books Was Reconstruction a Success or a Failure? And Why It Matters - A Review and Commentary on This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed

Part 1: The Civil Rights Movement and Guns

Charles E. Cobb, Jr. has told an amazing story about how armed self-defense helped make the civil rights movement of the 1960s successful. His book, This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed, wrestles with the tension between the non-violent approach of the civil rights movement, including the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the need for armed self-defense in the black communities of the south. For Cobb, non-violence was just a tactic made necessary by the ugly realities of the segregated south. It was not a Gandhian crusade. SNCC's acceptance of armed self-defense inside black communities they were trying to organize helped keep the organizers alive.

As I read his story of the armed black communities, a question rose up in my mind. Why didn't the ending of Reconstruction in 1877 result in the disarming of the black population? How could all those guns (and the right to bear them) have stayed in place in a population that was being systematically suppressed? Guns did not get confiscated. Pretty remarkable. Almost a miracle.

This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible

By Charles E. Cobb, Jr.

Basic Books, 320 pages

Hardcover: $27.99

June 3, 2014

ISBN 13: 978-0-465-03310-2 ISBN 10: 0465033105

Take for instance Cobb's story of Mr. Joe, a black Mississippi sharecropper in his 70's who gave shelter to Cobb and other civil rights workers in the 1960s. One morning shortly after Cobb arrived, the local sheriff raided Mr. Joe's farm. During the illegal search of the house, the sheriff confiscated Mr. Joe's shot gun. After the sheriff left, the organizers told Mr. Joe, who was illiterate, that he had a right to his gun because it was guaranteed him in the constitution, which was in this book they held up to show him. A little while later, the organizers found that Mr. Joe and the book were gone. Joe had gone to the sheriff's office to demand the return of his shot gun. He walked alone into the sheriff's office and told him he had come to get his gun back. The sheriff said no, he couldn't have it. Joe held up the book and said he had a right to that gun because it said so in this book. And the sheriff gave him back his shotgun.

Just when everyone back at the farm was beginning to worry about having encouraged Mr. Joe with stories about a book with laws in it, and was about to go searching for him, he returned to his farm with his shotgun in hand, his arms raised over his head in triumph. Everyone was relieved and amazed. How could this happen? What does it mean? It doesn't fit the image of the armed segregationists looming over the meek nonviolent crusaders. It was a small moment of triumph that must have caused both amazement and given everyone who witnessed it some glimpse of the power which the movement had at its disposal.

Not only did the black community hold on to their guns during even the darkest years of racial segregation and violence, but white southerners seemed to be operating under the assumption that the right to bear arms transcended segregation. How did this happen? The answers lie in the period we know as Reconstruction, 1865 to 1877.

Cobb says "Reconstruction did not fail; it was destroyed." He reviews the history of that period (1860-1877) recounting the role of blacks in the Civil War and Reconstruction and the violent rise of segregation and lynchings all over the south after 1877. "Redemption", as our history books call the brutal ending of Reconstruction, gave rise to the New South and its separate but equal fiction that lasted all the way until it was rejected by the famous1954 Supreme Court decision "Brown vs. the Board of Education." Somehow, through all of these years, blacks kept their guns. While guns were part of rural life and used for hunting and subsistence, the widespread ownership of guns in the black communities still seems like an anomaly. It certainly does not fit the history of the south we have been spoon fed since "Birth of a Nation" hit the silver screen back in 1915.

When we look at the history of segregation today, it seems obvious that Reconstruction failed. After all, how else could white supremacy have achieved the predominance we all witnessed? But do we ask ourselves if the civil rights movement failed because racism did not end and de facto segregation has grown all over the country, north and south, since then? No, there is no doubt that the civil rights movement triumphed. Segregation was outlawed. Martin Luther King, Jr is the name of a national holiday. Streets are named after him. Today we even have a black President. No, we all know that the civil rights movement did not fail, even after Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered. It achieved a limited but very significant goal.

If we take this same understanding of what success means, i.e. the achievement of limited but significant goals, and apply it to Reconstruction, we may find that Reconstruction did not fail after all and that it too triumphed. If black armed self-defense made all the difference in the eventual triumph of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, as Cobb shows in his book, perhaps it is not unreasonable to look more deeply into role armed blacks played in the history of the 19th century and the outcome of the Civil War. Our history books do not tell this story either.

