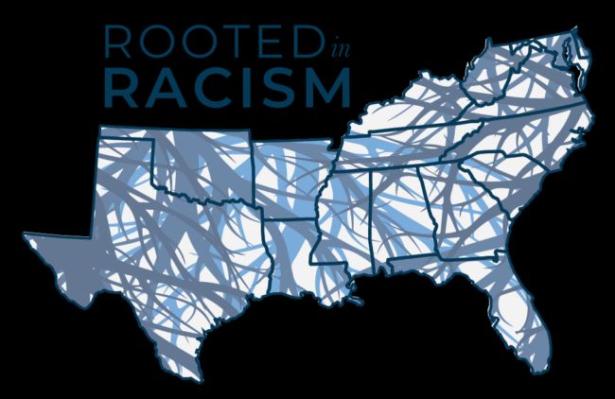

How Anti-Worker Policies, Crony Capitalism, and Privatization Keep the South Locked Out of Shared Prosperity

Key findings

-

Many states across the South use an economic development model that prioritizes the wealthy and corporations at the expense of workers and their families and fosters precarity to maintain racial and class-based hierarchies.

-

Southern families face high rates of economic insecurity, and underinvestment in health, child care, and transportation infrastructure blocks working families from full participation in the economy.

-

Southern states have some of the weakest wage theft and paid sick leave laws in the country and are less likely than other states to enforce laws that do exist to protect workers.

-

The racist attitudes that inspired discriminatory social welfare programs 90 years ago persist today. These dynamics are especially acute in the South, where the programs are less generous and reach fewer eligible families.

-

Many Southern lawmakers have repeatedly rejected efforts to expand Medicaid in their states, which has led to thousands of premature deaths and other health and economic consequences. And Southern states account for six of the 10 states nationwide with the highest uninsured rates.

-

In 11 Southern states, the poorest 20% of residents pay more in sales taxes alone than the top 1% of residents pay in all state and local taxes combined.

-

High poverty rates, regressive tax structures, and a failure to tax corporate income means that Southern states collect much less revenue than other states and are highly dependent on the federal government.

-

In recent years, Southern states have given away billions of dollars in public revenue in the form of direct subsidies and tax breaks to corporations for projects that often do not benefit communities.

Why this matters

When policies in the South fail to raise adequate revenue to pay for public goods and services, these same harmful policies are leveraged as “the cure,” creating a vicious cycle that keeps millions of Southerners locked into poverty and out of the benefits from economic growth.

How to fix it

The Southern economic development model is the result of policy choices that can and must be undone for the South to thrive. The racism and anti-worker sentiments that have influenced economic policymaking in the South for generations must be uprooted and replaced by new policies centered on empowering and investing in workers, families, and communities.

Full Report

The central function of government should be to protect people from harm, exploitation, and abuse. Yet on this core task, many Southern state governments have performed abhorrently—largely by design. EPI’s Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation series1 has shown how for most of the past two centuries, Southern state governments have embraced an economic development strategy—the Southern economic development model—designed to undermine job quality and suppress worker power, particularly for Black and brown workers. The model aims to maintain a pool of exploitable, available labor, and preserve the racial and economic hierarchies established during slavery. This strategy has led to poor job quality for Southern workers of all backgrounds; economic growth that has underperformed much of the rest of the country; persistently higher poverty rates; and the lowest economic mobility of any U.S. region (Childers 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2025).

These poor economic outcomes are both a consequence and an instrument of the Southern economic development model. By generating precarity, the Southern model weakens workers’ ability to reject low-quality jobs. Workers in poverty typically have few, if any, assets on which to rely in the event of a lost job. They have fewer resources with which to move to new areas and seek out better job options. They are more likely to face health challenges and will have a harder time fulfilling any care needs—either for themselves or a family member.

It should come as no surprise then that one component of the Southern model has been to do as little as possible to protect workers’ well-being on the job, in their lives outside of work, and the lives and well-being of their families. In this report, we describe how Southern state lawmakers have consistently made policy choices weakening enforcement of workplace wage, hour, and safety laws. They have sought to limit workers’ and families’ access to social safety net programs, leading to fewer families receiving the aid for which they are eligible, and providing notably ungenerous benefits to those who do receive benefits. Southern policymakers have also failed to invest in child care access, quality, and affordability; refused to protect renters and homeowners or provide those facing financial hardship with relief; and have deprioritized safe, reliable, and climate-friendly transportation policies while giving away public funds to corporate polluters.

Instead of investing in essential public goods and services that would allow communities to achieve a better standard of living, proponents of the Southern economic development model have sought to eliminate or block regulations that govern the private sector and protect workers, to reduce taxes on the wealthy and corporations, and to shrink the functions of the public sector—replacing them with private, for-profit services. The supports that Southern governments do provide are frequently geared toward businesses—large economic development packages, often with few strings attached—that have limited public benefits while reducing funding for essential services like public education.

This report highlights how Southern lawmakers have wielded the power of the state to protect and support businesses and the wealthy at the expense of working people and families. It covers many issue areas, including labor standards enforcement, environmental regulations, taxation and public spending, public education, and social safety net programs. As described throughout this series, these policy choices are often rooted in anti-Black racism and the desire to subjugate and control workers of color economically, politically, and socially.

Southern lawmakers have disinvested in labor standards enforcement, leaving workers at higher risk of abuse by employers

When it comes to protecting workers from having their wages stolen by employers, from being forced to choose between working while sick or going without pay, and from enduring other harms at work, Southern states have some of the weakest laws in the country and are less likely than other states to enforce those laws that do exist to protect workers.

According to 50-state analysis of state minimum wage law enforcement capacity, penalties for noncompliance, and the availability of additional legal remedies for victims of wage theft, Southern states have most of the lowest rankings. Seven of the 10 worst states for the enforcement of wage and hour laws are in the South: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia, Florida, Tennessee are the six worst, and North Carolina is #10. Mississippi has no wage and hour laws at all, Alabama only regulates child labor, and Florida—which has the fifth weakest labor laws in the country—has no state Department of Labor to investigate labor violations and enforce laws protecting workers (Florida Policy Institute 2022; Galvin 2016).

A 2017 EPI analysis of wage theft in the 10 most populous states—including Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas—found that workers were cheated out of $8 billion annually due to minimum wage violations alone (Cooper and Kroeger 2017). In those four Southern states, over 800,000 workers lost nearly $3 billion annually due to minimum wage violations (see Table 1).2

Table 1

Florida had the highest rate of minimum wage violations across the 10 most populous states with one-quarter of low-wage, minimum wage-eligible workers in the state—over 400,000 workers—being underpaid. More than double this number of workers (835,000) experience wage theft across these four states collectively. Wage theft is rampant in these states in part because their governments fail to regulate businesses and enforce the minimal labor standards that do exist, whether local, state, or federal. States with weaker labor laws tend to have higher rates of wage theft and Southern states have some of the weakest labor laws in the country (Galvin 2016).

Though state Departments of Labor and Attorneys General play an important role in enforcement— their efforts accounted for around 19% of stolen wages recovered between 2017–2020—many Southern states do not recover stolen wages on behalf of workers (Mangundayao et al. 2021). Of the seven states that do not recover wages for employees, six are Southern states. In Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, workers whose wages are stolen must seek redress either through the federal U.S. Department of Labor—which has just 611 wage and hour investigators responsible for protecting workers in all 50 states and territories or 1 investigator for roughly 270,000 workers3—or through class action litigation—which more than half of workers are barred from joining due to forced arbitration clauses in their employment contracts (Barnes et al. 2025; Poydock and Zhang 2024).

