EZRA KLEIN: I’m Ezra Klein. This is “The Ezra Klein Show.”

So before we begin today, a bit of job creation. We are looking for a researcher on the show. This job is exactly what it sounds like, somebody who’s going to work with us on researching the guests, the episodes, the work, help write questions, help shepherd the episodes through. But this is the central thing that makes a show go. If that sounds like you, sounds like your skill set, sounds like something you want to be doing, have done, can show us that you’d be amazing at doing it and that you really get the show on a deep level, we have put the link to the job description in the show notes.

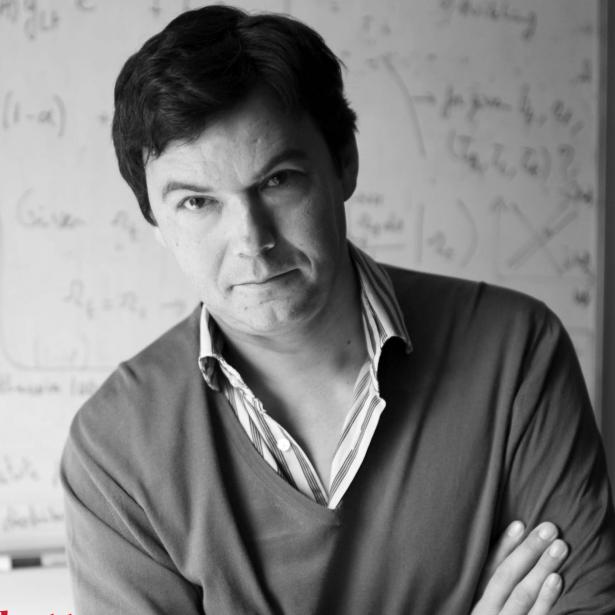

But for today’s episode, Thomas Piketty — finally, Thomas Piketty, I think one of our most requested guests. If you don’t know Piketty, he’s arguably the world’s greatest chronicler of economic inequality. Across a series of papers now, working with a wide range of co-authors, he’s put together these painstaking cross-national data sets, showing the extraordinary amount of income and wealth that has flowed to the top 1, and even 0.1, and even 0.01 percent of the population.

His book detailing the way capitalism rewards wealth over work, detailing why those trends actually happen, “Capital in the 21st Century,” was a huge international bestseller, which was a real rarity for a book like it. It’s a long, dense, complicated work of economics. But Piketty is one of those people who, through empirical work, through theory, has genuinely reshaped the way we think about central dynamics of the economy. He’s really a transformational intellectual figure.

And he’s got more to say. His new book, “A Brief History of Equality,” isn’t just detailing our continued descent into economic dystopia. It’s a book that is much more optimistic about our past than people associate with him. He argues that we’ve seen a march towards equality that many of us still underrate. And then it’s much more optimistic about the future we could have, because Piketty thinks that we can have much more radical policies than most economists or politicians buy into, that could really build a far more equal world. I mean, we’re talking here a universal minimum inheritance of around $150,000 per person, worker control over the boards of corporations, massive levels of wealth taxation. He’s really putting forward solutions proportionate to the size of the inequality problem. And so it’s bracing stuff to read.

Piketty, I should note, is French. His English is so much better than my French. But if there’s anything here you have trouble understanding, we will have a transcript up at The New York Times a couple of hours after the show comes out. As always, my email, ezrakleinshow@nytimes.com.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Thomas Piketty, welcome to the show.

THOMAS PIKETTY: Thanks for inviting me.

EZRA KLEIN: So I’m thrilled to have you here. I think you’re arguably the world’s leading chronicler of economic inequality. And so, what then led you to write a book chronicling equality, a sort of more fundamentally optimistic work, I think, than many of your past pieces?

THOMAS PIKETTY: You know, I’ve always viewed my work and conclusion as relatively optimistic. And I was a bit sad to see that some people had a different reading. So I thought it was time to reframe everything, to clarify maybe some of my thinking. One of the problems that my past two books, “Capital in the 21st Century,” and “Capital and Ideology,” were really long. And so people can get lost into the argument. And I really wanted to write a much shorter book.

And by doing that, I think maybe I was able to clarify my thinking. And also, maybe to clarify the fact that, yes, in the long run, there is a movement toward more equality. So when I talk about the long run, I’m looking at the two centuries — two centuries and around starting at the end of the 18th century, with the French Revolution, the U.S. revolution, to some extent. And I look at the broad evolution of political equality, social equality, economic inequality over this period. And yes, I see a long-run movement toward more equality, that did not come naturally or smoothly. It came out of major political mobilization, social struggles in some cases, sometimes major crises.

But in the end, this is the construction of new institution, of new legal, educational, fiscal, social rules of the game, that have transformed our societies in, I would say, a very positive manner, that have made them both more equal and more prosperous. And this is the story I wanted to focus upon. Because I think in the end, this is a major lesson from all this body of historical sources and data that I have been gathering for a number of years now.