One history book, Black Reconstruction in America: Toward a History of the Part Which Black folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 by W.E.B. DuBois written in the 1930s, does tell the story. DuBois tells a story of class conflict and revolution that under laid the Civil War. Because DuBois associated himself with the U.S. Communist Party, he has been ignored in our schools, pilloried and rejected as historians defend the myths of official history. While Cobb brings the real story of armed self-defense in the 1960s into the light, he stops short in his analysis of how those guns impacted the history of Reconstruction.

What Du Bois shows in Black Reconstruction is that the Civil War would not have been won by the Union without black soldiers and that slavery would not have ended without the empowerment of black ex-slaves during Reconstruction when they were used to rip apart the social fabric that the slave owning class had created. This is a shocking notion that contradicts what most of us have been taught about that period. But it is a powerful notion that throws a whole new light on reconstruction, just as Cobb did in pointing out how guns made all the difference during the civil rights era of the 1960s.

In his first chapter where he reviews the history of the Civil War and Reconstruction, Cobb rightly points out that the guns which came back from the civil war battlefields with black Union soldiers played a major role in Reconstruction. Later in the book he also credits black soldiers returning from World War II to a segregated south for their leadership role in the fight for voting rights in the 1960s. From DuBois class conscious perspective, the difference is that during the Civil War, armed black soldiers and veterans played even a larger role than we give them credit for. They went beyond self-defense to armed insurrection against slavery, to the overthrow of the slave-owning class.

Part 2: Our Civil War Was a Revolution

W.E.B. DuBois, who was born in 1868 shortly after the end of the Civil War, viewed the civil war as a revolution. Today, in the United States, the only "revolution" we study is the American Revolution of 1776 which was in fact a war of independence. It substituted an American ruling class for the British ruling class. DuBois considered the destruction of slavery as a revolutionary change and its primary actors were the black slaves themselves. This key insight illuminates the historical roots of the role of armed self defense by the black community in the 1960s so well described in Charles E. Cobb, Jr.'s This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed.

Destroying a class system is what revolutions do, not just substituting one group of rulers with another. In Russia in 1917, the Russian Revolution liquidated the Tsar and the land-owning aristocracy and armed and freed the peasantry. No one would seriously dispute that it was a revolution. In the United States in the 1860s, the Civil War liquidated the slave owning class and abolished slavery, arming and freeing the slaves. Beyond self-defense, the insurrectionist, revolutionary role of guns in the hands of black slaves was key to the success of our only real revolution and the Union's victory. And for that very reason, it is ignored and lied about to this day. Just as slave rebellions are ignored and vilified, along with John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry that is dismissed as the act of a mad man. If you think that way, you cannot possibly give credit to the incredible, heroic role of armed blacks in destroying slavery and reconstructing a free south from the ashes of the Civil War.

The Emancipation Proclamation came about in 1863 because the war was going badly for the north. Slaves were being forced to support the Confederacy's war efforts, to supply food, and support Confederate troops. The Emancipation Proclamation was a war time measure directed against the enemy. Many politicians at the time saw it as a temporary measure that should be rescinded when the war ended. Except for the fact that slavery itself was at the heart of the Civil War.

Once the abolition of slavery was in place in 1863, the logic of freedom propelled blacks into the struggle, undercutting the confederacy on many fronts and supplying much needed extra forces for the Union army. DuBois called this "The General Strike." Cobb points out that one-fifth of the black population went into the Union army. Lincoln and the generals knew they needed black troops to win and they forced a reluctant congress to go along.

Black soldiers in the Union army were committed to fight the Confederacy to the death, with none of the doubts that might have plagued white soldiers and politicians. Even if the country did not understand that slavery had to end if the war was to be won, those fighting the war did. At the end of the war, when victory was in sight, the United States ordered General William Tecumseh Sherman to march to the sea, doing as much physical damage to slave-owning classes and their property as he could, burning plantations and freeing slaves as he cut a wide swath across the heart of Dixie from the Mississippi river to the coast of Georgia. Tens of thousands of black slaves marched to the sea in his wake. Their numbers grew as the flames rose. Sherman's march to the sea was the Hiroshima of the Civil War.

In spite of Sherman and the Union victory, however, slave owners attempted to reestablish their power during the "first Reconstruction" through such measures as the Black Codes passed in 1865 and 1866 in most southern states. The resurgent slave owners were attempting to re-enslave blacks and restore their power base. The specter of a renewed Confederacy forced the north to take steps to complete the revolutionary destruction of slavery in order to consolidate their hard-won victory on the battlefield.

