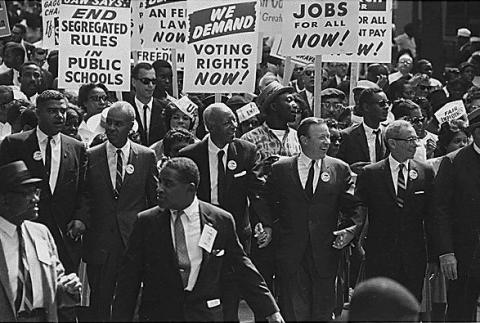

Fifty years ago, America witnessed the gigantic March on Washington when 250,000 people, the largest gathering of its kind, heard many petition the government for change. Speakers included 34-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. who proclaimed his dream to overcome history.

As noted by cultural icon Harry Belafonte, the time had come to make those comfortable with oppression uncomfortable. The march, propelled by Sam Cooke's classic piece titled "A Change is Gonna Come," coincided with President John F. Kennedy's plan to submit to Congress a landmark civil rights bill.

This is a year for commemorations, such as the 150th anniversary of West Virginia statehood and President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. It is more than ironic that it is also when the U.S. Supreme court gutted the Voting Rights Act, a key component of the movement for human rights, respect, and fairness hailed as breakthrough legislation a half century ago.

Few may understand that landmark legislation is seldom permanent. Upon passage, opponents gather to plan its eventual challenge and demise. Examples are many.

Amid the Depression, an outcry for fairness by veterans and working people resulted in a sea of social, employment and economic legislation including the National Industrial Recovery Act. Nicknamed the "Blue Eagle Act," the NIRA did many things including Section 7 that provided workers the right to chose a union to represent them in their quest for better wages, hours and working conditions in the private sector.

Within only a few years, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the act. In turn, sections were salvaged and passed as the National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act. Again, this act was weakened a decade later by the Taft-Hartley Act, which included Section 14b that permitted states to pass anti-union legislation designed to entice a jobs shift from the industrial and unionized northern states.

Another example is black lung legislation. Propelled by events in West Virginia including the march on the state capital by the Disabled Miners and Widows Association and the Black Lung Movement, along with continuing mining disasters such as Mannington, the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act was passed in 1969.

As part of that movement, activists including Ken Hechler, Arnold Miller, Helen Powell, Craig Robinson -- along with West Virginia doctors I.E. Buff, Hawey Wells and Donald Rasmussen -- were instrumental in drafting black lung legislation that made the disease recognized as a work-related outcome of mining coal.

Again, forces gathered to fight the legislation, resulting in one bill after another that diluted the ability of victims to obtain compensation. To this day, local efforts by law students at Washington and Lee University, attorney John Cline, and vigilant efforts by Black Lung Association chapters continue to challenge regulations designed to deny and delay benefits.

Furthermore, the black lung battle overlaps with coal dust exposure rules. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, between 1996 and 2005 nearly 10,000 miners died of black lung, 1,800 in West Virginia. Many more miners are significantly handicapped. Currently, the legal limits of permissible coal dust in the mines continues to be fought as the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, bowing to industry objections, recently announced another delay in implementing rules initially announced three years ago.

Landmark legislation is often designed to pacify and defuse social outrage and unrest. While at the time, many feel that they have made a difference for change and a step forward, euphoria lasts only until die-hard opponents seek an opportunity for a successful challenge and reversal.

Perhaps the next example will be the Affordable Care Act. While the Supreme Court ruled recently that the act could go forward, it is only a matter of time before a challenge of a particular provision will be before the court again. The prevalence of 5-4 decisions means that every decision is tenuous and vulnerable.

This problem is not new. President Franklin Roosevelt had the same challenge in the 1930s when he threatened to pack the court after a rash of 5-4 decisions that gutted New Deal efforts, including the Blue Eagle Act, to deal with the economic depression that gripped the nation.

The challenge facing any piece of major legislation goes beyond the movement necessary for passage. There must be recognition of the need for vigilance which requires dedicated education and expectation that guaranteed fairness for all is a human right that must permanently prevail.

[John P. David, Ph.D. is Emeritus Professor of Economics/Labor at West Virginia University Institute of Technology; and is Director of the Southern Appalachian Labor School. He is a contributing columnist to the Charleston Gazette.]

Labor, civil rights, protest, U.S. History, Civil Rights Movement, Legislation, human rights

[Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.]

Spread the word