Southern states that do conduct wage theft enforcement are chronically understaffed. In Texas, for example, 80% of approved wage theft claims from an 11-year period still had not been paid out three years later (Galvin et al. 2023). Just as Southern lawmakers have vociferously blocked efforts to strengthen labor standards such as the minimum wage, paid sick leave, and workers’ organizing rights, they have chosen to not dedicate public resources to policing bad employers. They have prioritized businesses’ profit interests over workers’ right to be paid the wage they’ve earned and their ability to enforce that right.

Rampant wage theft is an unsurprising outcome of an economic agenda governed by low wages and anti-worker policies

Southerners are more likely than workers in other regions to be paid low wages, a result, in part, of relentless opposition to higher minimum wages by Southern lawmakers and their business allies. To take just one example, a bill to increase the minimum wage in Georgia has been repeatedly introduced since the federal minimum wage increased to $7.25 in 2009. Yet over the past 16 years, lawmakers have repeatedly failed to enact such legislation, leaving the statewide minimum stuck at its 2001 rate of $5.15 (GSU 2012). Since Georgia’s minimum wage remains $2.10 less than the federal minimum wage, most workers in Georgia earn at least $7.25 an hour (because federal law preempts lower state wage standards).

While the federal minimum wage is also far too low to support a basic living standard for workers in 2025, Southern states are even further behind. Only six Southern states and the District of Columbia have a higher state minimum wage than the federal minimum—Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia (EPI 2025b). Arkansas and Florida only have higher minimum wages because their residents voted to raise their statewide minimum wage through the ballot measure process, not because state politicians chose to raise wages for the lowest earners. This fact is not lost on Arkansas and Florida’s lawmakers, who have used various tactics to block the will of the voters. This year, Florida Republicans proposed a bill to let employers ask young workers to “opt out” of the constitutionally mandated minimum wage, and Arkansas lawmakers have passed a slate of bills to make it more difficult for citizen-led ballot initiatives to be considered (Rohrer 2025; Vrbin 2025).

When Southern localities have attempted to raise wages and workplace standards in response to weak standards statewide, state legislatures have frequently used harmful state preemption laws to block these ordinances from taking effect. In the South, preemption has been used as a means of entrenching white racial and economic supremacy against the will of majority-Black or majority-brown cities and counties and their elected officials. It is embedded in a long history of anti-Black racism, and it is more common in the South than anywhere else in the country (Blair et al. 2020). Additionally, in order to maintain an unbalanced labor market and block workers from unionizing to advocate for higher wages and better working conditions that unions afford, Southern policymakers have implemented right-to-work policies and bans on public-sector collective bargaining (Gould and Kimball 2015; Childers 2023; Morrissey and Sherer 2022).

Intentional disinvestment in public goods and services keeps workers and families economically insecure

Anti-poverty programs and the social safety net were structured to maintain racial hierarchy and economic precarity

Race is a social construct used to justify the subordination and enslavement of Black people. Negative stereotypes associated with Blackness—narratives of criminality, laziness, and immorality—were fabricated to maintain racial hierarchy and exclusion (DiTomaso 2024; Melson-Silimon, Spivey, and Skinner-Dorkenoo 2023). After slavery was abolished, Black Americans were forced into menial, dangerous, and low-paying jobs formerly dominated by enslaved labor: agricultural work, domestic work, and other manual labor. Then, the jobs they were segregated into were excluded from federal programs as a means of blocking Black people from accessing these benefits.

The 1935 Social Security Act (SSA), which created a social insurance program for workers after retirement and established Medicare, unemployment insurance, and cash assistance for low-income families (Aid to Dependent Children or ADC), excluded agricultural workers from eligibility for these benefits. Since Black workers were overrepresented in these jobs, the SSA served primarily to benefit white workers in its initial decades and excluded Black workers until key changes to the Act expanded its protections. To maintain racial oppression, Southern members of Congress lobbied to allow states to administer ADC themselves and to strip the SSA of a clause on ensuring “a reasonable subsistence with health and decency” (Black and Sprague 2017). Like SSA more broadly, the ADC program overwhelmingly benefited white families (despite high rates of poverty among Black families) and was structured to coerce Black families into accepting low wages in farm work (Black and Sprague 2017). A 1987 House bill proposed a national minimum benefit standard for AFDC, but the legislation died in the Senate because Southern lawmakers opposed it (Floyd and Pavetti 2022).

Racist, anti-poor attitudes explain persistently low nutrition and cash assistance benefits for Southerners

The racist attitudes that inspired racially discriminatory social welfare programs 90 years ago persist today. For example, the public greatly overestimates the share of Black people that receive welfare benefits, and white people are less likely to support welfare programs if they believe that a large share of recipients are Black (Akesson et al. 2022). The intentionally stingy structure of public benefit programs, particularly in the South, also persists. Though racist attitudes are embedded in safety net programs across the U.S., Southern states have been particularly fervent in their disinvestment in social programs that benefit low-income families and families of color, reinforcing the harms of past policymaking. Of the 10 states that spend the least revenue per capita on public welfare expenditures, five are Southern: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Texas (Urban Institute 2022).

SNAP and Free School Lunch

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) address food insecurity among low-income people and low-income pregnant women and young children, respectively. SNAP is the largest anti-hunger program nationwide, reaching 88% of eligible individuals in fiscal year 2022 and an estimated 41 million people in an average month in fiscal year 2024. However, participation rates are lower in the South, and four states in the region are ranked in the bottom 10 for participation rates: Arkansas (59%), Mississippi (74%), Texas (74%), and South Carolina (76%) (Cunnyngham 2025).

Despite already low participation in these programs amid considerable need, Southern lawmakers have moved to limit SNAP further. Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, six Southern states declined additional SNAP benefits for their residents that the federal government made available (Hernández 2022). Three of the four states that proposed limiting access to SNAP in 2024 are in the South (Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, and West Virginia) (Higham 2024). Many of the proposals by Southern lawmakers to weaken SNAP are now being copied by the Trump administration, which has threatened to make drastic cuts to the SNAP program to pay for tax cuts for the wealthy (Ross 2025). These cuts would have a devastating impact on millions of families across the South that would go hungry if not for SNAP (Bergh 2025).

The National School Lunch Program is another federal food assistance program, which provides free or reduced-cost meals to school children across the country. During the pandemic, the federal government reimbursed schools for the full price of school breakfast and lunch for all students, regardless of income. The program was set to expire at the end of June 2022 but was expanded through the summer months thanks to the bipartisan Keep Kids Fed Act (Pérez and Fitzsimons 2022). Over two-thirds (29) of the 42 House Republicans who voted against the budget-neutral bill to expand free school lunches represent Southern states (U.S. Clerk 2022). Since the expanded program ended in September 2022, school districts have struggled to fill the gap between what the federal government will pay for meals and the true cost of providing them to students. School nutrition directors in the Southeast cited food, labor, and equipment costs as a “significant challenge” at statistically significantly higher rates than the overall rates (the only region to do so) (School Nutrition Association 2025).

Cash assistance

Federal cash assistance programs date back to 1935, with the creation of Aid to Dependent Children, later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). From the very beginning, this program systematically excluded or discriminated against Black women and other women of color (Floyd et al. 2021). Racial discrimination in and exclusion from past programs endures today in the form of significant racial disparities in access to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). TANF was the result of a bipartisan “welfare reform” effort that replaced AFDC in 1996. The new TANF program drastically restructured the funding, the generosity of benefits, and the requirements for families to receive them (ASPE n.d.). As a result, TANF reaches far fewer families in poverty than its predecessor. Over the last several decades, both the share of eligible families that receive TANF benefits and the maximum value of those benefits have declined across the country, but this decline is most severe in Southern states with large Black populations. Eligible Black children are less likely to receive TANF benefits than white children, and Black families are more likely to live in states where benefits are the lowest (Shrivastava and Thompson 2022).

