Last year was a bad one for incumbent political parties, as voters worldwide rebelled against representatives of the status quo. It was a bad year for the left, with Donald Trump winning in the United States and reactionary nativism advancing across Europe. And it was a bad year for women in politics; as the BBC reported, in 60 percent of the countries that had elections in 2024, the number of women in legislatures fell.

One country, however, bucked all these trends: Mexico, where Claudia Sheinbaum, heir apparent of the flamboyantly disruptive left-wing leader Andrés Manuel López Obrador, won the presidency in a landslide.

A secular Jewish climate scientist, Sheinbaum is in many ways the antithesis of the swaggering strongmen who make this moment in world politics feel so suffocating. I’m talking not just about Trump and Vladimir Putin, but also the new techno-caudillos of Latin America, figures like El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele and Argentina’s Javier Milei, who combine far-right politics with the postmodern smirk of message-board trolls.

Around the globe, liberal humanism is faltering while the forces of reactionary cruelty are on the march. So Sheinbaum, who has adopted López Obrador’s slogan “For the good of all, first the poor,” can seem like a shining exception to the reigning spirit of autocratic machismo.

“I feel very proud about her,” Marta Lamas, an anthropology professor and leading Mexican feminist who has known Sheinbaum for years, told me in Mexico City last week. “She is a light in this terrible situation that we are facing: Putin, Trump.”

Lamas said she’d feared a sexist backlash against Sheinbaum, Mexico’s first female president, but six months into her term, there’s no sign of one. Sheinbaum was elected with almost 60 percent of the vote. Today her approval rating is above 80 percent. Last week, Bukele, who likes to call himself “the world’s coolest dictator,” asked Grok, Elon Musk’s A.I. chatbot, the name of the planet’s most popular leader, evidently expecting it would be him. Grok responded, “Sheinbaum.”

For those of us steeped in American identity politics, it can be hard to understand how a woman like Sheinbaum came to lead the world’s 11th-most-populous country. Her parents, both from Jewish families that fled Europe, were scientists who’d been active in the leftist student movement of the 1960s. As a child, Sheinbaum was dedicated to dancing ballet, a discipline that still shows up in her graceful posture and in the many social media videos of her doing folk dances with her constituents. She did research for her Ph.D. in energy engineering at UC Berkeley and shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for her work on the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

She is, in short, part of the cosmopolitan intelligentsia typically demonized by populist movements. But as I was told again and again in Mexico, her rarefied background meant little in light of her close relationship with López Obrador, who she’d worked beside since he was mayor of Mexico City 25 years ago, and whose economic populism earned him the enduring devotion of many downtrodden citizens.

As president, López Obrador more than doubled the minimum wage and pegged it to inflation to ensure that workers wouldn’t fall behind. He enacted broad social programs, including stipends for young people doing job training and, most important, universal cash transfers for the elderly. According to Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy, five million Mexicans escaped poverty during the first four years of his presidency. (Extreme poverty, however, increased by nearly half a million.)

Ahead of the last election in 2024, a Gallup poll found that Mexicans were more optimistic about improvements in their own living standards than at any other time since Gallup began surveying the country.

Some Mexican economists see their country’s expanded welfare state, which Sheinbaum hopes to grow further, as unsustainable. They note that López Obrador didn’t raise taxes on the rich to pay for it, instead relying on deficit spending and severe cuts to other parts of the government. Overall economic growth was slow during his presidency, and the health care system declined precipitously.

Carlos Heredia, a left-leaning Mexican economist and onetime adviser to López Obrador, criticizes the former president for handing out money rather than investing in education and, especially, health care. “Instead of establishing and improving a functioning system that belongs to the users,” Heredia said, “what we have is a disaster.”

But whatever the argument against cash transfers as policy, they are excellent politics. Money in people’s pockets is simply more tangible than even the wisest improvements in public services. Francisco Abundis, the director of the public opinion research firm Parametrics, told me that by giving people cash, López Obrador’s administration also gave them a measure of self-respect, a feeling of being seen and valued by their government. Retirees, he said, gained independence and enhanced status within their families from their ability to contribute.

“It was a matter of dignity, the role they play,” he said. During López Obrador’s presidency, said Abundis, about one of every four Mexican adults had received government aid, but that support also benefited their relatives, so 48 percent of people who went to the polls last year said they’d received money from the government.

Mexico’s voters, then, weren’t looking for change last year. The country’s presidents, however, can serve only a single six-year term. Unable to run again, López Obrador anointed Sheinbaum, a woman known for steely competence and intense loyalty, as his successor, and his record propelled her into office.

