In 1976, Life magazine marked the US bicentennial with a special report on “Remarkable American Women.” I was thirteen years old at the time and I remember thumbing eagerly through the pages of the magazine, a gift from my mother to nurture my budding feminism.

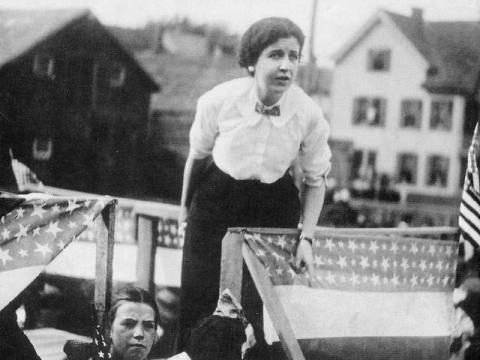

Among the 166 women profiled was the Rebel Girl, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (also known as the IWW or the Wobblies), free speech fighter, co-founder of the ACLU, and first female secretary of the Communist Party USA. Her bio and photo appeared in the section titled “Noble Causes,” along with seventeen other “Crusaders for the Sick, Poor and Oppressed,” including Angela Davis, Dorothy Day, Dolores Huerta, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, and Harriet Tubman.

In 2017, were a magazine of Life’s stature to publish an updated report, Flynn almost certainly would not be deemed worthy of inclusion. That’s too bad, because the Rebel Girl is an especially apt role model for our own times.

As I type these words, Donald Trump and his supporters are celebrating his inauguration as the forty-fifth president of the United States. But while the Trump and Pence families dine and dance, millions of people amassed in Washington, DC and cities around the country and the globe, to answer Trump’s nativism and faux-populism with a demonstration of solidarity and a call for resistance.

Yesterday’s Women’s March is just the beginning of a long process of organizing and protesting in an environment that portends increasing hostility to public dissent. Even before the new president took office, lawmakers around the country began advancing proposals to limit the rights of peaceful protestors. And with the post-inauguration declaration that his would be a “law and order administration,” Trump has made clear which side he is on.

In this era, the example of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is instructive. Throughout her activist career, the Rebel Girl struggled against repressive laws at the local, state, and federal levels and tried to forge a movement of workers that cut across ethnic, racial, and gender barriers. Her efforts, while not always successful, are a wellspring of inspiration for socialists looking to build a movement for genuine social change at the same time we resist the depredations of the Trump administration.

Homegrown Socialist

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was born to a working-class, Irish-American family in Concord, New Hampshire on August 8, 1890. Her parents were committed socialists — the result of firsthand experience with poverty and English colonial rule — and they passed their convictions on to their daughter. The poverty and exploitation Gurley Flynn saw all around her reinforced her inherited politics, engendering in her a hatred of capitalism. The revolutionary philosophy of Marx and Engels, and the socialist orators she heard in her youth, steeled her determination to change the world.

In 1906, at the tender age of fifteen, she was arrested for allegedly blocking traffic in New York City’s Union Square while giving a speech on socialism. It would not be the last time this spellbinder would attract and hold a crowd (nor the last time she would be arrested for doing so).

Working-class audiences loved her. Middle-class intellectuals and bohemians were fascinated by her. Even her critics acknowledged the intellect, eloquence, and spirit of the orator that novelist and journalist Theodore Dreiser christened the East Side Joan of Arc. In public squares and union halls around the country, she inspired countless women and men to join and play an active role in the labor movement with ironclad logic cloaked in effervescent wit.

Flynn became an organizer, or “jawsmith,” for the Industrial Workers of the World in 1906. Founded a year earlier in Chicago with the motto “an injury to one is an injury to all,” the IWW preached a message of solidarity and class warfare to an audience that the more conservative American Federation of Labor (AFL) had chosen to ignore: unskilled or semiskilled laborers, migrants, African and Caribbean Americans, European and Asian immigrants, and women. Saddled with unstable employment, long hours, dismal wages, exploitative working conditions, and no union, these workers were the original precariat.