EZRA KLEIN: Let’s work through the argument of this book. And an important move you make, right at the start, is, particularly in America when we think about inequality, we tend to focus on income statistics. And you argue that wealth inequality is the more important measure to focus on. Why?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Well, I think wealth is, in a way, a better indicator of opportunity, of power than income. And more generally, what I care about is really the equality or inequality of capabilities as Amartya Sen would have said. So what you can do with your life, the kind of choice you can make, the bargaining power you have, vis-à-vis the rest of society and vis-à-vis your own life. And from this viewpoint, wealth is quite important.

Because when you have no wealth at all, or even worse, when you have negative wealth, when you have only debt, you need to accept everything, basically. You need to accept any working condition, any wage. Because you need to pay for your rent, you need to take care of your family or relatives. And you cannot really make choices.Whereas, if you have just — even just $100,000, $200,000, or $300,000, or euros, this can seem very small to someone who has millions or billions, but in fact, this makes a big difference, as compared to having zero or negative wealth. Because then you can — so if you are being proposed a job and you don’t like it, you don’t need to accept it right away. You can wait a little bit. You can try to create your own business. You can build your own home so that you don’t need to bring in a wage and rent every month. And you can start different kinds of projects in your life.

So this puts you — it’s much more than money. It’s really a question of bargaining power with respect to the rest of society and basically deciding the kind of life you want to have. So it goes well beyond just economics, in a way. It’s much more important than that. And indeed, this movement toward more equality that I describe in the book is primarily a movement where more and more people acquire more and more control, agency, power, opportunity with respect to their own life.

And from this viewpoint, yes, wealth indeed is a better indicator than income. Generally speaking, we need to have a multidimensional approach to inequality and to the kind of social and economic indicators that can help us to monitor this long journey toward equality. So income is important, wealth is important, but there are many other indicators, including access to political participation, to participation to decision making in companies. And so we need this multidimensional approach. And I think I am also clearer in this book about this maybe than I was in my previous two books.

EZRA KLEIN: It’s something I really appreciate in your thought, the attention to power in all directions. That wealth is a form of power, bargaining power, vis-à-vis society, as you put it. That it is often gained through power. It is not an automatic story of economic policy or markets or technology. But you’re not just storytelling here, you’re also tracking data, and tracking data over a quite long period of time. You’re tracking wealth distribution across society, across multiple countries, over more than 200 years. What kind of data are you using for that? Why should I believe that the data we have on wealth in France or the U.K. or the U.S. from more than 150 years ago is good enough data to build the kind of story, and draw the kind of conclusions, and run the kind of analysis that you do?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Right, so I think the data we have on wealth and property for the late 18th century and the 19th century is probably better than what we have today. First, because at the time, you didn’t have tax havens, you didn’t have progressive taxation. So people did not have a strong incentive to try to hide their wealth. And in fact, it was quite the opposite. Wealth and property was very often at that time a way to establish your political rights. And indeed, you have a political system which are very often based on property in order to grant you voting rights.

So the data is pretty good. In a way, the problem with the data is more — today, where we need to make a lot of effort, try to use values, data sources in an imaginative manner, in order to make sure we can correct for all the tax evasion, for all the wealth and tax havens. We do our best to do that. We’ve made progress, but certainly there’s still a lot of progress to be made.

Sometimes we imagine we live today in a world of big data and big transparency, but in fact, some private companies accumulate a lot of big data, which sometimes we would like them not to accumulate on ourselves. But in terms of public statistics, and public information about who owns what and how this is changing over time, we actually live in an age of big opacity. And it takes a lot of energy to try to combine the relevant information for the recent period.

And this is the kind of work that historians started to do a long time ago. I should say, all my work is really in the continuation of a large body of historical research on income, and wealth, and wages, and prices, which started in the late 19th century. But for us, when I started working on this, in the late 1990s and in the post-2000 period, we’ve been able to process a much larger quantity of data, to increase drastically the number of countries.

And by having 10, 20, 50, 100 countries, rather than one of two, you can make comparisons. You can start asking, OK, what kind of impact did it have for this country to have a rise in inequality or a decline in inequality as compared to this other country. We’re still very uncertain about a lot of conclusion. Let me say, we are in the social sciences, we are not going to have a mathematical formula.

EZRA KLEIN: So when you track all this data, when you run the trends, in the U.S. and in France and the U.K., other parts of Europe, there’s obviously a lot that emerges. But what are the three things you feel you’ve learned from looking at these trends over time, that people might not expect? Once you’ve immersed yourself in the data, how does the story of equality change from maybe what our folk wisdom or intuitions about it would be over this multi-century time period?

THOMAS PIKETTY: OK, the three most striking conclusions, maybe, to me will be, first, there’s been a long-run movement toward more equality, both of income and wealth. And I’m going to be more specific about this in a minute. So go on, main finding, this movement toward more equality in terms of income and wealth really starts only after World War I and World War II, during the 1940-1945 period. There’s really not much going on in the 19th century and pretty much until World War I.

And three, the third finding is that this movement to have more equality, although it’s still there, if you compare the situation today with the situation in 1910, 1914, we live in a more equal world, in terms of equality of wealth, and especially equality of income. This movement has been of limited magnitude, in the terms of the concentration of wealth is still very large.

