July 31st is Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, the day that marks how long into 2017 an African American woman would have to work in order to be paid the same wages as her white male counterpart was paid last year. Black women are uniquely positioned to be subjected to both a racial pay gap and a gender pay gap. In fact, on average, black women workers are paid only 67 cents on the dollar relative to white non-Hispanic men, even after controlling for education, years of experience, and location.

Why does this wage gap exist for black women?

Pay inequity directly touches the lives of black women in at least three distinct ways. Since few black women are among the top 5 percent of earners in this country, they have experienced the relatively slow wage growth that characterizes growing class inequality along with the vast majority of other Americans. But in addition to this class inequality, they also experience lower pay due to gender and race bias.

In the last 37 years, gender wage gaps have unquestionably narrowed—due in part to men’s wages decreasing—while racial wage gaps have gotten worse. Despite the large gender disadvantage faced by all women, black women were near parity with white women in 1979. However in 2016, white women’s wages grew to 76 percent of white men’s, compared to 67 percent for black women relative to white men—a racial difference of 9 percentage points. The trend is going the wrong way—progress is slowing for black women.

Myth #1: If black women worked harder, they’d get the pay they deserve.

The truth: Black women work more hours than white women. They have increased work hours 18.4 percent since 1979, yet the wage gap relative to white men has grown.

Over the last several decades, both black and white workers have increased their number of annual hours in response to slow wage growth. While men typically work more hours than women, the data reveal that growth in work hours, for both whites and blacks, was heavily driven by the growth of work hours among women. The increase in annual hours is particularly striking for workers in the bottom 40 percent of the wage distribution, where it has been driven almost entirely by women.

Among lower paid workers, the growth in annual hours is larger for black women than for white women and men. This trend is particularly striking for the lowest wage workers. In the bottom fifth, annual hours for black women grew 30.1 percent (from 1,162 hours/year to 1,511 hours/year) between 1979 and 2015 compared to a 27.6 percent increase (from 1,086 hours/year to 1,386 hours/year) for white women and a 3.2 percent increase (from 1,553 hours/year to 1,602 hours/year) for white men.

