Scott Walker was under pressure. It was September 2011, and earlier that year the first-term governor had turned himself into the poster boy of hardline Republican politics by passing the notorious anti-union measure Act 10, stripping public sector unions of collective bargaining rights.

Now he was under attack himself, pursued by progressive groups who planned revenge by forcing him into a recall election. His job was on the line.

He asked his main fundraiser, Kate Doner, to write him a briefing note on how they could raise enough money to win the election. At 6.39am on a Wednesday, she fired off an email to Walker and his top advisers flagged “red”.

“Gentlemen,” she began. “Here are my quick thoughts on raising money for Walker’s possible recall efforts.”

Her advice was bold and to the point. “Corporations,” she said. “Go heavy after them to give.” She continued: “Take Koch’s money. Get on a plane to Vegas and sit down with Sheldon Adelson. Ask for $1m now.”

Her advice must have hit a sweet spot, because money was soon pouring in from big corporations and mega-wealthy individuals from across the nation. A few months after the memo, Adelson, a Las Vegas casino magnate who Forbes estimates has a personal fortune of $26bn, was to wire a donation of $200,000 for the cause.

Adelson’s generosity, like that of most of the other major donors solicited by Walker and crew, was made out not to the governor’s own personal campaign committee but to a third-party group that did not have to disclose its donors. In the world of campaign finance, the group was known as a “dark money” organisation, as it was the recipient of a secret flow of funds that the public knew nothing about.

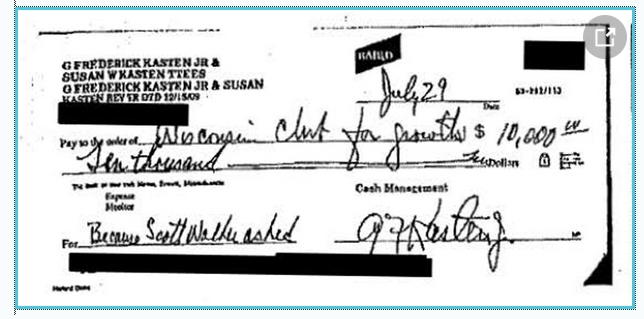

One of the checks made out to the group, for $10,000, came from a financier called G Frederick Kasten Jr. In the subject line of the check, Kasten had written in his own hand: “Because Scott Walker asked”.

Because Scott Walker asked. That could stand as an elegant catchphrase for the state of democracy in the US today, where elections are lost or won as much according to candidates’ ability to attract corporate cash as by the strength of their leadership or ideas.

The phrase is to be found within a batch of 1,500 pages of leaked documents obtained by the Guardian that are being published in their entirety for the first time. The cache consists of a stack of evidence gathered by official prosecutors in Wisconsin who were conducting what was called a “John Doe investigation” into suspected campaign finance violations by Walker's campaign and its network.

The John Doe files published today open a door onto how modern US elections operate in the wake of Citizens United, the 2010 US supreme court ruling that unleashed a flood of corporate money into the political process. They speak to the mounting sense of public unease about the cosy relationship between politicians and big business, and to the frustration of millions of Americans who feel disenfranchised by an electoral system that put the needs of corporate donors before ordinary voters.

The John Doe files

The Guardian has obtained 1,500 pages of leaked documents assembled by Wisconsin prosecutors in the course of their John Doe - ie anonymous - investigation into alleged campaign finance violations in Wisconsin. They include legal filings held under seal and email exchanges between Scott Walker, his team of advisers, and rightwing lobby groups who support the governor and his anti-union agenda.

The theme has become a rallying cry in the US presidential election. Bernie Sanders accused politicians – not least his Democratic rival Hillary Clinton – of selling themselves to Wall Street and special interests.

Donald Trump went further, brazenly using himself as an example of a billionaire who has put politicians in his pocket. “When you give to them,” he said in a confessional tone during a televised Republican debate in the run-up to the primaries, “they do whatever the hell you want them to do.”

According to the independent monitoring group, the Center for Responsive Politics, $2bn of corporate cash has been lavished on the presidential race so far. It’s a bewildering figure, but it only tells us so much about how the new American democracy works in practice, because so much of that largesse is shrouded in secrecy.

Donors are often undisclosed, campaign finance laws are notoriously complicated, and scrutiny by electoral authorities is rare, prosecutions even rarer. When official investigations are launched, they often flounder before reaching a conclusion and virtually never have the chance to reveal their findings to the public.

It is into that dark and obscure post-Citizens United world that the John Doe files leaked to the Guardian land. These are the documents that some of the most powerful judges in the country tried to stop the public from ever seeing.