So let me maybe be a bit more specific about the numbers that people should have in mind, so that they can understand what I mean with these three findings. If you look at the distribution of wealth today in the United States or in Europe, what’s really striking is that the bottom 50 percent of the population basically owns almost nothing at all. So, what I mean — nothing at all, in the U.S. it’s going to be 2 percent of total wealth owned by the bottom 50 percent. In Europe, it’s going to be 4 percent, so that’s better than 2 percent, but it’s still very small.

The top 10 percent would own over 70 percent of total wealth in the US and around 60 percent in Europe. And so the rest will be owned by the 40 percent of the population that are in between the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent, by definition. So this illustrates my point number three, which is we still have a lot of inequality. This looks like a very large concentration of wealth. And indeed, if we are looking at income, it will look less extreme, much less extreme than this. The bottom 50 percent maybe would have 20 percent of total income, rather than 2 or 4 percent. So this is much less extreme for income than full wealth.

Now, although inequality of wealth today looks very large, one century ago it was even more extreme. So if you look at Europe in 1900 or 1910, the top 10 percent would own 90 percent of wealth, rather than 60 percent today. So that, in the end, this middle 40 percent who are in between the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent, at the time were almost as poor as the bottom 50 percent. They would own between 5 percent and 10 percent of total wealth. And the bottom 50 percent would own 1 percent or 2 percent. It’s as if you have no middle class in the sense that what middle class — it’s always a bit richer than the bottom 50 percent, but they really did not own much.

So there has been some significant improvement in the long run, in the sense that this middle 40 percent group, who used to be almost as poor, in terms of share of total wealth a century ago, now owns up to 40 percent, almost 40 percent of total wealth in Europe and bit less than 30 percent the US. So this is a significant improvement.

A striking fact, which I didn’t know before looking at the historical data, is that this movement, while limited diffusion of wealth to the benefit of this middle 40 percent, did not start really before World War I. So in the 19th century, and in the early 20th century, until 1914, you have more concentration of wealth or the stabilization at a very, very high level of wealth concentration, but the movement toward less inequality really starts after World War I, World War II, following large transformation of the social systems, the fiscal system, the rise of progressive taxation, the rise of Social Security. So some of this political movement, of course, started before World War I.

And it’s very difficult to rewrite history about what would have happened without World War I and World War II. You can certainly make the case that in the U.S., the Great Depression was an even bigger impact on the political landscape and social landscape than the war. You have countries like Sweden, which World War I, World War II did not have such big impact on, such a large importance as in other countries, and which still had this movement toward more equality, and to some extent, even more so than the others.

So I don’t mean to say it’s really the war itself. It’s more this entire process during the first half of the 20th century is going to lead to a transformation of the political, social and fiscal system in such a manner that this is going to lead to a limited diffusion of wealth and a limited rise of more equality.

EZRA KLEIN: Well, let me get to that emergence of a wealthy middle class. So, I think the story you tell there is incredibly striking, for a couple of reasons. One, of course, the punctuated nature of it. While we can’t know exactly how much of a driver war was — there’s another book about moments in time when inequality really changed, “The Great Leveler.” And I would say the takeaway of that book is the only force is stronger than those protecting great inequality of wealth are wars, plagues and total societal collapse. And it’s a pretty grim conclusion.

But I also find your story here surprisingly grim in a way. Because on the one hand, you’re telling a story of dramatically rising equality over a long period of time. But that story is actually really a story of change in inequality, wealth transfer, almost entirely among the top 50 percent of the income distribution. So the bottom 50 percent goes from — depending on the country, but roughly two points of the total wealth distribution in the 1800s, early 1800s, to around five today.

And I can then hear my conservative friends saying, well, doesn’t this suggest something is wrong with your data? If wealth is power, if this is a measure of inequality, would you really rather be in the top 10 percent in 1800 or the bottom 20 percent today? Is it really not true that the bottom 50 percent of the distribution has a lot of political power today, and just a lot of power they didn’t have in the early 1800s? So how do you respond to conservatives who say, this is actually missing how much the economic changes in this era over this period did to diffuse the fruits of economic growth, of technological change, of riches, such that the wealth distribution is obscuring more than it reveals.

THOMAS PIKETTY: Right, so what I would respond is that they should start reading chapter one of my book, and in particular Figure 1 and Figure 2, where I start by analyzing the fact that average income per capita has been multiplied by 10 over the past two centuries. So, that’s the first. Together, with the big rise — so Figure 1 is about the enormous rise in life expectancy and the enormous rise in literacy rates. And Figure 2 is about this enormous rise in income per capita.

And so this is, of course, the first way — you ask me about what was the most surprising finding. So this, I did not invent the big rise in per capita income or life expectancy. So that’s why I did not start with this. But in the book, this is, of course, where I start. Because this is the first way in which there’s been an enormous increase in opportunities, in power, in equality. So the fact that you can live your life until age 60, 70, 80, rather than dying at 20 or 30, is a major positive transformation. The same thing about access to culture and literacy. The same thing, to some extent, about access to purchasing power.

And the second thing in which I insist immediately at the beginning of my brief history of equality is that this historical rise of modern economic prosperity — and there is this multiplication by 10 of average income — came together with more equality, and in particular with more equality in education. So to summarize, the true source of economic prosperity is equality, or at least a relative equality in education. And a big part of this very large rise in purchasing power, which is one of the first form of the rise of power in general — this big rise in purchasing power happened in the 20th century, which is a time when you have big reduction of inequality. In some cases, very high progressive taxation.