In 2021, only 20.7% of eligible families received TANF benefits, compared with 69.2% of families in 1997—the year TANF replaced AFDC (Crouse 2024). Recipiency rates of TANF benefits among eligible families in the South are often even lower. Among the 17 states where fewer than 10% of eligible families actually received TANF benefits in 2022 and 2023, 10 are in the South, and six Southern states provide TANF benefits to fewer than 5% of eligible families (see Figure A) (Bowden, Azevedo-McCaffrey, and Manansala 2025). These 17 states are home to 41% of the nation’s Black children, compared with only 28% of white children (Shrivastava and Thompson 2022).

Figure A

Southern states have also had the lowest maximum benefit levels throughout the history of AFDC and TANF (Floyd and Pavetti 2022). In recognition that benefit levels are far too low to keep up with the rising cost of living, 21 states and D.C. recently raised benefit levels, but only four of those states (plus D.C.) are in the South. As a result, Southern states, which already had the lowest benefits in the country, are now falling further behind. Among the 17 states where the maximum benefit remains less than 20% of the poverty line, 11 are in the South. And Southern states occupy seven of the 10 worst rankings for benefits as a share of the federal poverty level (see Figure B). In 2023, the maximum benefit for a family of three was $204 in Arkansas, compared with $1,243 in New Hampshire (Azevedo-McCaffrey and Aguas 2025).

Figure B

Additionally, because TANF is a block grant program, states can divert the funds to a broad range of uses beyond cash assistance for families with low incomes. TANF funds are misused in states across the country, but Southern states facing budget crises have shown a particular tendency to redirect TANF for other programs. For example, Louisiana spends much of its TANF grant on college scholarships, often for students whose families aren’t eligible for cash assistance. Georgia spends nearly half of its TANF funds on the child welfare system (Bergal 2020). And Mississippi illegally spent $77 million in TANF funds; $1.1 million went to former NFL player Brett Favre for speeches he never made and $5 million was used for a volleyball stadium at his alma mater (and where his daughter played volleyball) (Levenson and Gallagher 2022). In Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia, and Texas, the majority of TANF funds are neither spent on meeting families’ basic needs nor on connecting TANF recipients to work opportunities, the two main goals of the program (Azevedo-McCaffrey and Safawi 2022).

Lacking adequate public supports, Southern families face economic insecurity at high rates

Because the social safety net across the South was intentionally designed to be weak, families across the region face high poverty rates and struggle to reach and maintain a basic standard of economic security (Childers 2025). Economic insecurity can be measured across many dimensions, but this report focuses on food and housing insecurity since food and shelter are two of the most basic human needs.

The South has the highest rate of food insecurity

In 2023, 18 million households nationwide had limited or uncertain access to adequate food, and food insecurity was on the rise. Over a third (34.7%) of U.S. households with children headed by a single woman experienced food insecurity, and 7.2 million children lived in households where at least one child was food insecure (Rabbitt et al. 2024). Black households experienced food insecurity at three times the rate of white households, and Hispanic households experienced food insecurity at more than double the rate of white households (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2021).

The South has the highest rate of food insecurity of any U.S. region—in 2023, nearly 15% of Southern households were facing food insecurity. All U.S. states with food insecurity rates that are statistically significantly higher than the national average are in the South: Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas. Nearly every state with a higher-than-average rate of food insecurity is in the South, both prior to and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Rabbitt et al. 2024).

Renters and homeowners alike struggle to afford housing

Southerners are burdened by high housing costs and face high rates of evictions and foreclosures. Yet Southern lawmakers have failed to invest in affordable housing policies and protections for renters and homeowners. High-cost states like New York and California are commonly cited for having unaffordable housing. However, low incomes in the South have led to significant housing instability for renters across the region as costs rise and demand outpaces supply. Over the past decade, the states that have experienced the largest losses in low-rent units include Southern states that were previously considered affordable but have experienced increased rental demand, such as Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas. In three Southern states (Florida, Louisiana, and Texas), over half of renters are cost-burdened, with metro areas most heavily impacted (JCHS 2024a). Of the 10 metro areas with the highest share of cost burdened renters, six are in the South (five are in Florida, and one is in Texas) (JCHS 2024b).

Southern states have fewer tenant protections than other states and implemented fewer emergency protections for renters amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Nine Southern states received a rating of one star or less on the Eviction Lab’s COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard, which evaluated states’ strategies for ensuring stable housing for their residents. Arkansas, Georgia, and Oklahoma did not implement any statewide eviction moratorium during the pandemic (Eviction Lab 2021). States with tenant protections have lower eviction filing rates and reduced racial disparities in evictions than states with few or none (Gartland 2022). Southern cities have the highest eviction filing rates of any cities tracked, with Richmond, Virginia; Greenville, South Carolina; and Memphis, Tennessee, at the top of the list (Eviction Lab 2025).

Housing assistance programs are woefully inadequate

Housing assistance programs—like the Housing Choice Voucher program (the nation’s largest)—are not entitlements, meaning they are not available to all who are eligible for them. As a result, three in four people who are eligible for housing vouchers never receive them, and those who do obtain them face long waiting periods before receiving assistance. Of the nine states plus D.C. where wait times to receive vouchers exceed three years, six are in the South: Alabama, D.C., Maryland, Florida, Georgia, and Virginia. Two-thirds of households on waiting lists for housing assistance at large housing agencies are Black (Acosta and Gartland 2021).

Homeownership, an important wealth-building tool, is out of reach

Homeownership is most families’ primary source of wealth, and this is particularly true for Black and brown families. Yet homeownership is becoming increasingly inaccessible, due to the legacies of exclusionary housing policy, limited housing stock, and—more recently—the influence of real estate investment. In recent years, these investment companies have significantly increased their presence in the housing market, targeting areas of the country with fast population growth and weak tenant protections.

According to a 2025 report, private equity firms now own about 10% of all apartment units in the U.S., and more than half of private equity-owned units are located in five states, four of which are in the South (California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas). Among the 10 metropolitan areas with the largest number of private equity-owned units, 8 are in the South (Ash 2025). Black neighborhoods have been heavily targeted; nearly a third of home purchases in 2021 were to investors, compared with 12% in non-Black majority neighborhoods (Schaul and O’Connell 2022). Institutional investors tend to either flip homes or rent them out, decreasing the housing supply available to individual would-be home buyers while increasing rental costs for would-be renters (NLIHC 2022). Nine states, including North Carolina and Tennessee, have joined a federal civil lawsuit accusing the Texas tech company RealPage of illegally fixing rent prices to reduce competition and boost landlord profits. Florida, Georgia, and Texas, which also have large shares of private equity-owned apartment units, have not joined the lawsuit (U.S. et al. v. RealPage 2024).

Even for Southerners for whom homeownership is within reach, their access is more precarious compared with other regions. Foreclosure rates are higher in the South than any other region and have remained high in the wake of the pandemic. In 2024, four of the 10 states with the highest foreclosure rates were Southern states: Florida (3), South Carolina (5), Maryland (7), and Delaware (8) (Von Pohlmann 2024). Yet Southern lawmakers have done little to provide relief that would allow homeowners to stay in their homes. There are five states with no income-based policies to provide property tax affordability and they all are in the South—Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas (Davis and Samms 2023).