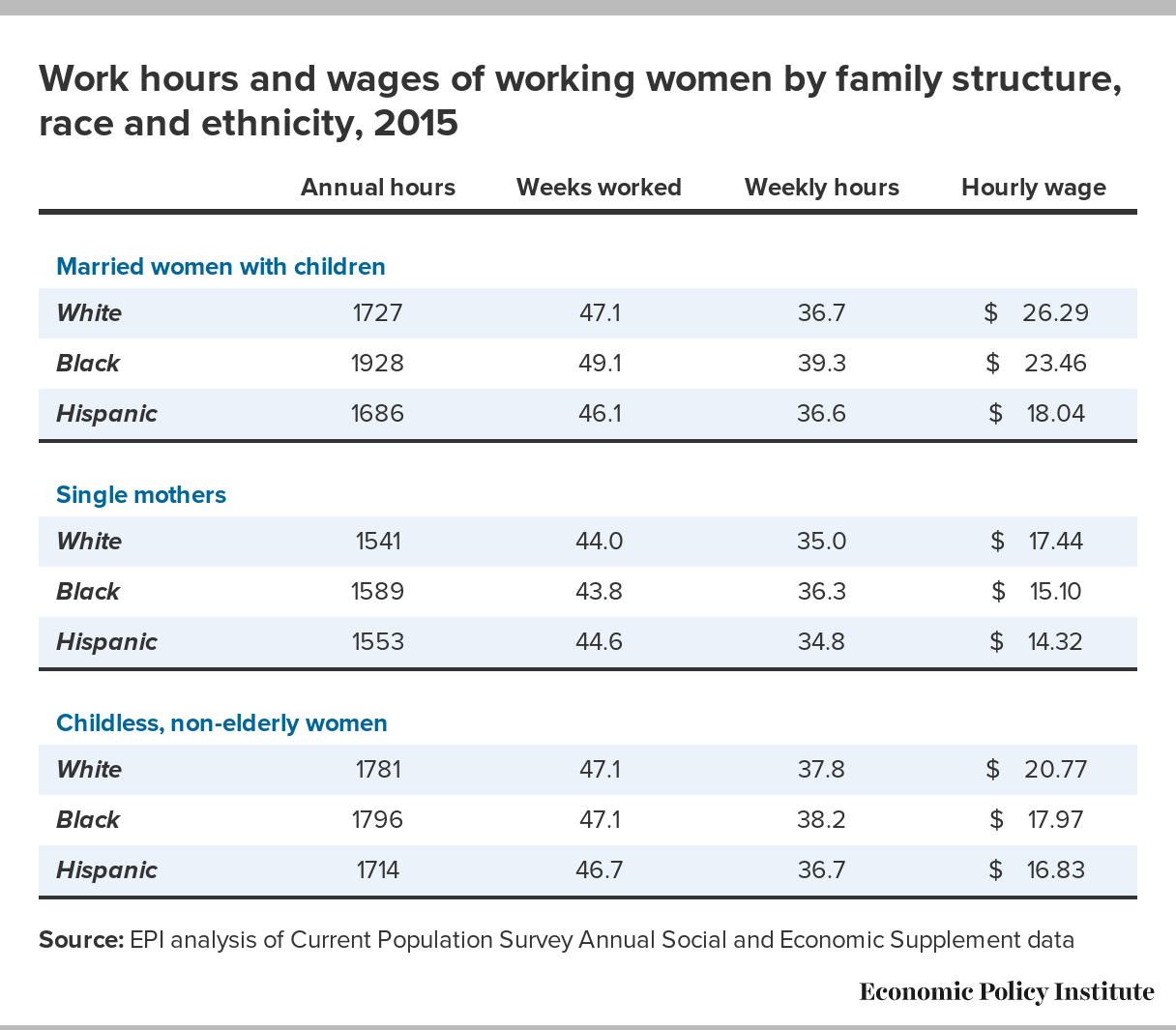

Working moms are significant contributors to this trend—half of all African American female workers are moms, as are 55.3 percent of Hispanic working women and 44.5 percent of white female workers – although women often face a wage penalty when taking time out of the workforce to care for children. While all moms are working more hours per year and contributing more to their households financially, African American working moms are uniquely central to the economic well-being of their families.

Even when faced with the added demands on their time that come with having a family, in 2015, married black women with children worked over 200 hours more per year than married white or Hispanic women with children, and 339 hours more than black single mothers. Married black working moms also worked 132 hours more per year than childless non-elderly black working women.

The data make it clear that there has been no lack of effort on the part of black women workers. Even in the face of persistent racial wage gaps, labor market discrimination, occupational segregation, and other labor market obstacles, black women continue to increase their annual hours and weeks worked per year.

