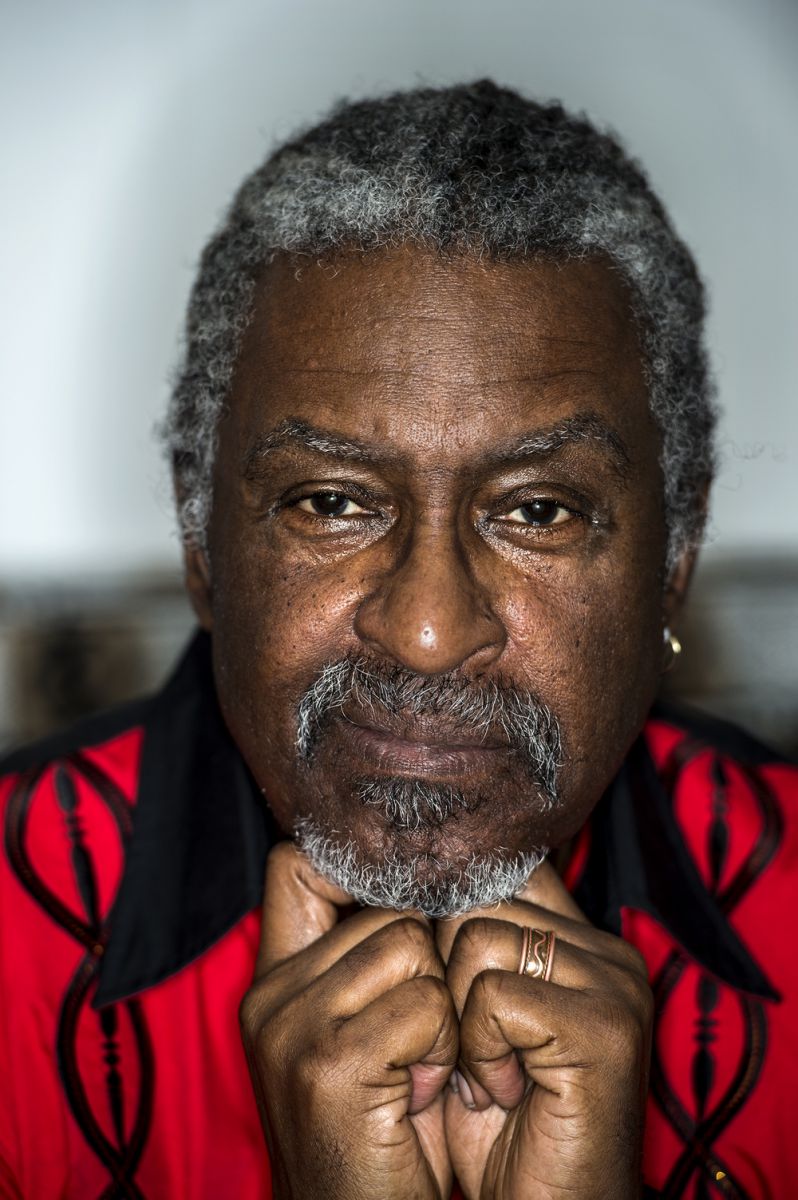

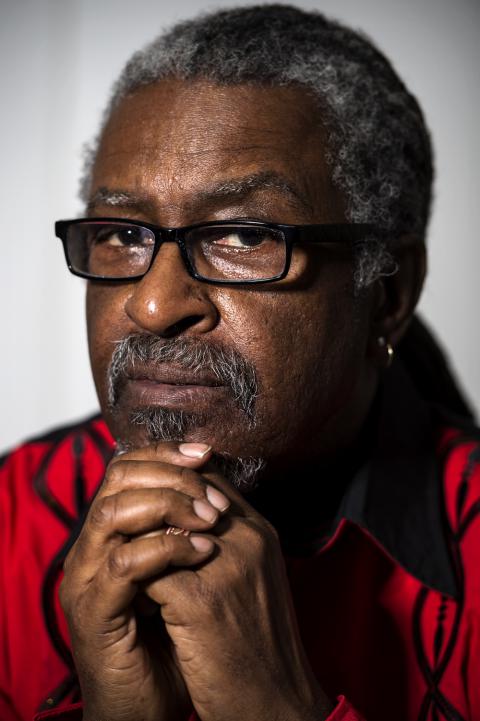

Jonathan Michels: You are a part of the New Great Migration of African Americans from the North who moved back down to the South following the Civil Rights Movement. Why did you decide to move to North Carolina?