Underinvestment in health, child care, and transportation infrastructure block working families from full participation in the economy

Affordable and accessible health care, child care, and transportation infrastructure are essential public goods that support families’ well-being and workers’ ability to take and hold a job. Expanding health care access and affordability allows people to get necessary care to live and work. High-quality, accessible, and affordable child care enables parents to remain in the labor market while their children learn and grow. And transportation infrastructure—e.g., roads, bridges, and public transit systems—is critical to our physical and economic mobility, enabling people to get to work or school and buy goods and services that support the local economy. But just as they have opted to not invest in safety net programs, Southern lawmakers have similarly not prioritized investments in the region’s care and physical infrastructure—policy decisions that further exacerbate poverty and economic insecurity, deepen disparities by race/ethnicity and gender, and prevent Southern families from thriving.

Southern lawmakers have resisted opportunities to expand health care access through the Affordable Care Act

The 2010 federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is a comprehensive health care reform law designed to increase health insurance access and affordability, shift the focus of health care from treatment to prevention, and improve the efficiency of our health care system. Though the ACA is particularly beneficial to states with limited health care access and poor health conditions—as is the case across the South—Southern lawmakers led initial opposition to the ACA and have remained resistant to implementing the law.

In 2010, the state of Florida sued the federal government over the ACA, arguing that two key provisions in the law were unconstitutional. Among the 25 states across the country that joined Florida in the lawsuit, six were Southern states: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. Virginia filed its own lawsuit in opposition to the law. The rest of the South, except for Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, took no position—they did not oppose the law, but they also did not support it (KFF 2012). In 2018, 18 state attorneys general and two governors—10 of them from Southern states—sued over the law’s constitutionality again (CBPP 2021). Despite years of vocal opposition from Southern lawmakers, particularly in Texas and Florida, as well as President Trump’s promises to dismantle it, the ACA is increasingly popular in these states (Sanger-Katz 2023). In 2025, an all-time record of 24.2 million people signed up for an ACA plan, and enrollment has tripled since 2020 in six Southern states won by Trump in 2024, five of which had sued to block the implementation of the law (Ortaliza, Lo, and Cox 2025).

Failure to expand Medicaid has led to premature death for Southerners and hurt the South’s economy

Under the Affordable Care Act, states can expand Medicaid health benefits eligibility to nonelderly people with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, and the federal government will cover 90% or more of associated costs. Over 3.5 million fewer people would be uninsured if all states adopted Medicaid expansion, gains that would primarily benefit Black people, young adults, and women (Buettgens and Ramchandani 2022).

Though expanding Medicaid eligibility enjoys widespread public support and provides substantial health and economic benefits to states at very little cost, many Southern lawmakers have repeatedly rejected efforts to expand Medicaid in their states. Of the 10 states that have refused to expand Medicaid eligibility, seven are in the South: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas (KFF 2025). Non-expansion states nationwide and in the South have some of the highest uninsured rates in the country. Six of the 10 states nationwide with the highest uninsured rates are Southern states, and four of those Southern states have not expanded Medicaid. The District of Columbia is the only Southern jurisdiction with one of the 10 lowest uninsured rates (see Figure C).

Figure C

By refusing to accept the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, Southern lawmakers are denying tremendous welfare and economic benefits to their states. Medicaid expansion improves access to care, health outcomes, and financial security. When low-income adults have access to insurance, they are more likely to get regular preventive screenings, treatment for chronic conditions, and mental health and substance use disorder care.

Medicaid expansion has saved tens of thousands of lives and has also reduced racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage and access to care. In states that have expanded Medicaid, low-income adults have less medical debt and better access to credit, and are less likely to face eviction (Harker and Sharer 2024). Medicaid expansion also has implications for the broader economy of a state, including boosted federal revenues to the state and millions more in state and local taxes generated through increased economic activity (Ku and Brantley 2021). Despite arguments by critics that Medicaid expansion disincentivizes work, multiple studies have found little to no reduction in labor force participation because of expansion.4 Conversely, Medicaid is an important support for working people—particularly those with disabilities or chronic conditions—because it makes it easier for recipients to look for a job, work, and do a better job at work (Harker and Sharer 2024). Disabled adults are significantly more likely to be employed in expansion states versus non-expansion states and, as shown in Figure D, Southern states have some of the highest disability rates.

The health care sector is a major employer across the country and in the South. Twelve Southern states have a higher-than-average share of the population employed as health care practitioners and technicians,5 the majority of whom are employed in hospitals (BLS 2023). Hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid—especially those in rural areas—have fared better than those in non-expansion states, as increased insured rates lead to Medicaid covering care costs that would otherwise be uncompensated (Broaddus 2017).

The health and economic benefits of Medicaid expansion are numerous, but so are the costs of failure to expand. Between 2014 and 2017—just three years—an estimated nearly 12,000 older adults in the South died prematurely because of their states’ failure to expand Medicaid (Broaddus and Aron-Dine 2019). States that have not expanded Medicaid have experienced large increases in hospital closures, particularly in rural areas (Lindrooth et al. 2018). In the South, which is the most rural region of the country, a single rural hospital may be the only accessible point of health care for an entire community and its single largest employer. The closure of rural hospitals leads to increased transit times to access care—including for life-threatening emergencies—as well as losses in jobs and population that hinder the community’s ability to raise revenue and attract employers (Wishner et al. 2016). Of the 148 rural hospitals that have closed since 2011 (the year after the ACA was passed), just over half (76) of those closures occurred in the 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid, and 66 of those closures occurred in Southern non-expansion states. Nearly half of all Southern hospital closures occurred in just Tennessee and Texas (UNC Sheps 2023).

The failure to expand Medicaid has also led to worsening economic disparities. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, medical debt has become more concentrated in low-income communities in these states. While Southerners were more likely to have medical debt prior to the ACA, the failure to expand Medicaid widened debt disparities between the South and other regions. A recent nationwide analysis of credit scores found that the South had the lowest credit scores of any region, and that the share of residents with overdue medical debt was the strongest predictor of these scores (Van Dam 2023).

Refusal to invest in child care exacerbates economic insecurity for Southern families and providers alike

States in the South and across the country are facing a child care crisis, both for families who cannot afford the steep cost or for whom there are few available child care providers, as well as for early educators who are frequently paid poverty wages to provide this essential care. In most of the country, monthly child care is more expensive than housing, and in 38 states and D.C., child care costs more than public college tuition. Monthly infant care costs range from $572 in Mississippi to as high as $2,363 in D.C. Though costs are much lower in Mississippi than D.C., the impacts are felt similarly because household incomes are much lower in Mississippi. A median family with children in Mississippi would have to spend 10% of their income on child care, compared with 11.8% in D.C. (EPI 2025a).

During the pandemic, the federal government invested $24 billion into child care stabilization through the American Rescue Plan Act, an unprecedented lifeline to the child care sector that supported hundreds of thousands of providers and nearly 10 million children (ACF 2022). As these federal investments phased out, some states sought to fill the gap with state funding for child care (as in Vermont) or with tax credit expansions to pay for child care (as in Colorado, New York, and Utah) (Cohen 2023; Butkus 2024).