So in the United States, the time when the United States has a maximum economic prosperity and maximum economic dominance over the rest of the world is also the time between 1930 and 1980, when the top income tax rate, as we know, on average was about 80 percent. It was some times 91 percent, sometimes 70 percent. On average, it was of the order of 80 percent.

Not only this did not damage American prosperity, but in fact, this was a period of time with the maximum U.S. prosperity with respect to the rest of the world, with the biggest gap in terms of productivity between the United States and the rest of the world. Why is it so? Because the US at the time was the educational leader. And you need to wait until the 1980s, ’90s, to get convergence of other Western countries on the U.S. educational level and also convergence in productivity level.

So the big lesson from history and from this big picture analysis is that the historical is a true source of increased prosperity, increased productivity, increased income and purchasing power, is the rise of education, and relative equality in education, in the sense that you want to have broad access to education. I mean, you don’t want to have everybody going exactly through the same education, but you want to have 100 percent of the population going to primary school and then 100 percent going to secondary school. You need this very broad access to education. And this has been the true source of prosperity.

So you see that this movement toward more equality is a movement that needs to be put into a perspective that is much broader than just the evolution of wealth, concentration and wealth shares during the 20th century, which is also important, but in a way, maybe it’s less important than first this big long-run rise in prosperity, and also the big long-run rise in political participation.

EZRA KLEIN: I want to get to political participation here, because I think it raises the very puzzling question from the other side. A conservative might look at this and say, how can you not track a rise in wealth, despite the fact that the lives of people at the 25th percentile are so much better today than in 1800? I think the way somebody more on the left, or certainly somebody who’s more liberal, who believes more deeply in democracy, might look at this, is to say there’s a puzzle here.

The longtime view, certainly the longtime fear of democracy was that if you give people the opportunity to vote, that 50 percent at the bottom of the distribution, that 50 percent, plus one — that 60 percent, which has so much less wealth than the top 10 percent, but so many more people, are just going to vote the wealth of the top 10 percent over to them. And ambitious politicians, who want to win votes in a system that more or less, not perfectly, but more or less runs on votes, is just going to go to those people and say, if you vote for me, I’m going to have a huge wealth tax and I’m going to take all these people’s wealth and I’m going to give it right to you.

And the fact that there is such unbelievable stability in the wealth distribution over this period, where these countries do become vastly more small-d democratic is really puzzling. It’s really very puzzling. Like, how did it not happen? How did this fear and this seemingly logical outcome not come to pass, that the bottom 55 percent didn’t vote themselves a much larger share of the top 10 percent’s wealth? How do you understand that?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Well, there are several explanations. The first factor I want to stress is that it took a long time to extend the right to vote. And even in the late 19th century, early 20th century, you still have lots of countries where the right to vote is very unequally distributed. So the first answer to your question is, well, in some countries, it took a long time to actually get equal voting rights.

The second answer is that equal voting rights is not enough. If you have very unequal funding of political campaigns, and typically, that’s one of the key problems you have in the U.S. today, but also, it was the same situation in countries, like in France, in 1900 or 1910, where you already have universal suffrage for men. So it was more advanced than Sweden in a certain manner. Or in Britain, there were several extension of the suffrage. It was still not universal in 1900 and 1910, but it was getting close.

But the problem is that in France and Britain, at the time, you still had very unequal power in terms of influence into the political process, financing political parties, campaign financing, the media. In the U.S., it was maybe less entrenched at the time than in Europe. I think it has become more entrenched today. So in a way, the U.S. becomes a new old Europe of the world and has a form of inequality today, which I think is close, in a way, to Europe, during the Belle Epoque period, which very entrenched economic elite and political system, where there’s a private financing of political campaigns and political action committee. Makes it really difficult to change the system, and particularly the economic and tax policy. I mean, I think things can still change through political mobilization, but this makes things more complicated.

And finally, the third reason why things are complicated is also because it’s not so obvious to determine for the majority of the voters what’s the right level of equality or inequality. I’m certainly not saying that full equality is the ideal, because you can have very good reason why different people want to conduct different lives, make different choices. You may want to have some incentives. So even if you don’t have this problem of unequal political right and unequal political influence, it’s a matter of learning over history about the right institutions, the right level of equality and inequality.

So just to take an example. Before very highly progressive taxation was experimented historically, in particular in the United States, between 1930 and 1980, it was difficult to know how it would work. And so the way I write about this today is very different from what people could have written in 1910 or 1920, before it was experimented, where people could say, this is going to be a disaster, this is going to destroy the economy.

Now, of course, some of these arguments were sort of self-serving argument. But partly, they were also plausible arguments. So I think there’s a process of large-scale experimentation and learning about the right institutions in history that is still going on, of course. And that is much more complex than simply, OK, the poor are going to expropriate the rich and et cetera.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

EZRA KLEIN: One thing about this book that I really appreciated about it is that it isn’t just a dry recitation of trends, but it is a proposal for a series of fairly transformative policies that I think is, as you see it, would bring liberalism closer to many of its long-term claims, that it does not tend to achieve. So tell me about what you call participatory socialism. What makes participatory socialism different from conventional social democracy?

