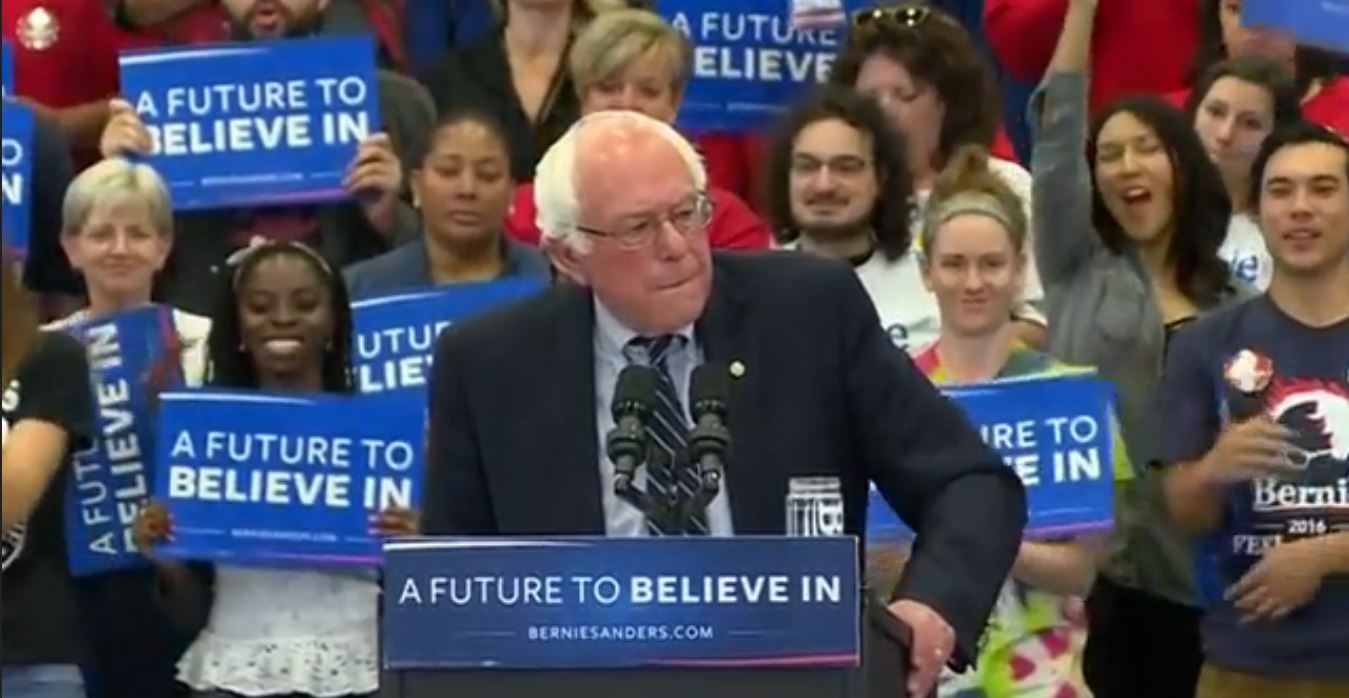

After Bernie Sanders's defeat in New York last week, his chances of winning the Democratic nomination are dwindling. Yet, even if he loses this campaign, a poll published Monday suggests that Sanders might have already won a contest that will prove crucially important in America's political future.

The poll of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 finds that Sanders is by far the most popular presidential candidate among the youngest voters. This group's attitudes on a range of issues have become more liberal in the past year.

The data, collected by researchers at Harvard University, suggest that not only has Sanders's campaign made for an unexpectedly competitive Democratic primary, he has also changed the way millennials think about politics, said polling director John Della Volpe.

"He's not moving a party to the left. He's moving a generation to the left," Della Volpe said of the senator from Vermont. "Whether or not he's winning or losing, it's really that he's impacting the way in which a generation — the largest generation in the history of America — thinks about politics."

Apparently, Sanders's popularity with young voters isn't just some shallow fad or a cult of personality with little connection to substantive questions of politics. Young people, it seems, are taking Sanders's ideas to heart.