Partly because so many of its members lacked the franchise, the IWW embraced direct action as the surest way to undermine capitalism and the wage system.

Flynn played a key role in several IWW-led strikes around the US, including the stunningly successful Bread and Roses strike in the textile factories of Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1912. Over the course of ten weeks, 23,000 workers, mostly immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, left their jobs to protest a wage cut.

The strikers’ unity across ethnic lines, the militant action taken by women, the involvement of children, and the use of innovative tactics — such as multilingual mass meetings and mobile picket lines — garnered extensive press coverage, aroused public sympathy, and secured a victory for the strikers, as well as a pay increase for textile workers around the state.

The Free Speech Fights

For all its moxie and organizing skills, the IWW was too loosely structured and its membership too mobile to create viable and enduring unions. But when cities and towns attempted to thwart organizing drives by passing laws that prohibited pro-labor street speaking, the Wobblies parlayed these structural liabilities into assets and fought back.

Flynn played a leading role. She pioneered tactics in Missoula, Montana (1908) and Spokane, Washington (1909) that the union would deploy in similar struggles in other locales, such as Kansas City, Missouri (1911), Fresno and San Diego, California (1910–11 and 1912), and Denver, Colorado (1913).

More than a decade before the founding of the ACLU, Wobblies insisted that the best way to defend free speech was to speak — and they recruited members from across the country to do just that.

Flynn described the process in an address at Northern Illinois University in 1962:

They would send out telegrams . . . and say: “Foot Loose Wobblies, come at once, defend the Bill of Rights,” and they would come on top of the trains and beneath the train, and on the sides, in the box cars and every way that you didn’t have to pay fare, and by the hundreds literally they would land in these communities, to the horror and consternation of the authorities and they would stand up on platforms or soap box and they would read part of the Constitution of the United States or the Bill of Rights.

Hailing passersby with the salutation “Fellow workers and friends!” Wobbly orators claimed street corners, sidewalks, parks, and other urban public spaces, defiantly asserting what French philosopher Henri Lefebvre later called their “right to the city.”

They paid for their defiance of the law with physical violence and verbal abuse from police, monetary fines, and imprisonment. Undaunted, the Wobbly free speech fighters held meetings and sang songs in their prison cells, and demonstrated in front of courtrooms during their comrades’ trials.

As a pregnant nineteen year old, Flynn was arrested and imprisoned for speaking on the street in Spokane. Unlike her male counterparts, who were arrested and jailed en masse, she and a few other women were swept up and held overnight in the women’s jail, without the company of other Wobblies. While there, she wrote an exposé of the deplorable conditions women inmates endured.

Critics of the free speech fights argued that they diverted resources from the union’s primary mission of organizing workers, and by 1916, the IWW had abandoned its civil liberties activism. But the free speech fights still stand as an important chapter in the history of civil liberties in the US, underscoring the vital role radicals have played in defending and expanding democratic rights.

Allies and Enemies

Flynn’s commitment to civil liberties activism never wavered. In 1918, under the auspices of the National Civil Liberties Bureau, the precursor of the ACLU, she founded the Workers Defense Union (WDU). The organization united 170 labor, socialist, and radical left organizations around a mission of providing legal and financial support and securing political prisoner status for activists arrested under the Espionage Act, passed the previous year to quell dissent against Woodrow Wilson’s war “to make the world safe for democracy.”

Many of the WDU’s constituents were immigrants awaiting deportation in deplorable conditions at Leavenworth. Others languished in US jail cells. Arguably the most famous were Italian immigrant anarchists Nicolas Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, for whom Flynn and the WDU campaigned tirelessly, if unsuccessfully, for most of their six-year ordeal.

Suppression of dissent intensified in the post–World War I era. In March 1919, several months before the Palmer Raids began in earnest, the Empire State initiated its own Red Scare with the establishment of the Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Radical Activities.