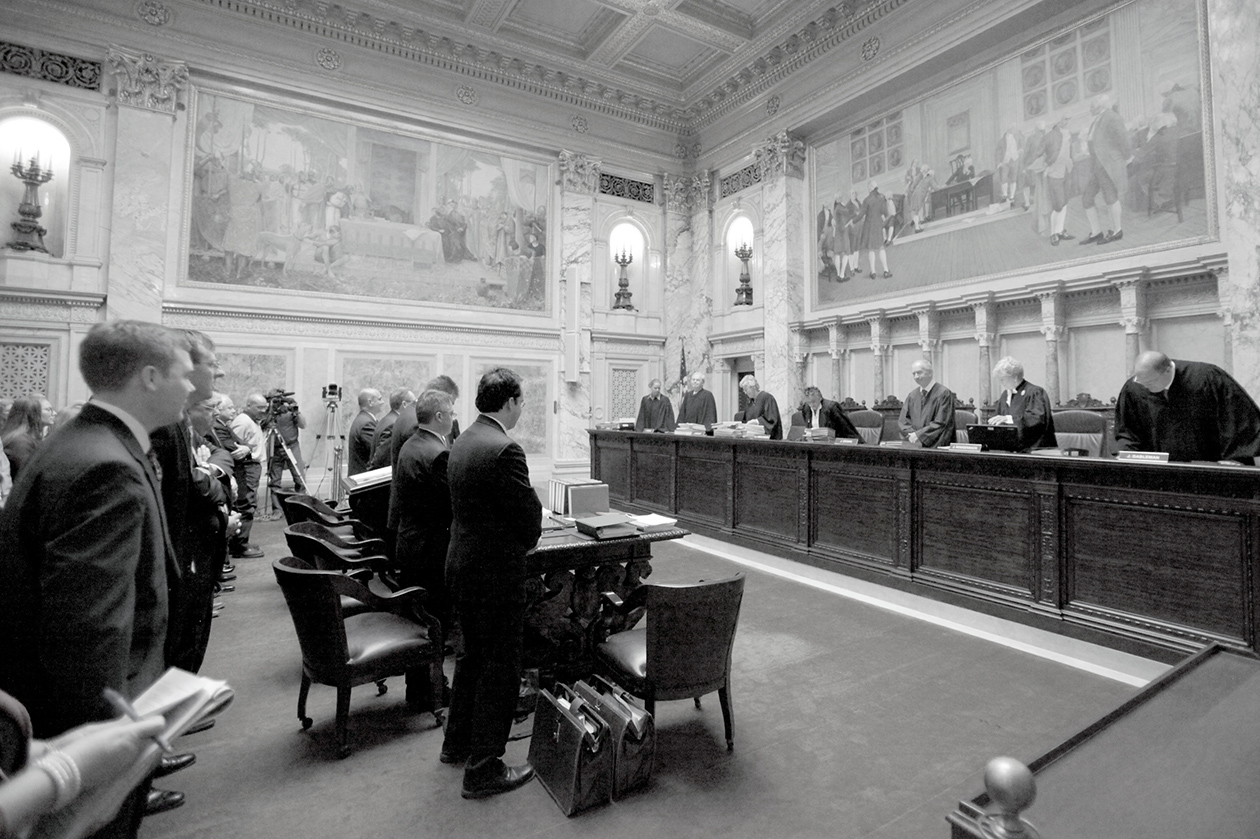

In July 2015 the state's highest court, the supreme court of Wisconsin, terminated the John Doe investigation before any charges were brought. The conservative majority of the court ruled that the prosecutors had made a basic misreading of campaign finance law and targeted individuals who were “wholly innocent of any wrongdoing”.

In a contentious twist to the ruling, the justices ordered the prosecutors to “permanently destroy all copies of information and other materials obtained through the investigation”.

This latter-day equivalent of a book burning could have condemned the John Doe investigation into permanent oblivion, leaving voters none the wiser. But at least one copy of the evidence gathered by the prosecutors survived the bonfire, and have now been leaked to the Guardian.

Protesters rally inside the Wisconsin state capitol on 23 February 2011 against an anti-union bill proposed by Governor Scott Walker. Photograph: Carlos Ortiz/EPA

Snippets of the documents have already seen the light of day, quoted in legal filings, some of which were mistakenly posted to an official website. But the Guardian’s documents – consisting of email exchanges between Walker, his advisers, Republican leaders and major donors who included none other than Trump himself, together with court filings held under seal – amount to a rich chronicle of the electoral health of the United States in the wake of Citizens United.

They also form the substance of a case currently before the US supreme court, which has been petitioned by the Wisconsin prosecutors in an appeal against the decision to shut down their investigation. The nation’s highest judicial panel is expected to announce within days whether or not it will take the case.

Citizens United, explained

For more than 60 years, it was an explicit federal rule that profit-making corporations were not allowed to intervene directly in elections. Then along came Citizens United v FEC, the US supreme court's highly contentious 2010 decision.

The ruling gave corporations - and by extension labor unions - the same first amendment rights to free political speech as any human being.

It opened the floodgates for corporate cash to pour into elections. Coupled with the related ruling, Speechnow.org v FEC, it spawned Super Pacs that can spend unlimited amounts of corporate money on trying to sway votes.

Since 2010 Super Pacs have become a fixture of the political landscape, as have so-called "dark money" groups that channel undisclosed donations.

At the heart of the John Doe files is Scott Walker, the governor who shot to national prominence – a hero for conservatives, pariah for liberals – soon after taking office in February 2011 when he introduced the hyper-partisan Act 10. The legislation instantly made Wisconsin the battleground state in the fight between boardroom might and union muscle.

The state capital Madison erupted in weeks of protests in which the legislative building was overrun with thousands of protesters. Democratic lawmakers fled the state and took up residence in neighboring Illinois in a failed attempt to foil Walker's plans.

In the fallout of Act 10, progressive groups retaliated by dragging Walker and several other Republicans through a series of bitter recall elections. Six GOP senators were forced to defend their seats in 2011, and Walker himself was put through the recall furnace in 2012.

Those recall elections, and the question of whether Walker flouted campaign finance regulations in order that he and other Republican politicians could stay in office and preserve their anti-union legislation, were the focus of the investigation that generated the files now leaked to the Guardian. It was run by five Wisconsin prosecutors, led by Francis Schmitz, a former federal counter-terrorism expert.

It was known as a John Doe investigation because, much like a grand jury, its subjects were kept anonymous while officials weighed whether or not to press charges. In this case, prosecutors alleged that there was evidence to indicate that Walker and his team of advisers and associates had set up a coordinated effort with lobbyists and major donors to swing elections by secretly pouring huge amounts of corporate cash into the races.

The money was channeled through a third-party group, the DAs alleged, in order to circumvent state and federal rules that set limits on political contributions and require them to be publicly revealed.

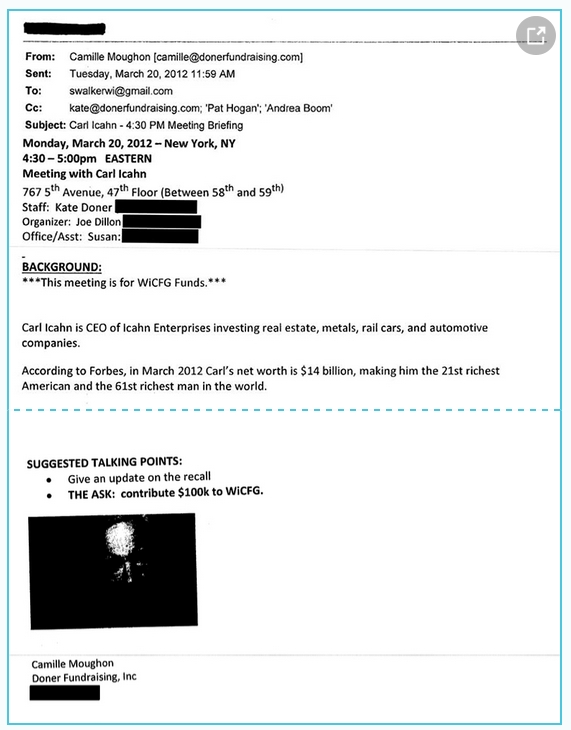

The documents show the governor and his fundraising team going after, and receiving cash from, many of the most prominent rightwing donors in the country. In addition to Adelson, there was business magnate Carl Icahn who was approached for $100,000 though nothing in the files indicates that he donated; the hedge-fund billionaire Stephen Cohen, who arranged a wire transfer of $1m; and Home Depot co-founder Ken Langone who gave $25,000.