April 25, 2016 7:24 PM EDT - Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders takes on "millionaires and billionaires" as he makes his final pitch to voters in Pittsburgh before Tuesday's Pennsylvania primary. (Reuters)

In one of Harvard's polls of young people in 2014, the number who agreed that "basic health insurance is a right for all people" was 42 percent. That figure increased to 45 percent last year and to 48 percent in Monday's poll.

The share who agreed that "basic necessities, such as food and shelter, are a right that government should provide to those unable to afford them" increased from 43 percent last year to 47 percent now. The share who agreed that "The government should spend more to reduce poverty" increased from 40 percent to 45 percent.

It's rare, Della Volpe said, for young people's attitudes to change much from year to year in Harvard's polling, and even more remarkable for so many of these measures to shift in the same direction at the same time.

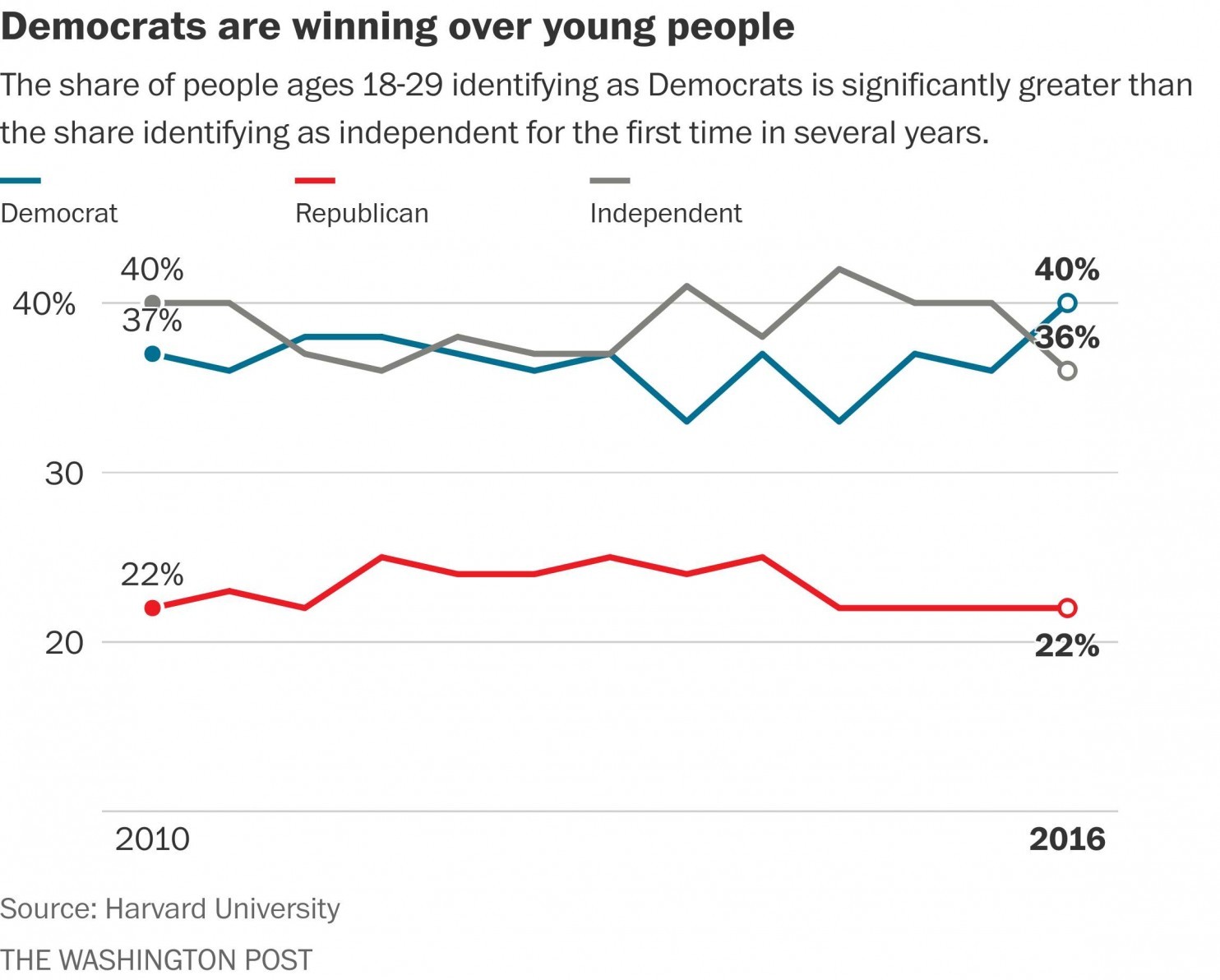

For the first time in the past five years of Harvard's polls, significantly more young people called themselves Democrats than said they were independent. Forty percent were Democrats, 22 percent were Republicans and 36 percent were independent.

On the trail, Sanders has railed against what he called "casino capitalism," calling himself a "democratic socialist." A narrow majority of respondents in Harvard's poll said they did not support capitalism. While just 1 in 3 said they supported socialism, the figures are still an indicator of millennials' frustration with the U.S. economic system, Della Volpe said.

He called it "a lack of trust that young Americans have," a distrust that extends to "the very premise of how our country's organized."

The millennial generation has no universally accepted definition, but one point of departure is the Census Bureau's projection that by 2020, 36 percent of eligible voters will be adults born after 1980.

Young people don't vote as much as older people, to be sure. Just 41 percent of those between the ages of 18 and 24 turned out in the last presidential election in 2012, compared with 72 percent of those older than 65. Yet as these millennial voters grow older, pollsters expect that they will begin voting more frequently, and their opinions will carry increasing weight in elections.

Della Volpe cautions that it's impossible to predict how millennials' views will shift in the future, but people change parties only rarely after about age 30, researchers have found. If that pattern holds for the millennial generation, then Democrats could be indebted for decades to a politician who has rejected a formal association with the Democratic Party for his entire career until now.

