Dave Helminski will drop off his last package for United Parcel Service Inc. on Christmas Eve 2022 and retire after four decades as a driver in Chicago. He joined UPS after four years in the Marine Corps and a yearlong stint installing carpet. He put in a few years loading trucks, then became a driver and was set for life. After Helminski drops off that last package, he’ll have pensions that provide almost the same $100,000 a year he makes now. “I came out of the lower middle class, and I’m living the dream,” Helminski says, wearing a face covering with the Marines emblem as he heads home from his shift at a large UPS facility in the northern suburb of Palatine.

Helminski’s dream industry has lately become more of a nightmare scenario at rival FedEx Corp. The massive labor shortage that’s rocked the U.S. since the pandemic and disrupted long-established employment relationships hasn’t had much impact on UPS, which pays its unionized drivers the highest wages in the industry. That’s helped it maintain a stable workforce and rising profits throughout the current disruptions. Meanwhile, lower-paying, nonunionized FedEx racked up $450 million in extra costs because of labor shortages. And while UPS easily beat earnings expectations and predicted a rising profit margin in the U.S. for the fourth quarter, FedEx signaled that its profit margin will fall further. The lack of workers is taking a toll on its reliability, too. FedEx’s recent on-time performance for express and ground packages has sunk to 85%, while UPS has met deadlines on 95% of those packages, according to data collected by ShipMatrix Inc.

With strong package demand and delivery prices jumping more than 10%, FedEx’s struggles have left investors puzzled, says Amit Mehrotra, an analyst at Deutsche Bank. The company’s travails have laid bare some structural inefficiencies in its business model, too. Unlike UPS, FedEx operates two distinct delivery networks: one for its overnight air delivery business, which is handled by FedEx employees, and another for its ground parcel service, which uses independent contractors to make final-mile deliveries employing their own nonunion drivers.

Refined by FedEx founder Fred Smith, the model was supposed to benefit the company by pushing variable labor costs and the expense of vehicles to the contractors that operate local routes. And it worked well in a market dominated by commercial packages, Mehrotra says. But the ground parcel business has expanded rapidly with the growth of e-commerce in the past decade, resulting in far more residential deliveries. Such home service requires the contractors handling those deliveries for FedEx to drive more miles between stops and leave fewer packages at each location, boosting costs. When the pandemic hit, residential deliveries exploded, forcing contractors to hire more drivers and FedEx to add more package handlers. “There’s definitely been a loss of confidence in this business” among FedEx investors, Mehrotra says. “There’s something wrong.”

FedEx defended its contractor model as innovative, highly flexible, and scalable, said spokesman Perry Colosimo in an e-mailed statement. The model “has been instrumental in helping us navigate a difficult environment and will continue to play an essential role in positioning our business for long-term success,” the statement said.

Investors have long pushed FedEx to combine its express and ground networks. Smith agreed to acquire the ground network at an opportune time in 1997, less than two months after a 15-day union strike ended at UPS. His use of contractors allowed FedEx to expand the business quickly without the expense of buying vehicles or managing drivers. FedEx Ground became the growth engine for the company and posted profit margins in the midteens.

But the pandemic led many U.S. workers to question whether jobs with low wages and challenging work conditions were worth returning to. FedEx, Amazon.com Inc., and other companies that pay their operational employees wages and benefits lower than those received by many unionized workers are struggling to hire people even though they’re now raising salaries. FedEx Ground has seen average wages for workers in its sorting facilities jump 16% from a year earlier.

FedEx has warned that its labor problems will persist into this quarter, and analysts predict the ground unit’s operating margin will sink to 6.8%, from 7.5% a year earlier. Analysts expect UPS’s fourth-quarter profit margin for its U.S. domestic business will rise to 9.9%, from 8.8% a year earlier.

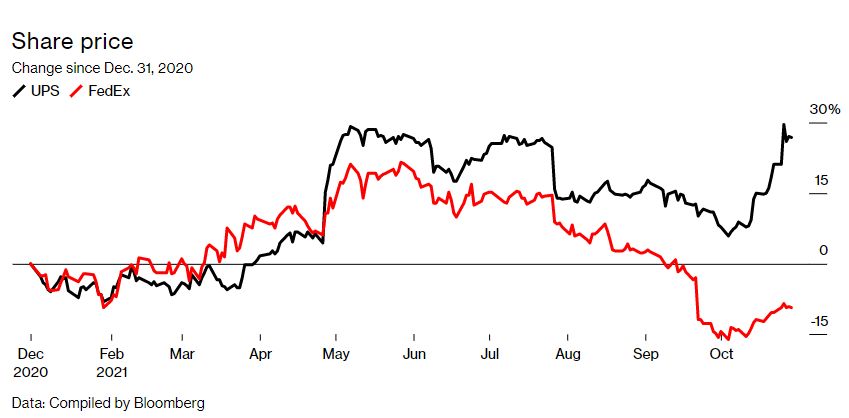

The difference in performance predates the worker shortage. Even while paying union workers almost twice what FedEx Ground drivers make, UPS earns a return on invested capital that’s more than double its rival’s. In the last full year, UPS and FedEx each had sales of about $84 billion; UPS banked $7.7 billion of operating income, while FedEx earned $5.9 billion. Investors have taken note: UPS shares have risen 27% this year; FedEx’s have dropped 9%.

Smith defends operating the two networks despite inefficiencies, including when FedEx Express drivers on company payroll take an overnight package to the same location where a ground parcel is dropped off by contractor drivers. Yet, while Smith has been able to hold union organizers at bay by relying on contractors, FedEx Ground’s savings on labor lately hasn’t filtered down to the bottom line. That’s because its 5,600 contractors are mom and pop outfits, many with fewer than 10 employees. They face the same elevated costs inherent to small businesses. They pay full price for vehicles, tires, oil, parts, maintenance, and other items that UPS buys at scale. Each contractor has the same back-office work and often farms it out to third parties, adding to expenses.

FedEx Ground keeps contractors small by design to avoid becoming too dependent on one company in a service area. That lowers the risk when contractors fail, which isn’t uncommon. FedEx Ground can call on other contractors to plug the hole in service, paying them extra per package to entice them to send teams to the area.

Contractors spend a lot of their time recruiting drivers—turnover ranges from 30% to 60% of the workforce each year. In some cases, they poach drivers from other FedEx contractors. UPS’s richer pay package makes it easier for the company to hire part-time workers at the sorting hubs, where it also offers the incentive of moving into a delivery driver job that can eventually pay, as in Helminski’s case, almost $100,000 a year, with overtime. This creates a stable workforce at the hub and a steady pool of driver candidates whose work habits are already known to the company.

FedEx’s sorting hub in Portland, Ore., is operating with only 65% of the staff needed. That forces the company to reroute packages to other facilities, incurring costs for the extra transportation and reducing the efficiency of the network, officials said on a September conference call with analysts. In total, FedEx says the ground unit is rerouting 600,000 packages a day because of labor issues.

UPS does have to worry about strikes during labor contract negotiations every five years. The current contract expires in 2023. For now, UPS and its workers are doing well, says Helminski. “We’re making a good living,” he says. “We’re the gold standard.”

Thomas Black is a Bloomberg News industrial reporter.

Spread the word