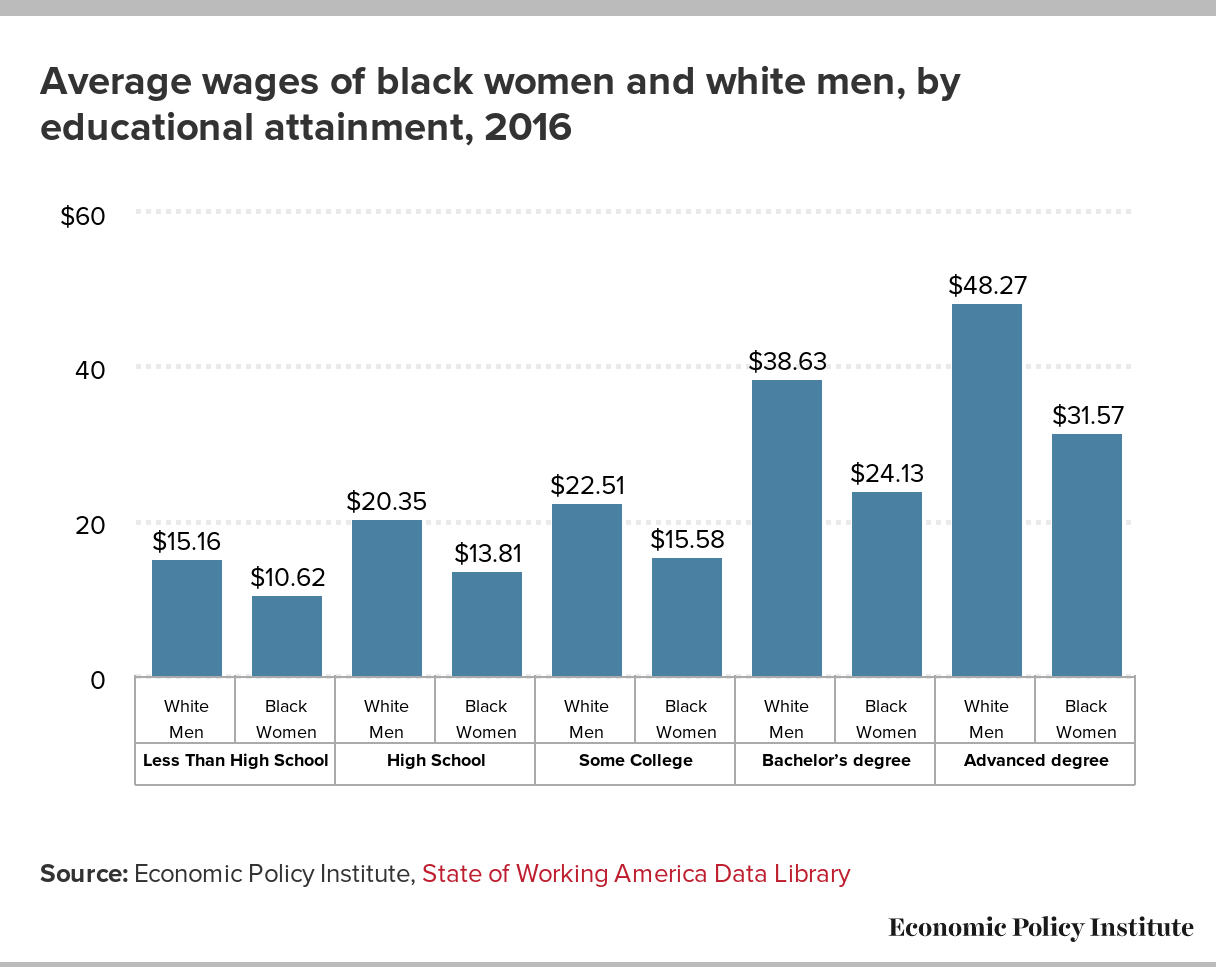

Myth #2: Black women can educate themselves out of the pay gap.

The truth: Two-thirds of black women in the workforce have some postsecondary education, 29.4 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Black women are paid less than white men at every level of education.

The figure below shows average wages for white men and black women in 2016. As black women increase their educational attainment, their pay gap with white men continues to grow. The largest gap, of nearly $17 an hour, occurs for workers with more than a college degree. But even black women with an advanced degree earn less, slightly more than $7 an hour less, than white men who only have a bachelor’s degree.

This, again, in part likely reflects labor market policies that foster more-equal outcomes for workers in the lower tier of the wage distribution. It also may be affected by certain challenges that disproportionately affect women’s ability to secure jobs at the top of the wage distribution, such as earnings penalties for time out of the workforce, excessive work hours, domestic gender roles, and pay and promotion discrimination.