THOMAS PIKETTY: In my view, this is really the continuation of social democracy into the 21st century. So what does the limits — there’s a great limitation of social democracy. I see three main limitations. One is that in terms of wealth concentration, there has been limited progress. So the bottom 50 percent today, in spite of the rise in incomes, or rise in the welfare state, of course, they have a much better life today than one century ago. That’s quite obvious in terms of access to education, to health, to pension, to income. That’s a huge progress.

But still, in terms of wealth, as we’ve said at the beginning, they own 2 percent of total wealth, 4 percent of the total wealth. So there’s been very limited progress. So how can we make progress in this direction? And what I argue in the book is that one way to move in this direction will be to have a minimum inheritance for all. So that’s not instead of Social Security, basic income, a free education, free health. This comes on the top of all of this. And this is maybe the final step or one of the final step in this long process.

So I give concrete example. I say, OK, maybe you want to have everybody at age 25 who should receive, say, 120,000 euros, which in the European context will be about 60 percent of average wealth, which is currently about 200,000 euros per adult. So in the U.S., maybe it will be a bit more, say, $150,000. I don’t know, something like this. I should say, we will still be very far from equality of opportunity, in the sense that the bottom 50 percent, who now receive close to zero, they would receive, say, 120,000 euros. People who are in the top 10 percent, who today receive an average about one million euro, will still receive 600,000 euros after the progressive tax on inheritance and wealth that’s paying for all of this. So you will still have substantial inequality of opportunity between these two broad groups.

And if you want my opinion, I think we could go much further away in this direction. But this will already make a big difference, because this will give more power and more opportunities for the bottom 50 percent. And I’m always very surprised by the fact that people often claim that they are in favor of equality of opportunity at a theoretical level and then when you propose concrete policies to move in this direction, many people, especially people from the top of the distribution, get completely crazy, and say, oh, what you’re going to give money to these poor children, that they’re going to do terrible things with the money, as if wealthy children always made good choices with the money they receive.

So if people want to put limits on what people could do with the minimum inheritance, I have no problem with this, as long as you put the same limits on all inheritors, including wealthy children. But otherwise, this looks like a very illiberal and authoritarian approach to opportunities in society.

EZRA KLEIN: A couple of places I want to dig into this policy, because I think it’s genuinely fascinating. And I could not agree with you more — it drives me crazy, the trope in American politics, where even conservatives will say, well, I don’t agree about equality of outcome, what I believe in is equality of opportunity. And equality of opportunity is unbelievably difficult to achieve and nobody’s even really trying.

I have a couple of questions about this policy. The idea that you could impose a wealth tax of sufficient size, that people who are wealthy now would not lose everything they have, but you could be giving every member of society around $200,000 in perpetuity, not just for a year or two, as you do the front end of that wealth tax, but in perpetuity, I think people are going to wonder about the math of that. Is that really true or is that a fantasy? So can you say a bit about why you’re confident the numbers of this net out, that you could make such a big guarantee to such a large population going forward without needing to do something — without doing something that would destroy the economy?

THOMAS PIKETTY: One way you could do it is you could just redistribute the flow of inheritance each year. So each year, the average inheritance that is transmitted to the new generation, it will be of the order of 200,000 euros in Europe, or $250,000 or $300,000 in the U.S. So you could just replace this by a lump-sum payment to everybody in the generation. And you did not — you don’t need to tax wealth, you just do it through the redistribution of inheritance. Now this is not the way —

EZRA KLEIN: So just to clarify that, so you’re saying that every year the amount of money that is passed on an inheritance in, say, the U.S., is so large that if you divided it by the denominator of all the people, I guess, who would turn 25 that year in the U.S., you would get — it’s like $250,000, $300,000 per person?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Yeah, because this is exactly the average wealth of decedents in the U.S. today. So on average, decedents leave $250,000 — $300,000 per individual decedent every year. So it means that on average, because families have about two children on average, every children is going to receive on average $250,000, $300,000. Now, this is an average.

Then if you look at the distribution, the bottom 50 percent of children actually receive close to zero. And the top 10 percent of top 1 percent are going to receive millions. But the average is about $250,000, $300,000. So you could just redistribute these equally and by definition, everybody will get this same amount. And by the way, you could have it at 25 for everybody instead of having some time at 15, some time at 45, sometimes at 60, depending on at what time people die, et cetera.

So that would be one way to do it. This is not the way I propose to do it. Because I think you actually want to let people leave different levels of inheritance for all sorts of good reason. And so, the way I propose to finance this minimum inheritance, which in my proposal will be closer to 120,000 euros or $150,000, which could be paid for by a tax of around 60 percent of all inheritance. But this is not the way I propose to do it. I propose to pay it partly by progressive tax on inheritance, but mostly by progressive tax on wealth.

Why is it so? Because I think, generally speaking, the progressive wealth tax is a better instrument than the progressive inheritance tax. Both are useful, but the progressive wealth tax is more useful because it allows you to adjust the contribution to public finance, to your current situation, basically. Life is long. Life has always been long, but life is particularly long today. So when you have a life expectancy of 80 or 90, if you make a large fortune at age 30 or 40, we are not going to wait until you are 80 or 90 before you contribute to the public finance of your country. So it’s much better to have an annual wealth tax to contribute to redistribution.

