In one of his interviews before the Taliban retook Afghanistan, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, blamed the American failure in Afghanistan on a change in Washington’s mission from anti-terrorism to “nation building.” In his view, Washington should just have held strategic sites in the country to keep terrorists off balance and not engaged in an ambitious reconstruction of Afghan society.

Bolton, one of the hardline conservatives who served as a high level official in the George W. Bush administration that invaded Afghanistan in response to 9/11, was engaging in what Americans call “Monday morning quarterbacking,” or declaiming in all-knowing fashion what “ought” to have been done. But it was all wishful thinking.

Like all other imperial powers, the US could not just wreck a society and engage in a purely military occupation of Afghanistan. Like all of them, it had to reconstruct a society, if only to reduce the costs of military occupation and give its venture a patina of legitimacy among both Afghans and Americans. And, like all, it could not help but attempt to reconstruct a society in its own image, even if the result was in reality a disfigured or distorted copy of itself.

In the case of the United States, reconstructing Afghanistan and later Iraq in its own image meant trying to create an avatar of American liberal democracy. The term for this process given by American policy makers was “nation-building.” However, a more accurate term to describe the American way of politically managing conquered societies is “liberal democratic reconstruction.”

The Philippines as Paradigm

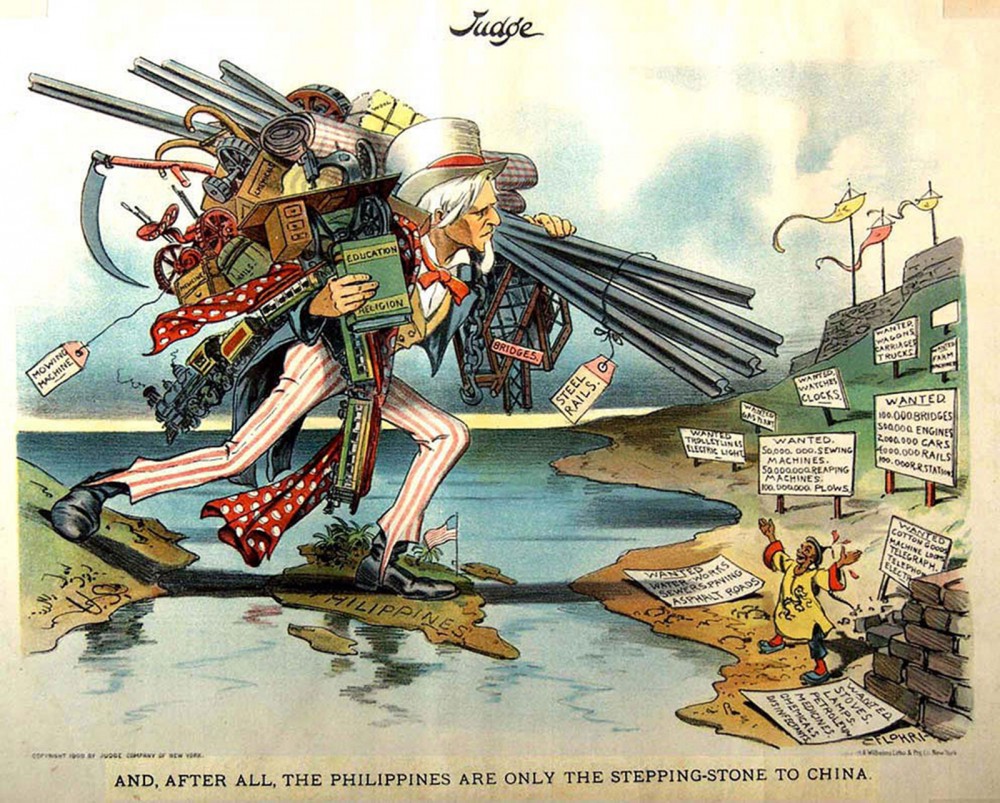

A Cartoon Uncle Sam carrying weapons, books, and supplies strides toward the Philippines, circa 1900. (Wikimedia commons)

The American experiment in liberal democratic reconstruction dates back not to Vietnam in the mid-20th century but to the U.S. conquest of the Philippines in the last years of the 19th century. As in the case of Afghanistan, it was an afterthought following a brutal suppression of a nationalist movement, which in this case took the lives of an estimated 500,000 Filipinos.

Liberal democratic reconstruction had two objectives: 1) To justify to the people at home an operation that had been undertaken to expand American naval power and acquire a strategic archipelago off the Asian mainland in order to corner the China trade. And 2) to come up with a solution for how to manage a conquered people.