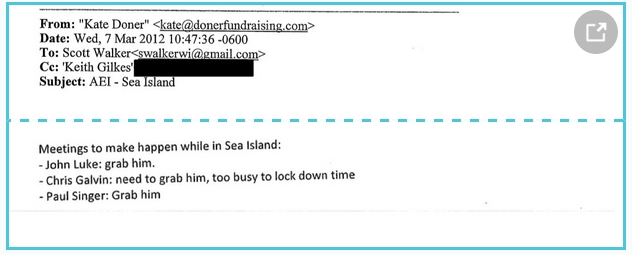

Paul Singer, hedge-fund manager and chairman of the Manhattan Institute, also crops up in the documents. Three months before Walker's recall election, Singer attended a forum of business leaders held by the American Enterprise Institute in a luxury resort off the coast of Georgia.

Walker was also there, arriving at the resort armed with a to-do list from his chief fundraiser Kate Doner. It bore the pithy command: “Paul Singer: Grab him”.

The governor presumably did as he was told. Two months later a check from Singer was banked for $250,000.

What particularly caught the attention of the prosecutors was that when the money came in it did not go directly to Walker's personal campaign committee, Friends of Scott Walker. To do so would have been problematic, as any campaign committee directly linked to a candidate is limited in Wisconsin to accepting contributions of up to $43,000 that have to be fully disclosed.

The prosecutors alleged in court filings published here for the first time that Walker's campaign found a way around these restrictions by banking the corporate cash through the third-party group, Wisconsin Club for Growth. WCfG describes itself as a “pro-liberty, pro-fiscal restraint” organisation, sharing the same small government and anti-union ideology as Walker. It is a tax-exempt group, or 501 (c) (4), that is supposed to be primarily concerned with “social welfare” rather than partisan politics and as such is not obliged to reveal its donors.

Top: The American Enterprise Institute, a rightwing thinktank, holds its annual 'World Forum' at Sea Island, a luxury resort off the coast of Georgia. Bottom: Scott Walker introduces Donald Trump at a rally in West Bend, Wisconsin. Photographs: Carlos Ortiz/EPA, Darren Hauck/Getty

In court submissions, the prosecutors alleged that Walker's campaign used WCfG as a shadow committee that allowed him to solicit large sums of corporate cash without scrutiny or accountability. “Contributions were personally solicited by Governor Scott Walker to WCfG ... in order to circumvent the reporting and contributions provisions of Wisconsin statutes,” an investigator working for the prosecutors in the John Doe investigation, Robert Stelter, alleged.

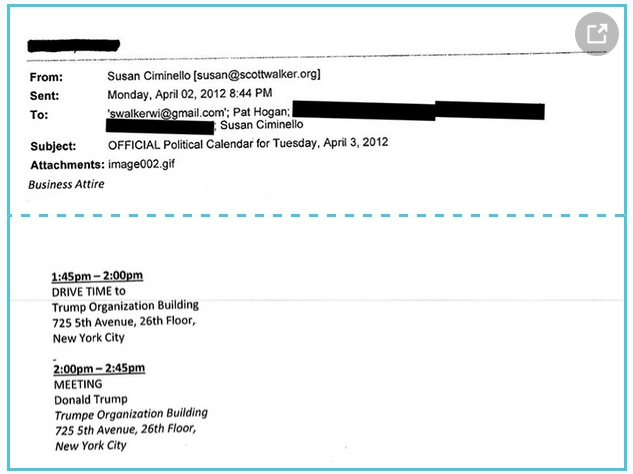

A good example of the way things worked was the donation made by Donald Trump. On 3 April 2012, two months before the governor faced the electorate, Walker flew to New York for a rapid-fire string of fundraising meetings with big money interests.

He travelled the length of Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, making stops at the investment bank Morgan Stanley, a hedge fund, a corporate law firm, and the residence of publishing tycoon Steve Forbes. He also enjoyed a 45-minute audience with Trump in his Fifth Avenue lair.

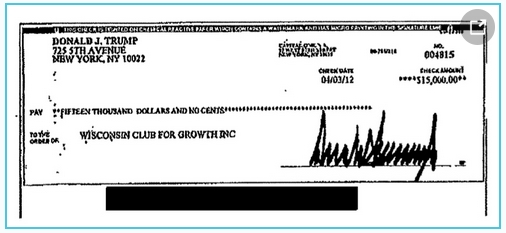

There is no record of the conversation between the two men. But it appears to have been a warm encounter, as the John Doe files show that Trump wrote a check for $15,000 on the same day. Who was the beneficiary of Trump's generosity? Wisconsin Club for Growth.

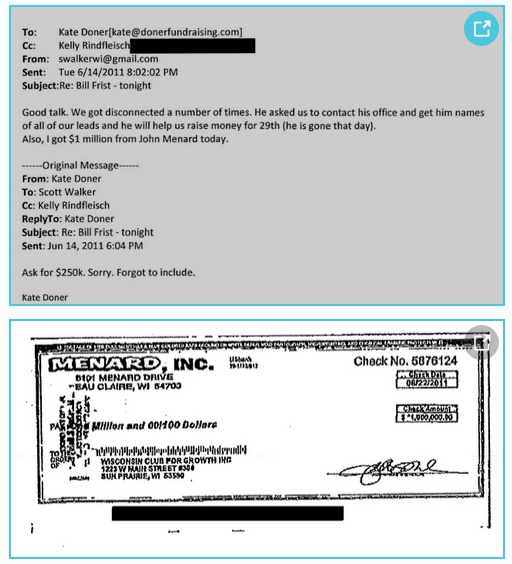

Another example of the pattern is the casual comment Walker dropped into an email to his fundraiser dated 14 June 2011: “Also, I got $1m from John Menard today”. Eight days later a check for $1m is cut on a corporate check of Menard Inc, the billionaire John Menard's home improvement chain Menards, and made out not to the governor's campaign committee but to Wisconsin Club for Growth. There the donation remained a secret until the publication of the Guardian's leaked files.

Friends of Scott Walker, Wisconsin Club for Growth and other parties named in the John Doe investigation have all vigorously denied any legal violations. They point out that no charges have been brought against any subject of the inquiries.

John Fadness, spokesman for the Scott Walker campaign, told the Guardian: “As widely reported two years ago, the prosecutor’s attorney stated that Governor Walker was not a target. Several courts shut down the baseless investigation on multiple occasions, and there is absolutely no evidence of any wrongdoing.”

In June 2014, the special prosecutor Schmitz said through a lawyer that Walker was not a target of his John Doe investigation. Yet legal documents contained in the John Doe files identify as the anonymous “Movant No. 1” of the investigation “Friends of Scott Walker, the personal campaign committee of Scott Walker.”