And so just to give you orders of magnitude. This minimum inheritance for all, if this is set at the level of 60 percent of average wealth, so everybody would receive, at age 25, 60 percent of average wealth, the total cost for our country will be of the order of 5 percent of national income each year, which is significant, of course. But as compared to a large modern welfare state, which in Europe will raise 40 percent to 50 percent of national income, this will only be a component of 5 percent of national income. So that’s significant, but it will be smaller, for instance, than the cost of a total health care system or total education system or pension system.

So it would just be an extra component to the social state or to the welfare state in general. But let me make very clear that this is not a component that is hugely costly. I mean, it is costly, but it’s not more costly than these other components that have been developed in the past. And generally speaking, everything I’m trying to propose is very much in the continuation quantitatively and politically and economically with some evolution that have actually been taking place in the past century. So I’m not dreaming about things which have nothing to do with what happened in the past. I’m really trying to look, OK, what happened in the past, what will be a logical next step if we just continue the evolution of what we’ve seen in the past.

EZRA KLEIN: And the argument you’ll hear in response, and this is an argument you heard against progressive taxation, income taxation, an argument that got made against things like Medicare and Social Security, but is, particularly at this scale, that you will wreck the economy. And in particular, for something like this, that you will do is that you will destroy the incentive — and here, I’m just making the argument — of the most innovative, creative, productive people, the people whose efforts do the most to push forward the total societal standard of living. Such that by doing this, it will look arithmetically like you are making people in the bottom 50 percent better off, but in fact, you’re making everybody worse off. Because you’re robbing people of the incentive to innovate. How do you respond to that argument?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Yeah, that’s an interesting argument at a purely theoretical level. But again, if I look back at my historical comparative evidence, I see very little support — or in fact, no support at all for this argument, for a couple of reasons. First of all, if you look at the long-run evolution, we’ve seen less concentration of wealth. So the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution today would have 60 percent in Europe, 70 percent in the U.S., as compared to 90 percent before World War I in Europe. This did not destroy the economy. If anything, this decline in the share of total wealth going to top 10 percent and the corresponding increase in the share going to the next 40 percent has contributed to a much faster economic growth in the 20th century than in previous centuries.

I think partly because it allowed more people to participate, to the economy. And also partly because it came also with the rise of education. And this was the true source of productivity in the long run, rather than the enormous level of inequality that we had before World War I. This theoretical discourse that more inequality, more concentration of wealth is always better for economic growth was made, of course, throughout history by people who had large concentration of wealth, certainly in Europe before World War I.

And this is a discourse that, in the 1980s, Ronald Reagan tried to tell Americans, basically tried to tell them, look we’ve gone too far with the New Deal, with Roosevelt, in terms of progressive taxation or wealth redistribution. We are going to cut top tax rate by two, where they’re going to go down to 28 percent or 30 percent, as compared to the 80 percent, 90 percent top tax rate under Roosevelt. So the promise that was made by Reagan during the 1980s was that cutting top tax rate might lead to more inequality, but will also lead to so much more innovation, more economic growth. And the incomes of average Americans are going to grow much faster than they used to grow.

Except that this is not what we’ve seen at all. So if you look at the three decades after Reagan, 1990 to 2020, the growth rate of national income per capita in the U.S. was only 1.1 — 1.2 percent as compared to 2 percent, 2.5 percent in the period of 1950 to 1980, or 1950 to 1990, which itself was not particularly exceptional. It was the same — 1910 to 1950, it was about 2 —2.5 percent. 1870 to 1910, around 2 percent. So in fact, the post-Reagan period, 1990-2020 has been particularly bad in terms of growth rate of national income per capita, which at the end of the day is the best economic measure we have of the increase in productivity and this should reflect innovation, et cetera.

So this policy experiment has been a failure, in the sense that we’ve not seen this enormous increase in the size of the pie that was supposed to justify this policy. Certainly, we’ve seen the increase in inequality. Billionaires today are hugely richer than what they were 30 or 40 years ago. But for the average American, we’ve not seen the increase in purchasing power. And I think this disappointment, to say the least, following the Reagan decade, is at the origin of many of the political troubles that we’ve seen in the U.S. in the past 10 to 15 years. And in particular, the fact that the Republican Party, which at the time of Reagan was sort of very optimistic about the power of the market, and the power of globalization, and the power of economic incentives, and of trickle down economics, well, 30 years later, had to come with a different story.

Because since the incomes of average Americans were actually not growing as was told before, then people like Donald Trump had to come with a different narrative, typically saying, OK, this is the fault of the Mexican, of the Chinese, of the rest of the world, that has been stealing the hard work of Americans. And this has become more and more frightening in a way. And I think this is partly the consequence of this failure of Reaganism.

So to summarize, this theoretical claim that richer billionaire or more inequality leads to faster economic growth, it’s a very interesting theoretical claim from a purely abstract and theoretical perspective. But we are talking about serious issues, which have serious consequences on our society. So we cannot just do theoretical claims. We need to look at actual data, actual facts. And again, if you look at the big picture, you compare growth rate, you compare level of inequality across periods, across countries, the conclusion is that we don’t need this kind of level of extreme inequality in order to grow.

