In the summer of 1921, the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry welcomed its first cohort of students to participate in a radical educational experiment: an immersive, eight-week program for industrial working women to study economics at a liberal arts institution. Participants came from all over the United States and from countries as far away as Italy, Poland, and Russia. They worked in factories that ran the gamut of twentieth-century industry: garment, millinery, printing, tobacco, soap (the list went on — the summer program’s director, Hilda Worthington Smith, catalogued nearly fifty trades in her 1929 account of the school).

Though many students did not have a high school education, at Bryn Mawr, they wrote poetry and studied history and science, performed in plays and took swimming lessons. They were treated to guest lectures by well-known figures, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Eleanor Roosevelt. They learned astronomy, using the college’s telescopes to marvel at the stars that urban pollution typically obscured from view.

Emerging from the workers’ education movement and created following the passage of the 19th Amendment, Bryn Mawr was the first in a wave of summer schools designed to train effective labor advocates. The goal was to engage workers in the study of capital, labor, and power — and enrich their lives beyond the workplace. A century later, the Bryn Mawr Summer School still offers a model for democratic worker education that can build the capacities of working-class people.

Economics — the Bryn Mawr Way

The education at Bryn Mawr was grounded in the realities of working-class life. The curriculum analyzed the position of landlords and business owners over renters and workers, as well as exploring the role of trade unions and legislation in redistributing power. A sampling of topics from a public speaking course included “Housing Problems in New York City,” “Life of a Night Telephone Operator,” and “Prison Made Goods.” The women-only program allowed students to more candidly interrogate experiences of gender inequity in the workforce and even in the labor movement.

Bryn Mawr looked beyond the immediately economic, too. It deliberately fostered creative pursuits, such as music, theater, and writing (some of which was published in a volume entitled “The Workers Look at the Stars”). As one participant put it in The Women of Summer, a 1985 documentary featuring alumni interviews: “It was a time to learn how to relax. I know I needed it, and I know damn well some of the others needed it.” Students understood that there was a political dimension to leisure, and that a shorter workday would give them time to imagine different futures.

The flow of learning went two ways. As Professor Elizabeth Lyle Huberman observed, students “were overflowing with knowledge of a world I didn’t know but felt I should have because my grandfather was a fisherman and my grandmother was a factory worker.”

Bryn Mawr also pioneered an early form of occupational therapy, recognizing the importance of worker health to a higher quality of life. The program hired a medical professional who analyzed the motions each student used in her daily work, offering advice on how they could be performed to reduce strain on the body.

The curriculum itself was contentious. M. Carey Thomas, then president of Bryn Mawr College, had seized on the sympathies of well-off women to secure support for the program. However, Thomas’s desire to provide an “apolitical” liberal arts education did not sit easily among left-wingers keen to mobilize participants in the class struggle. In particular, union leader Rose Schneiderman, who helped found the summer school, pressed for a curriculum that emphasized class and organized labor. This tension between liberal academics and labor activists endured throughout the summer school’s existence.

Students channeled their experiences of low wages, long hours, and hazardous conditions into solidarity work. They fought for shorter working days and improved living quarters for Bryn Mawr housekeeping staff, participated in local strikes, and spoke about the effects of unemployment at the Women’s Trade Union League conference. “I thought economics was something up in the clouds,” one participant remarked. “But now I see I’ve been living economics every day and didn’t know it.”