However, lawmakers in the South have deprioritized bills to address the child care crisis. In Florida, Kentucky, and West Virginia,6 bills to address child care affordability failed this legislative session— even though capping child care costs would boost labor forced participation, increasing these states’ economies by billions of dollars per year (EPI 2025a). And in Texas, despite a record state budget surplus of $32.7 billion in 2023 and advocacy by nearly three dozen child welfare organizations, state lawmakers declined to spend just $2.3 billion (less than a tenth of the surplus) to keep child care providers afloat amid the expiration of federal COVID-19 relief funds (Dey 2023). Instead, the state spent over a third of the surplus on new property tax cuts, which inherently benefit the wealthiest property owners.

Child care affordability is often measured based on the share of family income spent on a certain type of care—often infant care, since this is the expensive type of care. Though the share of families that can afford infant care is higher in the South than in other regions because infant care costs are generally lower, this affordability is based on median family income across all family types in aggregate, with most families with children comprising a two-parent married couple. This affordability calculation masks disparities in child care affordability between single- and two-parent households: As unaffordable as child care is for typical families, it is even more out of reach for single-parent households. In Southern states, an average of 38% of children live in a single-parent household—the highest nationwide (Annie E. Casey Foundation 2023). Single-parent households have a much higher cost burden, spending an average of three times as much for child care as married-couple families (35% of their income, compared with 10% for a married couple) (CCAoA 2025).

In the South, many states that pay the lowest minimum wages allowed by federal law, lag in workers’ rights, and refuse to expand Medicaid now also ban or severely limit abortion access (Banerjee 2022) while failing to take action to make child care affordable. For low-income women and women of color in states that have not prioritized health and economic security for children and families, forced childbirth and associated long-term, steep child-rearing costs will only exacerbate poor economic and health outcomes for both parents and their children, as well as racial and gender disparities in those outcomes.

Existing transportation infrastructure is inadequate for drivers, riders, and pedestrians

Safe, reliable, and affordable transportation is another huge factor affecting people’s access to good jobs (and the quality of their commute), access to essential goods and services, and overall well-being. It is also a major category of spending for U.S. households, accounting for 17% of annual household expenditures—more than every category except housing (BLS 2024a). At the same time, the U.S. transportation system faces major challenges, including high rates of injuries and fatalities, increasing roadway congestion, aging infrastructure, poor public transit access, and the need to reduce emissions in the face of climate change. These challenges have significant consequences for the U.S. population. Transportation incidents are the leading cause of death for U.S. workers, nearly 40% of major roads are in poor or mediocre conditions, transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and 45% of people in the U.S. have no access to public transportation (BLS 2024b; TRIP 2022; EPA 2022; APTA n.d.).

One reason U.S. roads are in such disrepair is because of insufficient state spending on road maintenance. When states do invest in transportation infrastructure, they often use federal funding to build new roads or expand existing ones instead of prioritizing road repair, leaving existing roads in poor condition to worsen and creating new unfunded maintenance liabilities. After the Obama administration directed $47 billion for transportation projects in 2009, the share of U.S. roads in poor condition increased as states—especially Southern states—used the money for continued road expansion instead of road repair. Of the eight states that spent at least 45% of highway capital funds for roadway expansion (Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, Texas, Utah), four are in the Southeast (Bellis, Osborne, and Davis 2019). This pattern has continued with the latest batch of federal infrastructure funding. The Biden administration’s 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) directed $643 billion for highways, roads, and bridges over five years—the largest ever federal infusion for transportation. Yet three years in, fully a quarter of the funds have been used to expand highways, which will create new emissions equivalent to the operation of 20 coal-fired power plants for a year. Of the 10 states spending the most IIJA funding on highway expansion, six are in the South. Meanwhile, of the 10 states spending the most IIJA funding on public transit and passenger rail per capita, only D.C. is in the South (Salerno 2024).

Public transit remains deprioritized in comparison with automobile transit, even as the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while expanding transit equity becomes more urgent. According to the National Resources Defense Council, of the 10 states doing the least to improve equity and climate outcomes in transportation, six are in the South, and the Southeast ranked lowest of any region on its commitments to these goals (Henningson 2025). In 2024, Georgia’s governor, acknowledging “record job and population growth” in the state, announced a $1.5 billion transportation funding plan to improve and expand roads, highways, bridges, and freight infrastructure, but did not dedicate any funding to public transit projects (Kemp 2024). In fact, Georgia’s MARTA system is the only transportation agency in operation that has never received any state funds (King 2023).

There are also substantial disparities in transportation access based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and ability across the country. Because of racial and ethnic income and wealth disparities, workers of color are less likely to own a car and be more dependent on public transit (Austin 2017). Yet due to legacies of segregation, white flight and suburbanization, and corresponding disinvestment in urban transit in favor of the federal highway system, Black workers, other workers of color, and low-income people face worse transit quality and longer commute times (Sánchez, Stolz, and Ma 2003; National Equity Atlas 2019). They are also more likely to be killed in traffic accidents while walking, cycling, or riding in a car (Raifman and Choma 2022).

How historic racism shaped Atlanta’s transit network

In the mid-20th century, in metropolitan areas across the country, white suburban homeowners and their allies in elected office and the business community lobbied for public transit systems that prioritized their interests at every turn while denying access to Black communities in the urban core. The development of highways and the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) in Atlanta, Georgia, is a case in point. In the post-WWII era, white business elites who increasingly lived outside the city but sought to remain connected to the urban core aggressively pursued highway development and other land use policy that facilitated this movement, while systematically segregating the city and displacing Black communities. Among the approximately 70,000 people displaced because of “urban renewal” (demolition) of residential urban areas to make way for interstate construction in Atlanta, 95% were Black (Keating 2001).

In the early 1960s, in order to further their business interests and boost downtown land values, white elites pursued the development of light rail transit despite its higher cost and more limited effectiveness than bus transit, which lacked “social status.” Initial proposals for MARTA included more rail lines in white communities than in Black communities, but advocacy by Black community members led to the development of a more equitable transit system. Instead of sharing transportation with a majority low-income Black ridership, white people simply declined to take public transportation and drove their cars instead, leading to significant underfunding that restricted MARTA’s expansion. Over the next three decades, the Atlanta metro region population grew significantly alongside a wave of corporate job growth in the suburbs to the detriment of jobs in the city and along racial lines (the regions that gained the most jobs were majority-white). By 2000, the metro region population had grown by 128% while the city of Atlanta’s population declined by 16%. The movement of jobs from the mostly Black urban core to the mostly white suburbs and the failure to develop a system of transit to allow for transit between them both prevented Black Atlantans from accessing economic opportunities afforded to whites and led to traffic- and transportation-related challenges that have only worsened as the region has continued to grow (PSE 2017).

The lack of affordable, accessible public transportation is also unevenly distributed across disability status and urbanicity. Across the country, disabled adults of all racial and ethnic groups are twice as likely as non-disabled adults to face inadequate transportation access, and over a half a million disabled people are unable to leave their homes as a result (Urban Institute 2020). Of the 10 states with the highest share of adults with a disability, eight are Southern states (see Figure D).

Figure D

Additionally, though public transportation is more commonly discussed in the context of cities, access to transportation in rural areas poses unique challenges that are becoming more urgent as the population ages and demand for accessible public transit grows. The East South Central Census division encompassing Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee is the least urban area in the country (U.S. Census 2022). And in nine Southern states, the share of rural residents with no access to intercity transportation—rail, bus, or airline—exceeded the national average (14.6%). While some Southern states have increased access to intercity transportation between 2006 and 2021, seven Southern states have seen declines in access over the same period, with double digit declines in Oklahoma (11.7 percentage points) and Arkansas (18.5 percentage points). Populations in rural areas without access to intercity transportation are more likely than those in more connected rural areas to be over the age of 65, low-income, in poverty, unemployed, and carless. With no car and no public transit, many rural residents in the South and around the country are effectively denied access to employment, education, and other pathways to greater economic security, and older adults are forced to rely on the kindness of others to meet their basic needs (BTS 2023).