David Rivkin, the attorney representing Wisconsin Club for Growth and its director Eric O'Keefe, said in a statement to the Guardian: “As the Wisconsin Supreme Court explained, the John Doe prosecutors made up crimes 'that do not exist' under Wisconsin law in order to target 'citizens who were wholly innocent of any wrongdoing.' Because the U.S. Supreme Court does not review matters of state law, it should be obvious that the John Doe prosecutors' appeal is legally frivolous and just another publicity stunt intended to tarnish their targets' reputations and salvage their own.”

Further insight into the position of the subjects of the investigation – the “movants” as they are technically known – is given in court papers including in the Guardian's John Doe Files. They criticise the prosecutors for making fundamental mistakes in their reading of campaign finance law. They said that regulatory restrictions on the size and source of donations only applied to groups that were expressly advocating for or against a named political candidate.

WCfG's director Eric O'Keefe said in an affidavit that the club's involvement had stemmed purely from its commitment to “advancing liberty and fiscal responsibility”. Its role in the recall elections was “to educate Wisconsin citizens ... The Club paid for advertisements that advanced its pro-liberty, fiscal responsibility, pro-Act 10 beliefs. None of the advertisements expressly urged voters to vote for or against any candidate.”

The movants also complained that in issuing over-broad subpoenas for evidence and conducting pre-dawn raids on the homes of some individuals, the prosecutors strayed well beyond their legitimate powers and into the realm of governmental abuse.

In the course of the John Doe investigation, the prosecutors obtained hundreds of emails and bank records under subpoena. An email sent by Kate Doner, Walker’s fundraiser, in April 2011, summed up the strategy. She said the aim was to raise $9m in six weeks, to pay for political advertising – she called it “issue advocacy efforts” – in the senatorial recall races.

Walker, she said, wants all the ads “run thru one group to ensure correct messaging”, and that group, the governor declared, should be Wisconsin Club for Growth. “The Governor is encouraging all to invest in the Wisconsin Club for Growth can accept Corporate and Personal donations without limitations and no donors disclosure.”

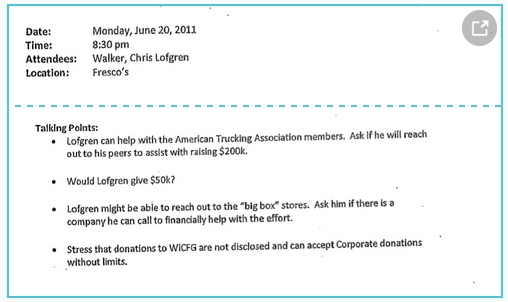

The email trail shows a pattern of behavior developing: Walker meets up with big corporate donors and encourages them to contribute unlimited sums of money through WCfG in secret, then shortly after the checks start to flow. In June 2011, the emails show, the governor had dinner with the CEO of the largest privately owned trucking company in the US, Schneider National, in the hope of getting him and his peers to donate $250,000.

“Stress the donations to WiCFG are not disclosed and can accept Corporate donations without limits,” Walker's talking points said.

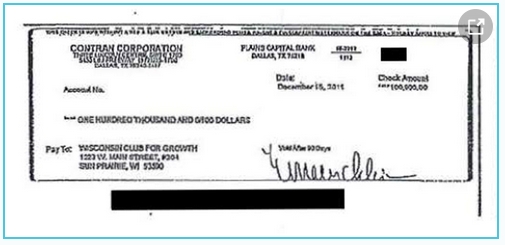

Two checks are recorded in the John Doe files from Schneider, both made out to WCfG and totalling $65,000.

The Schneider checks, like several others included in the files, were cut on corporate checks in the name of the company itself. It has long been a rule under Wisconsin state law, commonly known as the “corporate ban”, that corporations are not allowed to make direct political donations; they are only allowed to fund third-party groups that have to be fully independent of candidates, or spend money themselves on political TV advertising so long as the expenditure is declared.

Some of those checks are published by the Guardian today, redacted to remove bank numbers. The Guardian has also redacted other documents in the files to remove personal information such as cellphone numbers and private home addresses. Personal email addresses have also been redacted unless they have already been put into the public domain, as in the case of Scott Walker's own personal email address.

The John Doe files reveal that Walker's own advisers reached the conclusion that the large sums flowing into WCfG's coffers from corporate donors was critical to the survival of the Republican senators in their recall elections. In a memo sent to Walker shortly after the elections in August 2011, his former top campaign consultant RJ Johnson looked back on the contest and ruminated that “Our efforts were run by Wisconsin Club for Growth ... who coordinated spending through 12 different groups. Most spending by other groups was directly funded by grants from the Club.”

He went on to note that WCfG “raised 12 million dollars and ran a soup to nuts campaign ... Polling, focus groups and message development was a collaborative effort.” A mass of micro-targeted mail-outs and TV advertising that was bought with the donations had the impact that they “moved independent swing voters to the GOP candidate”.

Governor Scott Walker had numerous meetings and phone calls with big corporations and super-wealthy donors over the course of 2011 and 2012 when he and his fellow Republicans in the state senate were facing recall elections. Large donations often followed, with many of the checks being made out to the conservative lobby group Wisconsin Club for Growth, which prosecutors alleged was working in coordination with Walker's personal campaign committee.

Meeting:

In person/By phone/Meeting with Walker campDonation to WCfG/Who | Title | DateFrom | Amount | DateDick and Liz Uihlein | Founder, Uline and wife | 17 May 2011Richard Uihlein | $50,000 | 11 Aug 2011Jon Hammes | Founder, Hammes Company | 17 May 2011HF Securities LLC | $25,000 | 28 Jul 2011Ted Kellner | CEO, Fiduciary Management | 17 May 2011Ted D. or Mary T. Kellner | $100,000 | 10 Jun 2011Chris Lofgren | CEO, Schneider National | 20 Jun 2011Schneider Enterprise Resource LLC | $25,000 | 12 Jan 2012Larry Nichols | CEO, Devon Energy | 31 Jan 2012Devon Energy Production Company, L.P. | $50,000 | 3 May 2012David Herro | Republican donor | 9 Feb 2012David G. Herro | $6,000 | 11 Feb 2012David G. Herro | $25,000 | 12 Apr 2012Dave Hanna | CEO, Atlanticus Holdings | 24 Feb 2012David William Hanna Trust | $50,000 | 27 Feb 2012Annie Dickerson and Dan Senor | Advisers to Paul Singer | 8 Apr 2011Paul Singer | $500,000 | 1 Jul 2011Paul Singer | $250,000 | 8 May 2012Barry MacLean | CEO, MacLean-Fogg | 11 Mar 2012Barry and Mary Ann MacLean | CEO, MacLean-Fogg and wife | 20 Apr 2012MacLean-Fogg Company | $100,000 | 14 May 2012Donald Trump | Businessman | 3 Apr 2012Donald J. Trump | $15,000 | 3 Apr 2012John Roberts | CEO, JB Hunt | 3 Apr 2012J B Hunt Transport | $10,000 | 5 Jun 2012Ken Langone | Founder, Home Depot | 10 Apr 2012Kenneth G. Langone | $15,000 | 10 Apr 2012Keith Colburn | CEO, CED | 20 Apr 2012Keith Colburn | $25,000 | 24 Apr 2012Richard Colburn | Board member, CED | 20 Apr 2012Richard W Colburn | $50,000 | 7 May 2012Stacy Schusterman | CEO, Samson Investment Company | 27 Apr 2012Stacy H Schusterman | $10,000 | 1 May 2012

The collaboration set up in 2011 was successful in helping four of the six Republican senators fend off the recall challenge and keep their jobs – allowing them to hang onto their senate majority by one vote. Act 10 was safeguarded for the moment, and in a gesture of gratitude Walker himself was moved to ask an aide shortly after the vote: “Did I send out thank you notes to all of our c(4) donors?”

