Our Nation's Cities - Two Views - Can New York's de Blasio Stop Gentrification? Chicago's Rahm Emanuel - Mayor of the 1%

- Can Bill de Blasio Stop Gentrification? Can Anyone? - Michelle Goldberg (The Nation)

- Mayor 1% - Michael Hirsch (The Indypendent)

Can Bill de Blasio Stop Gentrification? Can Anyone?

Current market-based solutions only tinker around the edges.

By Michelle Goldberg

December 4, 2013

The Nation

(This article appeared in the December 23/30, 2013 edition of The Nation.)

On the campaign trail this year, Bill de?Blasio repeatedly channeled New Yorkers' anger over gentrification, the widespread sense that the city is turning into a playground for the rich that locks out everyone else. "I see people suffering and feeling like they're losing their grip on the place, and my job is to help New Yorkers live in New York. It's not to clear the place out and see it fully gentrified," the mayor-elect was quoted in New York magazine in June.

That means when de Blasio takes office, he'll be attempting to solve a problem that is plaguing major urban centers all over the world. Housing prices are soaring in San Francisco as technology workers stream into once-affordable neighborhoods like the Mission District. In June, London housing prices were up almost 10 percent from a year earlier, fueled partly by international speculation. Even the favelas of Rio de Janeiro are gentrifying. Reporting from one of the city's hillside shantytowns, The Guardian's Jonathan Watts wrote, "The most high-profile conflict here now is not between rival gangs, but between two European investors who are tussling over a prime plot."

So far, there isn't a city on earth that has developed an effective response to the gentrification juggernaut. New ideas, or rejiggered versions of old ones, are desperately needed because today's market-based solutions aren't succeeding. "All we're trying to do is tweak a system that isn't working, rather than envisioning something different," says Stacey Sutton, an assistant professor at Columbia who wrote her thesis on the gentrification of Brooklyn's Fort Greene.

The main tweak de Blasio has proposed is mandatory inclusionary zoning. Right now, inclusionary zoning is optional; developers are allowed to build additional square footage in exchange for making 20 percent of their units affordable. According to a report from City Councilman Brad Lander and the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, in most neighborhoods covered by the inclusionary zoning program, very few developers choose to participate. If they were required to, significantly more below-market-rate housing could be created. But probably not enough to change New York's housing dynamics. One of the neighborhoods where inclusionary zoning was most successful is Greenpoint/Williamsburg, where 949 units were created under the program (13 percent of new residential development). That, obviously, did not stop Williamsburg from becoming a symbol of gentrification.

"Zoning is a very weak tool," says Tom Angotti, a professor of urban affairs at CUNY. "Inclusionary zoning at best still relies on significant market-rate investment. It doesn't compensate for the rise or increase in rents and land prices."

A common progressive response to gentrification is to fight new market-rate development on the grounds that it drives up area prices. This is true on the micro-level; as luxury condos and stores arrive in a once-poor neighborhood, adjacent property becomes more valuable. But citywide, the law of supply and demand still holds. The moneyed arrivistes have to go somewhere, and if there isn't new housing available for them, they'll bid up the price on existing dwellings. Consider the housing crunch in San Francisco, perhaps the most development-averse city in the country, where rents are soaring by upward of 20 percent a year.

So what is to be done? Miguel Robles-Durán, director of the Urban Ecologies program at the New School, makes a convincing case that among the most useful tools are limited-equity cooperatives of the kind established under New York's 1955 Limited-Profit Housing Companies Act, better known as Mitchell-Lama. Under these programs, households own shares in a building, but the price at which they can sell their shares is limited for a certain period of time, usually twenty years. These arrangements offer stability of ownership without the skyrocketing prices that accompany real estate speculation. "The city needs to begin to experiment with alternative property systems," says Robles-Durán. "If you're not allowed to speculate on your property, developers will lose interest, and we'll finally concentrate on the property where we want to live."

It's tremendously unlikely, of course, that we'll see a substantial new wave of cooperatively owned housing anytime soon. In New York, the trend is in the other direction, as Mitchell-Lama buildings convert to having market-rate apartments. Part of what makes gentrification so thorny is the mismatch between the scale of the problem and the viability of potential solutions. If preventing widespread displacement means dismantling the real estate industry, we're in real trouble. Then again, the solutions that exist are implausible - but not impossible. A year ago, one might have said the same thing about Bill de Blasio becoming mayor.

[Michelle Goldberg is a senior contributing writer at The Nation. She is the author of The Means of Reproduction: Sex, Power and the Future of the World, and Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism.]

