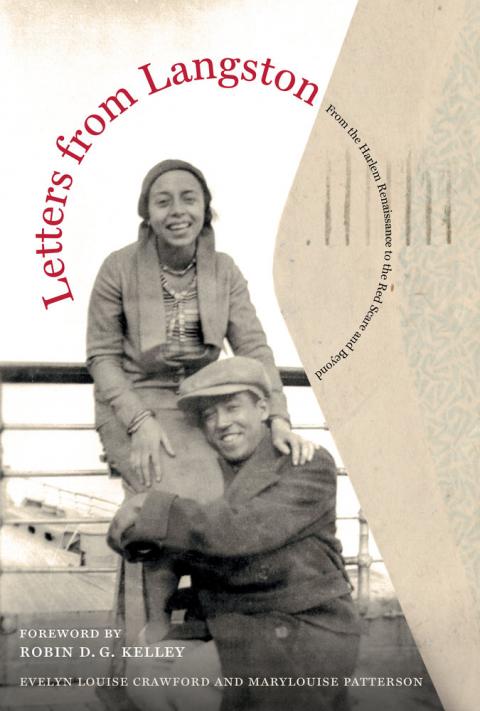

books Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond

Edited by Evelyn Louise Crawford and MaryLouise Patterson

Forward by Robin D. G. Kelley

University of California Press, 437 Pages

Paperback $27.95

February 2016

ISBN: 9780520285347

Evelyn Louise Crawford, a retired arts administrator and consultant, and MaryLouise Patterson, a pediatrician, have assembled correspondence of their parents - Matt N. Crawford, Evelyn "Nebby" Graves Crawford, and William "Pat" L. Patterson and Louise Thompson Patterson - with Langston Hughes, one of the pre-eminent poets of the 20th century. With the exception of William Patterson, whose birth was in 1891, the other parents and Hughes were born around the turn of the last century, less than two generations after the nation's Civil War and less than two decades after the defeat of Reconstruction.

An attorney by trade, Pat, as he was called by friends, established a thriving law practice in Harlem during the 1920s. He was drawn into left-wing politics after coming to the defense of Italian workers and anarchists Nicola Sacco, a fish peddler, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a shoemaker, who after being falsely convicted, were awaiting execution in Boston. Pat saw in the Sacco and Vanzetti prosecution an example of the "justice routinely denied Black Americans," the editors note. Pat's subsequent work led him to the Communist Party, USA, and a career as one of the century's great civil rights champions. His work is well documented in his autobiography, "The Man Who Cried Genocide," and Gerald Horne's "Black Revolutionary: William Patterson & the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle."

Louise Thompson Patterson, though not as well know as Pat, was an extraordinary organizer, and an outstanding writer and speaker. She was among the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance and Hughes's close friend and confidant.

Matt N. Crawford eschewed the comfortable middle-class life of a medical doctor to participate in and lead countless civil rights, peace and democratic struggles from the 1930s through the 1980s. In 1932, he was among a group of young African Americans organized by Louise who traveled to the Soviet Union to make a film about race relations in the U.S. Among the many hats Matt wore was that of a labor activist. He took part in the famous 1934 San Francisco general strike, and later was a founder of the National Negro Labor Council.

Evelyn Graves Crawford, a childhood friend of Louise, was the only one of the four parents who never joined the CPUSA, but she, too, was ensnared in the anti-communist dragnet for her work and associations. In 1953, she lost her position as an administrator at the U.S. Civil Service Commission in San Francisco and also most of her retirement benefits. Throughout she was a bulwark, her home a refuge for Hughes on the West Coast. Her generosity of spirit shines through her letters. It was with her and Matt that Louise and Pat would have left MaryLouise had they both been imprisoned during the witch-hunts. Pat did serve time, but Louise managed to avoid imprisonment.

The correspondence begins in 1930 with a letter from Louise to Hughes about her dismissal by her white patron, Charlotte Mason, who had hired Louise a year earlier as a secretary for Hughes and writer Zora Neale Hurston. Mason, who Hughes and Hurston referred to as Godmother, also cut off Hughes. Hughes's letters to Louise reveal his despondence over his loss of Mason's patronage as well as his dispute with Hurston about the authorship of the play, "Mule Bone." Hurston not only broke with Hughes over the play, but also disavowed his co-authorship of the work.

Hughes by this time had made a name for himself as a poet, but he was far from economically secure. The person we have come to hail as our brilliant poet laureate, novelist playwright, librettist, columnist, we meet in the pages of "Letters" as a struggling young author barely able to make ends meet. But throughout his time of need, Louise was there to lend him a hand and a few dollars when she had it.