Commonly known as the Lusk Committee, the panel identified Flynn as a particularly dangerous individual — in no small part because of her work with black activists. She had been an ally of renowned Harlem soapboxer Hubert Harrison since her IWW days. She supported A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen when their socialist newspaper, the Messenger, had its second-class mailing privilege revoked in 1918. And she spoke at a Harlem event to raise funds for victims of the 1919 Elaine Massacre, a violent attempt in Arkansas to suppress labor organizing among black sharecroppers that left five whites and over two hundred blacks dead.

Flynn, while not immune from the shortcomings of the time, refused to marginalize people of color within the labor movement. She knew that, then as now, racism was used as a wedge to prevent the oppressed from making common cause.

In 1920, Flynn was part of the group that founded the American Civil Liberties Union. Throughout its early history, the ACLU was primarily a coalition of liberals and radicals dedicated to protecting the rights of workers and their advocates. With Flynn acting as liaison between the Boston-based anarchist community that supported Sacco and Vanzetti, and liberals in the Bay State and New York, the ACLU endorsed the cause of the two anarchists. Flynn worked closely with ACLU president Roger Baldwin, whom she also knew from her IWW days, until taking a leave of absence from activism in 1926.

Flynn returned to public life ten years later when she joined the Communist Party (CP). The fit between her and the CP at the time was a natural one. The party had recently launched its Popular Front strategy, an antifascist alliance between socialists, liberals, and trade unionists. She had been a sworn enemy of capitalism practically since birth and had been an outspoken antifascist since Mussolini’s ascent to power in 1922.

But Flynn’s membership in the CP also revealed the tenuous nature of alliances between liberals and the Left. Fellow members of the ACLU knew of her CP affiliation when they re-elected her unanimously to the executive board in 1939. The ACLU itself was part of the Popular Front coalition. But the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939 brought a rising tide of anti-Communism that left the organization vulnerable to red-baiting. In a move that left an indelible stain on its reputation, members of the ACLU executive board voted to purge Communists from its ranks. An ardent champion of free speech since her teens, Flynn was now deemed a danger to the US Constitution.

Although the episode stung her bitterly, it did not dim her commitment to civil liberties or to coalition building. Throughout the post–World War II Red Scare and the McCarthy era, Flynn continued to advocate for the rights of Communists and other dissenters. She chaired the defense committee when her comrades were arrested for violating the Smith Act in 1949 and, after being detained and tried herself under the same act, spoke eloquently in her own defense.

We expect to convince you that we are within our established constitutional rights to advocate change and progress, to advocate Socialism, which we are convinced will guarantee to all our people in our great and beautiful country the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Whether we are right is no issue here, and no jury, in this or any other trial, but time alone, will decide. Let none of us forget, especially in this trial in dealing with new ideas and proposals for social change, the wise words of Abraham Lincoln: “This country with its institutions belongs to the people who inhabit it.”

Her pleas fell on deaf ears and at the age of sixty-two, for the first time in her career, Flynn was convicted and sentenced to prison. She spent two years behind bars.

Ten years later, in 1964, Flynn died while visiting the Soviet Union. Her ashes lie near the Haymarket memorial in Chicago’s Waldheim cemetery.

Flynn in the Age of Trump

The life and activism of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn merits wide recognition, especially in the era of Trump.

Her political career shows that demonstrations are most effective when they have a tangible goal, and that organizers must be flexible in adapting tactics to the requirements and constraints of a situation. It shows that all those who take part in mass movements must be ready to face the repressive response of the state, whether it comes through legislation, intimidation, or direct violence.

If Flynn were alive today, she would surely be in the forefront of the struggle against the right-wing populism of the Trump administration. She would be resisting anti–free speech laws coming down the pipeline, and working to organize the unorganized.

For her, campaigns for democratic rights were bound up in the struggle for socialism, cross-racial solidarity was the foundation of any viable class politics, and the fight for liberation, while never over, always found its fullest expression in the streets.

_______________

Mary Anne Trasciatti teaches rhetoric, women’s studies, and labor studies at Hofstra University. She is writing a book on Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s free speech activism.

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to Jacobin

Spread the word