Ajamu Dillahunt: We moved to North Carolina in 1978. By some people's standards, we still ain't from here, as they say. I don't know when you get to be from here, but we certainly feel like it.

We moved from New York. We decided to move south for both political and personal reasons. We wanted to be a little closer to our families. That was on the personal side. On the political side, North Carolina had that history of... the founding of SNCC, the sit-ins, Robert Williams in Monroe, and, in the more recent period, through the 1970s, the Wilmington Ten case. The resistance to that was important. And then the community work that we knew that was going on. We were like, "Yeah, this is probably a good place to be."

What were your perceptions of North Carolina and the South as a child growing up in New York?

I had visited in 1954, had come back to North Carolina with my grandmother. We went to New Bern, her home, and also Wilmington where we had cousins. We rode the bus. We get south of the Mason-Dixon line, and you've got to get in the back. Separate waiting rooms and all that stuff. I experienced that as a really young person. That's in your mind as well. Those years in between, I'm reading and watching, so the South is a dangerous place, it's a bad place. A place where we need to make some changes, a site of some important struggles.

There's the Emmett Till murder in Mississippi. Mississippi has always had this place in Black discourse as being the worst place you could ever be for Black folks. Medgar Evers is murdered there. There's Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner that are killed there. The list of atrocities just goes on and on.

I'm from that generation that was forever impacted by the murder of Emmett Till. He's murdered in 1955, right? He was 14 years old. I'm in the fifth grade. You're a young man in the 1950s and 1960s, and this is part of your understanding of what life is like in this country and what you might encounter.

On the real side, I understood that it wasn't quite as bad in 1978 as it was in 1958 or 1948-that there had been some changes and some resistance and people were standing up. North Carolina in particular had undergone some changes both on a political front and a legislative front. Some openings that were there.

We didn't move here with that kind of fear, [with the] preparation for the kind of repression that people faced in an earlier period. Of course, we weren't naive either. Glenn Miller, former Klansman... was out and on the prowl when we showed up. He was active prior to the Greensboro Massacre. The Nazi party was here and all that. Some of that was still there but not the level of repression that existed two decades or three decades before.

During the 1960s, as thousands of African Americans engaged in civil disobedience in demonstrations across the country, what role did you play in resisting Jim Crow?

AD: I was at school at Bradley in Peoria, Ill., and ended up becoming part of a demonstration that the local NAACP chapter had organized for, in retrospect a silly cause, but nevertheless they did it. This was in May 1964.

It was a barbershop, a White barbershop near the campus, and the owner refused to cut any Black person's hair. The campus was not in the Black community so local African Americans weren't looking to get a haircut there but some of the Black students were. Somehow, they made this an issue, and there was a sit-in that I just happened upon. I was coming from work. I was a dishwasher at a local restaurant, and I came from work and there they were, picketing in front of the barbershop and singing and chanting. I was in!

I don't think there was anybody recruiting for Freedom Summer at Bradley. I just didn't know about it. We just knew about sit-ins and this was a part of it. What led to the arrest was not being on the property, but we sat in the intersection and blocked it off. I got arrested for that.

I remember the Peoria police had police dogs, and the dogs were breathing down your neck. I was like, "Whoa." I hadn't expected that. But no beatings or anything like that. They picked people up and we spent just one night in jail. The charges were later dropped. But it was my first engagement in something important to do at that time. I felt more of a kinship and relationship to what was going on around the country with what other people were doing. The sacrifices they were making.

You received a Master's Degree in African Studies from the State University of New York at New Paltz, where you also worked for several years. Why did you decide not to stay in higher education?

AD: I was more interested in moving into some of manufacturing work and becoming involved in organizing at the workplace. That was a thrust that many in the movement at that time were looking at. Let's go to the workplace. Let's situate ourselves in manufacturing where we can organize. It's an important part of the economy, and we can really make some change in this society. We need to be at those critical areas where you can make things happen. Where you can stop bad things from happening and you can put pressure on the state, on the government in that way.

Worked at a plant as a machinist for awhile. A plant that was organized by the International Union of Electrical Workers at Wake Forest. I actually got laid off after one of the shutdowns. Not too long after that, the postal job came up and I went into the post office.

