Hillary Clinton's New Paleoliberalism; Sizing Up Clinton's Plans to Help the Middle Class - Here's the Rub: It Isn't Enough

- Hillary Clinton's New Paleoliberalism - Matthew Yglesias (Vox)

- Sizing Up Hillary Clinton's Plans to Help the Middle Class - Eduardo Porter (New York Times)

Hillary Clinton's New Paleoliberalism

By Matthew Yglesias

July 13, 2015

Vox

Hillary Clinton's record in office suggests that she is more liberal than either her husband or Barack Obama, and in a Monday speech outlining her economic vision she is set to confirm that.

Background briefing documents provided by her campaign to journalists in advance of the speech suggest she's making an effort to avoid a hard break with the previous two Democratic presidents, pointing out instead that times have changed since 1992 or since the circumstances of the 2008 economic crisis.

But the documents nonetheless hint at a fundamental philosophical difference: Clinton is less inclined to favor a market-oriented approach than a left-wing approach, a real change from the past quarter century of Democratic Party economic policymaking.

What we won't get on Monday is much policy detail to flesh out how this difference might look in practice. And many left-wing interest group leaders and intellectuals to whom this new way of thinking has been previewed have expressed skepticism to me about its sincerity. But history suggests that presidents generally try to implement the agenda they have promised, so it's worth paying attention.

The great divide in left-of-center economics

The biggest divide in American economic policy is, of course, the one that separates the Republican approach from the Democratic one. But within the left-of-center camp there is a long-running conceptual dispute between what you might call neoliberalism and paleoliberalism.

The keys to the neoliberal approach that dominated both the Clinton and Obama administrations are, roughly:

- The main way the government can impact the pre-tax distribution of income is by providing high-quality education to as many people as possible.

- Financial markets should be regulated to guard against catastrophe, but also should take a leading role in driving investment decisions across the private sector.

- To the extent that the education path fails to generate a satisfactory distribution of economic resources, progressive taxes should fund redistributive programs to produce a better outcome.

The paleoliberal approach denies most of this, harking back to an era in which government regulation and labor unions played a more direct role in compressing the pre-tax distribution of labor income and the financial sector was deliberately regulated in a heavy-handed way rather than allowed to lead the economy.

Neither Clinton nor Obama ever adhered purely to the neoliberal philosophy (both endorsed minimum wage hikes, for example, and saw a large constructive role for the government in guiding the health-care sector) but it has been a dominant strand in both administrations' thinking.

The new paleoliberalism

The philosophy Clinton will outline is essentially a modern-day revival of the old paleoliberal side of this fight. The ideas and people referenced on background clearly reflect the influence of a new set of institutions that have arisen in the 21st century that all aim to push against the hegemony of neoliberal ideas. Key focus points for this paleoliberal revival include the Washington Center on Equitable Growth that Clinton's campaign chair John Podesta founded in 2013 (and where, full disclosure, my wife used to work), the Roosevelt Institute, and George Soros's Institute for New Economic Thinking.

These groups promote concepts that we can expect to see Clinton embrace but that reverse the neoliberal formula of her husband's administration:

- The government should take an active role in writing economic rules that promote high wages, rather than relying on taxes and transfer payments.

- Financial markets do a poor job of guiding private sector investment (she will frame this as a critique of short-term thinking).

- Increasing educational attainment is an inadequate strategy for curbing inequality.

Clinton intends to bring this all together under the idea that high levels of inequality reduce the rate of economic growth rather than being an inevitable result of growth-friendly policies, technology, and globalization.

Conceptually, this sets Clinton up for a much more vigorous regulatory approach than either the Obama or (especially) Clinton administrations took. One that is much less worried that rules that reduce business profits will also reduce investment and growth, and one that is much friendlier to the idea that strong labor unions are not only compatible with but arguably necessary for rapid economic growth.

What does it mean?

Politics is more about concrete policy choices than abstract philosophy, and thus far we've seen relatively little indication of how Clinton would deliver on these ideas in a concrete way that differs from her predecessors.