Ironically, to legitimize a colonial war of conquest, Washington came up with a rationale that reflected America’s origins in an anti-colonial, pro-democratic revolution: “to prepare Filipinos for democratic self-rule.” The contradiction was not lost on many Americans, including the writer Mark Twain, but they were overwhelmed by the outburst of nationalist mass hysteria celebrating the U.S. joining the ranks of colonial powers.

The U.S. succeeded in the liberal democratic reconstruction of the Philippines. But that success was predicated on two necessary conditions: total victory over the resistance and the cooptation and cooperation of credible local elites in the creation of the liberal democratic order.

The wholesale transplantation of formal political institutions began shortly after the conquest. American colonial authorities and Protestant missionaries served as instructors, and an indigenous upper class constituted a dutiful student body. By the time the country was granted formal independence in 1946, the Philippine political system was a mirror image of the American one, with a presidency balanced by an independent Congress and judiciary. A two-party system emerged in the next few years.

On the ground, however, reality belied democratic ideology. Formal democratic institutions became a convenient cloak for the continuing rule of feudal paternalism in the highly stratified agrarian society the Americans inherited from the Spanish empire.

Wealthy landowners, those whom the United States had detached from the national liberation struggle and formed into a ruling class, enthusiastically embraced electoral politics. But it was hardly a belief in representative government that turned the local elites into eager students. The reason they so easily adapted to the U.S. system of governance was that it allowed competition for power among themselves via elections at the same time that it united them as a ruling caste over the unorganized rural and urban lower classes.

Reconstructing Defeated Japan

The next U.S. experience in liberal democratic reconstruction took place in Japan in the aftermath of the latter’s total defeat in the Second World War.

In describing the American post-invasion effort in Afghanistan and Iraq, officials of the George W. Bush administration compared their political project to the post-World War II reconstruction of Japan by the United States under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur.

Noted Japan scholars like John Dower and Chalmers Johnson dissented, however, pointing out that there were conditions in Japan that were not present in Afghanistan and Iraq. Indeed, Japan was more like the Philippines in terms of possessing the two necessary conditions for the success of liberal democratic reconstruction: total defeat of the subject nation in war and cooptation and cooperation of the ruling elite with the occupying power.

A summary of a major talk given by Dower at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2005, two years after the invasion of Iraq, laid down these and other preconditions of liberal democratic reconstruction’s “success” in Japan that were not present in Baghdad:

— “Legitimacy of occupation. A formal war was followed by a decisive defeat and unconditional surrender. U.S. allies also saw the occupation as legitimate. Serious planning for the occupation of Japan began in 1942.

— “Consistency. Japan had an intact government. Emperor Hirohito declared war, surrendered, and continued as head of state until 1971.”

— “Cohesion. While politically diverse, Japan was socially cohesive, without…religious, ethnic, and cultural conflicts.”

— “Security. Japan, an island, faced no domestic security issues. The hardships were staggering. But there was no terror.”

– “Exhaustion. Japan was at war from 1931 to 1945, leaving 3 million dead, 10-15 million people homeless, rampant unemployment, malnutrition, and disease. Defeat brought liberation from death. Suddenly, the air raids stopped. They could start over.”

From Afterthought to Mission in Vietnam

(Shutterstock)

Liberal democratic reconstruction’s successes in the Philippines and Japan, coupled with turning a blind eye to what made them unique — the total defeat of the resistance and the cooptation of credible local elites into the liberal democratic project — were probably what accounted for its elaboration from an afterthought to military conquest into a full blown missionary doctrine to counter communist-led national liberation movements during the Cold War.

Competition with communism led to a fateful modification of Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “Our revolution and its consequences will ameliorate the condition of man over a great portion of the globe.” Jefferson was thinking of America as an example.

But as Frances Fitzgerald pointed out in her acclaimed book Fire in the Lake, Jefferson’s conviction was transformed in the 1950s and 1960s into the creed that “the mission of the United States was to build democracy around the world… Among certain circles it was more or less assumed that democracy, that is, electoral democracy combined with private ownership and civil liberties, was what the United States had to offer the Third World. Democracy provided not only the basis for opposition to Communism but the practical method to make sure that opposition worked.”

Liberal democratic reconstruction was turned from an afterthought to manage a conquered population into a universalistic ideology that sought to remake the developing world in America’s image.