The failure to invest in affordable health care, accessible high-quality child care, and convenient climate-friendly transportation systems is shortsighted and has worsened quality of life across the South. When workers and families are not able to maintain their health and well-being and access services that enable them to fully participate in civic, social, and economic institutions, we all suffer.

Southern lawmakers weaponize the poor outcomes of their own public revenue failures to fuel a vicious cycle of bad policies

The Southern economic development model is characterized by regressive tax and budget systems, with revenue programs that extract a larger share of income from families with the least ability to pay and often deliver targeted benefits specifically to businesses and the wealthy. These policies weaken the labor market power and jobs options for low-income families, contribute to income and wealth inequality, and fail to raise adequate revenue for public goods and services. Southern lawmakers have then frequently responded to revenue shortfalls with additional regressive forms of revenue generation like fees and fines, while providing tax cuts and economic development subsidies to businesses with the claim that such benefits to businesses will “trickle down” to the public at large. They also use the failure of such policies as a pretext to shrink the public sector and outsource core government functions to private companies motivated by profit as opposed to effectiveness or equity.

Regressive tax and budget policies exacerbate inequality

Taxes are the primary means by which state and local governments raise revenue to pay for essential goods and services, such as education, health care, infrastructure, and public safety. However, the Southern model’s tax policies have resulted in chronic underfunding that exacerbates income and wealth disparities by race and class and keeps living standards inadequate for many residents.

Anti-tax sentiment in the South is a direct legacy of slavery. Because enslaved people were treated (and taxed) as property, enslavers saw property taxation as an existential threat and worried that non-enslaving majorities would use taxation to weaken—and eventually abolish—the institution of slavery. Enslavers went to great lengths to preserve their power through anti-democratic means, including manipulating the rules of the legislative process, ensuring weak government, and limiting the constitutionality of taxation (Einhorn 2006). During Reconstruction, racist former enslavers rebranded themselves as “concerned taxpayers” to forge an alliance with small white farmers, sow racial division, and justify racist violence (Das 2022). Through the mid-19th century, taxes levied on enslaved people and the wealth they created for white enslavers through their forced labor were the single largest revenue source for state governments (between 30–60%) and were paid mostly by large landowning enslavers. When slavery was abolished, white Southerners, particularly small non-enslaving landowners, vehemently opposed all efforts to replace “slave tax” revenue with other tax measures (Lyman 2017).

In the mid-1880s, Southern states relied heavily on corporate income taxes—a legacy of slavery-era opposition to property taxes that was nonetheless fairly progressive in the sense that corporations generally have a higher ability to pay. However, amid the economic expansion following WWII, Southern states slashed corporate tax rates to lure businesses to the region and enacted sales taxes to fill the revenue gap (Das 2022). This tax policy agenda is being reenacted in many Southern states under the modern Southern economic development model. Rather than being described as “anti-tax” this model is better characterized anti-tax for the wealthy and corporations. Since corporate taxes are paid primarily by wealthy shareholders and sales taxes are paid primarily by low- and middle-income households, this shift in the tax burden amounts to an upward redistribution of income that persists in the modern South and hinders the region from raising adequate revenue.

Today, state taxation structures in Southern states are some of the most regressive in the nation. A tax is “regressive” when it forces people with lower incomes to pay a higher share of their income in taxes than people with higher incomes. The states with the most regressive tax systems typically rely heavily on sales and excise taxes (extremely regressive) and property taxes (somewhat regressive). States with regressive tax systems also typically lack a graduated personal income tax or impose low corporate income taxes. Of the 10 states with the most regressive tax structures, half are Southern states: Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas (ITEP 2024). In 11 Southern states, the poorest 20% of residents pay more in sales taxes alone than the top 1% of residents pay in all state and local taxes combined (see Figure E and Appendix Table 1).

Figure E

Regressive taxes are not only inequitable from an economic justice perspective but also as a matter of racial and gender justice. Since Black, Hispanic, and women workers are more likely to earn low wages, they disproportionately bear the brunt of tax structures that tax the lowest paid workers the most. Tennessee, a state that also lacks a personal income tax and relies heavily on sales and excise taxes, is a case in point. In Tennessee, Black and Hispanic families—whose median household incomes are 19% less than the statewide median of all families—are taxed at a rate higher than the statewide average, while white and Asian families—with median household incomes 22% above the statewide average—are taxed at a lower-than-average rate.7 Meanwhile, in the more progressive taxation state of Minnesota, Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous families are taxed at below-average rates, in line with their relatively lower family incomes. Regressive taxes exacerbate racial, ethnic, and gender income inequality while progressive taxes can counteract these disparities (Davis and Guzman 2021).

Yet instead of addressing their inequitable tax structures, the South has led the charge of further increasing tax regressivity in recent years. Of the eight states that have moved toward regressive state tax structures since 2018, five are in the South: Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, and West Virginia (ITEP 2024). In four of these states, lawmakers have expressed interest in fully eliminating the personal income tax (Davis and Trinidad 2023). In her inaugural address, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders committed to “eventually wipe the income tax off the books” and an overall agenda of deregulation (Sanders 2023), declaring:

“We will no longer surrender our jobs, our talent, our businesses and our economic might to states like Tennessee and Texas that have no income tax. Arkansas is going to fight for every job – and let me be clear, Arkansas is going to win. … s long as I am your governor, the meddling hand of big government creeping down from Washington DC will be stopped cold at the Mississippi River. We will get the over-regulating, micromanaging, bureaucratic tyrants off of your backs, out of your wallets and out of your lives.”

In 2024, Sanders signed into law a bill to reduce tax rates on the wealthy and corporations, which will cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars per year (DeMillo 2024). In 2025, Mississippi lawmakers passed a bill to reduce the state’s personal income tax from 4 to 3%, and eventually eliminate it entirely, replacing it with an increased regressive tax on gasoline (Vance, Goldberg, and Pender 2025). Also this year, Kentucky passed a similar income tax elimination bill (Sonka 2025) and Florida’s governor proposed eliminating all property taxes (Perry 2025). Florida already has the most regressive state tax system in the country, in part because it has no personal income tax and relies heavily on sales and excise taxes, the most regressive type of tax. But property taxes account for over 40% of the state’s total tax revenue (ITEP 2024), so unless that lost revenue is made up through progressive means—which the governor has ruled out—eliminating property taxes will be disastrous for the state’s budget and could lead to a complete dismantling of the public school system (which gets around half its funding from property taxes) (Sczesny 2025). Of course, for Florida’s governor—who has been on a years-long crusade against public schools (Strauss 2022) and recently applauded President Trump’s move to shutter the federal Department of Education (DeSantis 2025b)—dismantling the state’s education system may, in fact, be the goal.

Inadequate revenue generation leads to low public spending, exacerbates racial disparities

Due to their high poverty rates, regressive tax structures, and failure to tax corporate income, Southern states collect little revenue per capita compared with other states (TPC 2023a) and are highly dependent on federal government spending to meet their residents’ basic needs. Southern states receive more federal government spending than they contribute to the federal government income and business taxes. Because Southern states have lower-than-average income levels and higher poverty rates, these states receive higher-than-average federal contributions to social safety net programs like Medicaid, SNAP, and TANF. Of the 10 states that rely on federal government funding the most, seven are Southern states. In Florida, where the governor has boasted about saving taxpayers’ money by returning federal funds (DeSantis 2025a), the state accepted nearly $37 billion more in federal funds than it paid in the form of taxes, equivalent to about a third of the state’s budget for fiscal year 2026 (see Figure F).

