Fast food strikes reached record numbers yesterday, with organizers estimating that some 1,000 stores and restaurants in 58 cities were affected by workers walking off the job.

In addition to growing in cities that have seen numerous strikes in the past, like New York City, Chicago and Detroit, the strikes entered into previously uncharted territory, including Raleigh, N.C., Wilmington, Del., Missoula, Mont. and dozens of other cities.

"I'm struggling,” said CVS worker Terrance Aranda, who was picketing outside his store in downtown Chicago Thursday morning. “I got two kids, go to school AND I work. I'm struggling. ... I got no food in my crib right now."

For Chicago strikers, many of whom have walked off the job three times this year, confronting management and informing them of the decision to strike is less nerve-wracking than it once was.

Strikers strode up to a manager at a downtown Walgreens and, without so much as blinking, delivered a letter explaining they were walking off the job; at a Bed, Bath and Beyond in the Loop, workers strode around the store encouraging coworkers to strike with them, seemingly unconcerned about what the watching manager thought.

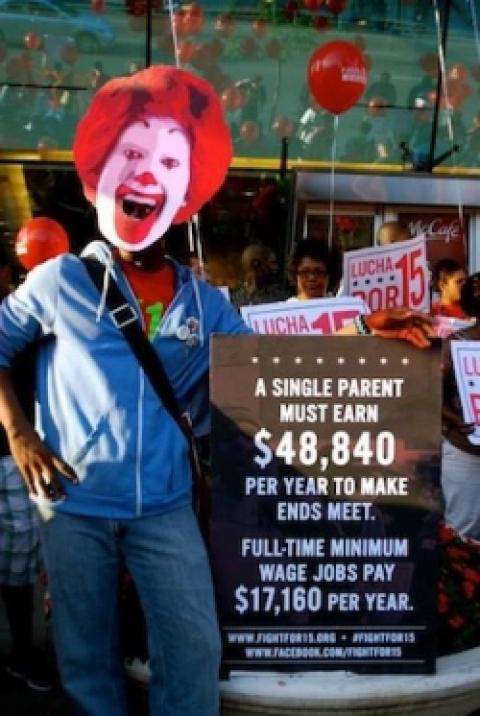

Striking McDonald’s workers were joined yesterday morning by U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), who marched into a downtown McDonald’s accompanied by strikers and the Hamburglar. Later, at a rally with workers and supporters, Schakowsky said, “When you win this fight, for $15 and a union, America will win, too.”

A sea change...

Since the first such strike in New York City last year, the expansion of low-wage jobs and the accompanying decline of well-paying union jobs have become a big topic in the media and on the street.

Major newspapers and stations are discussing the erosion of living-wage work, while the usual suspects like Neil Cavuto of Fox News and the opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal trot out business’s talking point that workers should glad to be employed. (Cavuto’s piece includes the line, “Did I ever tell you when I was a kid, you were grateful for any job you could find?”) Like Occupy Wall Street two years ago, these strikes have spotlighted the rampant inequality so characteristic of the 21st century American economy. And unions have become central to that conversation in a way that has not been seen in years.

The strikes also seem to have legitimated walking off the job as a tactic for workers, even those without a union (a possibility I discussed for Dissent earlier this year). On Monday, Green Fleet System port truckers also walked off the job for 24 hours in Los Angeles in an unfair labor practice strike. Unlike fast food workers, these truckers are seeking union recognition in the immediate future, and they struck in response to alleged union-busting by management. But the tactic does appear inspired by fast food strikers and could be used by other workers to take the offense in future union drives.

In addition, some fast food and retail workers have won tangible gains as a result of their strikes. Andrew Little has worked in the stock room at a Victoria’s Secret on Chicago’s Magnificent Mile for two years. After he struck earlier this year, he was immediately given a $2.26 raise by store management.

Little is sure the two are connected. “We won that through striking,” he says.

Similarly, according to striker and Chicago Whole Foods worker Trish Kahle, workers several Whole Foods stores received raises after striking, and management has backed off on the points-based attendance system long opposed by workers. And after workers at a Manhattan McDonald’s and a Chicago Dunkin’ Donuts spontaneously struck last month, they received air conditioning in their stores.

...or a PR campaign?

But as fast food and retail workers have continued to strike, some aspects of the campaign, which is backed by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), have been criticized. Writing for Vice after the last round of fast food strikes a month ago, Jarrod Shanahan accused the campaign of being more of a PR move than a true organizing drive:

The problem is, a successful union drive comes from the workers themselves. And there is a gigantic difference between a union drive and a public relations campaign, which is what FFF is corralling these brave workers into.