Vietnam provided a rude shock to America’s ideology of missionary democracy. American empire builders learned the hard way the three conditions that made Vietnam different from the Philippines and Japan. One was a national liberation movement that could not be defeated politically and militarily. Two, the local elites the U.S. allied with to build liberal democracy, like Bao Dai Ngo Dinh Diem, were neither liberal nor democratic and had been discredited among the masses by their having supported or tolerated French colonialism. Three, the U.S. was seen by a people that had successfully expelled the French as stepping into the shoes of the latter.

The Republic of Vietnam was an ersatz state whose writ only extended to big cities like Saigon, while the countryside belonged to the communists. There was little doubt among the Americans that that state would collapse once the U.S. left. The unwritten goal of the 1973 Paris Peace Accord was to give the U.S. a decent interval for an “honorable exit” before the communists took over the whole country. The North Vietnamese were, in fact, generous, giving the Americans over two years to return home before undertaking their final offensive in mid-March 1975.

The debacle in Vietnam was so shattering that liberal democratic nation building should have been buried there and then. Despite the efforts of a few right-wing historians like Max Boot to rewrite history to show that the American model could have succeeded there had the U.S. persevered in devoting the resources to nation-building, the consensus is that the raw materials for a successful transplant of the U.S. model were simply not there.

A New Lease on Life: Nation Building in Iraq and Afghanistan

Village elders greet Afghanaid representatives in Nechem, Afghanistan, 2010. (Shutterstock)

The ideology of liberal democratic reconstruction had been merely shelved, not buried. It received a new lease on life in the early 2000s, after the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. There were a number of factors that went into the invasions of both countries, including vengeance for 9/11, but both countries were essentially seen as providing Washington opportunities to reshape the global political environment after the Cold War.

The proponents of this strategy were the so-called “neoconservatives” that took over Washington with the triumph of George W. Bush in the 2000 elections, whose main personages were Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary of defense. Osama bin Laden’s presence in Afghanistan provided the excuse for the invasion of that country, while the swaggering Saddam Hussein, whom Bush II was determined to link to September 11, presented the perfect reason for invading Iraq.

Afghanistan and Iraq were intended to be what the Romans called “exemplary wars” in the neoconservative playbook. They were the first step in a demarche that would eliminate so-called “rogue states,” compel greater loyalty from dependent governments or supplant them with more reliable allies, and put strategic competitors like China on notice that they should not even think of vying with the United States. The willingness to use force in Iraq and Afghanistan was designed to make future applications of force unnecessary owing to the fear they would engender in friend and foe alike. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s offered the neoconservatives the opportunity to make permanent a unipolar world and they were determined to take it.

The Vietnam debacle was forgotten and liberal democratic reconstruction was taken from the shelf and dusted off as the political project that would immediately follow the invasion. For the neocon Max Boot, U.S. leadership of the unipolar world was all about “imposing the rule of law, property rights, free speech and other guarantees, at gunpoint if need be.” Military power would go hand in hand with political reconstruction to achieve “democratic transformation,” said another neoconservative thinker, Philip Bobbitt. “Or it might be called ‘liberal imperialism.’ What is wrong with that idea?”

Despite the hoopla about liberal democratic reconstruction, it never got off the ground in Iraq. Following the invasion, the U.S. flew in Iraqi exiles from the West to lead the effort, only to find out that these long absent members of the political elite had no base within the country. Then followed a massive insurgency led by former members of Saddam’s army that dispelled any illusions that Iraq was a defeated society, a “clean slate” on which a liberal democratic regime could be built. Then, taking advantage of the ousting of Saddam by the Americans, the long-marginalized Shiite majority utilized the electoral processes Washington promoted to set up an illiberal sectarian government that made the formerly ruling Sunnis second-class citizens.

Unable to stop the insurgency, the Americans made a deal with Sunni clan chieftains in the rural areas for them to use blood ties to bring the insurgents under control. But the aim of this arrangement, dubbed “counterinsurgency” and associated with Gen David Petraeus, was to allow U.S. troops to depart with the fiction of having stabilized Iraq. The dream of a liberal democratic Iraq was in shambles, and the chaos, instability, and power vacuum created by the invasion provided the opening for the Islamic State or ISIS that was eventually to take over wide swathes of the country.

Liberal reconstruction was even more of a botched up job in Afghanistan. The Taliban were not defeated, a precondition for a successful reconstruction. They simply yielded the cities but remained in control of the countryside. Nor were there credible local elites that would serve as reliable partners of the liberal democratic project. The regime that Washington tried to pass off as a democracy was really a deal among discredited, drug-dealing warlords based in fortified cities that had no traction beyond the city gates.