Not surprisingly, some leftists in the United States have latched on to Sheinbaum as a rare symbol of progressive success. Her ascendance seems like evidence that the road to victory lies in running against entrenched economic elites and delivering concrete material benefits to people who are struggling. In other words, it’s a data point supporting the politics of people like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

When I spoke to Representative Ro Khanna of California in January, he described Sheinbaum’s victory as “an example of working-class politics working.” At a forum for left-leaning New York City mayoral candidates last month, the democratic socialist and social media phenomenon Zohran Mamdani drew cheers when he promised to take “a page from neighbors like Claudia Sheinbaum in Mexico who has shown what can be won when you’re willing to fight.”

During Trump’s first term, the young, liberal New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was sometimes held out as the “anti-Trump.” Now, said Waleed Shahid, a progressive Democratic strategist, Sheinbaum occupies a similar place in the left-wing imagination, as an “intelligent, inclusive, social democratic” woman offering an alternative to the brutish rule of oligarchs.

Obviously, Mexico is different from the United States in too many ways to list, and it’s simplistic to assume that what works in that country would translate north of the border. But in America, as in so many other places, there’s a revolt against a style of politics — often short-handed as neoliberalism — that vests too much power in markets, ceding the ability of government to promote collective flourishing.

Because this revolt has led, in the United States and elsewhere, to unremitting ugliness, it can sometimes feel like our only choices are neoliberalism or barbarism. Sheinbaum is one of just a few world leaders offering hope for a different path.

It is, in Mexico’s case, a fragile hope; the country has a weak economy and is besieged by cartel violence. Trump has been a boon to Sheinbaum’s popularity, but his policies could still wreak havoc, even if Mexico has so far been spared the worst of his tariffs. If her presidency succeeds in spite of all these challenges, it will be a source of inspiration in a world increasingly bereft of it.

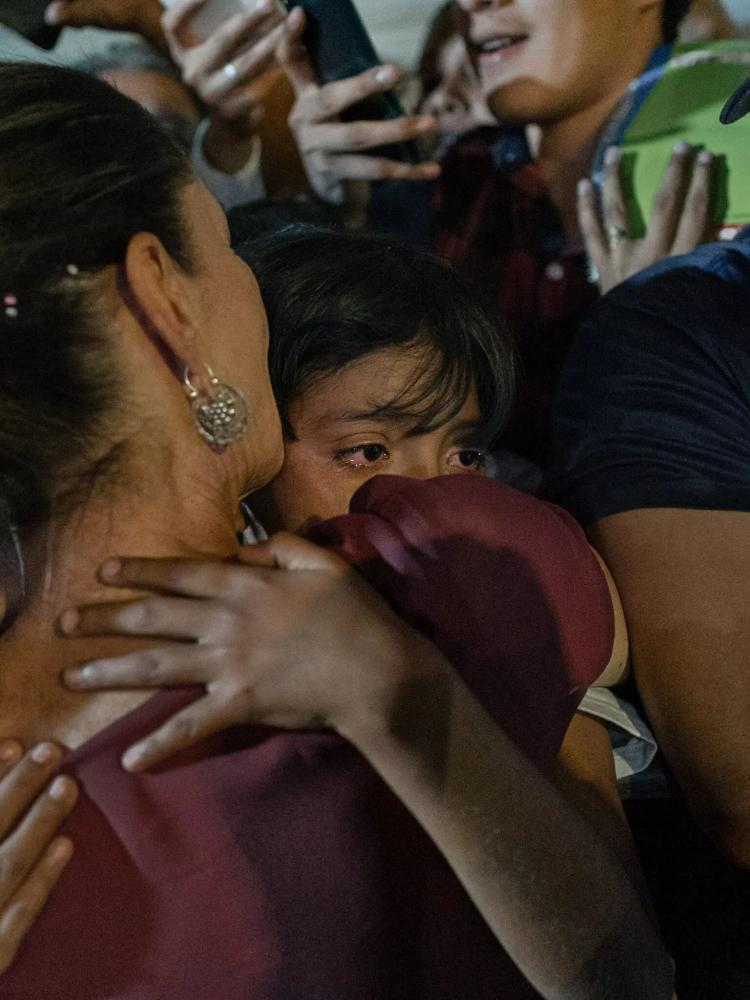

Luis Antonio Rojas for The New York Times

Many Mexican liberals find foreign romanticization of Sheinbaum exasperating, a projection that says more about American despair than Mexican reality. She is, after all, López Obrador’s protégé, and they see him as an analogue to Trump, not an antidote.

“Left-wing populism is not a democratic alternative to right-wing populism,” said Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst in Mexico City. “It’s still authoritarian, but it’s a more palatable authoritarianism.”