In Harvard's poll, Sanders was the clear favorite of young people. Fifty-four percent said they had a favorable view of him, and 31 percent said they had an unfavorable view.

With respect to Hillary Clinton, 53 percent had an unfavorable view, and 37 percent said their views of the former secretary of state were favorable. Her gender does not seem to be helping her among young people: even self-identified millennial feminist women in the Harvard poll say that Sanders would do the most to improve women's lives in the United States, Della Volpe pointed out.

Millennials' opinions of Donald Trump, by contrast, are decisively negative. Seventy-four percent said they view the Republican front-runner unfavorably, including 57 percent of young Republicans. By contrast, 52 percent of the poll's respondents viewed Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) unfavorably, including just 30 percent of millennial Republicans. Among that group, 56 percent had a favorable view of Cruz.

The data raise a couple of questions about the future of the Democratic Party.

There are some moderate Democrats who argue that a more liberal agenda is unlikely to succeed, both politically and in practice. They've been pushed to the margins in this primary campaign, as both Clinton and Sanders have competed to establish themselves as liberal stalwarts. The poll suggests that as millennials vote in increasing numbers over the next several election cycles, they could pose another obstacle for moderate Democrats seeking to reestablish their position in the party.

In the long term, a major question will be whether these young people newly identifying as Democrats will remain loyal to the party. If so, then today's millennial liberalism has the potential to create a small but lasting numeric advantage for Democrats.

To some degree, the increase in millennial identification with the Democrats could reflect Clinton's efforts, along with young people's antipathy toward Trump, the Republican front-runner. Yet Della Volpe said Sanders's evident popularity deserves much of the credit.

"That's not all him, but there is no question that there is a significant part of the electorate that he has woken up and is organizing," Della Volpe said.

[Max Ehrenfreund writes for Wonkblog and compiles The Washington Post's Wonkbook, a daily policy newsletter. You can subscribe here. Before joining The Washington Post, Ehrenfreund wrote for the Washington Monthly and The Sacramento Bee. Follow @MaxEhrenfreund .]

Spread the word