Figure F

As a result of chronic revenue shortfalls, state governments in the South spend less per capita overall than other regions, as well as less per capita on primary and secondary education and public welfare (TPC 2023a; TPC 2023b). Lawmakers in these states justify low spending on public welfare and programs that benefit all low- and middle-income workers by weaponizing ideological narratives about deservedness that are steeped in racism and misogyny and sowing racial and class division (Black and Sprague 2017). In reality, public revenue shortfalls harm everyone because the goods and services provided by the public sector are used by everyone. And when states are unable to raise adequate revenue, rather than making up the shortfall by seeking additional revenue through progressive taxation or clawing back subsidies provided to private businesses, the first budget items to be defunded are frequently public-sector jobs and the services public-sector workers provide.

These dynamics were further exacerbated by the pandemic. Revenue-starved states received millions of dollars in federally provided fiscal recovery funds as part of the package of federal COVID-19 response bills. Yet instead of using those funds for necessary public services, nine Southern states exploited resulting temporary budget surpluses to enact costly permanent personal or corporate income tax cuts.8 In North Carolina and West Virginia, the cost of the cuts exceeds 10% of total general fund revenue (Tharpe 2023). In Texas, nearly half of the $15.8 billion in fiscal recovery funds the state received were used to shield businesses from future unemployment insurance tax increases (Villanueva 2022).

Southern states rely heavily on non-tax revenue sources like fees and fines, which exacerbate income and racial inequality

The failure of states and localities to raise adequate revenue equitably imposes a double penalty on low-income communities of color. Lawmakers impose regressive tax systems that prioritize the wealthy and corporations, raise insufficient revenue, and then use budget shortalls to justify deep cuts to the public sector and social programs. At the same time, lawmakers in many Southern states simultaneously impose regressive fines and fees on these same communities to offset budget gaps. States and localities across the country, particularly rural and low-income communities, are heavily dependent on fees and fines imposed for minor violations or as alternatives to incarceration. Of the 10 states that rely most heavily on non-tax revenue (including fees, fines, and other surcharges) to fund the public sector, five are Southern states. A third or more of these states’ revenue comes from non-tax sources (ITEP 2024).9

There are racial disparities in every aspect of the criminal legal system, and the assessment and collection of fines and fees is no exception. Black people are more likely to be subject to traffic stops (Pierson et al. 2020)—the most common way people encounter police in the U.S.—and Black communities are also targeted with higher rates of fine and fee enforcement (USCCR 2019). Cities with larger Black populations (most of which are in the South) rely more heavily on fine and fee revenue. Southern states—particularly states with a history of convict leasing10—impose more fees and more mandatory (as opposed to discretionary) fees than any other region (Zvonkovich, Haynes, and Ruback 2022). Though lawmakers in many Southern states have introduced proposals to curb regressive fines and fees, such proposals have made little progress in the states most reliant on them (FFJC 2024).

The expectation that public agencies—charged with serving the public good—seek revenue from fines and fees in order to fund the agencies that employ them represents a profound conflict of interest. Indeed, all six of the small cities across the country that rely on fines and fees for at least half their revenue (five of which are in the South) spent at least a third of their budgets on law enforcement activities in 2017 (TPC 2024). The use of fees and fines to fund government or even new law enforcement activities can undermine public trust in institutions and their perceived legitimacy as agents of the public good (Boddupalli and Mucciolo 2022).

On top of the enduring harms that fines and fees impose on adults and youth of color and their corrosive influence on democracy, fines and fees are an inefficient method of raising public revenue. A study of 10 counties across Texas, Florida, and New Mexico found that these jurisdictions spent an average of 41 cents for every dollar collected from in-court and jail costs alone, and billions of dollars go uncollected every year because individuals are unable to pay (Menendez et al. 2019).

Southern dependency on fine and fee revenue deepens poverty and racial inequality, encourages expansion of the criminal legal system, and limits localities’ ability to invest in public services that benefit everyone. While Southern states are structuring their public financing in regressive and harmful ways, they are simultaneously giving enormous tax breaks and public subsidies to corporations. As the next section explains, the one area where Southern governments are not stingy with public dollars is in providing supports to business.

Economic development incentives fail to produce community benefits and drain limited public revenue to the private sector

Modern urban governance in the United States is so dominated by entrepreneurialism—a stance that prioritizes economic development and public investment into projects that mainly benefit the private sector—that this mode of governance may feel natural or unassailable. However, entrepreneurialism is a relatively new advancement, one that emerged in the early 1970s in response to a combination of deindustrialization, fiscal austerity, and the rise of neoconservatism and privatization (Harvey 1989). Whereas “managerialism” (which primarily focused on the local provision of services for the benefit of residents) was once commonplace, state and local tax and budget policy today is increasingly tilted in favor of the private sector, while benefits to the public are second-order and, in some cases, nonexistent.

Entrepreneurialism often takes the form of corporate subsidies: economic development grants, reimbursements, loans, tax abatements, infrastructure development, and other forms of financial assistance to businesses by federal, state, or local governments. Although not unique to the South, the use of publicly funded corporate subsidies is particularly harmful to Southern states that have long faced revenue shortfalls. These tax abatements (which allow a selected business to pay lower taxes or eliminate its tax obligation entirely) and other subsidies (such as direct cash grants to companies) are taxpayer funded and directly reduce the state’s ability to fund public services.

Working families pay their fair share (or more) in state and local taxes, with the expectation of public investment in essential public goods and services like schools, health care, food assistance, transit, and affordable housing. Instead, this public revenue is given to corporations in the form of subsidies or tax breaks. In exchange for corporate tax benefits, firms that receive such awards often make vague promises about projects’ benefits for local communities. However, these promises are notoriously difficult to assess. Southern states have particularly low disclosure requirements—Alabama and Georgia have no meaningful disclosure at all. Nine Southern states have below-average disclosure scores according to public-spending watchdog group Good Jobs First (Tarczynska, Wen, and Furtado 2022). As a result, it is extremely difficult for researchers, advocates, and the taxpayers themselves to investigate whether corporate incentives serve the public good.

In 2022, a banner year for corporate subsidy packages to individual companies exceeding $100 million, nearly half (14 out of 30) of these “megadeals” were awarded to businesses in Southern states (GJF 2022a). These megadeals—which include but are not limited to tax breaks—amounted to at least $10.7 billion dollars in taxpayer funds given by these state and local governments to large corporations (see Figure G). Of the nine companies that received megadeals worth $1 billion or more in 2022 (the costliest year on record for megadeals), four of those deals were provided by Southern states (Tarczynska 2022). And three of the four megadeals in the South went to the auto manufacturing industry, which has grown significantly in the South over the past two decades as businesses seek to take advantage of the South’s weak regulatory environment, anti-worker policies, and use of public revenue to attract private investment. But these incentives have not produced the family-sustaining, union jobs historically associated with the Midwestern auto industry. Instead, faced with low wages, unsafe workplaces, and the anti-union sentiment inherent to the Southern economic development model, Southern autoworkers must fight tirelessly just to achieve any benefits from the public subsidy afforded their employers (Childers 2024d).