Joining the congressional Democratic backlash against the Trans-Pacific Partnership would have been one way to do that, but it's a step she rather pointedly declined to take. Nor has she embraced liberals' call to expand Social Security, and she's been somewhat cagey about whether she endorses the movement for a $15-an-hour minimum wage. She certainly hasn't joined Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Martin O'Malley in calling for a breakup of Wall Street's biggest banks.

Many veterans of the intra-Democratic clash on economic policy doubt the sincerity of Clinton's moves to join their camp. Ironically, the fact that leading neoliberals like Larry Summers are now singing from a more paleoliberal songbook gives the old-time paleoliberals heartburn. They see a ploy by their old rivals to bend with the wind rather than breaking so as to retain control over the highest levels of the Democratic Party. Clinton's team is explicitly intending to stay abstract initially. Rather than a laundry list of policy initiatives, they want to paint a broad vision that they then fill out over time. Only when that happens will we really get a sense of how much Clinton intends to break with the past.

[Matthew Yglesias is Executive Editor of Vox.]

Sizing Up Hillary Clinton's Plans to Help the Middle Class

By Eduardo Porter

July 14, 2015

New York Times

Could President Hillary Clinton restore the American middle class?

On Monday, during her first major economic policy speech, Mrs. Clinton offered an informed diagnosis of the troubles afflicting "everyday Americans" struggling to get ahead.

Her prescriptions to help workers share more equitably in the fruits of economic growth are grounded in top-notch economic research. Yet for all the scholarship, the economic agenda outlined by Mrs. Clinton, the top Democratic contender for the presidency, still fails to measure up to the nature of the challenge.

"Previous generations of Americans built the greatest economy and strongest middle class the world has ever known on the promise of a basic bargain: If you work hard and do your part, you should be able to get ahead," Mrs. Clinton declared.

Continue reading the main story

The task, she continued, is to take that promise - eroded by corporate consolidation and technological change, and also battered by hundreds of millions of workers from China entering the global economy to compete with American labor - and "make it strong again."

Problem is, the role of the United States in the world economy looks nothing like it did for bygone generations. And the laws, norms and institutions that supported the middle were crushed in the four-decade-long effort ostensibly intended to help American business compete.

Today, the labor market has lost much of its power to deliver a living wage. More than 30 percent of men in their prime are either unemployed or earn less than what's needed to keep a family of four out of poverty, according to estimates by Lawrence Katz of Harvard. That's double the share of three decades ago.

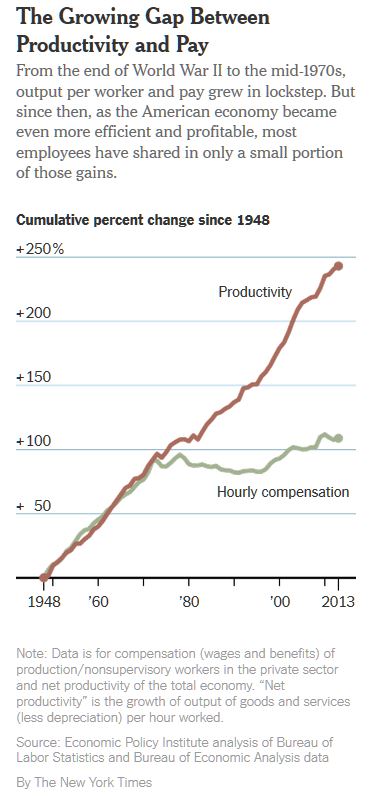

The Economic Policy Institute estimates that wages in the middle of the distribution have increased by all of 6 percent since 1979.

Stagnant wages have failed to keep up with continuing productivity gains, breaking a stable pattern that linked gains in output per worker and wages throughout much of the 20th century. And they are contributing to a vast, expanding income gap, the most extreme among advanced nations.

Workers in other rich countries are struggling with similar pressures. "We know that middle-skilled jobs were disappearing due to automation in the United States and Europe," said David Dorn of the University of Zurich. "Now we are seeing a similar pattern in Japan and South Korea."