I’m not saying you want complete equality. I think you need income gaps of maybe 1 to 10. Some people would say 1 to 20. My reading of the historical evidence I have is that 1 to 10 or even 1 to 5 is probably sufficient to get the right incentives. But certainly, 1 to 100, or 1 to 200, or 1 to 1,000, this is completely useless. If I compare different historical period, the different societies, it’s very hard to make the case that we need such extreme level of inequality.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

EZRA KLEIN: So to stay on the idea of participation, because I really like that line in your idea of participatory socialism, so this kind of wealth redistribution would give people a lot more bargaining power to participate in society on more equal ground, to chase opportunities, to follow passions and ambitions. But you also push for something else, which I think is very interesting, and was something that was, in various ways, proposed by some Democrats in 2020, which is worker co-determination. Can you talk through what co-determination is and why you think it’s so important?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Right, so here again I am trying to start from what has been successful during the 20th century and to see how we can push it further. So in the 20th century, an interesting policy innovation, together with progressive taxation, which happened in the U.S. and in many European countries, another interesting policy innovation, which took place in Sweden, in Germany, and more generally Nordic Europe, was what is sometimes called co-determination or co-management, which is the fact that workers’ representatives have a significant voting rights in the board of companies, even if they don’t hold any share in the capital stock of the company.

So the way it works in Germany is that worker representatives can have up to 50 percent of voting rights in the board of large corporation, in the case of Germany. So shareholders still have 50 percent plus 1. So if there is a tie, they can make the difference. But still, this means that if, in addition, the workers have a small capital share in the stock of the company, say 10 percent or 20 percent of the capital, or if a local or regional government has 10 percent or 20 percent of the capital, which sometime happen in Germany, then this can shift the majority. And basically, you can get the majority of the vote, even in front of a shareholder who has 80 percent or 90 percent of the stock.

So I can tell you that from the point of view of a shareholder, this is like communism. And shareholders in my country, in France, or shareholders in Britain or in the U.S. will not like at all this system. Except that this was applied, not in some tiny, obscure countries, this was actually applied in Sweden, in Germany. And this has been like that since the early 1950s. At the time, shareholders did not want to hear about that. But the balance of power in the specific context of after World War II in these countries led to this institutional transformation. And 70 years later, nobody wants to change that in Germany and Sweden. Nobody could change that.

Because what people have seen is that not only this has not destroyed the capitalist system, the economy, otherwise we would have noticed it, just like for progressive taxation under Roosevelt, but in fact, this allowed for better involvement of workers in defining the long-run strategy of the company. And workers, in a way, are investors in labor in the company. And sometimes, they are more serious and committed long-run investors than many of the short-term financial investors that we see. And so getting them to be involved in defining the long-run investment strategy of the company can be good.

So how can we move further in this direction? Well, in my book, I discuss various options, but I say first it should be extended to other countries. This should be extended to firms of smaller size. And in addition, if you want to go further in this direction, what we could do is to say, OK, you have 50 percent of voting rights for a worker representative, 50 percent of voting rights for shareholders. And within the 50 percent of voting rights going to shareholders, maybe there should be a maximum, maybe 10 percent or 5 percent of voting rights, that a single shareholder could have in a very large corporation.

We live in a very educated society, where millions of engineers, technicians, managers have something to contribute. The idea that you should have these monarchical organization of power in companies is in a way completely at odds with the current reality.

EZRA KLEIN: So I agree with this. I’m a very — a very big supporter of co-determination. But one thing I think about co-determination is that the experience we’ve seen with it in Germany, it both undermines the right wing argument against it, because Germany has grown great. It’s a very innovative economy. They have a great manufacturing sector. In many ways, a model. And also, I think should probably want to moderate how much you think it’ll do for the economy.

If I look at — I’m looking at income inequality here, which is not as good as what you’re looking at with wealth inequality, but I forgot to bring the right chart with me. But Germany looks about France, and the Netherlands, and Canada, a little bit lower, but not much. And growth is not super different in Germany than some of these other cases. So why do you think co-determination would do all that much? Why do you feel that it’s more than a marginal change in how the economy works?

THOMAS PIKETTY: Well, first of all, I’m not saying this is a magic bullet. I think it has to come together with a whole other set of policy, including the redistribution of wealth itself. So that’s why the minimum inheritance and the progressive tax on wealth, which you don’t have in Germany, is so important. Because if you don’t redistribute wealth itself, co-determination moves are not going to be sufficient. It also has to come with a system of true real access to high-quality education, which we don’t have in any country.

And finally, don’t forget that the co-determination rules in Germany, so far, only apply to very large companies. Basically, it’s over 1,000 or 2,000 workers. If you are in a company of 100, 200, 300, let alone a company of 10 or 20 workers, this is not — so despite all of its limitations, I think co-determination rules have contributed both in Germany and Sweden to limit the huge rise of very top compensation, as compared to, in particular, the U.S. and Britain. But, yeah, the idea is to go further in this direction by first extending this 50 percent of voting rights to all firms, small and large, and also to put a limit on the power of individual shareholders.

Because in some cases, with the current co-determination rule, at the end of the day, the shareholders have the decisive vote. So it doesn’t have as much impact as it could have.