When you became a postal worker, did you automatically become a member of the union?

Not automatically. That's one of the issues about right to work. The idea of the open shop that even though an employer has a contract with the union that represents the workers there, because of the right to work laws, the employees are not obligated to join, although the union is obligated to represent them. The pay and benefits are the same. I joined. Of course I was going to join. I became active pretty quickly after I joined and did some things. Steward and research and education director and eventually... became president of the local.

The post office is a little different. The union is there for you to join, wherein the majority of the workplaces there is no union, so you starting from scratch. You've got to convince people why it's to their advantage to join. What's in it for them. Why should they take the risk of losing a job-or worse-in some cases. To convince them of that. Why is it important to build unity between Black and White workers? That's a common tactic that's used by the employers to split people along racial lines. For a number of historical reasons, Black workers are more prone to come forward and join faster because they know we need some kind of organization. We need something to protect us from these employers because we're catching hell and maybe it's the union that would do that. They feel it intuitively or they know something from history.. On the other hand, some White workers who are imbued with White supremacy and White privilege think, "That's a Black union. I don't want to be part of that." In fact, it's not a Black union. It's the Black workers who gravitated to it and maybe constitute the larger percentage of people who are active in it.

You helped create Black Workers for Justice in 1981. The organization emerged from an effort led by African-American women against racial and gender discrimination at a Kmart store in Rocky Mount, N.C.

AD: These women at a Kmart in Rocky Mount had been fired... by a White boss. They felt like it was discrimination in the stores. Most of the Black workers felt this but also this particular incident. These women came to Saladin and Naeema Muhammad who lived in the community and had been activists there. They organized some pickets, some motorcades through the neighborhood, targeting Kmart. Asked people around the state to the extent that they could do some leafleting at Kmart stores to try to bring pressure on them around the state.

They formed a workplace committee called Kmart Workers for Justice. People said we need to have an organization that does this. The manager eventually was fired. I'm thinking that maybe one or two of the people got their jobs back. They didn't win everything that they wanted. It was the action in Rocky Mount that got people to pay attention to workplace stuff. Three or four years before that, the sanitation workers in Rocky Mount had gone on strike. There's a kind of tradition of a struggle like that, but this was on another level. People got interested in that work. People came together. We had folks here in Raleigh and a couple of other places around North Carolina interested in joining and forming Black Workers for Justice.

What objectives did you hope Black Workers for Justice would achieve?

AD: The anti-worker climate, the anti-union climate here is legendary. It's epic. And all of the social forces that come together to make it such. Of course, the business community and in many cases, the religious community. The union busting that takes place and particularly now on a very sophisticated level with union-busting firms and attorneys and all that. Even before the advent of those more sophisticated specialists, turning to the church was always a tactic of the bosses. To win allies with the preacher who is going to convince the members to stay away from the union even if it got to the narrative of "If you join that thing, you're going to hell."

[The objective of Black Workers for Justice is] to give black workers a vehicle to participate in this broad, Black liberation struggle that is generally dominated by professionals, by lawyers and preachers. But understanding that, in the freedom movement historically, the troops have been working people. [That becomes] pretty clear during the Civil Rights Movement once you get below the layer of Dr. King and so-called "local leaders". But even a lot of local leaders in places all over the South were actually workers from factories and agricultural workers and farmers. We wanted to formalize that, to give people that voice and the chance to participate in that way. Also, to organize at their jobs to get power and protection on the job and to eventually to have a union to defend them. To deal with working conditions and pay and safety. Also, as a workplace community organization, [we wanted] not only to deal with the issues at the workplace, but also in the community that affects people's lives: education, police brutality, participation in the political process.

This past February, the Historic Thousands on Jones Street coalition held its ninth annual rally and march, which has grown immeasurably through the Moral Monday Movement. How did you become involved in these actions?

Black Workers for Justice? Immediately. We were on right away. At the time, I was working at the North Carolina Justice Center. They were part of the movement from the very beginning. One of the groups that came on board very early on. In both ways I was put into it. Happily.

[Rev. Dr. William J. Barber, II, president of the NC NAACP and leader of the Moral Mondays Movement,] supported the Electrical Workers Union [UE 150] in its struggle early on. I think they had a campaign at Cherry Hospital right there in Goldsboro. It's probably around 2004 or 2003. Just ahead of his election to the state leadership [of the NC NAACP]. Some of his members, particularly Larsene , members of his church, Greenleaf [Christian Church], got him involved, and he spoke and supported the union and talked about how important labor was.