Supporters of Governor Walker and the outside groups that worked with him, including some prominent media outlets such as the Wall Street Journal, argue that the prosecutors were mistaken in their view that the coordinated activities amounted to a violation of campaign finance law. They point out that nobody in the governor's circle has been charged with any alleged violation relating to the recall elections, and argue that WCfG and the other outside groups engaged in advocacy over issues related to the elections, which is not subject to restrictions, as opposed to express advocacy on behalf of one political candidate or another.

They also insist, using a complex formula related to the electoral calendar, that Walker only became an official candidate on 9 April 2012. Any actions he and his associates took before then were not subject to restrictions, they argued. To which the prosecutors replied that Walker's campaign committee had been frantically fundraising and coordinating long before that date.

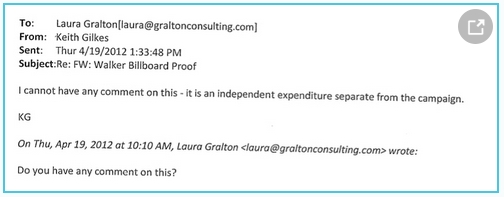

The John Doe files do contain some evidence that Walker's senior team attempted to maintain a firewall between candidate and outside interests after that date. On 19 April, the lead adviser to the governor's recall campaign, Keith Gilkes, replied to a group of businesses wanting to put up billboards supporting Walker's candidacy: “I cannot have any comment on this – it is an independent expenditure separate from the campaign.”

But the files also contain documents that show that RJ Johnson, a prominent political strategist in Wisconsin who worked closely with Walker for many years, and Johnson's business partner Deborah Jordahl, were simultaneously arranging political ad spending on TV and radio for both Walker's campaign and the outside lobbying groups. On 23 April 2012 Johnson emailed Gilkes about a Walker ad that he was putting out for the recall election; a week later Johnson and Jordahl were emailing each other about radio ad spending on behalf of Wisconsin Club for Growth.

That lead the special prosecutor, Francis Schmitz, to conclude that “a review of email reflects that RJ Johnson ... was involved in the media buys on behalf of Wisconsin Club for Growth and Friends of Scott Walker.”

Neither RJ Johnson nor Deborah Jordahl immediately responded to requests for comment.

Until the US supreme court indicates later this month whether or not it will intervene in the John Doe case, the question of the legality of the Walker network and the coordination that it involved will hang in the balance. The Wisconsin supreme court was firm on the issue: in its July 2015 ruling, the court castigated Schmitz for instigating a “perfect storm of wrongs that was visited upon the innocent Unnamed Movants and those who dared to associate with them.”

In colorful language, the state's highest court praised Walker, WCfG and other movants in the investigation (it didn't name them, but their identities are self-evident from the John Doe files as “brave individuals”. It said they had “played a crucial role in presenting this court with an opportunity to re-endorse its commitment to upholding the fundamental right of each and every citizen to engage in lawful political activity and to do so free from the fear of the tyrannical retribution of arbitrary or capricious governmental prosecution.”

For good measure, the court added: “Let one point be clear: our conclusion today ends this unconstitutional John Doe investigation.”

That point is certainly clear, unless the US supreme court, which has the final say in any matter of constitutional law, decides otherwise. The nation's highest court has been asked to take the prosecutors' petition by an alliance of campaign-finance monitoring groups, the Center for Media and Democracy, the Brennan Center and Common Cause.

In their petition, the prosecutors ask the US supreme court justices to consider whether Wisconsin's top judicial panel was truly objective in reaching its decision to shut them down. “Is the state as a litigant in an adversary proceeding entitled to a hearing before a panel of impartial justices, free of bias?”, the prosecutors ask.

Protecting Walker's agenda

The John Doe files obtained by the Guardian give clues as to why the prosecutors have raised doubts about impartiality in the state courts. They suggest that two of the conservative judges on Wisconsin's top court who voted to halt the John Doe investigation may have themselves been intimately connected to the same campaigning network of rightwing politicians, lobbyists and major donors that the prosecutors were investigating.

Take David Prosser. He was one of the four conservative judges who approved the July 2015 ruling that terminated the John Doe investigation, sacked Schmitz from his position as special prosecutor and ordered the destruction of all the documents that had been collected (later that order was softened a little to a demand that the prosecutors hand in all the documents to the court which would keep them secret under seal).

At precisely the same time as the six Republican senators were embroiled in their recall election, Prosser was in his own electoral fight for survival. He was up for re-election in April 2011 and facing a tough challenge from JoAnne Kloppenburg, then Wisconsin's assistant attorney general. The Prosser election and the recall election were intertwined in that Kloppenburg was attempting to turn her battle against Prosser into a referendum on Governor Walker's anti-union legislation, Act 10.

Among the leaked John Doe files that the Wisconsin supreme court ordered to be suppressed are documents that underline how anxious Walker's circle were about the threat, as they saw it, to the court's conservative majority. In an email dated 14 December 2010, WCfG's director Eric O'Keefe says he's been in touch with Diane Hendricks, the owner of a roofing company who Forbes describes as America's richest self-made woman with a personal fortune of $5bn. Hendricks is a well-known funder of rightwing causes and individuals, among them Scott Walker himself who she was to go on to support with $500,000 in 2012 for his own recall election.

Judge David Prosser faced a tough re-election battle to remain on the seven-justice Wisconsin Supreme Court. Photograph: M.P. King, State Journal/AP

Hendricks has also popped up as part of the Donald Trump presidential campaign. Trump recently added her to his inner team of economic advisers, having come under fire for only appointing men.

“I have traded emails with diane hendricks,” O'Keefe says in the email. “She is concerned about the state s. Ct.”

Hendricks was right to be concerned about the state supreme court. Were Prosser to lose the vote, the consequences for Walker and his entire rightwing union-bashing agenda would have been devastating. The four-to-three, conservative-to-liberal, balance of the state's top court would have been reversed, allowing progressive groups to overturn the reforms through legal challenges.