Even Germany, an industrial powerhouse that has maintained robust employment during Europe's economic crisis, has experienced an explosion of low-wage service jobs. Last year, for the first time, it introduced a minimum wage, acknowledging that its once formidable trade unions could not protect workers at the bottom.

"There's a general perception that the global economy is moving in ways that disadvantage workers," said Paul Swaim, a senior labor economist at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the policy and research arm of the world's advanced industrial nations. "Even the Scandinavian countries have seen sharp increases in wage inequality."

This has set off a scramble for reforms around the world. In 2002, 12 countries in the O.E.C.D. offered in-work benefits - programs like the earned-income tax credit in the United States - aimed to lift the incomes of less-skilled workers without sapping their incentive to work. By 2010, the number had increased to 18.

Even Singapore, which imports millions of workers from the rest of Asia to perform low-skill jobs, has introduced a wage subsidy to help mostly older Singaporean workers whose wages have failed to keep up.

Mrs. Clinton's collection of proposals is mostly sensible. The older ones - raising the minimum wage, guaranteeing child care to encourage women into the labor force, paying for early childhood education - have a solid track record of research on their side. The newer propositions, like encouraging profit-sharing, also push in the right direction.

But here's the rub: This isn't enough.

It is critical to remember that, for all its riches, the United States lags behind the community of advanced nations in building a society that could cope with the harsh new global economy.

Not only does the American economy suffer from one of the least skilled work forces, according to the O.E.C.D. The American political system has not done enough to build a social insurance apparatus to help everyday workers and their families sustain prosperous lives.

The consequences of these shortcomings have been disastrous. They underscore the real nature of America's problem. It is not a lack of ideas about how to improve the lives of workers. It is the lack of political will to put them in practice.

Consider the Affordable Care Act, the biggest expansion of the nation's social safety net since the 1960s. At best, it matched what governments in the rest of the industrialized world have been offering their citizens for decades. But not a single Republican lawmaker supported the effort.

Judging by the visceral political warfare against universal health insurance, any strategy to lift the prospects of the American middle class looks bound to crash into an ideological wall.

Success won't hinge on a list of proposals. It will require reshaping entrenched political positions, and convincing solid majorities of voters of the vital role of government in their lives.

And it will require something that America hasn't experienced since President Bill Clinton was in office: a full-employment economy. With help from the Federal Reserve, the most important thing that Washington needs to do is keep the nation's job machine humming.

There is something a future President Clinton could do to encourage that accomplishment. In her speech, Mrs. Clinton noted how "many companies have prospered by improving wages and training their workers that then yield higher productivity, better service and larger profits."

She was speaking from the research of Zeynep Ton, from the M.I.T. Sloan School of Management. Jobs in the economy's largest, fastest growing occupations, in retail sales, food preparation and the like, are awful, she said, because "companies have created strategies that use people as interchangeable parts."

It doesn't have to be so. Professor Ton has identified companies, like the convenience store chain QuikTrip, that train and motivate their lowliest employees to improve service and hold down costs. These companies pay their workers more. Still, they record higher profits and labor productivity than their rivals, more sales per square foot and faster inventory turnover.

Why aren't most companies this way? Perhaps because labor costs are easy to measure, while the long-term benefits of investing in training a work force that can provide better service are not. Moreover, corporate executives focused on enhancing their own bonus through short-term measures have scant incentive to invest in developing talent.

A future Clinton administration might help change the norms of corporate governance to foster the kind of labor relations that everyday workers have not experienced in decades.

For this she would have an extremely powerful force on her side: demography.

"The labor force is already shrinking," said Alan Krueger, a Princeton economist who served as chief economic adviser to President Obama from late 2011 to the summer of 2013. "As it gets harder to hire, companies will come around to recognize that investments in their work force are in their long-term interest."

Relying on corporate incentives to change the economics of the middle class might appear irretrievably naïve. But it offers candidate Clinton perhaps her best shot. Otherwise she will have to build a strategy for all-out political war.

[Eduardo Porter writes the Economic Scene column for The New York Times. Formerly he was a member of The Times' editorial board, where he wrote about business, economics, and a mix of other matters.]

Spread the word