I tell people that I didn't join the NAACP until I was in my sixties. Prior to that I just didn't think it was the kind of organization that was effective and really fought in the way that I thought it should and could with some exceptions. The local leadership in North Carolina had been pretty ineffective, we thought. Compromised. Not militant and outspoken and energetic in a way that we thought it needed to be. Here, Reverend Barber brings all of that to his leadership.

It was clear there was going to be some kind of shift. Now, we couldn't predict that it was going to be of the nature that it has turned out to be. Moral Monday. Forward Together. Could not think of that at all. That was even prior to the development of HKonJ. That coalition. That comes the second year into his presidency. You can't paint on that, but you could see from the issues that he was tackling, the kind of vision that he was laying out that it would be some kind of change in the state.

What has the Moral Monday Movement come to signify for you?

We're in a period where we're really appreciating all of the work and the struggles that we've been involved in and that we've witnessed during that time, in some ways, coming to fruition. To see people out in this level. It's just about unprecedented. Certainly since we've been here. I don't know if there are any other points in history where we've seen these kinds of mobilizations. Some of the historians know some minor pieces, but in terms of movements, this is it.

On the last Moral Monday [on July 29, 2013]... we were at the rally and of course Reverend Barber was speaking. Maybe it was before he spoke when they were singing-the Forward Together Singers. Standing slightly behind, Reverend Mendez and Reverend Johnson and they're like really into it. You could see they were captured by what was going on on the stage. Here are two activists who I've known for a long time, actually before I came here in 1978. The kind of struggles that they've been through, the kind of work they've put in in Winston and Greensboro, and the Darryl Hunt case and Kwame Cannon, and the Kmart workers being organized, the Greensboro Massacre, all of these kinds of things. Here they are still in it. Still participating. But also really feeling this moment. It was pretty emotional.

Those are little things, but it's people coming out. You spend years and years of small actions and pickets and demonstrations, and maybe you win a concession here with this employer or the city concedes to do something that you demanded. But to see people come out at this level with this consistency and with this spirit and even anger. There's Moral Monday and there's the folks that come out and there's the HKonJ coalition, but if you go in a little deeper, there's these other movements that are part of it. Other activities. Other struggles that are either identifying with Moral Monday and the Forward Together movement or the movement has looked at their struggles and embraced them.

The year before we got a campaign to defeat Amendment One, the marriage amendment. The progressive forces lost, but it was a hell of a fight that was waged. I think a lot of people's opinions about it was turned around, particularly in the African-American community. All of these clergy came out and said this is about fairness. There were gains made in that. In the midst of the Moral Monday stuff, you get teachers with the 2020 movement really pushing the NCAE [North Carolina Association of Educators] forward. They're fighting and battling. They're taking stuff to all their school boards and county commissioners to resist the 25 percent rule that the General Assembly passed. They're organizing and running and winning.

Then [there is] the Raise Up movement. The environmental justice movement. The fight against the coal ash dumping. That's part of the resistance against Duke and the energy companies. It's a wonderful time to do a critique of the system at this point. To continue the conversation of the one percent that the Occupy Movement brought forward.

Wow. What a wonderful time to be able to talk about the relationship between the economic structure and the destruction of the environment and who's holding back on the necessary changes. This is a good time. They call it a perfect storm of events. You couldn't have planned it this way. Things have just developed, and you've got the issues and the right people in place to push it forward. It's just a good time. Hopefully we'll come out with some victories and some power.

Robert Williams was the president of the North Carolina NAACP and an ardent proponent of Black self-defense.

Medgar Evers was the president of the Mississippi NAACP, killed in his own driveway by a white supremacist on June 12, 1963. Andrew Goodman, James Chancey, and Michael Schwerner were killed by members of the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan after they began working to register Blacks to vote the summer of 1964.

On November 3, 1979, five people were killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party during a protest against white supremacist violence.

A 2013 law passed by the North Carolina General Assembly eliminated public school teacher tenure and was replaced by a rule in which 25 percent of teachers could receive four year contracts instead of new, year-to-year contracts. [http://www.wral.com/senate-panel-oks-eliminating-teacher-tenure/1232521…

Spread the word