By Michael Hirsch

December 16, 2013

The Indypendent - Issue #192

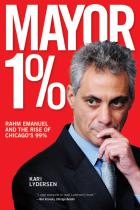

Mayor 1%: Rahm Emanuel and the Rise of Chicago's 99%

by Kari Lydersen

Haymarket Books

November, 2013

ISBN: 9781608462223

Price: $16.00

New Yorkers rejoicing in Michael Bloomberg's departure from office can be grateful for another small favor: they don't live in Chicago, where residents are stuck for at least two more years with an austerity-mad, street-brawling mayor who wields near absolute power over a City Council far more supine than the one we have here.

Bloomberg, the billionaire CEO, is rarely abusive in public. He speaks well of the city even as he helps friends pick its pocket. When defending neocolonial police action in communities of color, he doesn't gloat about it - at least not within earshot of the press. Chicago's sharp-elbowed Mayor Rahm Emanuel is more like the schoolyard bully who brazenly steals your lunch and gives it to the rich kids. Think of him as Bloomberg's nasty little brother. Same pedigree. Different tack.

Kari Lydersen's timely Mayor 1%: Rahm Emanuel and the Rise of Chicago's 99% exhaustively traces the rise of Emanuel, a one-time Clintonista, former congressman and Obama consigliore whose mayoral victory in 2011 changed politics in Chicago from a machine-dominated satrapy where city unions had some small influence to an autocracy where community services were drained, unions frozen out or broken and city workers bludgeoned.

Like Bloomberg, Emanuel drastically cut library hours. He privatized jobs - including cleaning services at O'Hare airport, which were then taken over by funders of Emanuel's election campaign. As with Bloomberg, he closed schools that needed help and even has his own anti-terrorism Keystone Kops unit, which played a key role in uprooting the local Occupy encampment.

Unlike Mike, he liquidated community-based mental health programs. These and other policies sparked a grassroots rebellion that has driven down his approval ratings to as low as 19 percent and clouded his 2015 re-election prospects. It has become clear to Emanuel's growing ranks of opponents that, as one protester told Lydersen, "It's not a question of whether the city is broke. It's a question of who the city thinks is valuable."

Chicago Politics

Despite its tradition of labor and community radicalism, Chicago politics has never been dominated by reformers. It's also been racially and ethnically abrasive, with the color line cutting through Chicago politics in ways that make New York's look like a Quaker meeting. There, as here, the finance, insurance and real estate sector (FIRE) calls the shots.

Lydersen's exposé of the mayor as an arrogant bully is perfect, and she succeeds brilliantly in setting the stage for the big question: if Rahm Emanuel (and by extension Bloomberg) do palpable harm, whose interests do they help? To a degree she makes the case. She shows Emanuel in his days as a top congressional Democrat playing footsie with the later-to-be-disgraced heads of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored mortgage giants that played a key role in fueling the housing price bubble that preceded the 2008 economic crash. She also covers his unwholesome relationship with a host of investment firms and his nefarious role as head of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in axing viable progressive candidates. It's a hefty indictment. I'd vote guilty.

What the book doesn't do is more tightly and instrumentally connect Emanuel to local and national corporate elites. With the Chicago area home to 25 of the Fortune 500 top corporations, just five are mentioned, and only United Airlines prominently. The other four are covered mostly in passing as incidental beneficiaries of the mayor's largesse. The agenda-setting City Club of Chicago and its grandees are mentioned once.

Still, it's one book, and it clears the ground for others. There's also no need to claim a one-to-one relationship between corporate needs and government policy. Often corporations disagree, or have conflicting interests, and the state has to play arbiter. It will be helpful if Lydersen's work stimulates others to explore the concrete relationships between city politics, public policy and business elites. If, as Marx argued, government functions as the executive committee of the ruling class, then how this executive body functions in practice needs exposing in great detail.

Sadly, no one has skewered Bloomberg with great investigative reportage as Jack Newfield and Wayne Barrett once did with Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani. Some 800 miles to our west, Lydersen points the way with a terrific muckraking tale of palpable harm to the people of Chicago by a smirking prince of the Democratic Party's neoliberal Wall Street wing. Lydersen's exposé is a slam dunk about who's not empowered, who's fighting back and why. It should provide a useful point of reference in judging the direction of the new de Blasio administration.

[Michael Hirsch, the first in his family to attend college, was a campus antiwar leader, a college professor in Boston as long as he could stand it, then a steelworker in Indiana until the mass layoffs of the early 1980s. Since 1985, he has worked as a labor editor and writer for three New York-based labor unions, as well as a contributor to numerous publications.]

Spread the word