition of Best American Essays; it was originally published in the Boston Review, of which Johnson is a contributing editor. Johnson is a founding member of the Commonwealth Project, which brings together academics, artists, and activists in an effort to imagine, foster, and support revolutionary social change, beginning in St. Louis.

[Essayist Jennifer Szalai is the principal book reviewer for The New York Times. Formerly an editor at its Sunday Book Review section and an erstwhile senior editor at Harper’s Magazine who also had a stint on the op-ed page of The Times, Jennifer is a graduate of the University of Toronto, where she studied political science and peace and conflict studies, and the London School of Economics, where she received a master’s in international relations. Jennifer has taught journalism and criticism at Columbia and NYU. Her work has appeared in The Times Magazine, Harper’s, The Economist, New York magazine, Slate, The Nation, The New Statesman, The New Yorker online and The London Review of Books.]

Spread the word