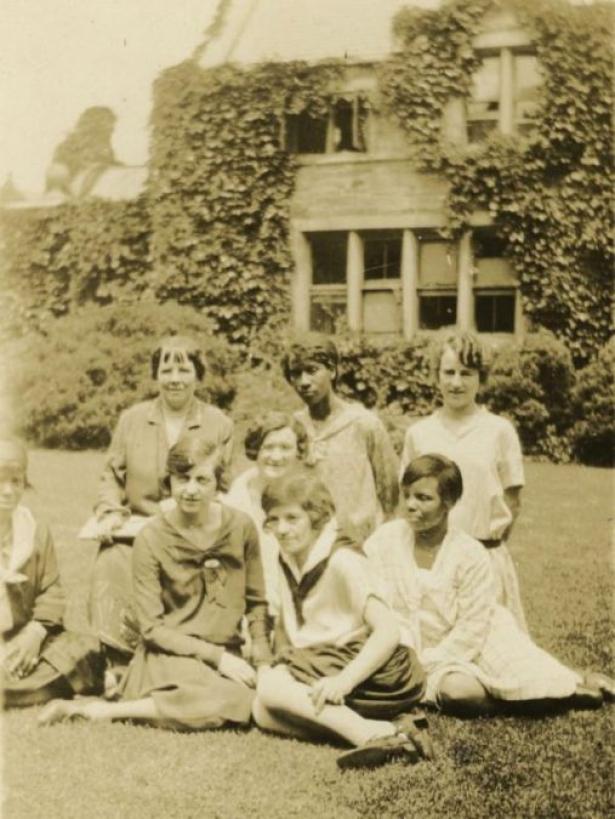

Participants also pressured the school to admit black women. M. Carey Thomas resisted, claiming it was inadvisable to “mix reforms.” But in 1926, Hilda Worthington Smith invited five black women to the summer school (eighteen years before Bryn Mawr College did so), and African American students continued to enroll in the program in the years that followed.

It took even longer for domestic workers. They were finally admitted on a trial basis starting in 1937. One domestic worker, Irene Rhones, wrote in the student magazine Shop and School that she and others formed a discussion group, meeting four afternoons a week to consider how organizing, standards, and legislation could benefit them. Rhones felt after that first year that they had built solidarity with the industrial workers and earned a place at future Bryn Mawr summers.

The Education and the Professors

Until the late nineteenth century, economics was typically taught in moral philosophy courses. Adam Smith had famously written on The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and scholars worked to place economics in social and historical context (the object of study was “political economy”).

In time, economists sought to distance themselves from ethics, politics, and social reform and portray themselves as objective, politically neutral experts. They increasingly emphasized mathematics and modeling, downplaying qualitative research and class conflict.

Things were different at Bryn Mawr. Many economics professors had dedicated their careers to advancing the labor movement, and many were women. (As of 2017, a mere 14 percent of full-time professors in the top twenty US economics departments were women.) Katherine Pollak Ellickson was a labor economist who worked for the Congress of Industrial Organizations and the National Labor Relations Board. Theresa Wolfson researched barriers facing women in the workforce and gender discrimination in trade unions. Amy Hewes helped pass the United States’ first minimum wage law in Massachusetts in 1912. At Bryn Mawr, she taught the advanced economics class, guiding students in conducting statistical studies.

The pedagogy and professors had a concrete effect: many students went on to become labor organizers. One was Rose Pesotta. Born in Ukraine in 1896 to a family of grain merchants, she moved to the United States in 1913. In New York, she worked in shirtwaist factories and joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU). Attending Bryn Mawr in 1922 deepened her belief that union members could benefit from studying under the guidance of knowledgeable instructors. In 1934, Pesotta was elected vice president of the ILGWU. She drew on her ties to Bryn Mawr by requesting Hilda Worthington Smith’s help to secure funding for workers’ education in Puerto Rico.

The ongoing conflict between working-class interests and wealthy Bryn Mawr donors and trustees came to a head in 1934, when several faculty members participated in an agricultural workers’ strike. This time, the protests garnered negative media attention, and funders pulled support, leading to a fallout between the summer school and Bryn Mawr College.

Four years later, the program ultimately closed its doors, less than twenty years after it began.

Worker Education Lives On

The story of the Bryn Mawr Summer School invites us to reimagine what an education to equip workers with knowledge and skills to advance their interests could look like. Core to the program was the exchange of ideas between students and educators, crossing class boundaries and upsetting hierarchies of power. While it took time for some professors to adapt, the emphasis on mutual learning modeled an approach to egalitarian democratic engagement that the founders hoped to foster in society at large.

In immersing participants in a world away from work and familial responsibilities, the summer school enabled students — at least temporarily — to experience time on new terms. Geared toward nurturing the whole person, Bryn Mawr united participants over their shared experiences as workers, but also as activists, as learners, as writers, and as women. No longer isolated in their various workplaces, they began to view themselves as part of a collective capable of collective action.

And there are existing resources they could draw on. Rethinking Economics, a network of students, collaborates with professors to develop curricula, textbooks, and workshops that feature heterodox economic ideas. Summer schools like the Summer Academy for Pluralist Economics and the Center for Popular Economics’ Summer Institute focus on economics for social and environmental justice.

To make a Bryn Mawr for today would require time, job security for participants, and money. Some might be unwilling to invest in a program that could be viewed as a “nice-to-have” luxury. But the women of Bryn Mawr showed that opportunities to create, think, and grow as part of a community are, in fact, essential to workers. If we want to create an economy where people are valued for more than their labor, worker education has a vital role to play.

Jackie Brown is a researcher, writer, and urban planner focused on economic justice and community-led initiatives. Leanna Katz is a lawyer interested in possibilities for work and welfare.

If you liked this article from Jacobin, please subscribe or donate.

Spread the word