Last month, when the college football players of Northwestern University tentatively won the right to unionize, the ruling by the regional National Labor Relations Board asserted that even though these young men were students at their school, they were also its employees. The decision—which could still be reversed—promised to make union men out of a group that looked quite different, at least on the surface, from the blue-collar factory workers who have traditionally been the face of American labor.

But to look around the modern landscape of American employment is to see a number of equally surprising organizing efforts. Music video dancers recently unionized. Adjunct professors on some college campuses have, too. In New York, jazz musicians have been pressuring nonunion nightclubs for pensions and other benefits, and on the Internet, video game designers have discussed the possibility of unionizing as a means of protecting themselves against game companies. Meanwhile, fast-food workers all over the country have been organizing with the help of the Service Employees International Union.

These people might seem like they have nothing particular in common. But behind their disparate organizing efforts, which come amid plummeting private-sector union membership overall, is a profound shift affecting nearly every industry in the American economy. More and more working people, at all levels of income, are operating in a gray area in terms of their employment status. For some, this means being hired as independent contractors or temps; for others, it means working for a subcontracting company or a franchise that takes orders from a massive corporation. For others still—this would include the college football players—it means being told that the work they’re doing is not work at all. As Boston University School of Management professor David Weil writes in his recent book, “The Fissured Workplace,” “employment is no longer the clear relationship between a well-defined employer and a worker.”

Most workers affected by this new paradigm are not at risk for being maimed or killed on the job, the way American miners were in the 1860s when dangerous working conditions spurred them to unionize. But they feel vulnerable in a different way. In a world where a full-time, long-term job with benefits at a single company is increasingly rare, these so-called precarious or contingent workers often lead unpredictable lives without financial stability or a clear set of similarly affected colleagues.

Under this new regime, formal unionization is out of the question for millions of Americans. In response, the labor movement has begun to experiment with new possibilities for how workers might negotiate for better conditions. Beyond outside shots at unionization like that of the college football players, worker groups and labor advocates are exploring ways to harness collective action without the official bargaining rights that made unions such powerful institutions in the past.

“Most of our labor law is built on this New Deal vision of the industrial workforce, when it was fairly clear who the employers were,” said Kate Griffith, an associate professor at Cornell University’s ILR School and cochair of the Precarious Workers Initiative. “Generally speaking, there wasn’t the same level of complexity that we have now.” Figuring out how to organize workers who would otherwise be excluded from the labor movement entirely, Griffith said, is an attempt to “adapt the old labor law model to new realities.”

As union membership in the country continues to decline—from its peak of around 35 percent of the private-sector workforce in the 1950s to 9.2 percent in 1994 to just 6.6 percent in 2013—the flowering of nontraditional organizing campaigns around the country can be seen as an indicator of how the job market has created new categories of Americans who see themselves as vulnerable to exploitation. Taken together, their efforts represent a major shift in thinking—both within the labor movement and outside it—about what today’s workers have in common, and what kinds of obstacles they face.

“There’s been a fundamental shift in the workplace in this country,” said Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Labor Center. “These are all experiments in trying to organize the new working class.”

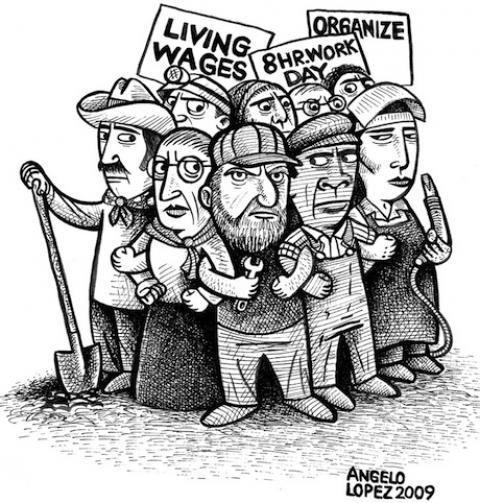

Labor unions first began to form in the United States during the mid-19th century, as the industrial revolution created a vast range of new jobs in which workers felt themselves to be at the mercy of their employers. Joining a union meant that individual dissatisfactions could be turned into a collective demand for better pay, less grueling schedules, and safer working conditions; by presenting a united front, workers gained leverage to pressure employers into signing contracts that guaranteed these and other protections.

Spread the word