The correspondence reveals how Walker's network of associates vowed to go to work to keep Prosser in his job, and thus preserve (or “maintain”) the court's conservative upper hand. “It would be good for to talk with us or have her see our plan,” writes RJ Johnson, the then “general consultant” to Governor Walker's campaign committee. He says that WCfG “is leading the coalition to maintain the court. Thus far I have raised 450k and am looking to raise an additional 409k.”

Johnson name-checks other sources of big money donations that he intends to tap. Leo Leonard of the conservative legal group the Federalist Society was looking for an extra $200,000, he says, and there were hopes for a further $1m from the US Chamber of Commerce.

He wasn't bragging. As election day approached, money from rightwing lobby groups and corporations began to pour into Wisconsin, unseen by the public, as the message got out that Prosser's salvation was a necessary step to safeguarding Walker's radical rightwing reforms and Act 10.

An email from March 2011, just two months after Walker took office as governor and a month before Prosser was tested at the polls, makes the point. It's from Matt Seaholm, state director of Americans For Prosperity (AFP), the Tea Party-affiliated group founded and funded by the billionaire rightwing Koch brothers.

By now the anxiety surrounding the fate of the Wisconsin supreme court judge, David Prosser, is growing more intense. “This could stop everything that Walker is trying to accomplish and [the unions] know it. Goes without saying, that would be a bad thing,” Seaholm says, writing to Tim Phillips, AFP's national president.

By 20 March, two weeks before the election, worry is distilling into panic. Brian Fraley of the Wisconsin-based conservative think-tank the MacIver Institute, shoots an impassioned plea for help to what he calls his “group” of like-minded lobbying groups and individuals, forwarded to Walker's chief of staff and other top advisers in Madison.

“David Prosser is in trouble,” Fraley begins. “And if we lose him, the Walker agenda is toast, as could be the Senate GOP majority and any successes creating a new redistricted map. That's not hyperbole.”

By the end of the bitter campaign, some $3.5m was spent by outside lobby groups channeling undisclosed corporate money to support Prosser's re-election – more than eight times the $400,000 the judge was allowed to spend himself. That included $1.5m from WCfG and its offshoot Citizens for a Strong America, and $2m from Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce (WMC), all of it in unaccountable “dark money”.

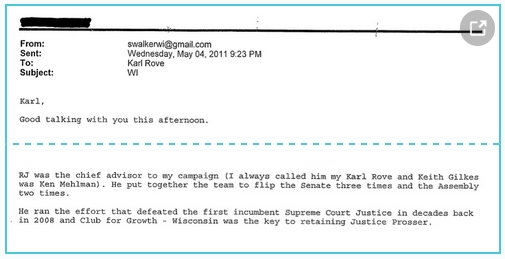

It worked. Prosser was re-elected, with a squeaky-tight margin of just 7,000 votes and after a fraught recount. The following month, Walker boasted to the Republican kingmaker, Karl Rove, “Club for Growth–Wisconsin was the key to retaining Justice Prosser.

Act 10 was safe.

Both of the two outside groups that channeled the recall election money (WCfG and WMC) are named as “movants” of the John Doe criminal investigation into alleged campaign finance violations that was shut down under the court ruling that Prosser, having won re-election in no small part with their help, joined. Yet when it was suggested to Prosser and a second conservative judge on the court, Justice Michael Gableman, that they should recuse themselves from deliberations in the case, they both refused.

In their petition to the US supreme court, the prosecutors challenge that refusal, arguing that “the special prosecutor did not receive a fair and impartial hearing”. The petitioners go on to discuss Prosser in detail, but the passage is so heavily redacted that their argument is obscured. They do say at one point, quoting constitutional law, that “No jurist 'can be a judge in his own case or be permitted to try cases where he has an interest in the outcome'.”

Prosser declined to step aside citing a rule change that had been suggested and partially written by WMC itself. The change removed the obligation of supreme court judges in Wisconsin to recuse themselves in cases involving groups that had helped them secure their own elections.

Kurt Bauer, WMC's president and CEO, declined to comment on the John Doe proceedings. But he stressed that the organization's “grassroots lobbying activities are conducted carefully within both the letter and the spirit of the state law. WMC strongly disputes any allegations of wrongdoing and will vigorously defend itself against such allegations.”

Bauer added that WMC was an independent group that was not controlled by any candidate or candidate’s campaign. “WMC will not allow itself to be silenced from commenting about public officials and public policy. WMC has long been a proponent of the First Amendment and has a history of fighting to protect its ability to publicly express its views. WMC maintains that commitment to protecting its right to express a point of view on public policy, public officials and candidates for office as well as protecting the confidentiality of its donors.”

In a telephone interview with the Guardian, Prosser, who retired from the state supreme court in July, said that in his view sufficient time had passed between his re-election in 2011 and the judgment in the John Doe case in 2015 for any potential conflict of interest to fade. “If this had been a year after the contributions I think I would have had to withdraw, but it was four years. There was no expectation on the part of recipient or givers that the contributions were designed to effect litigation, and so the contributions raised no questions whatsoever.”

Prosser said that at the time of his re-election he was facing hostile TV ads that falsely tried to link him to Walker's contentious anti-union legislation Act 10, while he himself was unable directly to solicit large amounts of campaign contributions under new strict fundraising limits imposed by an earlier Democratic-controlled legislature. “I certainly expected Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce sooner or later to put some money into my campaign. Of course I was going to hope that somebody would come in and defend me because I was unable to defend myself.”

But the judge stressed that the only spending involved came from "third parties in which no one on my campaign knew they were coming, didn't ask for them, and frankly if they hadn't come I would have been blown out of the water by false advertising”.

Last year Prosser issued a 12-page justification of his refusal to recuse himself from the John Doe case. In it, he made reference to an email from an “Unnamed Petitioner” that discussed raising money for a campaign “to maintain the Court”. The judge said the comment was “little more than evidence of the fact that some targets of the investigation ... engaged in expenditures that, under all the circumstances, were very valuable to my campaign.”

Just two weeks before writing that sentence, Judge Prosser had approved the court ruling that ordered the destruction of the John Doe files, among which was to be found the very same email to which he referred. The Guardian now publishes that full email for the first time, and as a result the identity of the anonymous “Unnamed Petitioner” who vowed to “maintain the Court” can be revealed: RJ Johnson, “general consultant” to the governor of Wisconsin, Scott Walker.