In a union drive, the bosses shouldn't find out that it's going on, or who is organizing it, until everyone in the shop has their back. That way if there is a move to fire them, everyone strikes. By contrast, Gregory Reyonoso, a spokesman for Fast Food Forward, was fired from his Brooklyn Domino's for being involved. A natural organizer, Reyonoso is now so famous that its very unlikely he'll be anywhere near a kitchen again any time soon. And this is where these union drives need to happen if they are to be successful, not in a press conference. It could be argued that it will only be through publicity that a union campaign ever succeeds in fast food, but the SEIU and NYCC is not telling workers that they're engaging in a PR exercise.

This dismissal doesn’t take into account the real gains workers have won as a result of striking. But it may partially reflect higher-ups' attitudes. In an interview with In These Times contributor Josh Eidelson for Salon earlier this month, SEIU assistant to the president Scott Courtney said, “The story is leverage in and of itself,” before quickly noting that worker action, too, is leverage. His initial statement could be seen as a tacit admission that the campaign’s perception of its power lies largely in its ability to drive a media narrative about low-wage work, rather than directly building worker power on the job.

SEIU President Mary Kay Henry also told Eidelson that in contrast to most union efforts, the goal of the campaign is “more about, ‘How do we shift things in the entire low-wage economy?’ ” It’s clear that, as with the SEIU’s Fight for a Fair Economy campaign around the time of Occupy Wall Street, the union sees a shift in the society-wide narrative around low-wage work as a central campaign goal—not, as with most union campaigns, organizing workers and developing their capacity to fight for a strong contract over the long-term.

Indeed, based on a report from an anonymous source who was present at an SEIU meeting with allies (and with confirmation from Courtney and Henry), Eidelson reported that internal discussion around the campaign’s endgame has focused on two scenarios:

First, escalating pressure on fast food corporations—McDonald’s, Burger King and Wendy’s, in particular—with the goal of reaching a joint agreement under which the corporations would cover the costs of improved labor standards in their stores. And second, a legislative push for local living wage laws requiring improved compensation for fast food workers. Because most cities lack the legal authority to mandate higher wages for jobs that aren’t publicly subsidized, that push would involve statewide ballot measures in 2014 to allow cities to hike private sector workers’ wages.

SEIU’s past deals with corporations in industries like healthcare, particularly prevalent under former president Andy Stern, have been criticized by some in the labor movement, such as In These Times contributor Steve Early and former SEIU staffer Jane McAlevey. In recent books, both critics have accused the union of being too cozy with corporations and too willing to negotiate deals favorable to companies out of a desire to grow union membership. In 2007, for example, leadership of SEIU Local 775NW in Seattle negotiated a secret deal with nursing home management over organizing certain nursing homes while leaving others nonunion. The Seattle Times reported that the deal included concessions to management, “As part of the 10-year agreement, SEIU Local 775 promises no strikes and agrees to let the nursing-home operators—not the union or workers—decide which homes are offered up for organizing. The union also agreed not to try organizing more than half of a particular company’s nonunion homes.”

In the case of fast food workers, however, such a deal with companies might be the most direct way to effect industry-wide change. Fast food restaurants are mostly owned by franchisees, whose ties to the parent corporations could be severed if workers take the step of voting in a union—leaving company deals or city-level legislation as perhaps workers’ best hopes.

Low-wage rage

At this point, however, as Henry and Courtney make clear, any talk of deals with fast food companies is pure speculation. And Ruth Milkman, professor of sociology and director of the Murphy Labor Institute at the City University of New York, says the strong media-focused element of the campaign should not discount the gains workers can make—nor the simple but crucial fact that low-wage workers are standing up.

“While there is certainly a PR element to this campaign, it is more than that,” Milkman says. “Unionization remains a distant goal, but there is the prospect of concrete improvement in the pay and conditions of the fast food workforce. And building momentum in the form of growing support from both fast food workers themselves and the wider public can only help with that effort.”

And as anyone who attends these strikes and speaks with a striker can attest, the Fight for 15 campaign has tapped into a seething anger among low-wage workers over their precarious position in American society.

“You come down from that office and work on the floor with me,” Andrew Little screamed through a bullhorn pointed directly into his workplace at Victoria’s Secret, directing his statement to management.

Referencing a nearby window display he said he set up reading “Life is Fabulous,” he yelled, “Life isn’t fabulous for me!”

Micah Uetricht is an In These Times contributing editor. He has written for Salon, The Nation, The American Prospect, Jacobin, and the Chicago Reader. Most importantly, he is also a proud former In These Times editorial intern. Follow him on Twitter @micahuetricht or contact him at micah.uetricht gmail.

Spread the word