Louise, whose middle name was curiously Alone, and Hughes shared similar childhoods. Both were separated from their fathers. And while their mothers struggled to earn a living, Louise and Langston passed much of the time with relatives or alone. They both moved frequently and, therefore, rarely enjoyed the stability of home or school.

By the late 1920s, Louise was immersed in Harlem's cultural and political life, and like many others at the time, gravitated to the Left. Her letters celebrated her growing radicalism as well as the confidence and hope it provided her. In a January 1931 letter to Nebby, she wrote: "Don't you love those things Langston is doing? I have hopes, high hopes, that he will become our real revolutionary artist." By 1932, Louise's organizing prowess brought her to the attention of James Ford, the CPUSA's most prominent African American leader at the time. Ford asked Louise to assemble and lead a delegation of African Americans to help produce a film in Moscow about "Negro" life in the United States.

Before recruiting the cast for the film, Louise brought together an interracial organizing committee, which was tasked with raising funds for the travel expenses of the film's participants. The group of 22 young African Americans sailed for Moscow in June of 1932, but the film for various reasons was never completed. Although the project faltered, time spent in the USSR profoundly affected the travelers. Louise later joined the CPUSA, as did Matt. The trip inspired two of Hughes's most revolutionary and controversial poems, "Good Morning Revolution," and "Goodbye Christ," two works, which he was later pressured to disavow.

A letter from Matt to Nebby during his Soviet trip reminds us of the pull the Soviet Union held for those on the Left and anyone seeking an alternative social, economic and political order. African American visitors were especially impressed by the strides that the people of the Asian republics were making under socialism. Matt pondered what socialism could hold for African Americans: ". added to the actual struggle to live is the necessity to readjust myself to a Negro's position in `White America.' I have thought of the added pleasure of our lives together if it were possible for us to live under a system such as Russia is building."

That hope and a willingness to struggle for a world of justice and equality pulses through the correspondence, not only in the 1930s and 1940s, but in the dark days of the 1950s as well. The letters also reveal the breadth of the Left community in the 1930s and 1940s. The parents corresponded and worked with a who's who of the Black freedom struggle and cultural movement, including icons such as W.E.B. Dubois and Paul Robeson.

The humor I associate with Hughes through much of his work, but especially initially discovered through his Jesse B. Semple columns is on display in "Letters," and not from Hughes alone. One example is a 1957 letter from Pat to Hughes after he, Louise and MaryLouise attended Hughes's play, "Simply Heavenly." Not pleased with what he saw, Pat wrote: "The characters ate, danced, prepared for gratification of sexual desires as though these things constituted their range of thought and action." Hughes in response thanked Pat for his critique.

A letter by Nebby is one of my favorites in the collection. In a postcard to Hughes in August 1958 during a family vacation in Mexico, she captured my feelings: "We finally got here and are having a fine time. Such a beautiful land and so many beautiful people. We saw our first bull fight today. My last."

Readers will more than likely draw parallels between the movements and campaigns discussed in the letters and those leading up to the present. For example, the Scottsboro frame-up of the 1930s and the work of the International Labor Defense recall today's fight against mass incarceration. The Sojourners for Truth, an organization of African America women organized during the 1950s witch-hunts, foreshadowed the international campaign to free Angela Davis. Charging the U.S. government with genocide as Pat did at the United Nations leads us to Black Lives Matter and the call for reparation. The National Negro Labor Council laid the ground for the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

The letters reveal that Hughes was targeted during the McCarthy period and performed what some might call a tactical retreat. Unlike others, he never named names. We see, though, that his ideals remained intact. And we witnessed the importance of not only a progressive movement to help point the way and steady your gait but the embrace of friends and loved ones to keep your from falling.

Long after Hughes's death, the editors note, their parents remained active. Pat stayed in the CPUSA and was an advisor to leaders of the Black Panther Party. Louise continued political and cultural work, including in Harlem. Matt was an elder statesman in various political movements in the Bay Area.

To prevent the reader from getting lost among the names, organizations and acronyms, the editors provide detailed notes, footnotes, commentary, a glossary and an index. I wish the editors could have provided more from the McCarthyite 1950s. In their notes they remind us that during that period, it was common knowledge that your letters were read, your phone tapped and your travels monitored. I finished the work with a deep respect for all the parents. I am fascinated with what Louise Patterson was able to achieve and I believe her life story cries out to be told.

Robin Kelley's wonderful foreword deftly places the letters in context and draws lessons for today. He wrote: "The beauty of "Letters from Langston is that it provides a rich and fascinating alternative history of the American Left through Black eyes."

I think the Pattersons and the Crawfords would be proud of their daughters for patiently and lovingly assembling their letters to Langston and inviting us to share these heroes victories and defeats, and the important lessons their lives and work provide.

[JJ Johnson is a retired labor journalist.]

Spread the word