Top: An estimated 70-100,000 demonstrators rallied outside the Wisconsin capitol building in February 2011 to protest a bill restricting collective bargaining rights. Bottom: A petition to recall the governor launched in November of that year. Photograph: Scott Olson/Getty, Chicago Tribune/MCT/Getty

Why it matters

So why should we care about today's fiendishly complicated ways of funding elections? After all, isn't it a cornerstone of American democracy that everybody should be able to express themselves, under the first amendment right of free speech, after which the American people gets to have the final say at the ballot box?

One area of possible concern raised by the John Doe files chimes with the anger and disgruntlement of voters that Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have so powerfully articulated in the presidential race. If money channels are set up in secret to allow corporations and the super-wealthy to inject vast amounts of undisclosed cash into political races, the level playing field can be distorted to the benefit of corporate-friendly candidates and to the disadvantage of those representing ordinary voters.

By the end of Scott Walker's recall election, some $81m overall was spent on the battle – equivalent to $23 for every registered voter in the state. The governor and other Republican groups and committees invested $58.7m, while his Democratic rival and supporters were only able to muster less than half that amount, $21.9m.

“The sheer increased volume of corporate money that has been brought into elections in recent years may go more on one side than the other,” explained Richard Briffault, a professor specialising in campaign finance law at Columbia law school. “Corporations tend to lean more Republican.”

Briffault added that the proliferation in the modern era of outside “social welfare” 501 (c) (4) organisations – the tax-exempt status enjoyed by Wisconsin Club for Growth – also raised the possibility that political donations would go hidden. As tax-exempt groups that are supposed not to be primarily political in their orientation, they do not have to disclose their donors.

“That can be a very good device for hiding the participation of wealthy individuals,” Briffault said.

The other great anxiety addressed by campaign finance regulations is the potential for corruption. The US supreme court has said in rulings going back decades that the first amendment right to free speech is tempered by the need to protect against cash-for-favors. The court has repeatedly stated that elected officials must avoid not only the reality of corruption in their dealings with donors, but also any appearance of corruption, because even a suggestion that dollars might have been exchanged for political favors has the ability to undermine public faith in democracy.

The justices use the legalistic phrase: quid pro quo. Literally that means “this for that”; colloquially, it's the idea that if you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours.

Paradoxically, one of the most robust statements made by the US supreme court justices about the dangers of real or apparent quid pro quo was made in Citizens United, their highly contentious 2010 ruling. Citizens United extended to for-profit corporations and labor unions the same first amendments rights to engage in elections that had hitherto been enjoyed by individuals.

Corporations were essentially treated for the first time as though they were people. Together with the related ruling in Speechnow.org, the supreme court paved the way for the creation of Super Pacs that can make unlimited spending on political advertising to help their preferred candidates into office.

What is less well known about Citizens United is that in it, Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the opinion, addressed head-on the fear that unlimited corporate cash would lead to an explosion in real or perceived corruption in the political system. He stated forcefully that there was no danger of corruption if one important condition was met: that corporations kept their distance from the candidates they were supporting and remained fully independent of the candidates' campaigns.

“By definition,” Kennedy wrote, “an independent expenditure is political speech presented to the electorate that is not coordinated with a candidate.” Such separation was necessary, he added, to avoid the risk that unlimited secret donations are given “as a quid pro quo for improper commitments from the candidate”.

The problem is that the US supreme court has never defined in detail what precisely it means by “coordination” between a candidate's campaign and outside groups, preferring to leave the fine print to lower courts and state legislatures. Most of the legal emphasis on coordination is on actual spending on political TV and radio ads, while the other end of the money chain – fundraising by candidates from big corporate donors channeled through third-party “dark money” groups that do not have to disclose their sources of income – is largely unregulated. The lack of firm rules has left players in the election game relatively free to act as they wish – one reason why prosecutions are so rarely brought, or if they are, ever completed.

The outcome of this legal fuzziness is clearly evident in Wisconsin, where the John Doe investigation has been halted before it could even reach a decision on whether or not a full criminal inquiry was merited. That remains the legal standing of the case at present, pending the US supreme court's decision.

But a moral question continues to hang in the air. If, as Kennedy put it, even the appearance of quid quo pro must be avoided to uphold trust in democracy, does the light shone on the modern American way of staging elections by the John Doe files leaked to the Guardian give cause for public concern?

The lead paint mystery

The strange case of lead paint might help answer that question. Lead, as the terrible events of Flint, Michigan, have shown, is a potent poison that can seriously impair the intellectual ability of young children. The Flint health crisis was caused by contaminated water, but another peril to public health is the presence of the toxin in household paint before 1978, when it was banned in the US.

The John Doe files reveal that the billionaire owner of NL Industries, one of America's leading producers of lead used in paint until the ban, secretly donated $750,000 to Wisconsin Club for Growth at a time when Walker and his fellow Republican senators were fighting their recall elections. Also in the same time-frame, the Republican-controlled senate passed, and Walker signed into law, legal changes that attempted to grant effective immunity to lead manufacturers from any compensation claims for lead paint poisoning.

Since the laws were passed, the federal courts have stepped in and overturned key elements of them, leaving NL Industries – or National Lead Company as it was once known – still facing many legal challenges. But the point remains: had the new provisions been allowed to stand, they had the potential to save the company and others like it millions of dollars in damages.

Lawyers working on the lawsuits argue that at stake were the rights of hundreds of children from poor urban areas whose lives were devastated by lead poisoning inhaled from paint when they were growing up. “These children were perfectly innocent. They entered life with all the gifts and health that God gave them and were devastated by this neurotoxin,” said Peter Earle, the principal attorney on 171 cases that are currently ongoing against NL Industries and other former manufacturers of lead paint.

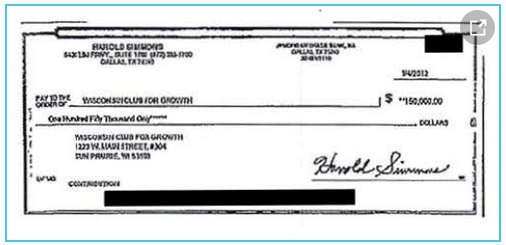

The owner of NL Industries, Harold Simmons, made the undisclosed payments to WCfG in three tranches between April 2011 and January 2012, precisely when the GOP senators and then Walker were facing a fight-to-the-death at the ballot box.

Simmons, who died a year after Walker won his recall election, was a prominent funder of rightwing causes who, along with Donald Trump, was reprimanded by the Federal Election Commission in the 1990s for exceeding legal limits of political campaign contributions. He bankrolled with $3m the notorious Swift Boat smear campaign against John Kerry in the 2004 presidential election that erroneously questioned the current secretary of state's Vietnam war record.

Republicans in the Wisconsin legislature made an initial attempt to change the law on the liability of lead paint producers shortly after Walker became governor. As the name implied, Act 2 was one of his opening gambits that he rammed through the legislature in less than a month after he came to office in January 2011.