Figure G

In recent years, Southern states have given away billions of dollars in public revenue in the form of direct subsidies and tax breaks to corporations. This is revenue the state would have raised if it taxed corporations regularly, as opposed to preferentially. For example, in Tennessee, forgone revenue between fiscal years 2017 and 2021 exceeded the state’s total budget for transportation in 2021 by over $100 million (GJF 2022c). In the city of Memphis, where public pensions are chronically underfunded, public dollars spent on tax abatements and subsidies could have fully funded the city’s pension obligations for every year between 2009 and 2012 (Cafcas et al. 2014). In Louisiana, the state lost more due to economic development tax breaks than it spent on transportation, corrections, youth development, and agriculture combined in 2021 (GJF 2022b).

The impact of tax abatements on public education is particularly extreme because property taxes (which are a common target of economic development tax breaks) are the single largest source of funding for public schools across the country. In 2019, of the 10 school districts that lost the most revenue to tax abatements, six were in Southern states—three in South Carolina, two in Louisiana, and one in Texas (Wen, Furtado, and LeRoy 2021).

Louisiana’s five most populous school districts lost nearly $40 million to economic development tax breaks in 2021. And Texas, which lost $1.23 billion to corporate subsidies in 2022, is home to 49 of the 52 school districts nationwide where per-pupil losses exceed $1000 per year. These revenue shortfalls disproportionately harm low-income, Hispanic, and Black students whose school districts are more likely to hand out costly tax abatements (Wen, Furtado, and LeRoy 2021).

To hold companies accountable to the expectation that publicly funded projects benefit the public, advocates for workers and communities have leveraged tools like Project Labor Agreements (PLAs) and Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs). A PLA is a pre-hire collective bargaining agreement negotiated among multiple contractors, unions, and project owners that establishes the terms and conditions of employment that will apply to a specific construction project, and CBAs are PLAs that also involve community stakeholders and may include community-focused benefits beyond any employment requirements.

Unfortunately, most Southern states have provisions in state law that block local governments from abiding by PLAs, resulting in economic development projects that often do not support local workers and communities. In the past two years, Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee have signed measures into law that bar companies from receiving state economic development funds if they voluntarily recognize unions, and Tennessee enacted a bill that bars companies from receiving state economic development funds if they enter into a community benefits agreement. These policies reflect an economic model that seeks to enrich business interests at the expense of workers and communities, in this case using public money to disempower workers and block communities from benefiting from economic development (Sherer 2024; Tennessee General Assembly 2025).

Privatization is offered as the cure for hollowed-out public services

From public schools to the social safety net, Southern lawmakers have led the charge to privatize public services and replace them with for-profit alternatives that are often worse, more expensive, and unconcerned with values like equity and fairness. Privatization is a central tenet of the Southern economic development model because it prioritizes the interests of the wealthy (who are overwhelming white) and businesses at the expense of working people, low-income Black communities and communities of color, and public-sector workers. The public sector has historically been a source of good union jobs and a pathway to the middle class—particularly for Black workers (Morrissey 2020). Thus, privatization serves the Southern model both in its service of business interests at the expense of workers and in its agenda to limit the role of the public sector in regulating corporate power and serving the public good.

Private school vouchers are a modern-day effort to reinstitute segregation, whether by race, class, or religion

The privatization of public schools in the United States is rooted in anti-Black racism and efforts to resist desegregation. In the decade prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling mandating school segregation, private school enrollment increased 43% in the South. By the end of 1956, six Southern states had passed constitutional amendments permitting the state to divert public funds to private schools (Suitts 2019), and by 1965 there were nearly one million private school students in the South. While public schools desegregated slowly over the 1960s and 1970s, private school enrollment grew, particularly in the South. By the early 1980s, the South accounted for nearly a quarter of private school enrollment nationwide, and most students attended schools where 90% or more of students were white (SEF n.d.).

Though voucher advocates have claimed that such programs improve educational outcomes for low-income Black and Hispanic children, an extensive body of research finds that vouchers do not improve educational outcomes and more likely worsen them (Mast 2023). Voucher programs divert public funds to private schools (predominantly religious schools) where white students are overrepresented—these margins are greatest in the South (Suitts 2019). Private school voucher programs allow primarily white wealthy families, many of whom are already sending their children to private schools, to offset these costs with public dollars that are intended for public schools. In many states with private school voucher programs, most voucher recipients attend religious schools, amounting to billions of taxpayer dollars being used to subsidize religious education.

This subsidization of religious education parallels a simultaneous effort—popular in Southern states—to implement government-sponsored, often conservative religious ideology in the public school system (Meckler and Boorstein 2024). Oklahoma approved an application for a publicly-funded Catholic charter school back in 2023 (Perez Jr. and Gerstein 2025). The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which recently affirmed the decision of the Oklahoma Supreme Court blocking the use of public funds for the nation’s first religious public charter school. However, given an evenly split vote, the ruling lacks precedential force (Saiger 2025), leaving the door open for states to continue eroding the separation between church and state through the use of government funds for religious education. A decision approving of the direct use of government funds to pay for religious education would amount to a significant erosion of the separation between church and state.

Today, 31 states and D.C. have some sort of voucher program in place that diverts public funds to private schools (Wething 2024). Though only 13 of those states (plus D.C.) are in the South, the South has some of the most established and expensive programs, spending hundreds of millions—or, in the case of Florida, billions—of public dollars to subsidize private schools (Dollard and McKillip 2025). In 2025 alone, public education advocates tracked voucher expansion bills in at least 22 states (PFPS 2025). After years of opposition, Texas passed a private school voucher program that will cost the state billions over the next few years (Edison 2025), and South Carolina reinstated a private school tuition subsidy program that had been ruled unconstitutional (Kesler 2025).

Efforts to implement and expand voucher programs in states across the country—through private school vouchers, Education Savings Accounts, and tax credits—are key to the relentless and enduring campaign to defund and privatize public education, a movement that also includes manufacturing mistrust in public schools and targeting educators and their unions (Mast 2023). The result, by design, is the defunding of the public school system, which in turn strengthens the arguments in favor of privatization as a solution to an ailing public school system. The Trump administration’s move in early 2025 to shutter the Department of Education is the culmination of the decades-long campaign to abolish public education, a campaign that began in the South and has been spearheaded by Southern lawmakers and billionaire-backed right-wing groups (Sullivan 2025; Blake 2024; Gott 2018).

Southern lawmakers have long sought to privatize our most important and popular social programs

Republicans in Congress and at many levels of government have long sought to privatize even the most overwhelmingly popular federal social programs, particularly Medicare and Social Security. Social Security is the largest anti-poverty program in the country and is the most important source of income for seniors; without it, over 25 million more people would be in poverty (Banerjee and Zipperer 2022). More than 64 million people rely on Medicare coverage for their health insurance coverage (CMS 2022). From Texas President George W. Bush’s plan to privatize Social Security in 2005, to Florida Senator Rick Scott’s plan to phase out all federal social programs in 2022 (Everett 2022), Southern Republicans have consistently been among the most vocal supporters of privatization (Scott 2022).

Privatization is often touted as a solution to bureaucratic red tape or cutting “wasteful” government spending, but in practice, it can mean cutting the experienced public workforce who administer complicated government programs. This can result in prolonged delays, more people wrongly denied benefits, and ultimately worse outcomes for people who need the benefits most. For instance, when Texas outsourced its SNAP eligibility determinations to a for-profit company in 2006, thousands of people were unable to apply or were given incorrect information and many were wrongly denied benefits. Public-sector staff were then forced to fix mistakes, and eligible SNAP participants were subject to long delays to receive benefits (Sanders and Mast 2024).