López Obrador, it’s important to note, oversaw significant democratic backsliding, leading attacks on the media, watchdog agencies and, most recently, Mexico’s independent judiciary. He was an audacious, bombastic figure who reveled in insulting his enemies during his daily morning press conferences, or mañaneras, which included a regular segment calling out unfriendly journalists, “Who’s Who in Lies.”

Like Trump, López Obrador saw himself as the embodiment of the people’s will and his opponents in both politics and civil society as fundamentally corrupt and illegitimate. When the well-known journalist Carlos Loret de Mola published an investigation into the opulent lifestyle of López Obrador’s eldest son, López Obrador struck back by releasing a chart of Loret de Mola’s allegedly lavish income. It used information that Loret de Mola claimed came from confidential tax records.

The economist Luis de la Calle, a former Mexican trade negotiator, keeps in his office a handwritten two-page list of similarities between López Obrador and Trump, who he describes as “carbon copies.” For liberals like him, the big question about Sheinbaum is the degree to which she’ll follow López Obrador’s example.

“The true test for her,” he said, “is not going to be in economics and trade, which are important, of course. We’ll see whether she’s truly committed to democratic processes and the rule of law, equality before the law. That’s what’s going to define her term historically.”

But even though de la Calle is skeptical of Sheinbaum, he acknowledges that her character is very different from that of her political patron. She’s a self-described “lover of data,” a person known for her close attention to detail more than her ideological crusading. López Obrador set himself against “the tyranny of the experts,” said de la Calle. “She’s an expert.”

Sheinbaum’s ex-husband, Carlos Ímaz, helped found the left-leaning Party of the Democratic Revolution, or P.R.D., which López Obrador led for three years in the 1990s. But she didn’t get to know him until shortly after he became mayor of Mexico City in 2000, when he tapped her to be his environmental chief, charged with dealing with the city’s notorious air pollution.

Impressed by her abilities, he put her in charge of a major infrastructure project, building a second story to the Periférico, the beltway around Mexico City. She grew into one of his most loyal allies; in 2014, when he formed his own populist party, known as Morena, she went with him. In 2018, the year he was elected president, she became mayor of Mexico City.

During her presidential campaign, Sheinbaum often said she wanted to build a “second story” to López Obrador’s political revolution. Many wondered, however, if she could maintain his fervent support without his brash charisma. At the start of her presidency, there was a broad sense that she was hemmed in by the need to remain faithful to him, even in areas where he was considered weak, like security policy.

López Obrador was reluctant to take on the cartels, which have deeply infiltrated Mexican politics and had allegedly funneled money to his failed 2006 presidential campaign. He once argued that the gangs “respect the citizenry,” and he tried to address the country’s epidemic of cartel violence through programs to give would-be recruits better options, a policy dubbed “Hugs Not Bullets.”

While the homicide rate dropped slightly toward the end of his presidency, it remained exceptionally high, with over 30,000 killings in 2023. In 2022, Reporters Without Borders declared the country the deadliest in the world for journalists.

In polls, Mexicans gave López Obrador low marks on security, but several people told me that his core followers would see any attempt to break from his policies as a betrayal. “People love López Obrador,” said Lamas, the anthropology professor, who served on an advisory board for Sheinbaum during her mayoral campaign. “You go out to rural communities and he’s God. You’re not going to fight with God.”

Yet if Sheinbaum’s room for maneuvering was initially somewhat narrow, Trump has done a great deal to expand it. She’s earned widespread praise, including from critics of López Obrador, for her deft handling of his erratic tariff threats.

Sheinbaum has flattered Trump without appearing supine; he’s called her “tough” and a “wonderful woman.” Unlike Canadian leaders, who’ve been shocked by American belligerence and have channeled the fury of their populace, she’s been stoic and strategically patient in announcing retaliatory measures. She frequently uses the phrase “cabeza fria” — cool head — and people just as often use it about her.

“She has been incredibly good at managing time,” said Bravo Regidor, the political analyst. Trump, he pointed out, initially imposed 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada on March 4. Sheinbaum announced that she would have a phone call with him two days later and then unveil Mexico’s countermeasures at a rally two days after that. That gave time for pressure from American industries hit by the tariffs to build, and on the same day Trump spoke to Sheinbaum, he declared that the tariffs would be delayed.

Though Trump seemed to give Sheinbaum credit for the move, it’s unclear how big a role their conversation truly played, since Canada got a reprieve as well. Nor does the public know what she might have offered Trump in return. But at least in Mexico, it looked like Sheinbaum’s call had worked wonders. “She didn’t have a great hand, but the hand she had, she played well,” said Bravo Regidor.