According to Richard Clarke, the top anti-terrorism official of the G.W. Bush administration, Washington’s handpicked head of state, Hamid Karzai, didn’t really have authority outside Kabul and two or three other cities. The U.S. ended up with an unworkable arrangement uniting the weak central government it had set up in Kabul and powerful independent warlords who engaged in extortion and drug dealing. For the latter, “insecurity,” as then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan put it, was a “business” and extortion “a way of life.”

Despite U.S.-sponsored elections, Annan predicted as early as 2004 that, “without functional state institutions able to serve the basic needs of the population throughout the country, the authority and legitimacy of the government will be short-lived.” The U.S., in other words, substituted a failed state for a Taliban state that, for all its problems and sins in the eyes of the West, had worked.

As for the Taliban, they simply provided a parallel regime in much of the country that performed basic governmental functions such as dispensing justice. A leading women’s rights activist contrasted the effectiveness of Taliban rule with the U.S.-sponsored regime’s performance: “In the more remote provinces, in cases of theft or similar minor crimes, the Taliban’s justice system could act more effectively than the local police. While I am not supporting the Taliban’s practices, their so-called courts led by their elders would hold hearings to find the violator, and then force the thief to return the stolen goods, outcomes that were not possible with a corrupt local police force that was receptive to bribes because of poverty and other problems.”

Life for women was certainly better in the cities, but promotion of women’s rights suffered from the same problem as the rest of the paraphernalia of liberal democracy: To many Afghans it had the stigma of being associated with the invasion. As Rafia Zakaria pointed out, “both within and outside the U.S. government, the white feminists decided that war and occupation were essential to freeing Afghan women…The enduring logic was that if they thought military intervention was a good thing, then Afghan women would too.” The problem was “Afghan feminists never asked for Meryl Streep’s help — let alone U.S. air strikes.”

To a lot of people, the Taliban, for all their hostility to liberal democratic rights and practices, represented rough justice and security for life, limb, and property; the Kabul government, in contrast, stood for hopeless corruption. So with their prestige and firepower, the Taliban knew it was just a question of biding their time. And they could afford to play the long game while Washington could not, owing to the unpopularity of the so-called called “forever wars” in the United States. Like the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, the peace deal to withdraw all U.S. troops by May 1, 2021, signed by the Trump administration and the Taliban, was designed to provide a figleaf of a decent interval for the U.S. to leave “with honor” before the Taliban took over the country.

What probably surprised even the Taliban was the swiftness with which the ersatz regime simply gave up as the U.S. withdrawal got going in earnest. Contrary to the western press’ image of a “brutal offensive,” the Talibans’ retaking of the big cities was largely a peaceful walkover with just a handful of casualties on both sides.

The amazingly rapid collapse of the government Washington had propped up for 20 years created precisely the image the Trump-Taliban deal had been designed to avoid: that of Americans frantically hightailing it from the country, leaving hundreds of thousands of their Afghan allies and their families behind. It was not the Taliban but the U.S.-sponsored failed state that did not give the Americans the decent interval that would allow them to leave with honor.

End of the Line?

Nation-building in Afghanistan and Iraq was the resurrection of a doctrine that had been discredited in Vietnam.

It should have remained buried, but it was dredged up to provide a justification for the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and serve as a handbook for reconstituting the state following military victory in the Bush administration’s drive to reshape the global political environment in a unipolar direction. But lacking the preconditions for success present in the Philippines and Japan, the venture collapsed in Iraq and Afghanistan in much the same way it did in Vietnam.

Hopefully, this time around, nation-building or liberal democratic reconstruction will be buried once and for all.

Foreign Policy In Focus columnist Walden Bello is senior analyst at Focus on the Global South and International Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton and the author or co-author of 25 books, including Dilemmas of Domination: The Unmaking of the American Empire (New York: Henry Holt, 2005).

Foreign Policy in Focus (FPIF) is a “Think Tank Without Walls” connecting the research and action of scholars, advocates, and activists seeking to make the United States a more responsible global partner. It is a project of the Institute for Policy Studies. FPIF is edited by Peter Certo, the senior editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies. It is directed by John Feffer, an IPS associate fellow, playwright, and widely published expert on a broad array of foreign policy subjects. FPIF is supported entirely by general support from the Institute for Policy Studies and by contributions from readers. If you value this unique resource, please make a one-time or — better yet! — recurring contribution to help us keep publishing.

Spread the word