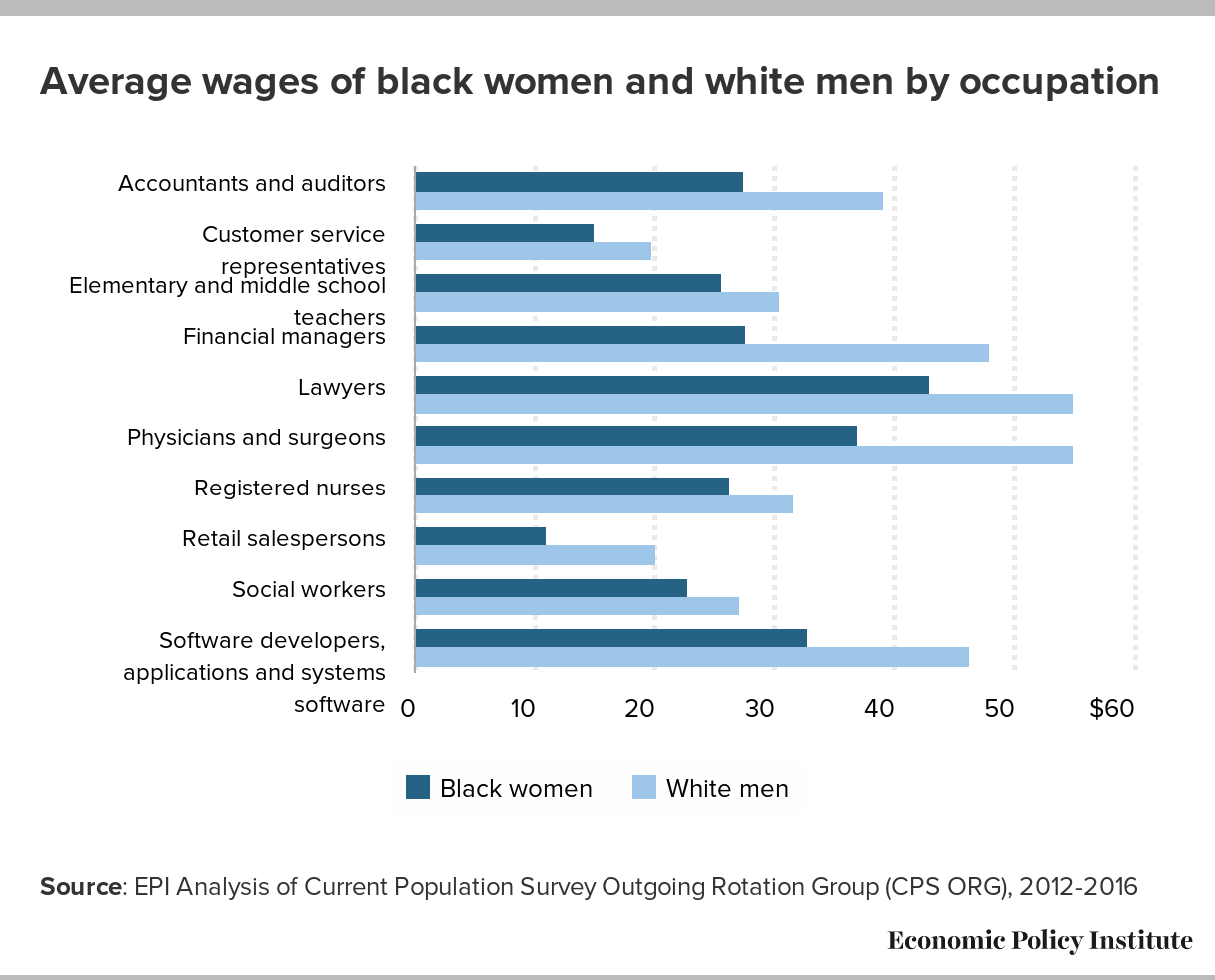

Myth #3: The wage gap is the result of black women choosing careers that pay less.

The truth: In all occupations—both female-dominated and male-dominated—black women earn less than white men.

The table below shows the average wages for black women and white men in a range of occupations. In various industries and occupations across the labor market, black women earn less than white men. Occupational segregation, which pushes black women into jobs mostly populated by other black women, has had an effect on the racial wage gap in recent years. But the racial wage gap is present in jobs dominated by black women and jobs dominated by white men, as shown below. While white male physicians and surgeons earn, on average, $18 per hour more than black women doing the same job, the gap for retail salespersons is also shocking, at more than $9 an hour.

As black women continue to be over-represented in low-wage jobs, policies that lift wages at the bottom will have a significant impact on their wages. An increase of the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2024 would affect more than one in four black women workers.

The data confirm black women are underpaid. The usual explanations of the pay gap perpetuate racial and gender biases and stereotypes of black workers as unmotivated and lazy, but the data tell another story. Regardless of their connection to the labor market, their level of educational attainment, or their occupation, they are paid less than their white male counterparts. The ongoing gender and racial discrimination faced by black women means that seven months into 2017, black women finally have equal pay with what white men earned last year.

______________________________________________________________________

Valerie Rawlston Wilson is director of the Economic Policy Institute’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy (PREE), a nationally recognized source for expert reports and policy analyses on the economic condition of America’s people of color. Prior to joining EPI, Wilson was an economist and vice president of research at the National Urban League Washington Bureau, where she was responsible for planning and directing the bureau’s research agenda. She has written extensively on various issues impacting economic inequality in the United States—including employment and training, income and wealth disparities, access to higher education, and social insurance—and has also appeared in print, television, and radio media. In 2010, through the State Department’s Bureau of International Information Programs, she was selected to deliver the keynote address at an event on Minority Economic Empowerment at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway. In 2011, Wilson served on a National Academies Panel on Measuring and Collecting Pay Information from U.S. Employers by Gender, Race, and National Origin.

Janelle Jones joined the Economic Policy Institute in 2016. She is an economic analyst working on a variety of labor market topics within EPI’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy (PREE) and the Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN). She was previously a research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), where she worked on topics including racial inequality, unemployment, job quality, and unions. Her research has been cited in The New Yorker, The Economist, Harper’s, The Washington Post, The Review of Black Political Economy, and other publications. She also worked as an economist at the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Janelle has served as an AmeriCorps*VISTA volunteer in Sacramento, California, where she worked for a grassroots nonprofit focused on community health issues. She has also served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Peru in the Small Business Development Program focusing on local economic development.

Kayla Blado joined the Economic Policy Institute as a media relations specialist in 2016. She has worked for a variety of workers’ rights organizations, such as Change to Win and Workers’ Independent News. Previously, Kayla produced several radio shows, including a popular morning news magazine on Wisconsin Public Radio. Kayla also served as an AmeriCorps volunteer in rural Wisconsin, where she helped disabled farmers acquire assistive equipment. She currently serves on the board of New Leaders Council-DC, a progressive political training institute for young professionals.

Elise Gould joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, inequality, economic mobility and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition. Gould authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education, Challenge Magazine, and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics, Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives, and International Journal of Health Services. Gould has been quoted by a variety of news sources, including Bloomberg, NPR, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal, and her opinions have appeared on the op-ed pages of USA Today and the Detroit News. She has testified before the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means, Maryland Senate Finance and House Economic Matters committees, the New York City Council, and the District of Columbia Council.

Spread the word