Radical Reconstruction was as much a war measure as the Emancipation Proclamation. Northern troops occupied recalcitrant southern states, and along with armed blacks, kept slavery from coming back. Black freedmen were the only group in the south that could carry the destruction of the slave owning class through to completion on the ground. Blacks and allied whites (scallywags and carpetbaggers we have called them) in the legislatures ratified laws to make it happen. Congress and the nation were forced to pass the 14th Amendment to the constitution guaranteeing equal protection under the law to all citizens. Southern states had to ratify it if they wanted to regain representation in the US Congress. Union soldiers in the south during Reconstruction made sure the process was not suppressed.

Armed force alone was not enough, though, to end slavery. Northern capital and capitalists moved south to set up a nonslave economic system, buying land and setting up businesses, banks, mercantile networks, etc. that would pose no threat to the newly united nation. Ex-slave owners and their allies bought into the "New South" and its carpetbagger money when they saw it was their only real choice. Defeated slave owners either moved out of the south (to California's central valley, for instance) or became capitalists employing free labor. They may not have liked it, but they did it.

Conversion to nonslave capitalism was accomplished by 1877 through economic transformation on the ground enabled by state governments relying on blacks voting at the polls and in legislatures, and holding guns in their hands. Then, satisfied that the New South would play along, the Congress withdrew support for black civil rights and let racist southern locals have their brutal way, including racial segregation and disenfranchisement (but not slavery).

The shining rhetoric about freedom and equality coming out of the halls of power in the 1860s and 1870s was as much of a smoke screen then as it is now with our transparent wars in the oil-rich middle east. Such rhetoric during Reconstruction covered the real motives of the economic power brokers in their drive for completing the victory of the Civil War. Abandoning the freed slaves to the merciless hands of the New South, once their usefulness was over, demonstrated the real nature of our economic system of government and power. Redemption, sharecropping and segregation was acceptable as long as it did not restore slavery. Slavery ended at the point of a gun and armed black ex-slaves made it real. And that was a revolution no matter how you look at it.

I celebrate Radical Reconstruction, a brief moment of glory, no matter how blindly and halfheartedly we, as a nation, did it. I celebrate my great grandfather's (Robert Richards) service in the Civil War with the Wisconsin Volunteers and his combat in Mississippi where he was wounded. Did Reconstruction end racism? No. Does that make it a failure? No again. Considering it a failure is like considering the civil rights movement a failure because it only abolished segregation and not racism. In history, the possibilities of any epoch are what people understand and grasp. These possibilities are shaped by history. As Cobb so ably describes, armed black sharecroppers understood what was possible in the 1960s and took steps from there. Armed black union soldiers understood it in the 1860s in the same way. Abolition of slavery was a possibility then and they made it happen.

From this standpoint, Mr. Joe's triumphant reclaiming of his shot gun from the hands of the sheriff casts a direct light on the fact that during the Civil War and Reconstruction, armed black citizens had earned their right to bear arms. The lessons of history do not have to be taught in school to be real.

"Redemption" and racial segregation that followed the overthrow of Reconstruction was a racist nation's gift to its defeated white southern brethren. White unity in an orgy of racism helped relaunch the U.S. drive to world dominance that had been briefly derailed by the civil war. International affairs played a role in the modern era too, when the continuation of segregation in the anti-communist post-World War II era openly contradicted the United States' pretensions about spreading democracy against the evils of communism and made it imperative to end it. These kinds of considerations may get votes in the legislatures, but they do not play in the local power structures motivated by much more immediate concerns. There, white supremacy got its way but knew its limits. And if anyone forgot the limits, black rifles were there to remind them. Our history cannot be reduced to propaganda for the current occupants of powerful offices. It goes deeper and beyond politics.

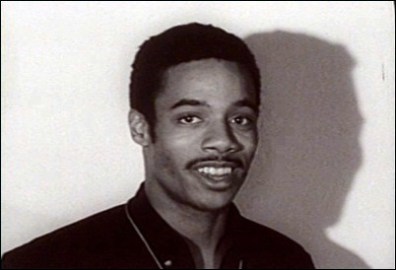

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., 1963. Author of This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed.

Photo from "We'll Never Turn Back" by Harvey Richards

Charles E. Cobb, Jr. has made great contributions to our history, first as a field secretary for SNCC in the 1960's and now as an historian and author of This Nonviolent Stuff'll Get You Killed, helping us to open our eyes to the realities that ended segregation. These realities, including armed self defense by the black community, go all the way back to the civil war. To understand what happened, we have to add the notions of class struggle and revolution back into our world views and vocabularies. Because that is the only way to make it comprehensible and the only thing that can give us the tools we need to make a better future.

Spread the word