EZRA KLEIN: I think your vision for the future deserves to stand on its own, so I don’t want to tie you up in what’s happening in economics right now. But I do want to ask one question I think will be in people’s minds, which is these are big proposals, they would move a lot of money around. And at the same time, we’re living through a really quite unusual, although maybe not historically so, surge in inflation. There’s been a dominant view, particularly in the U.S., pushed by Larry Summers and others, that some of it has come from too much redistribution, too much stimulus.

How do you understand inflation and prices as part of this? How do you understand either the inflation rise at the moment? And how do you understand the dangers of inflation, either for the politics — it would produce these kinds of policies, or as an outcome of these kinds of policies?

THOMAS PIKETTY: So the short answer is that I want to finance redistribution through progressive taxation, not through money creation. So money creation and issuing public debt can be justified in some context, but clearly, in the long run that’s not going to work. We know that. So my view of redistribution is that this should be paid for by progressive taxation and the wealthy. And the good news is that the wealthy are very wealthy.

And you look at the billionaires today, the wealthiest people have $200 billion or so. 10 years ago, they had 30 or 40 billion or so. And 10 years before, they had only $10 billion or so. You can see immediately that the rise of these very top wealth people has nothing to do with the rise of the size of the world economy. Because they are rising a lot faster. There have been some — there’s been some rises in the size of U.S. economy or world economy in the past 10 years, but it has not been multiplied by three or four.

So you cannot continue like this. And that’s — of course, that’s the way to pay for the redistribution. And I’m not saying everything is going to come from billionaires. Millionaires also will have to pay. But if you don’t start by asking your fair share to billionaire, it’s going to be very hard to convince millionaires that they also have to pay.

EZRA KLEIN: And so I think that’s a good place to end. So always our final question, what are three books that have influenced you that you would recommend to the audience?

THOMAS PIKETTY: There are so many books, it’s hard to say. To go back through time, there’s an excellent book on the French Revolution written by a Rafe Blaufarb, called “The Great Demarcation,” which I really recommend. I think it’s a great book about the invention of the modern property system during the French Revolution and how complex the discussion was at the time. And I think it’s fantastic.

Another book, talking about the much more recent period, at least about the 20th century, is the book by Or Rosenboim, which is about the history of globalization, which is “The Emergence of Globalism: Visions of World Order in Britain and the United States, 1939-1950.” It also talks about Europe.

I think it’s very interesting because it talks about this moment just before World War II and just after World War II where people realize that we are shifting to a new world system and they are starting to think about new forms of federal organization of the world system, with lots of deceptions in the end, lots of failures, but also lots of hope and lots of achievement. And I think it’s a very useful book to think about also the situation in which we are and in which we could end up in the future.

And third book I would recommend, which I was also very impressed by, actually rereading a book by Hannah Arendt, “The Rise of Totalitarianism,” which I did not realize how much she was also talking about the issue of federalism and democratic federalism. And the fact that in the interwar period, the failure of social democracy and social democratic parties is that they were — I mean, they pretended to be internationalists, of course, in their general ideology. But in their actual political projects and political practice, they were maybe the only players around that did not take seriously the fact that with the world economic system, you need some kind of world politics.

And you need to have some form of democratic federalism to think about global regulation of capitalism, global taxation. In a way, it’s one of the biggest challenge ahead which we have, which is that if the lower income groups voted for Brexit or also voted against Europe in every single referendum we’ve had in Europe, including in France in 2005 and 1992, you cannot just say, oh, OK, this is because these people are nationalists or racists or whatever.

I think we have to — I am a strong federalist, not only at the European level, but at the broader international level. But we have to make federalism something like social federalism. It must be to the service of a better redistribution of wealth, of a more equitable distribution of income, of common progressive taxation of the multinationals, high wealth individuals.

And if we don’t transform not only Europe, but more generally the organization of our world economic system in this more equitable manner, I think we will confront enormous difficulties, especially as developing countries in the South are going to have to pay partly for the damage that we have created with global warming in North America and in Europe. And I think there’s a serious risk also that China will be, in the end, able to propose to countries in the South alternative ways to finance for their development strategy.

And I think we are really at a time where if we don’t think of another form of organization for the world economic system, things can turn really bad. And rereading some of this work and some of the thinking on mid-20th century globalism I think is a useful reading for that.

EZRA KLEIN: I think there’s a lot of wisdom in that. And I will say, if people are interested in the Arendt book, “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” a couple of weeks ago on the show I had on Anne Applebaum for discussion all about that book and what it teaches us today. So you might be interested in that. Thomas Piketty, thank you very much.

THOMAS PIKETTY: Thanks a lot, Ezra.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

EZRA KLEIN: The Ezra Klein Show is produced by Annie Galvin, Jeff Geld, and Roge Karma, fact-checking by Michelle Harris and Kate Sinclair. Original music by Isaac Jones. Mixing and engineering by Jeff Geld. Audience strategy by Shannon Busta. Our executive producer is Irene Noguchi. Special thanks to Kristin Lin and Kristina Samulewski.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Real conversations. Ideas that matter. So many book recommendations.

Listen to “The Ezra Klein Show”: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, How to Listen

Spread the word