Trump has since imposed tariffs on Mexican exports that aren’t covered by the U.S.M.C.A., the trade deal he negotiated with Mexico and Canada during his first term. Still, Mexico has fared far better in its economic dealings with the new Trump administration than many other countries. On Wednesday, when Trump unleashed a new round of so-called reciprocal tariffs, both Mexico and Canada were excluded, to Mexico’s profound relief. Héctor Cárdenas, president of the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations, predicted official celebrations, and though he hadn’t voted for Sheinbaum, he thought she’d earned them.

“I don’t know if ‘triumph’ is the right word, but it’s an outcome that Mexico can live with,” he said. “Now, of course, we don’t know what will come next week.”

Cárdenas has also been impressed by the way Sheinbaum has used Trump’s pressure to her advantage in tackling organized crime. There’s significant fear in Mexico that Trump could unilaterally bomb the country’s drug cartels, an idea that’s become increasingly mainstream in Republican circles. Already, Trump has issued an executive order designating foreign cartels as international terrorist organizations, and he’s reportedly considering declaring fentanyl a “weapon of mass destruction.”

“There’s a higher likelihood of U.S. military action in Mexico than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere,” Brian Finucane, a senior adviser to the International Crisis Group, told me. Such an action would all but guarantee a nationalist uproar in Mexico, making it impossible for Sheinbaum to cooperate with the United States on drug trafficking or immigration.

The need to maintain Mexico’s relationship with America has given Sheinbaum cover to go after the cartels without disavowing the approach of her predecessor. In December, Mexican authorities seized over a ton of fentanyl in the state of Sinaloa, the largest such bust in the country’s history. In February, the country extradited 29 alleged narcotraffickers to the United States. “We have never seen such an overwhelming and daily operation against the cartels,” a Sinaloa journalist told The Associated Press.

It remains to be seen whether Sheinbaum’s more technocratic temperament will lead to more liberal governance. Just before leaving office, López Obrador pushed through a constitutional change that, among other things, made judges elected, rather than appointed, officials. Though this was popular with the public, legal experts widely saw López Obrador’s maneuver as undermining the rule of law; The Journal of Democracy described it as “a last-ditch effort in his longstanding plan to undermine democracy in Mexico.” Stripping judges of their independence, after all, is a move straight from the authoritarian playbook, one that has been used in countries as diverse as Turkey, Hungary and Israel.

Some in Mexico hoped that Sheinbaum might water down the judicial changes. Instead, she moved quickly to carry them out. Lamas believes Sheinbaum would have preferred to slow-walk the remaking of the judiciary, but that doing so was politically impossible, since they were so important to López Obrador.

“I know her,” she said. “I think she wants judicial reform, but not this year, in this moment with all the problems she’s facing, economic problems, Trump problems. This was not the moment to do it, but she had a compromise with López Obrador to do it now.”

It’s an open question whether, as Sheinbaum accumulates more of her own political authority, she’ll have either the desire or the will to stop the dismantling of Mexican institutions that might provide a check on her and on future presidents. In the past, the United States exerted diplomatic pressure on Mexico to maintain independent courts and other structures undergirding liberal democracy. But liberal democracy is not, to put it mildly, a priority for the Trump administration.

And Morena partisans I spoke to are dismissive and a little baffled by accusations that Sheinbaum is traducing democratic principles. “It’s difficult to say that this government and the previous one are not democratic, considering the amount of popularity they have,” said Vanessa Romero Rocha, a lawyer and member of a government committee vetting judges to run for office.

An easy riposte is that democracy means more than just elections. But that argument is convincing only if you’ve already accepted that liberal democracy is a superior system, and it’s increasingly clear that many people do not. In elections across the globe, we’re seeing how little many voters care about abstract liberal proceduralism; they’re happy to cede power to the executive branch if they think it will improve their lives.

I find this trend tragic, but there are no signs that it’s going to reverse any time soon. Given this reality, we should judge politicians not just on how they amass power, but also on what they do with it.

In the United States, centralized authority has allowed Musk, inspired by Argentina’s Milei, to take a metaphorical chain saw to all sorts of federal programs, including those that help the most vulnerable. Sheinbaum, by contrast, is trying to build a national care system for children, the disabled and the elderly, lifting the burden of unpaid labor from many Mexican women. American progressives should be cautious about projecting their desperation for a heroine onto Sheinbaum. But at least right now, her kind of populism looks far better than the alternatives.

Last year, Bravo Regidor was an author of an essay in The New York Review of Books about López Obrador’s “constitutional chicanery and disregard for the law,” which warned that Sheinbaum could follow in his footsteps. Bravo Regidor’s fears haven’t been entirely assuaged. Still, he says, “When you look at the rest of the world, we’re not that bad.”

Michelle Goldberg is an American journalist and author, and an op-ed columnist for The New York Times. She has been a senior correspondent for The American Prospect, a columnist for The Daily Beast and Slate, and a senior writer for The Nation. (Wikipedia)

Spread the word