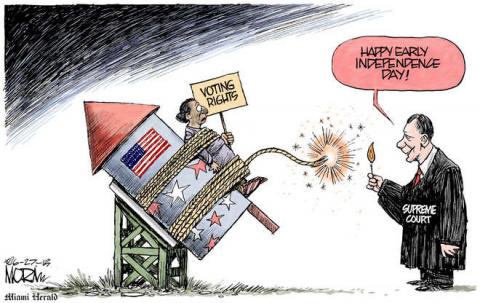

The Supreme Court's decision to strike down a key piece of the Voting Rights Act this week was met with frustration and outrage by civil rights and voting advocates across the South. What exactly will it mean for Southern politics?

The ultimate impact of the court's decision will be to weaken the voting strength of African Americans, Latinos and others that make up the rising Southern electorate. At the very moment the demographics of Southern voters are rapidly changing -- and posing a challenge to conservative rule in many parts of the South -- the court's decision clears the way for states to change election laws in ways that limit voting access for millions of voters, disproportionately those who lean progressive.

The court struck down Section 4 of the act, which created the formula governing which areas of the country needed federal approval -- "preclearance," outlined in Section 5 -- before making major changes to their election laws. The formula, which covers all or part of nine Southern states, was reaffirmed by Congress in 2006. In testimony over the law's reauthorization, it was revealed that at that point the act had led to the blocking of more than 2,400 discriminatory voting changes proposed by state and local election officials.

In many of these states, Sections 4 and 5 of the act were the only tools at the disposal of voting rights advocates to prevent election law changes from being implemented that would restrict voting access to African Americans, Latinos and other historically disenfranchised voters.

With that barrier removed, Southern leaders have virtually unobstructed ability to push through sweeping changes that will affect the voting access and electoral power of millions of voters, including:

PHOTO ID: As ColorLines reported, within hours of the Supreme Court's decision Republicans in Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas vowed to implement strict voter photo ID requirements, which had been held up in court -- or faced tough review in the future -- due to Section 4 and 5's preclearance requirements.

EARLY VOTING AND SUNDAY VOTING: The Justice Department was inconsistent in its willingness to intervene on state laws about the number of early voting days and Sunday voting. For example, in 2012 they dropped their Section 5 objection to Florida's law limiting both. But the absence of any possibility of Section 5 blocking such changes may embolden lawmakers to push these laws more aggressively in states like North Carolina, where Republicans have pledged to introduce such legislation.

REDISTRICTING: The Supreme Court ruling also clears the way for Texas' redistricting plan, which had been blocked by the Department of Justice because of its failure to ensure adequate representation for Latino voters. It may also impact the fate of how lines are drawn in other states where redistricting is still up in the air, including Mississippi and North Carolina.

The demise of Sections 4 and 5 creates the potential for a vicious cycle of disenfranchisement in Southern states: Without the threat of federal intervention, lawmakers can push more lopsided voting laws, which will further skew the electorate in support of conservative lawmakers who don't reflect the changing population of Southern states. These lawmakers will then have more political muscle to implement or expand new voting restrictions, further exacerbating the disconnect between Southern voters and those who represent them in office.

How can Southern voters break this cycle? Left standing after the court's decision is Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which allows for those who have been disenfranchised to go to court. But it's an expensive and time-consuming strategy -- for both plaintiffs and defendants -- and can only be pursued once the damage is already done.

Other civil rights advocates are looking to national strategies such as pressuring Congress to revise the Voting Rights Act in a way that could pass Supreme Court scrutiny, or moving towards changes to federal election law -- like automatic, universal voter registration -- that would make elections more equitable and blunt the discriminatory impact of losing parts of the Voting Rights Act.

But those are all long-term strategies that, in a divided Congress grappling with many other big issues, face long odds. This means that the battle over voting rights in the South in the coming months and even years will largely be fought in the states, one bill at a time. Groups will be mobilizing to ensure voters have proper IDs and get to the remaining early voting days.

State courts will also become critical arenas in the defense of voting rights, making issue of judicial elections -- and the big money that flows into judicial campaigns -- all the more important. In North Carolina, seven state appellate and Supreme Court seats will come up for election in 2014. In the wake of Republican mega-donor Art Pope's successful campaign to eliminate the state's judicial "clean elections" reform, court races will be magnets for special interests seeking to spend money to influence their outcome.

But the battle over voting rights will also be at the level of perception: What kind of South do we want? The Voting Rights Act was a key engine of Southern progress, leveling the political playing field but also improving the South's image and economic success. As historian Gavin Wright notes, the political gains from the act translated into money for roads and city services in African-American communities in the South. It also boosted political support for schools, lifting the economic fortunes of Southern communities of all races.

If conservatives push too hard and too fast to reverse the Voting Rights Act's gains, it may help tilt the electorate in ways that helps score some quick political victories. But it also connects them to an Old South legacy that could backfire. In the short term, these attacks could be a spark to mobilize African-American, Asian-American, Latino, young and urban voters to head to the polls in 2014. In the long run, though, they risk alienating the emerging Southern electorate at the very moment its gaining critical mass and the power to shape the South's political future.

As political observer Jamelle Bouie argued in The Daily Beast:

Republicans have an important choice to make. They can ... secure short-term gain at the cost of their long-term prospects, or they can wait, seize this new opportunity for outreach, and in doing so move their party into line with America's more diverse future.

[Chris Kromm, Executive Director; Publisher, Facing South and Southern Exposure, joined the staff of the Institute and Southern Exposure in May 1997. From 1997 to 2000, he was the editor of Southern Exposure magazine. He was appointed Executive Director in 2000. He has appeared on over 250 TV and radio broadcasts including American Public Media's "Marketplace," CNN "Live," C-SPAN, Democracy Now, Mississippi Public Radio, NPR's "All Things Considered," Pacifica Radio. Kromm's writing and reporting have also appeared in The Durham Herald-Sun, The Hill, The Huffington Post, The Independent Weekly, The Journal of Environmental Education, The Nation, The Raleigh News & Observer, Salon and other publications. Chris is the author or co-author of 12 Institute reports, most recently Counting in a Crisis (March/April 2010).]

Spread the word