One of Act 2's key provisions was to tighten tort law to make it much more difficult for lead victims to sue. Under its terms, anyone injured by lead paint who wanted to issue a new lawsuit had to prove that the company they were taking on was responsible for making the specific paint that was on their walls at the time they inhaled the toxin – a practically impossible task given the number of different manufacturers and the layer-upon-layer of paint on the walls of old houses.

The measure in effect granted immunity to NL Industries and other lead producers from any new claims for compensation.

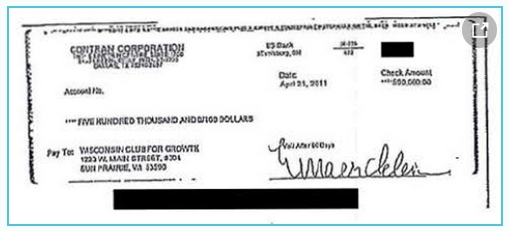

Less than three months after the law was enacted, Simmons arranged for the first and largest check – of $500,000 – to be paid directly from Contran Corporation, his business empire, to Wisconsin Club for Growth. It landed at the time that the six senators were in their recall battles.

Later that year, Walker's interest in soliciting more money from Simmons for use in his own personal recall election is made plain in an email among the John Doe files dated 14 November 2011. It was written by Keith Gilkes, Walker's then senior campaign adviser.

The email was sent just one day before opponents of the governor formally triggered the recall procedure, putting Walker's job on the line. Gilkes rehearsed the names of several wealthy donors to hit up for donations, singling out Simmons and “Sheldon Aldenhouse”, presumably a garbling of the name of Sheldon Adelson, the Las Vegas casino magnate who later donated $200,000 to bolster Walker's recall chances.

The Gilkes memo sets out for Walker some of the “red flags” associated with Simmons and other potential corporate donors “so you are aware of what you might need to defend in terms of contributions from donors when these are disclosed”. He warns Walker that Simmons had a controversial track record for reportedly dumping toxic waste in Texas. Gilkes pointed to an article by Dallas Magazine in which the billionaire was dubbed “Dallas' most evil genius”. The memo also notes that Simmons avoided having to pay millions of dollars in damages to pay for medical treatment for child victims of lead poisoning in Wisconsin's largest city Milwaukee after an appeals court cleared NL Industries of causing a public nuisance and dismissed a lawsuit brought by the city for $52.6m.

The leaked John Doe files do not record what conclusion Walker and his chief adviser reached about Simmons when they discussed him as a potential donor. What the documents do reveal is that only a month later, a second corporate check from Contran Corporation for $100,000 was sent to WCfG.

The third and final check from Simmons for $150,000, also made out to WCfG, was cut the following month from his own personal account.

At this point, the Wisconsin legislature and Governor Walker made a renewed pitch to change the law to the benefit of NL Industries and other historic manufacturers of lead paint. They had already passed Act 2, but that only covered new claims, leaving the company still facing a mountain of lawsuits that were already ongoing.

So the legislators had another go. In the same month as the third check landed, senate Republicans introduced a bill that would make the effective immunity for former lead paint manufacturers retroactive, thereby scuppering all existing lawsuits.

That attempt failed to pass the Wisconsin legislature. But even then the Republican group did not give up. In 2013, after all the recall elections had been fought and won, partly with the benefit of Harold Simmons' support, the legislators tried one more time to pass a bill making the immunity retroactive.

They did so with a great deal of encouragement from NL Industries. Earle, the lawyer acting for victims, has discovered under freedom of information laws that the firm employed a professional lobbyists for 330 hours, at a cost of $172,500, to persuade the Wisconsin legislature to pass the retroactive immunity bill.

Another Foia document shows that NL Industries' lobbyist directly suggested to the Republican leader in the state senate the language that should be added to existing law to make the effective immunity retroactive. The lobbyist encouraged the Republicans to write four words into an amendment that would apply the new immunity protections to all negligence lawsuits “whenever filed or accrued”.

Two months later GOP senators slipped into a budget bill an amendment that contained the same four words proposed by NL Industries: “whenever filed or accrued”. The amendment was introduced after midnight just before the bill was finalized. It can be found by anyone who looks hard enough on page 548 of a 603-page bill that Scott Walker duly signed into law.

NL Industries used the amendment to press for dismissal of the negligence lawsuits it was facing. But the move failed. A federal appeals court stepped in and ruled that such a retroactive granting of corporate immunity was a violation of the US constitution.

Yasmine Clark. Photograph: Courtesy of Xenia Nicole Gee

It is perhaps worth asking what it would have meant for the victims had the amendment stood. Victims like Yasmine Clark, one of the plaintiffs. She suffered such severe poisoning from lead inhaled from residential paint in her home in Milwaukee that she was hospitalized twice, when she was two years old and again when she was five.

When she was at rock bottom, Clark was found to have a lead level in her blood of 48 micrograms per deciliter and had to undergo chelation therapy to remove the toxins. To give a sense of what that meant, doctors in Flint, Michigan, sounded the alarm after children were found to have levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter from polluted water supplies – about one-tenth of Clark's concentration.

Clark's negligence suit, and 170 other cases like hers, are still ongoing against NL Industries and other former manufacturers of lead pigment paint. “They haven't been able to shut me down,” Earle said.

“Yasmine is a victim of egregiously vindictive behavior by these corporations,” the lawyer said. “The idea of freedom in the US is that no matter how poor you are you have the opportunity to surmount those disadvantages, and these lead companies took that opportunity away from her.”

As for Scott Walker, Earle said: “The governor has chosen to ignore the children and instead fought tooth and nail for the corporations that did this. I don't have words to describe that conduct.”

Scott Walker's campaign did not respond to Guardian questions relating to its relationship with NL Industries. NL Industries itself, and Contran Corporation, did not respond to numerous invitations to comment.

As researchers pore over the Guardian's leaked John Doe files, seeking light amid the darkness of today's political process, they may ponder the lead paint mystery. There is no evidence that Wisconsin Republicans led by Scott Walker attempted to change the law as a favor in return for Simmons' $750,000 donation that had helped some of them win their own elections and stay in office. No charges have ever been brought.

But is there even the slightest appearance of quid pro quo? And if potentially there is, should that be a matter that the American people care about? Give the last words to Donald Trump, the presidential nominee of Scott Walker's Grand Old Party: “When you give to them, they do whatever the hell you want them to do.”

Support the Guardian's fearless, independent journalism by making a contribution or becoming a member.

The Guardian US interactive team is Aliza Aufrichtig, Kenan Davis, Jan Diehm, Rich Harris and Nadja Popovich.

Additional research by Lauren Leatherby, Nicole Puglise and Mazin Sidahmed

Spread the word